Unionist Party (Canada)

The Unionist Party was a centre-right historical political party in Canada, composed primarily of former members of the Conservative party with some individual Liberal Members of Parliament. It was formed in 1917 by MPs who supported the "Union government" formed by Sir Robert Borden during the First World War, formed the government through the final years of the war, and was a proponent of conscription. It was opposed by the remaining Liberal MPs, who sat as the official opposition.

| Canadian political party | |

| Leader | Robert Borden, Arthur Meighen |

| Founded | October 10, 1917 |

| Dissolved | 1922 |

| Preceded by | Conservative Party Liberal–Unionist |

| Merged into | Conservative Party |

| Headquarters | Ottawa, Ontario |

| Ideology | British imperialism Conservatism Liberalism |

| Political position | Centre to centre-right |

| International affiliation | None |

The Unionist Party continued to exist until 1922, at which time the Conservative elements re-formed the Conservative party.

Formation

In May 1917, Conservative Prime Minister Borden proposed the formation of a national unity government or coalition government to Liberal leader Sir Wilfrid Laurier in order to enact conscription, and to govern for the remainder of the war. Laurier rejected this proposal because of the opposition of his Quebec MPs, and fears that Quebec nationalist leader Henri Bourassa would be able to exploit the situation. Public opinion in Quebec was heavily against conscription, influencing the Liberal opposition to it due to the large number of Liberal MPs from Quebec.[1]

As an alternative to a coalition with Laurier, on October 12, 1917, Borden formed the Union government with a Cabinet of twelve Conservatives, nine Liberals and Independents and one "Labour" member. To represent "labour" and the working class, Borden appointed to the Cabinet Conservative Senator Gideon Decker Robertson who had been appointed to the Senate in January and had links with the conservative wing of the labour movement through his profession as a telegrapher. Robertson, however, was a Tory and not a member of any Labour or socialist party.

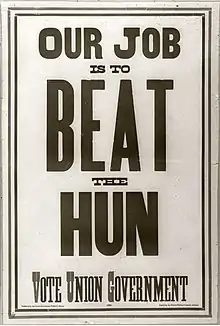

Borden then called an election for December 1917 on the issue of conscription (see also Conscription Crisis of 1917), running as head of the "Unionist Party" composed of Borden's Conservatives, independent MPs, and members of the Liberals who left Laurier's caucus to support conscription.

Supporters of the Borden government ran for parliament as "Unionists", while some of the Liberals running as government supporters preferred to call themselves "Liberal-Unionist". Prime Minister Borden pledged himself during the 1917 campaign to equal suffrage for women. He introduced a bill in 1918 for extending the franchise to women; it passed without division.

This tactic split the Liberal Party: those who did not join the Unionist Party ran as Laurier Liberals. The election resulted in a landslide election victory for Borden.

Borden attempted to continue the Unionist Party after the war and when Arthur Meighen succeeded him in 1920, he renamed it the "National Liberal and Conservative Party" in the hope of making the coalition permanent. The Unionists had never been officially a single party, and therefore lacked the structure of an official party and Meighen hoped to change this.

In the 1921 general election, most of the Liberal-Unionist MPs did not join this party, and ran as Liberals under the leadership of its new leader, William Lyon Mackenzie King. Only a handful ran again as Liberal-Unionists or joined Meighen's renamed party. Prominent Liberal-Unionists who stayed with the Conservatives include Hugh Guthrie and Robert Manion.

Following the defeat of Meighen's government, the "National Liberal and Conservative Party" changed its name to the "Liberal-Conservative Party of Canada", although it was commonly known as the "Conservative Party".

During World War II, the Conservatives attempted to oppose the Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King in the 1940 election by proposing a "national government" along the lines of the previous war's Unionist government. Accordingly, they ran in the election under the name National Government party, but did not repeat the success of the Unionist party and failed to form government.

See also

External links

References

- Armstrong, Elizabeth (Jan 15, 1974). The Crisis of Quebec, 1914-1918. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press.