Newport News, Virginia

Newport News is an independent city in the U.S. state of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 180,719.[6] In 2019, the population was estimated to be 179,225,[3] making it the fifth-most populous city in Virginia.

Newport News, Virginia | |

|---|---|

| City of Newport News | |

The downtown Newport News skyline as seen from 26th Street and I-664 overpass in August 2013 | |

Seal | |

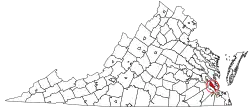

Location in the Commonwealth of Virginia | |

Newport News, Virginia Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 37°4′15″N 76°29′4″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Settled | 1691[1] |

| Incorporated | 1896 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | McKinley L. Price (I) |

| Area | |

| • Independent city | 119.62 sq mi (309.81 km2) |

| • Land | 68.99 sq mi (178.68 km2) |

| • Water | 50.63 sq mi (131.14 km2) 42.4% |

| Elevation | 15 ft (5 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Independent city | 180,719 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 179,225 |

| • Density | 2,597.88/sq mi (1,003.05/km2) |

| • Urban | 1,439,666 |

| • Metro | 1,672,319 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 23601-23609 |

| Area code(s) | 757, 948 (planned) |

| FIPS code | 51-56000[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1497043[5] |

| Website | www.nnva.gov |

Newport News is included in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. It is at the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula, on the northern shore of the James River extending southeast from Skiffe's Creek along many miles of waterfront to the river's mouth at Newport News Point on the harbor of Hampton Roads. The area now known as Newport News was once a part of Warwick County. Warwick County was one of the eight original shires of Virginia, formed by the House of Burgesses in the British Colony of Virginia by order of King Charles I in 1634. The county was largely composed of farms and undeveloped land until almost 250 years later.

In 1881, fifteen years of rapid development began under the leadership of Collis P. Huntington, whose new Peninsula Extension of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway from Richmond opened up means of transportation along the Peninsula and provided a new pathway for the railroad to bring West Virginia bituminous coal to port for coastal shipping and worldwide export. With the new railroad came a terminal and coal piers where the colliers were loaded. Within a few years, Huntington and his associates also built a large shipyard. In 1896, the new incorporated town of Newport News, which had briefly replaced Denbigh as the seat of Warwick County, had a population of 9,000. In 1958, by mutual consent by referendum, Newport News was consolidated with the former Warwick County (itself a separate city from 1952 to 1958), rejoining the two localities to approximately their pre-1896 geographic size. The more widely known name of Newport News was selected as they formed what was then Virginia's third largest independent city in population.

With many residents employed at the expansive Newport News Shipbuilding, the joint U.S. Air Force-U.S. Army installation at Joint Base Langley–Eustis, and other military bases and suppliers, the city's economy is very connected to the military. The location on the harbor and along the James River facilitates a large boating industry which can take advantage of its many miles of waterfront. Newport News also serves as a junction between the rails and the sea with the Newport News Marine Terminals located at the East End of the city. Served by major east–west Interstate Highway 64, it is linked to other cities of Hampton Roads by the circumferential Hampton Roads Beltway, which crosses the harbor on two bridge-tunnels. Part of the Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport is in the city limits.

Etymology

The original area near the mouth of the James River was first referred to as Newportes Newes as early as 1621.[7]

The source of the name "Newport News" is not known with certainty, though it is the oldest English city name in the Americas.[8] Several versions are recorded, and it is the subject of popular speculation locally. Probably the best-known explanation holds that when an early group of Jamestown colonists left to return to England after the Starving Time during the winter of 1609–1610 aboard a ship of Captain Christopher Newport, they encountered another fleet of supply ships under the new Governor Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr in the James River off Mulberry Island with reinforcements of men and supplies. The new governor ordered them to turn around, and return to Jamestown. Under this theory, the community was named for Newport's "good news". Another possibility is that the community may have derived its name from an old English word "news" meaning "new town". At least one source claims that the "New" arose from the original settlement's being rebuilt after a fire.[9]

Another source gave the original name as New Port Newce, named for a person with the name Newce and the town's place as a new seaport. The namesake, Sir William Newce, was an English soldier and originally settled in Ireland. There he had established Newcestown near Bandon, County Cork. He sailed to Virginia with Sir Francis Wyatt in October 1621 and was granted 2,500 acres (1,012 ha) of land. He died two days later. His brother, Capt. Thomas Newce, was given "600 acres at Kequatan, now called Elizabeth Cittie." A partner Daniel Gookin completed founding the settlement.[10]

In his 1897 two-volume work Old Virginia and her Neighbors, American historian John Fiske writes:

... several old maps where the name is given as Newport Ness, being the mariner's way of saying Newport Point.[11]

The fact that the name formerly appeared as "Newport's News" is verified by numerous early documents and maps, and by local tradition. The change to Newport News came about through usage; by 1851 the Post Office Department sanctioned "New Port News" (written as three words) as the name of the first post office. In 1866 it approved the name as "Newport News", the current form.[9]

History

_at_Newport_News_Shipbuilding_on_20_March_1942_(NH_75592).jpg.webp)

European settlement

During the 17th century, shortly after founding of Jamestown, Virginia in 1607, English settlers explored and began settling the areas adjacent to Hampton Roads. In 1610, Sir Thomas Gates "took possession" of a nearby Native American village, which became known as Kecoughtan. At that time, settlers began clearing land along the James River (the navigable part of which was called Hampton Roads) for plantations, including the present area of Newport News.

In 1619, the area of Newport News was included in one of four huge corporations of the Virginia Company of London. It became known as Elizabeth Cittie and extended west all the way to Skiffe's Creek (currently the border between Newport News and James City County). Elizabeth Cittie included all of present-day South Hampton Roads.[12]

By 1634, the English colony of Virginia consisted of a population of approximately 5,000 inhabitants. It was divided into eight shires of Virginia, which were renamed as counties shortly thereafter. The area of Newport News became part of Warwick River Shire, which became Warwick County in 1637. By 1810, the county seat was at Denbigh. For a short time in the mid-19th century, the county seat was moved to Newport News.[13]

Restoration

Newport News was a rural area of plantations and a small fishing village until after the American Civil War. Construction of the railroad and establishment of the great shipyard brought thousands of workers and associated development. It was one of only a few cities in Virginia to be newly established without earlier incorporation as a town. (Virginia has had an independent city political subdivision since 1871.) Walter A. Post served as the city's first mayor.[14]

The area that formed the present-day southern end of Newport News had long been established as an unincorporated town. During Reconstruction, the period after the American Civil War, the new City of Newport News was essentially founded by California merchant Collis P. Huntington. Huntington, one of the Big Four associated with the Central Pacific Railroad, in California, formed the western part of the country's First Transcontinental Railroad. He was recruited by former Confederate General Williams Carter Wickham to become a major investor and guiding light for a southern railroad. He helped complete the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway to the Ohio River in 1873.[15]

Huntington knew the railroad could transport coal eastbound from West Virginia's untapped natural resources. His agents began acquiring land in Warwick County in 1865. In the 1880s, he oversaw extension of the C&O's new Peninsula Subdivision, which extended from the Church Hill Tunnel in Richmond southeast down the peninsula through Williamsburg to Newport News, where the company developed coal piers on the harbor of Hampton Roads.[16]

His next project was to develop Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company, which became the world's largest shipyard. Opened as Chesapeake Dry Dock & Construction Company, the shipbuilding was intended to build boats to transition goods from the rails to the seas. With president Theodore Roosevelt's declaration to create a Great White Fleet, the company entered the warship business by building seven of the first sixteen warships.

1900s

In addition to Collis, other members of the Huntington family played major roles in Newport News. From 1912 to 1914, his nephew, Henry E. Huntington, assumed leadership of the shipyard. Huntington Park, developed after World War I near the northern terminus of the James River Bridge, is named for him.[17]

Collis Huntington's son, Archer M. Huntington and his wife, sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington, developed the Mariners' Museum beginning in 1932. They created a natural park and the community's Mariners' Lake in the process. A major feature of Newport News, the Mariners' Museum has grown to become one of the largest and finest maritime museums in the world.[18]

The city grew in territory through the annexation of parts of Warwick County and also of the town of Kecoughtan in adjoining Elizabeth City County.

In 1958, the citizenry of the cities of Warwick and Newport News voted by referendum to consolidate the two cities, choosing to assume the better-known name of Newport News. The merger created the third largest city by population in Virginia, with a 65 square miles (168 km2) area. The boundaries of the City of Newport News today are essentially the boundaries of the original Warwick River Shire and the traditional one of Warwick County, with the exception of minor border adjustments with neighbors.[19]

The city's original downtown area, on the James River waterfront, changed rapidly from a farm trading town to a new city in the last quarter of the 19th century. Development of the railroad terminal, with its coal piers, other harbor-related facilities, and the shipyard, brought new jobs and workers to the area. Although fashionable housing and businesses developed in downtown, the increase in industry and the development of new suburbs pushed and pulled retail and residential development to the west and north after World War II. Such suburban development was aided by national subsidization of highway construction and was part of a national trend to newer housing.

In July 1989, the United States Navy commissioned the third naval vessel named after the city with the entry of the Los Angeles-class nuclear submarine USS NEWPORT NEWS (SSN-750), built at Newport News Shipbuilding, into active service.

The ship was initially commanded by CDR. Mark B. Keef; the city held a public celebration of the event, which was attended by Vice President of the United States Dan Quayle. In conjunction with this milestone, a song was written by a city native and formally adopted by Newport News City Council in July 1989. The lyrics appear with permission from the author:

(First verse): Harbor of a thousand ships/Forger of a nation's fleet/Gateway to the New World/Where ocean and river meet

(Chorus): Strength wrought from steel/And a people's fortitude/Such is the timeless legacy/Of a place called Newport News

(Second verse): Nestled in a blessed land/Gifted with a special view/Forever home for ev'ry man/With a spirit proud and true

(repeat chorus to fade)

2000s

Despite city efforts at large-scale revitalization, by the beginning of the 21st century the downtown area consisted largely of the coal export facilities, the shipyard, and municipal offices. It is bordered by some harbor-related smaller businesses and lower income housing.[20]

Newport News grew in population from the 1960s through the 1990s. The city began to explore New Urbanism as a way to develop areas midtown. City Center at Oyster Point was developed out of a small portion of the Oyster Point Business Park. It opened in phases from 2003 through 2005. The city invested $82 million of public funding in the project.[21] Closely following Oyster Point, Port Warwick opened as an urban residential community in the new midtown business district. Fifteen hundred people now reside in the Port Warwick area. It includes a 3-acre (1.2 ha) city square where festivals and events take place.[22]

Geography

Newport News is located at 37°4′15″N 76°29′4″W (37.071046, −76.484557). According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 120 square miles (310 km2), of which 69 square miles (180 km2) is land and 51 square miles (130 km2) (42.4%) is water.[23]

The city is located at the Peninsula side of Hampton Roads in the Tidewater region of Virginia, bordering the Atlantic Ocean. The Hampton Roads Metropolitan Statistical Area (officially known as the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC MSA) is the 37th largest in the nation with a 2014 population estimate of 1,716,624. The area includes the Virginia cities of Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Chesapeake, Hampton, Newport News, Poquoson, Portsmouth, Suffolk, Williamsburg, and the counties of Gloucester, Isle of Wight, James City, Mathews, Surry, and York, as well as the North Carolina counties of Currituck and Gates. Newport News serves as one of the business centers on the Peninsula. The city of Norfolk is recognized as the central business district, while the Virginia Beach oceanside resort district and Williamsburg are primarily centers of tourism.

Newport News shares land borders with James City County on the northwest, York County on the north and northeast, and Hampton on the east. Newport News shares water borders with Portsmouth on the southeast and Suffolk on the south across the Hampton Roads Area, and Isle of Wight County on the southwest and west and Surry County on the northwest across the James River.

Cityscape

.jpg.webp)

The city's downtown area was part of the earliest developed area which was initially incorporated as an independent city in 1896. The earlier city portions also included the "East End" or "Southeast" community, which was predominantly African-American, the "North End" and the shipyard and coal piers. The town of Kecoughtan in Elizabeth City County was annexed by Newport News in 1927, extending the city along Hampton Roads from Salter's Creek to Pear Avenue. After World War II, public housing projects and lower income housing were built to improve housing in what came to be known as the East End or "The Bottom" by locals.[14] The city expanded primarily westward where land was available and highways were built. While the shipyard and coal facilities, and other smaller harbor-oriented businesses have remained vibrant, the downtown area went into substantial decline. Crime problems have plagued the nearby lower-income residential areas.

West of the traditional downtown area, another early portion of the city was developed as Huntington Heights. In modern times been called the North End. Developed primarily between 1900 and 1935, North End features a wealth of architectural styles and eclectic vernacular building designs. Extending along west to the James River Bridge approaches, it includes scenic views of the river. A well-preserved community, the North End is an historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register.[24]

The 1958 merger by mutual agreement with the City of Warwick removed the political boundary, which was adjacent to Mercury Boulevard. This major north–south roadway carries U.S. Route 258 between the James River Bridge and the Coliseum-Central area of adjacent Hampton. At the time, the county was mostly rural, although along Warwick Boulevard north of the Mercury Boulevard, Hilton Village was developed during World War I as a planned community. Beyond this point to the west, much of the city takes on a suburban nature. Many neighborhoods have been developed, some around a number of former small towns. Miles of waterfront along the James River, and tributaries such as Deep Creek and Lucas Creek, are occupied by higher-end single family homes. In many sections, wooded land and farms gave way to subdivisions. Even at the northwestern reaches, furthest from the traditional downtown area, some residential development has occurred. Much land has been set aside for natural protection, with recreational and historical considerations. Along with some newer residential areas, major features of the northwestern end include the reservoirs of the Newport News Water System (which include much of the Warwick River), the expansive Newport News Park, a number of public schools, and the military installations of Fort Eustis and a small portion of the Naval Weapons Station Yorktown.

At the extreme northwestern edge adjacent to Skiffe's Creek and the border with James City County is the Lee Hall community, which retains historical features including the former Chesapeake and Ohio Railway station which served tens of thousands of soldiers based at what became nearby Fort Eustis during World War I and World War II. The larger-than-normal rural two-story frame depot is highly valued by rail fans and rail preservationists.[25]

In downtown Newport News, the Victory Arch, built to commemorate the Great War, sits on the downtown waterfront. The "Eternal Flame" under the arch was cast by Womack Foundry, Inc. in the 1960s. It was hand crafted by the Foundry's founder and president, Ernest D. Womack. The downtown area has a number of landmarks and architecturally interesting buildings, which for some time were mostly abandoned in favor of building new areas in the northwest areas of the city (a strategy aided by tax incentives in the postwar years).

City leaders are working to bring new life into this area, by renovating and building new homes and attracting businesses. The completion of Interstate 664 restored the area to access and through traffic which had been largely rerouted with the completion of the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel connecting neighboring Hampton with the Southside in 1958 and discontinuance of the Newport News-Norfolk ferry service at that time. The larger capacity Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel and the rebuilt James River Bridge each restored some accessibility and through traffic to the downtown area.[26][27]

Much of the newer commercial development has been along the Warwick Boulevard and Jefferson Avenue corridors, with newer planned industrial, commercial, and mixed development such as Oyster Point, Kiln Creek and the City Center. While the downtown area had long been the area of the city that offered the traditional urban layout, the city has supported a number of New Urbanism projects. One is Port Warwick, named after the fictional city in William Styron's novel, Lie Down in Darkness. Port Warwick includes housing for a broad variety of citizens, from retired persons to off-campus housing for Christopher Newport University students. Also included are several high-end restaurants and upscale shopping.[28]

City Center at Oyster Point, located near Port Warwick, has been touted as the new "downtown" because of its new geographic centrality on the Virginia Peninsula, its proximity to the retail/business nucleus of the city, etc. Locally, it is often called simply "City Center".[29] Nearby, the Virginia Living Museum recently completed a $22.6 million expansion plan.[30]

Newport News is also home to a small Korean ethnic enclave on Warwick Boulevard near the Denbigh neighborhood on the northern end of the city. Although it lacks the density and character of larger, more established enclaves, it has been referred to as "Little Seoul"—being the commercial center for the Hampton Roads Korean community.[31]

Neighborhoods

Newport News has many distinctive communities and neighborhoods within its boundaries, including Brandon Heights, Brentwood, City Center, Colony Pines, Christopher Shores-Stuart Gardens, Denbigh, Glendale, East End, Hidenwood, Hilton Village, Hunter's Glenn, Beaconsdale, Ivy Farms, North End Huntington Heights (Historic District – roughly from 50th to 75th street, along the James River), Jefferson Avenue Park, Kiln Creek, Lee Hall, Menchville, Maxwell Gardens, Morrison (also known as Harpersville and Gum Grove), Newmarket Village, Newsome Park, Oyster Point, Parkview, old North Newport News (Center Ave. area), Port Warwick, Richneck, Riverside, Shore Park, Summerlake, Village Green, Windsor Great Park and Warwick. Some of these neighborhoods are located in the former City of Warwick and Warwick County.

Climate

Newport News is located in the humid subtropical climate zone, with cool to mild winters, and hot, humid summers. Due to the inland location, throughout the year, highs are 2 to 3 °F (1.1 to 1.7 °C) warmer and lows 1 to 2 °F (0.6 to 1.1 °C) cooler than areas to the southeast. Snowfall averages 5.8 inches (15 cm) per season, and the summer months tend to be slightly wetter. The geographic location of the city, with respect to the principal storm tracks, favours fair weather, as it is south of the average path of storms originating in the higher latitudes, and north of the usual tracks of hurricanes and other major tropical storms.[32]

| Climate data for Newport News, Virginia (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 49.5 (9.7) |

52.9 (11.6) |

60.7 (15.9) |

71.1 (21.7) |

78.5 (25.8) |

86.2 (30.1) |

89.6 (32.0) |

87.4 (30.8) |

82.2 (27.9) |

72.5 (22.5) |

63.3 (17.4) |

53.4 (11.9) |

70.6 (21.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 31.8 (−0.1) |

32.6 (0.3) |

39.5 (4.2) |

47.8 (8.8) |

57.0 (13.9) |

66.3 (19.1) |

70.3 (21.3) |

68.8 (20.4) |

62.7 (17.1) |

51.7 (10.9) |

43.0 (6.1) |

34.6 (1.4) |

50.5 (10.3) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.33 (85) |

3.01 (76) |

3.44 (87) |

3.33 (85) |

3.74 (95) |

3.81 (97) |

4.71 (120) |

5.35 (136) |

4.79 (122) |

3.47 (88) |

3.08 (78) |

3.38 (86) |

45.44 (1,155) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 2.4 (6.1) |

2.1 (5.3) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.0 (2.5) |

5.8 (14.66) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.4 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 10.6 | 9.9 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 116.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 3.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 170.5 | 178.0 | 229.4 | 252.0 | 272.8 | 279.0 | 279.0 | 260.4 | 231.0 | 207.7 | 177.0 | 161.2 | 2,698 |

| Source: NOAA (temperature and total precipitation normals at Newport News Int'l, all others at Norfolk Int'l),[33] HKO (sun only 1961–1990)[34] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 1,234 | — | |

| 1900 | 19,635 | 1,491.2% | |

| 1910 | 20,205 | 2.9% | |

| 1920 | 35,596 | 76.2% | |

| 1930 | 34,417 | −3.3% | |

| 1940 | 37,067 | 7.7% | |

| 1950 | 42,358 | 14.3% | |

| 1960 | 113,788 | 168.6% | |

| 1970 | 138,177 | 21.4% | |

| 1980 | 144,903 | 4.9% | |

| 1990 | 170,045 | 17.4% | |

| 2000 | 180,150 | 5.9% | |

| 2010 | 180,719 | 0.3% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 179,225 | [3] | −0.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[35] 1790–1960[36] 1900–1990[37] 1990–2000[38] 2018 Estimate[39] | |||

.png.webp)

As of the census[40] of 2010, there were 180,719 people, 69,686 households, and 46,341 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,637.9 people per square mile (1,018.5/km2). There were 74,117 housing units at an average density of 1,085.3 per square mile (419.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 49.0% White, 40.7% African American, 0.5% Native American, 2.7% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 2.7% from other races, and 4.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.5% of the population (2.5% Puerto Rican, 2.5% Mexican, 0.4% Cuban, 0.3% Panamanian, 0.2% Dominican, 0.2% Guatemalan, 0.2% Honduran).

There were 69,686 households, out of which 35.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.6% were married couples living together, 17.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.5% were non-families. 27.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.50 and the average family size was 3.04.

The age distribution is: 27.5% under the age of 18, 11.5% from 18 to 24, 32.2% from 25 to 44, 18.8% from 45 to 64, and 10.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $36,597, and the median income for a family was $42,520. Males had a median income of $31,275 versus $22,310 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,843. About 11.3% of families and 13.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.6% of those under age 18 and 9.8% of those age 65 or over.

Crime

| Crime (per 100,000 people) | Newport News, Virginia (2007) | National average |

|---|---|---|

| Murder | 15.8 | 5.6 |

| Rape | 51.3 | 32.2 |

| Robbery | 288.9 | 195.4 |

| Assault | 336.2 | 340.1 |

| Burglary | 892.1 | 814.5 |

| Automobile theft | 377.4 | 526.5 |

Newport News experienced 20 murders giving the city a murder rate of 10.8 per 100,000 people in 2005. In 2006, there were 19 murders giving the city a rate of 10.5 per 100,000 people. In 2007 the city had 28 murders with a rate of 15.8 per 100,000 people.

The total crime index rate for Newport News is 434.7; the United States average is 320.9.[41] According to the Congressional Quarterly Press' "2008 City Crime Rankings: Crime in Metropolitan America," Newport News ranked as the 119th most dangerous city larger than 75,000 inhabitants.[42] The neighborhood with the highest crime rates in Newport News is the East End.

Economy

Among the city's major industries are shipbuilding, military, and aerospace. Newport News Shipbuilding, owned by Huntington Ingalls Industries,[43] and the large coal piers supplied by railroad giant CSX Transportation, the modern Fortune 500 successor to the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O). Miles of the waterfront can be seen by automobiles crossing the James River Bridge and Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel, which is a portion of the circumferential Hampton Roads Beltway, linking the city with each of the other major cities of Hampton Roads via Interstate 664 and Interstate 64. Many U.S. defensive industry suppliers are based in Newport News, and these and nearby military bases employ many residents, in addition to those working at the shipyard and in other harbor-related vocations.

Newport News plays a role in the maritime industry. At the end of CSX railroad tracks lies the Newport News Marine Terminal. Covering 140 acres (0.57 km2), the Terminal has heavy-lift cranes, warehouse capabilities, and container cranes.[44]

Newport News' location next to Hampton Roads along with its rail network has provided advantages for the city. The city houses two industrial parks which enabled manufacturing and distribution to take root in the city. As technology-oriented companies flourished in the 1990s, Newport News became a regional center for technology companies.[45]

Additional companies headquartered out of Newport News include Ferguson Enterprises and L-3 Flight International Aviation.[46][47]

Newport News Shipbuilding serves as the city's largest employer with over 24,000 employees. Fort Eustis employs over 10,000, making it the second largest employer in the city. Newport News School System creates over 5000 jobs and acts as the city's third largest employer.[48]

Established during World War I at historic Mulberry Island, the base at Fort Eustis in modern times houses the United States Army Training and Doctrine Command and other activities.[49] In adjacent localities, other U.S. military facilities include Langley Air Force Base, Naval Weapons Station Yorktown, Camp Peary, and the now-deactivated Fort Monroe. Other installations are located across the James River in South Hampton Roads, including the world's largest naval base, Naval Station Norfolk.[50][51]

Research and education play a role in the city's economy. The Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility (TJNAF) is housed in Newport News. TJNAF employs over 675 people and more than 2,000 scientists from around the world conduct research using the facility. Formerly named the Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility (CEBAF), its stated mission is "to provide forefront scientific facilities, opportunities and leadership essential for discovering the fundamental structure of nuclear matter; to partner in industry to apply its advanced technology; and to serve the nation and its communities through education and public outreach."[52]

Culture

People who have grown up in the Hampton Roads area have a unique Tidewater accent which is found among natives of Eastern Virginia and Maryland. Vowels have a longer pronunciation than in most accents.[53]

Near the city's western end, a historic C&O railroad station, as well as American Civil War battle sites near historic Lee Hall along U.S. Route 60 and several 19th century plantations have all been protected. Many are located along the roads leading to Yorktown and Williamsburg, where many sites of the Historic Triangle are of both American Revolutionary War and Civil War significance. The first modern duel of ironclad warships, the Battle of Hampton Roads, took place not far off Newport News Point in 1862.[54]

Recovered artifacts from USS Monitor are displayed at the Mariners' Museum, one of the more notable museums of its type in the world. The museum's collection totals approximately 32,000 artifacts, international in scope, which include ship models, scrimshaw, maritime paintings, decorative arts, figureheads and engines. The museum also owns and maintains a 550-acre park on which is located the Noland Trail, and the 167-acre Mariners' Lake.[55]

The Virginia War Museum covers American military history. The museum's collection includes, weapons, vehicles, artifacts, uniforms and posters from various periods of American history. Highlights of the Museum's collection include a section of the Berlin Wall and the outer wall from Dachau Concentration Camp.[56]

The Peninsula Fine Arts Center contains a rotating gallery of art exhibits. The Center also maintains a permanent "Hands on For Kids" gallery designed for children and families to interact in what the Center describes as "a fun, educational environment that encourages participation with art materials and concepts."[57]

The U.S. Army Transportation Museum is a United States Army museum of vehicles and other U.S. Army transportation-related equipment and memorabilia. Located on the grounds of Fort Eustis, The museum reflects the history of the Army, especially of the United States Army Transportation Corps, and includes close to 100 military vehicles such as land vehicles, watercraft and rolling stock, including stock from the Fort Eustis Military Railroad. It is officially dedicated to General Frank S. Besson, Jr., who was the first four-star general to lead the transportation command,[58] and extends over 6 acres (24,000 m2) of land, air and sea vehicles and indoor exhibits. The exhibits cover transportation and its role in US Army operations, including topic areas from the American Revolutionary War through operations in Afghanistan.[59]

The Ferguson Center for the Arts is a theater and concert hall on the campus of Christopher Newport University. The complex fully opened in September 2005 and contains three distinct, separate concert halls: the Concert Hall, the Music and Theatre Hall, and the Studio Theatre.[60]

The Port Warwick area hosts the annual Port Warwick Art and Sculpture Festival where art vendors gather in Styron Square to show and sell their art. Judges have the chance to name art work best of the Festival.[61]

The Virginia Living Museum is an outdoor living museum combining aspects of a native wildlife park, science museum, aquarium, botanical preserve, and planetarium.[62]

Sports

Newport News has been the home to sports franchises, including the semi-pro football Mason Dixon League's Peninsula Pirates and Peninsula Poseidons and now the Virginia Crusaders.[63] The Christopher Newport University Captains field fourteen sports and compete in the Capital Athletic Conference in Division III of the NCAA.[64]

High school sports (especially football) play a large role in the city's culture. Sporting stars such as Michael Vick, Mike Tomlin, Al Toon, Aaron Brooks, and Antoine Bethea are from Newport News. The city's stadium, John B. Todd Stadium, houses five high schools' worth of football games usually spread over Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights. The stadium also holds the schools' track and field meets.[65][66]

Additional sports options can be found just outside Newport News. On the collegiate level, the College of William and Mary, Hampton University, Norfolk State University and Old Dominion University offer NCAA Division I athletics. Virginia Wesleyan College also provides sports at the NCAA Division III level. The Peninsula Pilots play just outside the city limits at War Memorial Stadium in Hampton. The Pilots play in the Coastal Plain League, a summer baseball league. In Norfolk, the Norfolk Tides of the International League and the Norfolk Admirals of the American Hockey League. In Virginia Beach, the Hampton Roads Piranhas field men's and women's professional soccer teams.[67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74] The Atlantic 10 Conference has been headquartered in Newport News since 2009.

Parks and recreation

Newport News Parks is responsible for the maintenance of 32 city parks. The smallest is less than half an acre (2,000 m2). The largest, Newport News Park, is 7,711 acres (31.21 km2).[75] They are scattered throughout the city, from Endview Plantation in the northern end of the city to King-Lincoln Park in the southern end near the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel. The parks offer services to visitors, ranging from traditional park services like camping and fishing to activities like archery and disc golf.[76]

Newport News Park is in the northern part of the city. The city's golf course lies in the park along with camping and outdoor activities. There are over 30 miles (48 km) of trails in the Newport News Park complex. It has a 5.3 miles (8.5 km) multi-use bike path. The park offers bicycle and helmet rental, and requires helmet use by children under 14. Newport News Park offers an archery range, disc golf course, and an "aeromodel flying field" for remote-controlled aircraft, complete with a 400 ft (120 m) runway.[77]

The city supplies two public boat ramps for its citizens: Denbigh Park Boat Ramp and Hilton Pier/Ravine.

Denbigh Park allows access into the Warwick River, a tributary of the James River. Denbigh Park also offers a small fishing pier. Hilton Pier offers a small beach in addition to a ravine. Croaker and trout are the fish primarily caught during the summer months and the pier is accessible to visitors in wheelchairs.[78][79]

Media

The City of Newport News operates two local government PEG Channels, Newport News Television (NNTV) and NNTV2. NNTV airs on cable channels Cox 48 & Verizon 19 while NNTV2 is on Cox 46 & Verizon 18. NNTV also operates a YouTube channel of their programming.[80] Residents of Newport News can find programs highlighting local events and various things to do around the city. NNTV airs the City Council Meetings and Planning Commission Meetings live for the public to view while NNTV2 is a bulletin board channel that displays slides for various city events and essential information for residents. NNTV also produces the local Crimeline reports with officers from the Newport News Police Department.

Newport News is also served by several television stations. The Hampton Roads designated market area (DMA) is the 43rd largest in the U.S. with 712,790 homes (0.64% of the total U.S.).[81] The major network television affiliates are WTKR-TV 3 (CBS), WAVY 10 (NBC), WVEC-TV 13 (ABC), WGNT 27 (CW), WTVZ 33 (MyNetworkTV), WVBT 43 (Fox), and WPXV 49 (ION Television) and The Public Broadcasting Service station is WHRO-TV 15.

Newport News's daily newspaper is the Daily Press. Other papers include the Port Folio Weekly, the New Journal and Guide, the Hampton Roads Business Journal, and the James River Journal.

Christopher Newport University publishes its own newspaper, The Captain's Log.[82] Hampton Roads Magazine serves as a bi-monthly regional magazine for Newport News and the Hampton Roads area.[83] Hampton Roads Times serves as an online magazine for all the Hampton Roads cities and counties. Newport News is served by a variety of radio stations on the AM and FM dials, with towers located around the Hampton Roads area.[84]

Government

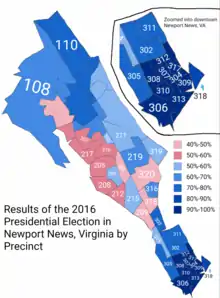

Prior to 1956, Newport News voted in line with a Solid South county except for 1928 when anti-Catholic voting boosted Herbert Hoover to a victory in the county & statewide. From 1956 to 2004, it became a swing county, but became increasingly Democratic towards the end of that stretch. From 2008 on, it has become solidly Democratic thanks in a part to its urban nature & large African American minority. In each presidential election from 2008 on, Democratic candidates have won at least 60% of the county's vote while no Republican candidate has cracked 40%.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 32.5% 26,377 | 65.4% 53,099 | 2.1% 1,727 |

| 2016 | 33.7% 25,468 | 60.3% 45,618 | 6.0% 4,551 |

| 2012 | 34.3% 27,230 | 64.3% 51,100 | 1.4% 1,114 |

| 2008 | 35.3% 28,667 | 63.9% 51,972 | 0.8% 656 |

| 2004 | 47.4% 32,208 | 52.0% 35,319 | 0.6% 425 |

| 2000 | 46.7% 27,006 | 51.5% 29,779 | 1.8% 1,040 |

| 1996 | 42.5% 23,072 | 51.0% 27,678 | 6.5% 3,538 |

| 1992 | 43.8% 26,779 | 42.1% 25,743 | 14.0% 8,569 |

| 1988 | 59.9% 32,570 | 39.4% 21,413 | 0.8% 412 |

| 1984 | 60.4% 33,614 | 39.2% 21,834 | 0.5% 250 |

| 1980 | 47.7% 22,423 | 47.0% 22,066 | 5.3% 2,493 |

| 1976 | 47.0% 20,914 | 51.8% 23,058 | 1.2% 520 |

| 1972 | 67.4% 27,169 | 30.4% 12,233 | 2.3% 910 |

| 1968 | 34.5% 12,774 | 36.1% 13,370 | 29.5% 10,925 |

| 1964 | 40.9% 10,584 | 59.1% 15,296 | 0.1% 14 |

| 1960 | 53.6% 10,098 | 46.0% 8,678 | 0.4% 79 |

| 1956 | 53.3% 3,779 | 43.3% 3,069 | 3.5% 247 |

| 1952 | 40.5% 2,769 | 59.2% 4,051 | 0.3% 23 |

| 1948 | 27.7% 1,453 | 65.3% 3,420 | 7.0% 366 |

| 1944 | 23.3% 1,237 | 76.3% 4,051 | 0.4% 21 |

| 1940 | 18.0% 863 | 81.4% 3,907 | 0.6% 29 |

| 1936 | 18.5% 919 | 81.0% 4,021 | 0.4% 22 |

| 1932 | 35.2% 1,515 | 62.8% 2,703 | 2.0% 86 |

| 1928 | 61.5% 3,118 | 38.5% 1,951 | |

| 1924 | 33.0% 917 | 56.6% 1,574 | 10.5% 292 |

| 1920 | 45.3% 1,450 | 53.2% 1,703 | 1.6% 50 |

| 1916 | 31.7% 465 | 64.1% 939 | 4.2% 61 |

| 1912 | 7.5% 100 | 70.6% 938 | 21.9% 291 |

| 1908 | 37.8% 498 | 59.9% 788 | 2.3% 30 |

| 1904 | 29.4% 335 | 65.2% 744 | 5.4% 62 |

| 1900 | 36.4% 1,108 | 62.2% 1,896 | 1.4% 43 |

| 1896 | 53.8% 815 | 44.6% 676 | 1.7% 25 |

| 1892 | 25.2% 1,542 | 73.2% 4,479 | 1.6% 98 |

| 1888 | 54.8% 3,198 | 44.8% 2,613 | 0.4% 25 |

.jpg.webp)

Newport News is an independent city with services that counties and cities in Virginia provide, such as a sheriff, social services, and a court system.

Newport News operates under a council-manager form of government, which consists of a city council with representatives from three districts serving in a legislative and oversight capacity, as well as a popularly elected, at-large mayor. The city manager serves as head of the executive branch and supervises all city departments and executing policies adopted by the council. Citizens in the three wards elect two council representatives each to serve a four-year term. The city council meets at City Hall twice a month and, as of April 2017, consisted of Mayor McKinley L. Price, Vice Mayor Tina L. Vick, Herbert H. Bateman Jr., Sharon P. Scott, Dr. Patricia "Pat" Woodbury, Saundra Nelson Cherry, D. Min., and Marcellus L. Harris III.[87] The city manager is Cindy Rohlf.

Newport News has a federal courthouse for the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. A new courthouse will be constructed in the future.[88] Additionally, Newport News has its own General District and Circuit Courts which convene downtown.[89] The city is in the Virginia's 3rd congressional district, served by U.S. Representative Robert C. Scott.

Education

The main provider of primary and secondary education in the city is Newport News Public Schools. The school system includes many elementary schools, six middle schools, and the high schools, Denbigh High School, Heritage High School, Menchville High School, Warwick High School, An Achievable Dream Middle/High School, and Woodside High School. All middle, high schools, and elementary schools are fully accredited. Dutrow Elementary is an example of an elementary school that offers a Talented And Gifted program for fifth graders, or rising sixth graders. Crittenden Middle School offers a STEM magnet program to students throughout the district, preparing them for careers in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math. Warwick High School is widely known for its IB program to prepare students at all grade levels for college course levels of thinking.[90]

Several private schools are located in the area, including Denbigh Baptist Christian School, Hampton Roads Academy, Peninsula Catholic High School, Trinity Lutheran School, and Warwick River Christian School.

The city contains Christopher Newport University, a public university. Other nearby public universities include Old Dominion University, Norfolk State University and The College of William and Mary. Hampton University, a private university, also sits a few miles from the city limits. Newport News Shipbuilding operates The Apprentice School, a vocational school teaching various shipyard and related trades.[91]

Thomas Nelson Community College serves as the community college. Located in neighboring Hampton and in nearby Williamsburg, Thomas Nelson offers college and career training programs. Most institutions in the Hampton Roads areas are home to a variety of students but commuter students make up a large portion.[92][93][94][95][96][97]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Newport News has an elaborate transportation network, including interstate and state highways, bridges and a bridge-tunnel, freight and passenger railroad service, local transit bus and intercity bus service, and a commercial airport. There are miles of waterfront docks and port facilities.

Newport News is served by three airports. Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport, in Newport News; Norfolk International Airport, in Norfolk; and Richmond International Airport all of which cater to passengers from Hampton Roads.

The primary airport for the Virginia Peninsula is the Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport. As of 2011, it was experiencing a 5th year of record, double-digit growth, making it one of the fastest growing airports in the country. In January 2006, the airport reported having served 1,058,839 passengers. On February 4, 2010, the airport announced a new airline, Frontier Airlines, with direct flights to Denver, Colorado. It is also undergoing a $23 million expansion project. In 2012, Newport News became home to its own airline, PeoplExpress, which launched with headquarters at the Newport News/Williamsburg airport. Its inaugural first flights took place June 30, 2014 and now includes more than seven destinations. (IATA: PHF, ICAO: KPHF, FAA LID: PHF),[98]

Norfolk International Airport (IATA: ORF, ICAO: KORF, FAA LID: ORF) also serves the region. The airport is near the Chesapeake Bay, along the city limits of Norfolk and Virginia Beach.[99] Seven airlines provide nonstop services to 25 destinations. ORF had 3,703,664 passengers take off or land at its facility and 68,778,934 pounds of cargo were processed through its facilities.[100] The Chesapeake Regional Airport provides general aviation services and is on the other side of the Hampton Roads Harbor.[101]

Amtrak serves the city with four trains a day.[102] The line runs west along the Virginia Peninsula to Richmond and points beyond. Connecting buses are available to Norfolk and Virginia Beach. A high-speed rail connection at Richmond to the Northeast Corridor and the Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor is under study.[103][104]

Intercity bus service is provided by Greyhound Lines (Carolina Trailways). The bus station is on Warwick Boulevard in the Denbigh area.[105] Transportation in the city, as well as with other major cities of Hampton Roads is served by a regional bus service, Hampton Roads Transit.[106] A connecting service for local routes serving Williamsburg, James City County, and upper York County is operated by Williamsburg Area Transit Authority at Lee Hall.[107]

Utilities

The Newport News Waterworks was begun as a project of Collis P. Huntington as part of the development of the lower peninsula with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, the coal piers on the harbor of Hampton Roads, and massive shipyard which were the major sources of industrial growth which helped found Newport News as a new independent city in 1896. It included initially an impoundment of the Warwick River in western Warwick County. Later expansions included more reservoirs, including one at Skiffe's Creek and another at Walkers Dam on the Chickahominy River.[108]

A regional water provider, in modern times it is owned and operated by the City of Newport News, and serves over 400,000 people in the cities of Hampton, Newport News, Poquoson, and portions of York County and James City County.[109]

The city provides wastewater services for residents and transports wastewater to the regional Hampton Roads Sanitation District treatment plants.[110]

Sister cities

Newport News has three sister cities:[111]

Neyagawa, Osaka, Japan

Neyagawa, Osaka, Japan Taizhou, Jiangsu, China

Taizhou, Jiangsu, China Greifswald, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany

Greifswald, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany

See also

- List of people from Hampton Roads

- List of Mayors of Newport News, Virginia

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Newport News, Virginia

- Newport News Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism

- Newport News Sheriff's Office

- Warwick County, Virginia (defunct)

References

- Fox, William A. (2010). Images of America: Downtown Newport News. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7385-8581-9. Retrieved November 3, 2018 – via Google Books.

Newport News was first settled in 1691, but was little more than farms until the late 1880s.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- Newport News Trivia and Fun Facts Archived April 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, newport-news.org; accessed June 21, 2009.

- Fox, William A. (2010). Images of America: Downtown Newport News. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7385-8581-9. Retrieved November 3, 2018 – via Google Books.

Newport News is the oldest English place name of any city in the New World.

- "Why Does Newport News Have Such an Odd Name?", The Mariner's Museum website; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "History of Newport News", William & Mary Quarterly, 1901, scanned on Rootsweb.com; accessed April 3, 2008.

- Fiske Old Virginia and Her Neighbors – footnote (page 92)

- The Virginia Company of London, 1606–1624, by Wesley Frank Craven, Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1957; ISBN 0-8063-4555-1

- "Old Warwick County Courthouse", Discover Our Town. Accessed April 25, 2008.

- "Newport News History Timeline". Newport News Public Library System. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- "Collis Huntington", University of Virginia Library website; accessed July 24, 2015.

- Chesapeake and Ohio Historical Society; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "History" Archived December 16, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Northrop Grumman Newport News Shipbuilding. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- Archer M. Huntington (1870–1955) Archived June 25, 2004, at Archive.today. Retrieved July 21, 2005

- Scott, Thomas M. "Metropolitan Governmental Reorganization Proposals", The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Jun. 1968), pp. 252–261 doi:10.2307/446305.

- "Brownfields Supplemental Assistance" Archived March 1, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency website, May 2002.

- Editorial: "Changing Place" Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Daily Press (Newport News, VA). June 5, 2005, accessed May 9, 2008.

- About Port Warwick Archived May 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, PortWarwick.com; accessed May 9, 2008.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Huntington Heights on the Hampton Roads history and penny postcard tour; accessed April 3, 2008.

- Lee Hall Depot webpage, leehalldepot.org; accessed April 3, 2008.

- I-664 Roads to the Future; accessed April 3, 2008

- "2005 Virginia Department of Transportation Jurisdiction Report – Daily Traffic Volume Estimates – Isle of Wight County" (PDF). (219 KB) Accessed April 3, 2008.

- Port Warwick webpage, portwarwick.com; accessed April 3, 2008.

- City Center at Oyster Point, citycenteratoysterpoint.com; accessed April 3, 2008.

- Erickson, Mark St. John (May 5, 2016). "Virginia Living Museum timeline". dailypress.com. Daily Press. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- Vegh, Steven G. (November 14, 2009). "A little 'Seoul' on Warwick Boulevard". HamptonRoads.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Information from NOAA, wpc.ncep.noaa.gov; accessed July 24, 2015.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- "Climatological Normals of Norfolk". Hong Kong Observatory. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- "Newport News, Virginia (VA) profile: population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, news, sex offenders". www.city-data.com.

- CQ Press: City Crime Rankings 2008 Archived June 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Overview Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Northrop Grumman Newport News Shipbuilding. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- Newport News Marine Terminal Archived December 12, 2005, at Archive.today Virginia Port Authority. Accessed April 2, 2008

- Economy – Economic Base Archived October 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Newport News Economic Development Authority. Accessed April 30, 2008.

- About Us Ferguson Enterprises Accessed April 3, 2008.

- L-3 Flight International Aviation Archived April 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine L-3 Accessed April 3, 2008

- Economy – Largest Employers Archived March 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Newport News City Economic Development Authority. Accessed April 30, 2008.

- Fort Eustis Home Page Archived April 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine U.S. Army. Accessed April 4, 2008.

- GlobalSecurity.org: Langley AFB Accessed April 4, 2008.

- NWS Yorktown Archived March 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine U.S. Navy. Accessed April 4, 2008

- Ware, Linda (September 26, 2005). "Jefferson Lab scientists set to test germ-killing fabrics". Press Release PR-JLAB-05-4. Argonne, IL: Lightsources.org. Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2005.

- Citation Needed

-

- Milton, Keith. "Duel at Hampton Roads." Military Heritage. December 2001. Volume 3, No. 3: 38–45, 97 (Ironclads C.S.A. Virginia (also known as Merrimack) versus the Union Monitor of the Civil War).

- The Mariners' Museum "Museum History"

- Exhibits Archived February 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Virginia War Museum. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- Hands on For Kids Gallery Archived October 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Peninsula Fine Arts Center. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- "Frank Besson page". U.S. Army Transportation Museum site. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "main page". U.S. Army Transportation Museum site. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- Our Mission Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine The Ferguson Center of the Arts; accessed April 3, 2008.

- About Port Warwick Art and Sculpture Festival Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Port Warwick Art and Sculpture Festival; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "About Us". The Virginia Living Museum. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved July 1, 2008.

- About Us Archived February 21, 2009, at Archive.today Mason Dixon Football League

- CNU Athletics Christopher Newport University; accessed February 26, 2017.

- Todd Stadium 2005 Schedule Archived April 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Newport News Public Schools. Accessed April 17, 2008.

- Athletics, Newport News Public Schools Archived July 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, sbo.nn.k12.va.us; accessed April 17, 2008.

- "Norfolk Admirals". Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "Norfolk Tides". Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "ODU Monarchs". Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "NSU Spartans". Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "VWC Marlins". Archived from the original on January 25, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "W&M Tribe". Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- "Peninsula Pilots". Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- "Hampton Roads Piranhas". Archived from the original on August 19, 2000. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- "Parks, Squares & Plazas". Newport News, VA - Official Website. City of Newport News, VA. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- Parks, Squares, and Plazas Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Newport News Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism; accessed April 3, 2008.

- Newport News Park Archived June 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Newport News Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "Hilton Pier Dedicated," Daily Press (Newport News, VA) July 10, 2005, B1-B2

- Parks Division Archived December 5, 2009, at WebCite Newport News Department of Parks, Recreation, and Tourism; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "Newport News TV". YouTube. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- Holmes, Gary. "Nielsen Reports 1.1% increase in U.S. Television Households for the 2006–2007 Season" Archived July 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Nielsen Media Research, September 23, 2006. Retrieved on September 28, 2007.

- "Hampton Roads News Links". abyznewslinks.com. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- "Hampton Roads Magazine". Hampton Roads Magazine. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- "Hampton Roads Radio Links". ontheradio.net. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

- http://geoelections.free.fr/. Retrieved January 13, 2021. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "City Council—City of Newport News". Newport News City Council. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- U.S. Courts – Newport News courthouse. U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia; accessed April 3, 2008.

- Newport News Circuit Court City of Newport News; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "Virginia Accreditation Status" (PDF). Newport News Public Schools. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- "The Apprentice School". Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- About CNU, cnu.edu; accessed April 3, 2008.

- About W&M College of William and Mary; accessed April 3, 2008.

- About ODU Old Dominion University. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- About NSU Archived December 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, nsu.edu; accessed April 3, 2008.

- Hampton Facts, hamptonu.edu; accessed April 3, 2008.

- Why TNCC?, tncc.edu; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport". Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport. Archived from the original on December 4, 2000. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- "Norfolk International Airport Mission and History". Norfolk International Airport. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- "Norfolk International Airport Statistics" (PDF). Norfolk International Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- "Chesapeake Regional Airport". Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- "Passenger Trains for the VA Peninsula 7-17-09". The Hampton Roads Partnership. Archived from the original (PPT) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2009.

- Amtrak Newport News Station, amtrak.com; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "Southeast High Speed Rail". Southeast High Speed Rail. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Greyhound Lines/Carolina Trailways webpage; greyhound.com; accessed July 24, 2015.

- "Routes". Hampton Roads Transit. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- Williamsburg Area Transit Authority webpage; accessed November 13, 2016.

- "Supply System | Newport News, VA - Official Website". www.nnva.gov. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Waterworks City of Newport News website; accessed April 3, 2008.

- "Hampton Roads Sanitation District". Hampton Roads Sanitation District. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- Sister Cities designated by Sister Cities International, Inc. (SCI) Archived May 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on August 18, 2006.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 535.

- Official website