University of ancient Taxila

The University of ancient Taxila was a renowned ancient institute of higher-learning located in the city of Taxila.

Ruins of Achaemenid city of Taxila, Bhir Mound archaeological site. | |

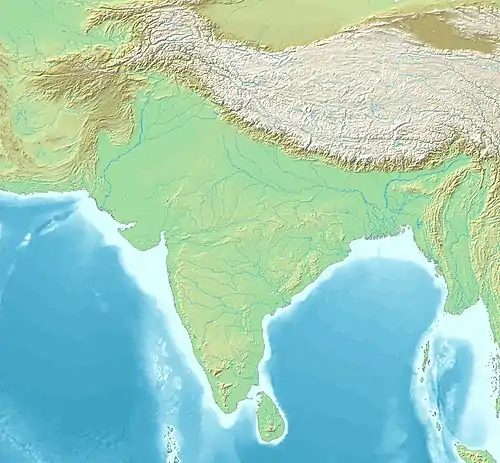

Shown within South Asia | |

| Location | Taxila, modern Pakistan |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33.74°N 72.78°E |

| Type | Centre of learning |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 10th century BCE |

The earliest information about Taxila is from Valmiki Ramayana. In connection with the mention of the victories of King Ramachandra of Ayodhya, we learn that his younger brother Bharata won the country (Gandhara) of Gandharva with the invitation and assistance of his maternal grandfather Kekairaj Ashwapati and appointed his two sons as the rulers there. The Gandharva country was situated on both banks of the Indus River[1]and on its sides, two sons named Taksha and Pushkal of Bharata settled their respective capitals named Taxila and Pushkaravati.[2] Taxila was on the eastern coast of the Indus river. After the Mahabharata war, Parikshit's descendants retained authority there for a few generations and Janamejaya did his Nagayagya there.[3] During the time of Gautama Buddha, King Pukkusati of Gandhara sent his envoy to Magadharaj Bimbisara. capital of the Achaemenid territories in northwestern ancient Indian subcontinent following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley around 515 BCE. Taxila was at the crossroad of the main trade roads of Asia, was probably populated by Persians and many ethnicities coming from the various parts of the Achaemenid Empire.[4][5][6]

The University

The renowned University of Taxila became the greatest learning centre in the region, and allowed for exchanges between people from various cultures. It's widely acknowledged as first example of higher learning in the world history. [7]

The University was particularly renowned for science, especially medicine, and the arts, but both religious and secular subjects were taught, and even subject such as archery or astrology.[8] Students come from distant parts of India.[8] Many Jataka of early Buddhist literature mention students attending the University.[8] It is believed that over 10,000 students from China, Babylon, Syria and Greece in addition to Indian students studied there.[9]

The Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley made Taxila a part of the Achaemenid Empire. The Persian conquest probably made Taxila University a very cosmopolitan environment in which numerous cultures and ethnicities could exchange their knowledge.[8]

The role of Taxila University as a center of knowledge continued under the Maurya Empire and Greek rule (Indo-Greeks) in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE.[8]

The destruction of Toramana in the 5th century CE seem to have put an end to the activities of the University.[10]

Followers of the Buddha

.jpg.webp)

Several contemporaries, and close followers, of the Buddha are said to have studied in Achaemenid Taxila: King Pasenadi of Kosala, a close friend of the Buddha, Bandhula, the commander of Pasedani's army, Aṅgulimāla, a close follower of the Buddha, and Jivaka, court doctor at Rajagriha and personal doctor of the Buddha.[11] According to Stephen Batchelor, the Buddha may have been influenced by the experiences and knowledge acquired by some of his closest followers in the foreign capital of Taxila.[12]

- Story of Angulimala as a student in Taxila

A Buddhist story about Aṅgulimāla (also called Ahiṃsaka, and later a close follower of Buddha), relates how his parents send him to Taxila to study under a well-known teacher. There he excels in his studies and becomes the teacher's favorite student, enjoying special privileges in his teacher's house. However, the other students grow jealous of Ahiṃsaka's speedy progress and seek to turn his master against him.[13] To that end, they make it seem as though Ahiṃsaka has seduced the master's wife.[14]

Other famous students or professors

Charaka

Charaka, the Indian "father of medicine" and one of the leading authorities in Ayurveda, is also said to have studied at Taxila, and practiced there.[15][16]

Pāṇini

The great 5th century BCE Indian grammarian Pāṇini is said to have been born in the northwest, in Shalatula near Attock, not far from Taxila, in what was then a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, but the ethnicity in his name or the way of his life shows that he was of Indian origin.[17][18][19]

Kautilya

Kautilya (also known as Chanakya), the influential Prime Minister to the founder of the Mauryan Empire, Chandragupta Maurya, is also said to have been teaching at Taxila.[20]

Chandragupta Maurya

Buddhist literature states that Chandragupta Maurya, the future founder of the Mauryan Empire, though born near Patna (Bihar) in Magadha, was taken by Chanakya for his training and education to Taxila, and had him educated there in "all the sciences and arts" of the period, including military sciences. There he studied for eight years.[21] The Greek and Hindu texts also state that Kautilya (Chanakya) was a native of the northwest Indian subcontinent, and Chandragupta was his resident student for eight years.[22][23] These accounts match Plutarch's assertion that Alexander the Great met with the young Chandragupta while campaigning in the Punjab.[24][25]

See also

References

- Sindorubhayat: Parshva Desh: Paramshobhan:, Valmiki Ramayana, VII, 100-11

- Raghuvansh fifteenth, 88-9; Valmiki Ramayana, VII, 101.10-11; Vayupurana, 88.190, Mahabharata, First 3.22

- Maha 0, Swargohrana Parva, chapter 5

- Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2016). The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge networks and the early development of universities. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 9781317543268.

- Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 50. ISBN 9780984404308.

- Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 255–256. ISBN 9781588369840.

- Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 125. ISBN 9781588369840.

- Marshall, John (2013). A Guide to Taxila. Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9781107615441.

- https://www.hellotravel.com/stories/top-5-oldest-universities-around-world

- The Pearson CSAT Manual 2011. Pearson Education India. p. 439/ HC.23. ISBN 9788131758304.

- Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 256. ISBN 9781588369840.

- Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 255. ISBN 9781588369840.

- Malalasekera 1960.

- Wilson 2016, p. 286.

- Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2016). The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge networks and the early development of universities. Routledge. p. PT62. ISBN 9781317543268.

- Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009). Ashoka. Penguin UK. p. PT27. ISBN 9788184758078.

- Scharfe, Hartmut (1977). Grammatical Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 89. ISBN 9783447017060.

- Bakshi, S. R. (2005). Early Aryans to Swaraj. Sarup & Sons. p. 47. ISBN 9788176255370.

- Ninan, M. M. (2008). The Development of Hinduism. Madathil Mammen Ninan. p. 97. ISBN 9781438228204.

- Schlichtmann, Klaus (2016). A Peace History of India: From Ashoka Maurya to Mahatma Gandhi. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 29. ISBN 9789385563522.

- Mookerji 1988, pp. 15-18.

- Mookerji 1988, pp. 18-23, 53-54, 140-141.

- Modelski, George (1964). "Kautilya: Foreign Policy and International System in the Ancient Hindu World". American Political Science Review. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 58 (03): 549–560. doi:10.2307/1953131.

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9788120804050.

- "Sandrocottus, when he was a stripling, saw Alexander himself, and we are told that he often said in later times that Alexander narrowly missed making himself master of the country, since its king was hated and despised on account of his baseness and low birth". Plutarch 62-4 "Plutarch, Alexander, chapter 1, section 1".

Sources

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1960), Dictionary of Pāli Proper Names, 1, Delhi: Pali Text Society, OCLC 793535195

- Wilson, Liz (2016), "Murderer, Saint and Midwife", in Holdrege, Barbara A.; Pechilis, Karen (eds.), Refiguring the Body: Embodiment in South Asian Religions, SUNY Press, pp. 285–300, ISBN 978-1-4384-6315-5

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3