Ultimate tic-tac-toe

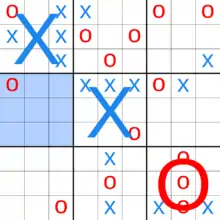

Ultimate tic-tac-toe (also known as super tic-tac-toe, strategic tic-tac-toe, meta tic-tac-toe, tic-tac-tic-tac-toe-toe, or (tic-tac-toe)²[1]) is a board game composed of nine tic-tac-toe boards arranged in a 3 × 3 grid.[2][3] Players take turns playing in the smaller tic-tac-toe boards until one of them wins in the larger tic-tac-toe board. Compared to traditional tic-tac-toe, strategy in this game is conceptually more difficult and has proven more challenging for computers.[4]

Rules

Each small 3 × 3 tic-tac-toe board is referred to as a local board, and the larger 3 × 3 board is referred to as the global board.

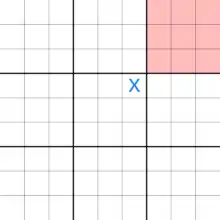

The game starts with X playing wherever they want in any of the 81 empty spots. This move "sends" their opponent to its relative location. For example, if X played in the top right square of their local board, then O needs to play next in the local board at the top right of the global board. O can then play in any one of the nine available spots in that local board, each move sending X to a different local board.

If a move is played so that it is to win a local board by the rules of normal tic-tac-toe, then the entire local board is marked as a victory for the player in the global board.

Once a local board is won by a player or it is filled completely, no more moves may be played in that board. If a player is sent to such a board, then that player may play in any other board.

Another version for the game allows players to continue playing in already won boxes if there are still empty spaces. This allows the game to last longer and involves further strategic moves. This is up to the players on which rule to follow. It was shown in 2020 that this set of rules for the game admits a winning strategy for the first player to move, meaning that the first player to move can always win assuming perfect play.[5]

Game play ends when either a player wins the global board or there are no legal moves remaining, in which case the game is a draw.[3]

Gameplay

Ultimate tic-tac-toe is significantly more complex than most other variations of tic-tac-toe, as there is no clear strategy to playing. This is because of the complicated game branching in this game. Even though every move must be played in a local board, equivalent to a normal tic-tac-toe board, each move must take into account the global board in several ways:

- Anticipating the next move: Each move played in a local board determines where the opponent's next move may be played. This might make moves that may be considered bad in normal tic-tac-toe viable, since the opponent is sent to another local board, and may be unable to immediately respond to them. Therefore, players are forced to consider the larger game board instead of simply focusing on the local board.

- Visualizing the game tree: Visualizing future branches of the game tree is more difficult than single board tic-tac-toe. Each move determines the next move, and therefore reading ahead—predicting future moves—follows a much less linear path. Future board positions are no longer interchangeable, each move leading to starkly different possible future positions. This makes the game tree difficult to visualize, possibly leaving many possible paths overlooked.

- Winning the game: Due to the rules of ultimate tic-tac-toe, the global board is never directly affected. It is only governed by actions that occur in local boards. This means that each local move played is not intended to win the local board, but to win the global board. Local wins are not valuable if they cannot be used to win the global board—in fact, it may be strategic to sacrifice a local board to your opponent in order to win a more important local board yourself. This added layer of complexity makes it harder for humans to analyze the relative importance and significance of moves, and consequently harder to play well.

Computer implementations

While tic-tac-toe is elementary to solve[6] and can be done nearly instantly using depth-first search, ultimate tic-tac-toe cannot be reasonably solved using any brute-force tactics. Therefore, more creative computer implementations are necessary to play this game.

The most common artificial intelligence (AI) tactic, minimax, may be used to play ultimate tic-tac-toe, but has difficulty playing this. This is because, despite having relatively simple rules, ultimate tic-tac-toe lacks any simple heuristic evaluation function. This function is necessary in minimax, for it determines how good a specific position is. Although elementary evaluation functions can be made for ultimate tic-tac-toe by taking into account the number of local victories, these largely overlook positional advantage that is much harder to quantify. Without any efficient evaluation function, most typical computer implementations are weak, and therefore there are few computer opponents that can consistently outplay humans.[4]

However, artificial intelligence algorithms that don't need evaluation functions, like the Monte Carlo tree-search algorithm, have no problem in playing this game. The Monte Carlo tree search relies on random simulations of games to determine how good a position is instead of a positional evaluation and is therefore able to accurately assess how good a current position is. Therefore, computer implementations using these algorithms tend to outperform minimax solutions and can consistently beat human opponents.[2][7]

References

- Epstein, Dave. "NP Completeness in Contemporary Board Games".

- Whitney, George; Janoski, Janine (November 26, 2016). "Group Actions on Winning Games of Super Tic-Tac-Toe". arXiv:1606.04779. Bibcode:2016arXiv160604779G. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Orlin, Ben (June 1, 2013). "Ultimate Tic-Tac-Toe". Math with Bad Drawings. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- Lifshitz, Eytan; Tsurel, David (December 26, 2016). "AI Approaches to Ultimate Tic-Tac-Toe" (PDF). The Rachel and Selim Benin School of Computer Science and Engineering.

- Bertholon, Guillaume; Géraud-Stewart, Rémi; Kugelmann, Axel; Lenoir, Théo; Naccache, David (June 3, 2020). "At Most 43 Moves, At Least 29: Optimal Strategies and Bounds for Ultimate Tic-Tac-Toe". arXiv:2006.02353v2. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Schaefer, Steve (2002). "MathRec Solutions (Tic-Tac-Toe)". Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- Gila, Ofek (June 2, 2016). "What is the Monte Carlo tree search?". We Blog. Retrieved October 18, 2016.