Aṅgulimāla

Aṅgulimāla (Pāli language; lit. 'finger necklace')[1][2] is an important figure in Buddhism, particularly within the Theravāda tradition. Depicted as a ruthless brigand who completely transforms after a conversion to Buddhism, he is seen as the example par excellence of the redemptive power of the Buddha's teaching and the Buddha's skill as a teacher. Aṅgulimāla is seen by Buddhists as the "patron saint" of childbirth and is associated with fertility in South and Southeast Asia.

Aṅgulimāla | |

|---|---|

Angulimala chases Gautama Buddha | |

| Other names | Ahiṃsaka, Gagga Mantānīputta |

| Personal | |

| Born | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Education | Taxila |

| Other names | Ahiṃsaka, Gagga Mantānīputta |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Buddha |

| Translations of Aṅgulimāla | |

|---|---|

| English | lit. 'finger necklace' ('he who wears fingers as a necklace') |

| Sanskrit | Aṅgulimāliya, Aṅgulimālya[1] |

| Pali | Aṅgulimāla |

| Burmese | အင်္ဂုလိမာလ (IPA: [ʔɪ̀ɰ̃ɡṵlḭmàla̰]) |

| Chinese | 央掘魔羅 (Pinyin: Yāngjuémóluó) |

| Khmer | អង្គុលីមាល៍ (Ankulimea) |

| Sinhala | අංගුලිමාල |

| Thai | องคุลิมาล, องคุลีมาล (RTGS: Ongkhuliman) |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

Aṅgulimāla's story can be found in numerous sources in Pāli, Sanskrit, Tibetan and Chinese. Aṅgulimāla is born Ahiṃsaka. He grows up as an intelligent young man in Sāvatthī, and during his studies becomes the favorite student of his teacher. However, out of jealousy, fellow students set him up against his teacher. In an attempt to get rid of Aṅgūlimāla, the teacher sends him on a deadly mission to find a thousand human fingers to complete his studies. Trying to accomplish this mission, Aṅgulimāla becomes a cruel brigand, killing many and causing entire villages to emigrate. Eventually, this causes the king to send an army to catch the killer. Meanwhile, Aṅgulimāla's mother attempts to interfere, almost causing her to be killed by her son as well. The Buddha manages to prevent this, however, and uses his power and teachings to bring Aṅgulimāla to the right path. Aṅgulimāla becomes a follower of the Buddha, and to the surprise of the king and others, becomes a monk under his guidance. Villagers are still angry with Aṅgulimāla, but this is improved somewhat when Aṅgulimāla helps a mother with childbirth through an act of truth.

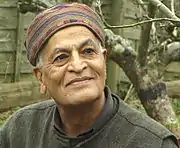

Scholars have theorized that Aṅgulimāla may have been part of a violent cult before his conversion. Indologist Richard Gombrich has suggested that he was a follower of an early form of Tantra, but this claim has been debunked.[3][4] Buddhists consider Aṅgulimāla a symbol of spiritual transformation, and his story a lesson that everyone can change their life for the better, even the least likely people. This inspired the official Buddhist prison chaplaincy in the UK to name their organization after him. Moreover, Aṅgulimāla's story is referred to in scholarly discussions of justice and rehabilitation, and is seen by theologian John Thompson as a good example of coping with moral injury and an ethics of care. Aṅgulimāla has been the subject of movies and literature, with a Thai movie of the same name choosing to depict him following the earliest sources, and the book The Buddha and the Terrorist by Satish Kumar adapting the story as a non-violent response to the Global War on Terror.

Textual sources and epigraphical findings

The story of Aṅgulimāla is most well-known in the Theravāda tradition.[5] Two texts in the early discourses in the Pāli language are concerned with Aṅgulimāla's initial encounter with the Buddha and his conversion, and are believed to present the oldest version of the story.[6][7][note 1] The first is the Theragāthā, probably the oldest of the two,[5] and the second is the Aṅgulimāla Sutta in the Majjhima Nikāya.[9] Both offer a short description of Aṅgulimāla's encounter with the Buddha, and do not mention much of the background information later incorporated into the story (such as Aṅgulimāla being placed under oath by a teacher).[10][5] Apart from the Pāli texts, the life of Aṅgulimāla is also described in Tibetan and Chinese texts which originate from Sanskrit.[10][7] The Sanskrit collection called Saṃyuktāgama from the early Mūlasārvastivāda school, has been translated in two Chinese texts (in the 4th–5th century CE) by the early Sarvāstivāda and Kāśyapīya schools and also contains versions of the story.[11][7][12] A text translated in Chinese from the Sanskrit Ekottara Agāma by the Mahāsaṃghika school is also known. Furthermore, three other Chinese texts dealing with Aṅgulimāla have also been found, of unknown origin but different from the first three Chinese texts.[13]

Apart from these early texts, there are also later renderings, which appear in the commentary to the Majjhima Nikāya attributed to Buddhaghosa (5th century CE) and the Theragāthā commentary attributed to Dhammapāla (6th century CE).[10] The two commentaries do not appear to be independent of one another: it appears that Dhammapāla has copied or closely paraphrased Buddhaghosa, although adding explanation of some inconsistencies.[6][7] The earliest accounts of Aṅgulimāla's life emphasize the fearless violence of Aṅgulimāla and, by contrast, the peacefulness of the Buddha. Later accounts attempt to include more detail and clarify anything that might not conform with Buddhist doctrine.[14] For example, one problem that is likely to have raised questions is the sudden transformation from a killer to an enlightened disciple—later accounts try to explain this.[15] Later accounts also include more miracles, however, and together with the many narrative details this tends to overshadow the main points of the story.[16] The early Pāli discourses (Pali: sutta) do not provide for any motive for Aṅgulimāla's actions, other than sheer cruelty.[17] Later texts may represent attempts by later commentators to "rehabilitate" the character of Aṅgulimāla, making him appear as a fundamentally good human being entrapped by circumstance, rather than as a vicious killer.[18][19] In addition to the discourses and verses, there are also Jātaka tales, the Milindapañhā, and parts of the monastic discipline that deal with Aṅgulimāla, as well as the later Mahāvaṃsa chronicle.[20]

Later texts from other languages that relate Aṅgulimāla's life include the Avadāna text called Sataka,[21] as well as a later collection of tales called Discourse on the Wise and the Fool, which exists in Tibetan and Chinese.[22] There are also travel accounts of Chinese pilgrims that mention Aṅgulimāla briefly.[23] In addition to descriptions of the life of Aṅgulimāla, there is a Mahāyāna discourse called the Aṅgulimālīya Sūtra, which Gautama Buddha addresses to Aṅgulimāla. This is one of the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtras, a group of discourses that deal with the Buddha Nature.[1][24] There is another sūtra with the same name, referred to in Chinese texts, which was used to defend the Buddhist stance against alcoholic beverages. This text has not been found, however.[25] Apart from textual evidence, early epigraphic evidence has also been found. One of the earliest reliefs that depicts Aṅgulimāla dates from approximately 3rd century BCE.[26]

Story

Previous incarnations

The texts describe a previous incarnation before Aṅgulimāla met the Buddha Gautama. In this life, he was born as a man-eating king turned yaksha (Pali: yakkha, a sort of demon; Sanskrit: yakṣa),[27][28] in some texts called Saudāsa.[29] Saudāsa develops an interest in consuming human flesh when he is served the flesh of a dead baby. When he asks for more, his subjects start to fear for their children's safety and he is driven from his own kingdom.[30][note 2] Growing into a monster, Saudāsa meets a deity that promises Saudāsa can retrieve his status as king if he sacrifices one hundred other kings.[28] Having killed 99 kings, a king called Sutasoma changes Saudāsa's mind and makes him a religious man, and he gives up all violence. The texts identify Sutasoma with a previous incarnation of the Buddha,[28][29] and Saudāsa with a previous incarnation of Aṅgulimāla.[31]

According to the Ekottara Agāma, however, in a previous incarnation Aṅgulimāla is a crown prince, whose goodness and virtue irritate his enemies. When his enemies kill him, he takes a vow just before his death that he may avenge his death, and attain Nirvana in a future life under the guidance of a master. In this version, the killings by Aṅgulimāla's are therefore justified as a response to the evil done to him in a past life, and his victims receive the same treatment they once subjected Aṅgulimāla with.[32]

Youth

In most texts, Aṅgulimāla is born in Sāvatthī,[29][note 3] in the brahman (priest) caste of the Gagga clan, his father Bhaggava being the chaplain of the king of Kosala, and his mother called Mantānī.[21] According to commentarial texts, omens seen at the time of the child's birth (the flashing of weapons and the appearance of the "constellation of thieves" in the sky)[21] indicate that the child is destined to become a brigand.[27][33] As the father is interpreting the omens for the king, the king asks whether the child will be a lone brigand or a band leader. When Bhaggava replies that he will be a lone brigand, the king decides to let it live.[33]

Buddhaghosa relates that the father names the child Ahiṃsaka, meaning 'the harmless one'.[21] This is derived from the word ahiṃsa (non-violence), because no-one is hurt at his birth, despite the bad omens.[1] The commentary by Dhammapāla states that he is initially named Hiṃsaka ('the harmful one') by the worried king, but that the name is later changed.[21]

Having grown up, Ahiṃsaka is handsome, intelligent and well-behaved.[27][11] His parents send him to Taxila to study under a well-known teacher. There he excels in his studies and becomes the teacher's favorite student, enjoying special privileges in his teacher's house. However, the other students grow jealous of Ahiṃsaka's speedy progress and seek to turn his master against him.[21] To that end, they make it seem as though Ahiṃsaka has seduced the master's wife.[27] Unwilling or unable to attack Ahiṃsaka directly,[note 4] the teacher says that Ahiṃsaka's training as a true brahman is almost complete, but that he must provide the traditional final gift offered to a teacher and then he will grant his approval. As his payment, the teacher demands a thousand fingers, each taken from a different human being, thinking that Aṅgulimāla will be killed in the course of seeking this grisly prize.[21][11][note 5] According to Buddhaghosa, Ahiṃsaka objects to this, saying he comes from a peaceful family, but eventually the teacher persuades him.[37] But according to other versions, Ahiṃsaka does not protest against the teacher's command.[27]

In another version of the story, the teacher's wife tries to seduce Ahiṃsaka. When the latter refuses her advances, she is spiteful and tells the teacher Ahiṃsaka has tried to seduce her. The story continues in the same way.[1][11]

Life as a brigand

Following his teacher's bidding, Aṅgulimāla becomes a highwayman, living on a cliff in a forest called Jālinī where he can see people passing through, and kills or hurts those travelers.[39][21][27] He becomes infamous for his skill in seizing his victims.[40] When the people start to avoid roads, he enters villages and drags people from their homes to kill them. Entire villages become abandoned.[21][37] He never takes clothes or jewels from his victims, only fingers.[37] To keep count of the number of victims that he has taken, he strings them on a thread and hangs them on a tree. However, because birds begin to eat the flesh from the fingers, he starts to wear them as a sacrificial thread. Thus he comes to be known as Aṅgulimāla, meaning 'necklace of fingers'.[1][37] In some reliefs, he is depicted as wearing a headdress of fingers rather than a necklace.[41]

Meeting the Buddha

.jpg.webp)

Surviving villagers migrate from the area and complain to Pasenadi, the king of Kosala.[42][43] Pasenadi responds by sending an army of 500 soldiers to hunt down Aṅgulimāla.[44] Meanwhile, Aṅgulimāla's parents hear about the news that Pasenadi is hunting an outlaw. Since Aṅgulimāla was born with bad omens, they conclude it must be him. Although the father prefers not to interfere,[note 6] the mother disagrees.[42][43][note 7] Fearing for her son's life, she sets out to find her son, warn him of the king's intent and take care of him.[45][27] The Buddha perceives through meditative vision (Pali: abhiññā) that Aṅgulimāla has slain 999 victims, and is desperately seeking a thousandth.[46][note 8] If the Buddha is to encounter Aṅgulimāla that day, the latter will become a monk and subsequently attain abhiññā.[46] However, if Aṅgulimāla is to kill his mother instead, she will be his thousandth victim and he will be unsavable,[1][43] since matricide in Buddhism is considered one of the five worst actions a person can commit.[48][49]

The Buddha sets off to intercept Aṅgulimāla,[21] despite being warned by local villagers not to go.[17][50] On the road through the forest of Kosala, Aṅgulimāla first sees his mother.[1] According to some versions of the story, he then has a moment of reconciliation with her, she providing food for him.[51] After some deliberation, however, he decides to make her his thousandth victim. But then when the Buddha also arrives, he chooses to kill him instead. He draws his sword, and starts running towards the Buddha. But although Aṅgulimāla is running as fast as he can, he cannot catch up with the Buddha who is walking calmly.[1] The Buddha is using some supernatural accomplishment (Pali: iddhi; Sanskrit: ṛddhi) that affects Aṅgulimāla:[40][7] one text states the Buddha through these powers contracts and expands the earth on which they stand, thus keeping a distance of Aṅgulimāla.[52] This bewilders Aṅgulimāla so much that he calls to the Buddha to stop. The Buddha then says that he himself has already stopped, and that it is Aṅgulimāla who should stop:[1][53]

I, Angulimala, am standing still (Pali: ṭhita), having for all beings laid aside the rod (Pali: daṇḍa); but you are unrestrained (Pali: asaññato) regarding creatures; therefore, I am standing still, you are not standing still.[40]

Aṅgulimāla asks for further explanation, after which the Buddha says that a good monk should control his desires.[54] Aṅgulimāla is impressed by the Buddha's courage,[55] and struck with guilt about what he has done.[56] After listening to the Buddha, Aṅgulimāla reverently declares himself converted, vows to cease his life as a brigand and joins the Buddhist monastic order.[57][58][59] He is admitted in the Jetavana monastery.[45]

Life as a monk and death

.jpg.webp)

Meanwhile, King Pasenadi sets out to kill Aṅgulimāla. He stops first to pay a visit to the Buddha and his followers at the Jetavana monastery.[13] He explains to the Buddha his purpose, and the Buddha asks how the king will respond if he were to discover that Aṅgulimāla had given up the life of a highwayman and become a monk. The king says that he would salute him and offer to provide for him in his monastic vocation. The Buddha then reveals that Aṅgulimāla is sitting only a few feet away, his hair and beard shaven off, a member of the Buddhist order. The king, astounded but also delighted, addresses Aṅgulimāla by his clan and mother's name (Pali: Gagga Mantānīputta) and offers to donate robe materials to Aṅgulimāla. Aṅgulimāla, however, does not accept the gift, because of an ascetic training he observes.[21][11]

In the end, the king chooses not to persecute Aṅgulimāla. This passage would agree with Buddhologist André Bareau's observation that there was an unwritten agreement of mutual non-interference between the Buddha and kings and rulers of the time.[60]

Later, Aṅgulimāla comes across a young woman undergoing difficult labor during a childbirth.[note 9] Aṇgulimāla is profoundly moved by this, and understands pain and feels compassion to an extent he did not know when he was still a brigand.[61][59][47] He goes to the Buddha and asks him what he can do to ease her pain. The Buddha tells Aṅgulimāla to go to the woman and say:

Sister, since I was born, I do not recall that I have ever intentionally deprived a living being of life. By this truth, may you be well and may your infant be well.

Aṅgulimāla points out that it would be untrue for him to say this, to which the Buddha responds with this revised stanza:

Sister, since I was born with noble birth, I do not recall that I have ever intentionally deprived a living being of life. By this truth, may you be well and may your infant be well.[1] [emphasis added]

The Buddha is here drawing Angulimala's attention to his choice of having become a monk,[1] describing this as a second birth that contrasts with his previous life as a brigand.[62][17] Jāti means birth, but the word is also glossed in the Pāli commentaries as clan or lineage (Pali: gotta). Thus, the word jāti here also refers to the lineage of the Buddhas, i.e. the monastic community.[63]

After Aṅgulimāla makes this "act of truth", the woman safely gives birth to her child. This verse later became one of the protective verses, commonly called the Aṅgulimāla paritta.[64][65] Monastics continue to recite the text during blessings for pregnant women in Theravāda countries,[66][67] and often memorize it as part of monastic training.[51] Thus, Aṅgulimāla is widely seen by devotees as the "patron saint" of childbirth. Changing from a murderer to a person seen to ensure safe childbirth has been a huge transformation.[9]

This event helps Aṅgulimāla to find peace.[61] After performing the act of truth, he is seen to "bring life rather than death to the townspeople"[61] and people start to approach him and provide him with almsfood.[68]

However, a resentful few cannot forget that he was responsible for the deaths of their loved ones. With sticks and stones they attack him as he walks for alms. With a bleeding head, torn outer robe and a broken alms bowl, Aṅgulimāla manages to return to the monastery. The Buddha encourages Aṅgulimāla to bear his torment with equanimity; he indicates that Aṅgulimāla is experiencing the fruits of the karma that would otherwise have condemned him to hell.[21][1][69] Having become an enlightened disciple, Aṅgulimāla remains firm and invulnerable in mind.[1] According to Buddhist teachings, enlightened disciples cannot create any new karma, but they may still be subject to the effects of old karma that they once did.[70][59] The effects of his karma are inevitable, and even the Buddha cannot stop them from occurring.[71]

After having admitted Aṅgulimāla in the monastic order, the Buddha issues a rule that from now on, no criminals should be accepted as monks in the order.[21][72] Buddhaghosa states that Aṅgulimāla dies shortly after becoming a monk.[21][72] After his death, a discussion arises among the monks as to what Aṅgulimāla's afterlife destination is. When the Buddha states that Aṅgulimāla has attained Nirvana, this surprises some monks. They wonder how it is possible for someone who killed so many people to still attain enlightenment. The Buddha responds that even after having done much evil, a person still has a possibility to change for the better and attain enlightenment.[73]

Analysis

.jpg.webp)

Historical

The giving of goodbye gifts to one's teacher was customary in ancient India. There is an example in the "Book of Pauṣya"[note 10] of the Vedic epic Mahābharatha. Here the teacher sends his disciple Uttanka away after Uttanka has proven himself worthy of being trustworthy and in the possession of all the Vedic and Dharmashastric teachings. Uttanka says to his teacher:

"What can I do for you that pleases you (Sanskrit: kiṃ te priyaṃ karavāni), because thus it is said: Whoever answers without [being in agreement with] the Dharma, and whoever asks without [being in agreement with] the Dharma, either occurs: one dies or one attracts animosity."

Indologist Friedrich Wilhelm maintains that similar phrases already occur in the Book of Manu (II,111) and in the Institutes of Vishnu. By taking leave of their teacher and promising to do whatever their teacher asks of them, brings, according to the Vedic teachings, enlightenment or a similar attainment. It is therefore not unusual that Aṅgulimāla is described to do his teacher's horrible bidding—although being a good and kind person at heart—in the knowledge that in the end he will reap the highest attainment.[74]

Indologist Richard Gombrich has postulated that the story of Aṅgulimāla may be a historical encounter between the Buddha and a follower of an early Saivite or Shakti form of tantra.[75] Gombrich reaches this conclusion on the basis of a number of inconsistencies in the texts that indicate possible corruption,[76] and the fairly weak explanations for Aṅgulimāla's behavior provided by the commentators.[77][78] He notes that there are several other references in the early Pāli canon that seem to indicate the presence of devotees of Śaiva, Kāli, and other divinities associated with sanguinary (violent) tantric practices.[79] The textual inconsistencies discovered could be explained through this theory.[80]

The idea that Aṅgulimāla was part of a violent cult was already suggested by the Chinese pilgrim Xuan Zang (602–64 CE). In his travel accounts, Xuan Zang states that Aṅgulimāla's was taught by his teacher that he would be born in the Brahma heaven if he killed a Buddha. A Chinese early text gives a similar description, stating that Aṅgulimāla's teacher followed the gruesome instructions of his guru, to attain immortality.[81] Xuan Zang's suggestion was further developed by European translators of Xuan Zang's travel accounts in the early twentieth century, but partly based on translation errors.[82][83] Regardless, Gombrich is the first recent scholar to postulate this idea. However, Gombrich's claim that tantric practices existed before the finalization of the canon of Buddhist discourses (two to three centuries BCE) goes against mainstream scholarship. Scholarly consensus places the arising of the first tantric cults about a thousand years later, and no corroborating evidence has been found, whether textual or otherwise, of earlier sanguinary tantric practices.[78][84] Though Gombrich argues that there other, similar antinomian practices (going against moral norms) which are only mentioned once in Buddhist scriptures and for which no evidence can be found outside of the scriptures,[85] Buddhist Studies scholars Mudagamuwa and Von Rospatt dismiss these as incorrect examples. They also take issue with Gombrich's metrical arguments, thus disagreeing with Gombrich's hypotheses with regard to Aṅgulimāla. They do consider it possible, however, that Angulimāla's violent practices were part of some kind of historical cult.[86] Buddhist Studies scholar L. S. Cousins has also expressed doubts about Gombrich's theory.[4]

In the Chinese translation of the Damamūkhāvadāna by Hui-chiao,[87] as well as in archaeological findings,[29] Aṅgulimāla is identified with the mythological Hindu king Kalmashapada or Saudāsa, known since Vedic times. Ancient texts often describe Saudāsa's life as Aṅgulimāla's previous life, and both characters deal with the problem of being a good brahman.[29]

Studying art depictions in the Gandhāra region, Archeologist Maurizio Taddei theorizes that the story of Aṅgulimāla may point at an Indian mythology with regard to a yakṣa living in the wild. In many depictions Aṅgulimāla is wearing a headdress, which Taddei describes as an example of dionysian-like iconography. Art historian Pia Brancaccio argues, however, that the headdress is an Indian symbol used for figures associated with the wild or hunting.[41] She concurs with Taddei that depictions of Aṅgulimāla, especially in Gandhāra, are in many ways reminiscent of dionysian themes in Greek art and mythology, and influence is highly likely.[88] However, Brancaccio argues that the headdress was essentially an Indian symbol, used by artists to indicate Aṅgulimāla belonged to a forest tribe, feared by the early Buddhists who were mostly urban.[89]

Doctrinal

A bandit I used to be,

renowned as Aṅgulimāla.

Swept along by a great flood,

I went to the Buddha as refuge...

This has come well & not gone away,

it was not badly thought through for me.

The three knowledges

have been attained;

the Buddha’s bidding,

done.

transl. Thanissaro Bhikkhu, quoted in Thompson[45]

Among Buddhists, Aṅgulimāla is one of the most well-known stories.[57] Not only in modern times: in ancient times, two important Chinese pilgrims travelling to India reported about the story, and reported about the places they visited that were associated with Aṅgulimāla's life.[45] From a Buddhist perspective, Aṅgulimāla's story serves as an example that even the worst of people can overcome their faults and return to the right path.[90] The commentaries uphold the story as an example of good karma destroying evil karma.[21] Buddhists widely regard Aṅgulimāla as a symbol of complete transformation[27] and as a showcase that the Buddhist path can transform even the least likely initiates.[91] Buddhists have raised Aṅgulimāla's story as an example of the compassion (Pali: karuṇa) and supernatural accomplishment (Pali: iddhi) of the Buddha.[21] Aṅgulimāla's conversion is cited as a testimony to the Buddha's capabilities as a teacher,[12] and as an example of the healing qualities of the teaching of the Buddha (Dharma).[92]

Through his reply, the Buddha connects the notion of 'refraining from harming' (Pali: avihiṃsa) with stillness, which is the cause and effect of not harming. Furthermore, the story illustrates that there is spiritual power in such stillness, as the Buddha is depicted as outrunning the violent Aṅgulimāla. Though this is explained as being the result of the Buddha's supernatural accomplishment, the deeper meaning is that "... 'the spiritually still person' can move faster than the 'conventionally active' person". In other words, spiritual achievement is only possible through non-violence.[40] Furthermore, this stillness refers to the Buddhist notion of liberation from karma: as long as one cannot escape from the endless law of karmic retribution, one can at least lessen one's karma by practicing non-violence. The texts describe this as form of stillness, as opposed to the continuous movement of karmic retribution.[93]

Other

.jpg.webp)

The story of Aṅgulimāla illustrates how criminals are affected by their psycho-social and physical environment.[94] Jungian analyst Dale Mathers theorizes that Ahiṃsaka started to kill because his meaning system had broken down. He was no longer appreciated as an academic talent. His attitude could be summarized as "I have no value: therefore I can kill. If I kill, then that proves I have no value".[53] Summarizing the life of Aṅgulimāla, Mathers writes, "[h]e is ... a figure who bridges giving and taking life."[95] Similarly, referring to the psychological concept of moral injury, theologian John Thompson describes Aṅgulimāla as someone who is betrayed by an authority figure but manages to recover his eroded moral code and repair the community he has affected.[96] Survivors of moral injury need a clinician and a community of people that face struggles together but deal with those in a safe way; similarly, Aṅgulimāla is able to recover from his moral injury due to the Buddha as his spiritual guide, and a monastic community that leads a disciplined life, tolerating hardship.[97] Thompson has further suggested Aṅgulimāla's story might be used as a sort of narrative therapy[96] and describes the ethics presented in the narrative as inspiring responsibility. The story is not about being saved, but rather saving oneself with help from others. [98]

Ethics scholar David Loy has written extensively about Aṅgulimāla's story and the implications it has for the justice system. He believes that in Buddhist ethics, the only reason offenders should be punished is to reform their character. If an offender, like Aṅgulimāla, has already reformed himself, there is no reason to punish him, even as a deterrent. Furthermore, Loy argues that the story of Aṅgulimāla does not include any form of restorative or transformative justice, and therefore considers the story "flawed" as an example of justice.[99] Former politician and community health scholar Mathura Shrestha, on the other hand, describes Aṅgulimāla's story as "[p]robably the first concept of transformative justice", citing Aṅgulimāla's repentance and renunciation of his former life as a brigand, and the pardon he eventually receives from relatives of victims.[100] Writing about capital punishment, scholar Damien Horigan notes that rehabilitation is the main theme of Aṅgulimāla's story, and that witnessing such rehabilitation is the reason why King Pasenadi does not persecute Aṅgulimāla.[101]

In Sri Lankan pre-birth rituals, when the Aṅgulimāla Sutta is chanted for a pregnant woman, it is custom to surround her with objects symbolizing fertility and reproduction, such as parts of the coconut tree and earthen pots.[102] Scholars have pointed out that in Southeast Asian mythology, there are links between bloodthirsty figures and fertility motifs.[61][103] The shedding of blood can be found in both violence and childbirth, which explains why Aṅgulimāla is both depicted as a killer and a healer with regard to childbirth.[103]

With regard to the passage when the Buddha meets Aṅgulimāla, feminist scholar Liz Wilson concludes that the story is an example of cooperation and interdependence between the sexes: both the Buddha and Aṅgulimāla's mother help to stop him.[104] Similarly, Thompson argues that mothers play an important role in the story, also citing the passage of the mother trying to stop Aṅgulimāla, as well as Aṅgulimāla healing a mother giving childbirth. Furthermore, both the Buddha and Aṅgulimāla take on motherly roles in the story.[105] Although many ancient Indian stories associate women with qualities like foolishness and powerlessness, Aṅgulimāla's story accepts feminine qualities, and the Buddha acts as a wise adviser to use those qualities in a constructive way.[106] Nevertheless, Thompson does not consider the story feminist in any way, but does argue it contains a feminine kind of ethics of care, rooted in Buddhism.[92]

In modern culture

Throughout Buddhist history, Aṅgulimāla's story has been depicted in many art forms,[12] some of which can be found in museums and Buddhist heritage sites. In modern culture, Aṅgulimāla still plays an important role.[24] In 1985, the British-born Theravāda monk Ajahn Khemadhammo founded Angulimala, a Buddhist Prison Chaplaincy organization in the UK.[107][108] It has been recognized by the British government as the official representative of the Buddhist religion in all matters concerning the British prison system, and provides chaplains, counselling services, and instruction in Buddhism and meditation to prisoners throughout England, Wales, and Scotland.[107] The name of the organization refers to the power of transformation illustrated by Aṅgulimāla's story.[27][24] According to the website of the organization, "The story of Angulimala teaches us that the possibility of Enlightenment may be awakened in the most extreme of circumstances, that people can and do change and that people are best influenced by persuasion and above all, example."[109]

In popular culture, Aṅgulimāla's legend has received considerable attention. The story has been the main subject of at least three movies.[24] In 2003, Thai director Suthep Tannirat attempted to release a film named Angulimala. Over 20 conservative Buddhist organizations in Thailand launched a protest, however, complaining that the movie distorted Buddhist teachings and history, and introduced Hindu and theistic influences not found in the Buddhist scriptures.[110][111][112] The Thai film censorship board rejected appeals to ban the film, stating it did not distort Buddhist teachings. They did insist that the director cut two scenes of violent material.[113][114] The conservative groups were offended by the depiction of Aṅgulimāla as a brutal murderer, without including the history which led him to become such a violent brigand. Tannirat defended himself, however, arguing that although he had omitted interpretations from the commentaries, he had followed the early Buddhist discourses precisely.[112] Tannirat's choice to only use the early accounts, rather than the popular tales from the commentaries, was precisely what led to the protests.[24][115]

Satish Kumar, The Buddha and the Terrorist, quoted in Thompson[116]

Aṅgulimāla has also been the subject of literary works.[116] In 2006, peace activist Satish Kumar retold the story of Aṅgulimāla in his short book The Buddha and the Terrorist. The books deals with the Global War on Terror, reshaping and combining various accounts of Aṅgulimāla, who is described as a terrorist.[116] The book emphasizes the passage when the Buddha accepts Aṅgulimāla in the monastic order, effectively preventing King Pasenadi from punishing him. In Kumar's book, this action leads to backlash from an enraged public, who demand to imprison both Aṅgulimāla and the Buddha. Pasenadi organizes a public trial in the presence of villagers and the royal court, in which the assembly can decide what to do with the two accused. In the end, however, the assembly decides to release the two, when Aṅgulimāla admits to his crimes and Pasenadi gives a speech emphasizing forgiveness rather than punishment.[116] This twist in the story sheds a different light on Aṅgulimāla, whose violent actions ultimately lead to the trial and a more non-violent and just society.[117] Writing about Buddhist texts and Kumar's book, Thompson reflects that ahiṃsa in Buddhism may have different shades of meaning in different contexts, and often does not mean passively standing by, or non-violence as usually understood.[118][92]

Finally, Angulimala is one of the protagonists in Karl Gjellerup’s novel Der Pilger Kamanita (The Pilgrim Kamanita, 1906) where he recounts the story of his conversion to Vasitthi who joins the Buddhist order the following day after a profuse alms-giving and after attending the exposition of the Buddhist teaching in the Siṃsapa Grove in the city of Kosambī.[119]

See also

- Conversion of Paul the Apostle - a similar story from the Christian Bible

Notes

- In comparison, in 1994 scholars dated the life of the Buddha between the 5th and 4th century BCE.[8]

- The passage on eating dead babies can only be found in one Chinese version of the story, and may have been added in to criticize such practices in 5th-century China.[30]

- In two of the early Chinese texts, Aṅgulimāla is born in Magadha or Aṅga, and King Pasenadi does not make any appearance.[11][13]

- Dhammapāla states that Ahiṃsaka is as "strong as seven elephants", while another text states that the teacher worries his reputation will suffer if he is found to have murdered a student.[34][35]

- Some versions of the story mention hundred fingers, while others mention thousand.[34][36] Dhammapāla states that Aṅgulimāla is required to fetch a thousand fingers from right hands,[37] seemingly unaware that this could be achieved by killing 200 people,[37] or by taking the fingers from people who were already dead.[14] Buddhaghosa states, on the other hand, that Angulimāla is told to "kill a thousand legs", and gathers fingers only as an aid to keep an accurate count.[38]

- Buddhaghosa says he does not dare to, whereas Dhammapāla says he believes he has "no use for such a son".[43]

- Buddhologist André Bareau and theologian John Thompson have argued that the passage of the mother trying to interfere has been added to the original story later, but Asian Studies scholar Monika Zin notes that the mother already appears in early Buddhist art.[34][45]

- According to some versions, however, the Buddha hears about Aṅgulimāla from monks, who have gone for alms round and have seen the complaining villagers at Pasenadi's palace.[47]

- This passage does not appear in all versions of the Tripiṭaka.[11]

- In Pausyaparvan, Mahābharatha 1,3.

References

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013). "Aṅgulimāla" (PDF). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 135 n.1.

- Mudagamuwa & Von Rospatt 1998, pp. 170–3.

- Cousins, L. S. (24 December 2009). "Review of Richard F. Gombrich: How Buddhism began: the conditioned genesis of the early teachings, 1996". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 62 (2): 373. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00017109.

- Thompson 2015, p. 161.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 137.

- Thompson 2015, p. 162.

- Norman, K.R. (1994). A Philological Approach to Buddhism: The Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai Lectures (PDF). School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. p. 39.

- Wilson 2016, p. 285.

- Wilson 2016, p. 288.

- Zin 2005, p. 707.

- Analayo 2008, p. 135.

- Bareau 1986, p. 655.

- Thompson 2017, p. 176.

- Bareau 1986, p. 654.

- Analayo 2008, p. 147.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 136.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 141.

- Kosuta 2017, p. 36.

- Thompson 2015, pp. 161–2.

- Malalasekera 1960.

- Analayo 2008, p. 140.

- Brancaccio 1999, p. 105.

- Thompson 2015, p. 164.

- Wang-Toutain, Françoise (1999). "Pas de boissons alcoolisées, pas de viande : une particularité du bouddhisme chinois vue à travers les manuscrits de Dunhuang" [No alcoholic beverages, no meat: one particular characteristic of Chinese Buddhism, seen through the manuscripts of Dunhuang]. Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie (in French). 11 (1): 101–2, 105, 112–5. doi:10.3406/asie.1999.1151.

- Zin 2005, p. 709.

- Wilson 2016, p. 286.

- Barrett 2004, p. 180.

- Zin 2005, p. 706.

- Barrett 2004, p. 181.

- Wilkens, Jens (2004). "Studien Zur Alttürkischen Daśakarmapathāvadānamālā (2): Die Legende Vom Menschenfresser Kalmāṣapāda" [Studies of the Old Turkish Daśakarmapathāvadānamālā (2): The Legend of the Man-eater Kalmāṣapāda]. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (in German). 57 (2): 169. JSTOR 23658630.

- Bareau 1986, pp. 656–7.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 138.

- Zin 2005, p. 708.

- Gombrich 2006, pp. 138–9.

- Analayo 2008, p. 141.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 139.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 142.

- Lamotte, Etienne (1988). History of Indian Buddhism: From the Origins to the Saka Era. Université catholique de Louvain, Institut orientaliste. p. 22. ISBN 906831100X.

- Wiltshire 1984, p. 91.

- Brancaccio 1999, pp. 108–12.

- Wilson 2016, pp. 293–4.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 140.

- Loy 2009, p. 1246.

- Thompson 2015, p. 163.

- Wilson 2016, p. 298 n.30.

- Bareau 1986, p. 656.

- Kosuta 2017, pp. 40–1.

- Analayo 2008, p. 146.

- van Oosten 2008, p. 251.

- Thompson 2017, p. 183.

- Analayo 2008, p. 142.

- Mathers 2013, p. 127.

- Thompson 2015, pp. 162–3.

- Analayo 2008, p. 145.

- Thompson 2017, p. 177.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 135.

- Analayo 2008, pp. 142–3.

- van Oosten 2008, p. 252.

- Thompson 2015, pp. 166–7.

- Langenberg, Amy Paris (2013). "Pregnant Words: South Asian Buddhist Tales of Fertility and Child Protection". History of Religions. 52 (4): 351. doi:10.1086/669645. JSTOR 10.1086/669645.

- Wilson 2016, p. 293.

- Wilson 2016, pp. 297–8 n.24.

- Swearer, D.K. (2010). The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia (PDF). SUNY Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-4384-3251-9.

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013). "Aṅgulimāla, Paritta, Satyāvacana" (PDF). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- Appleton, Naomi (2013). Jataka Stories in Theravada Buddhism: Narrating the Bodhisatta Path. Ashgate Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4094-8131-7.

- Eckel, Malcolm David (2001). "Epistemological Truth". In Neville, Robert Cummings (ed.). Religious Truth: A Volume in the Comparative Religious Ideas. Albany: SUNY Press. pp. 67–8. ISBN 0-7914-4777-4.

- Parkum, Virginia Cohn; Stultz, J. Anthony (2012). "The Aṅgulimāla Lineage: Buddhist Prison Ministries". In Queen, Christopher S. (ed.). Engaged Buddhism in the West. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-841-2.

- Harvey, Peter (2010). "Buddhist Perspectives on Crime and Punishment". In Powers, John; Prebish, Charles S. (eds.). Destroying Mara Forever: Buddhist Ethics Essays in Honor of Damien Keown. Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 978-1-55939-788-9.

- Loy, David R. (2008). "Awareness Bound and Unbound: Realizing the Nature of Attention". Philosophy East and West. 58 (2): 230. JSTOR 20109462.

- Attwood, Jayarava (2014). "Escaping the Inescapable: Changes in Buddhist Karma". Journal of Buddhist Ethics. 21: 522. ISSN 1076-9005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2018.

- Kosuta 2017, p. 42.

- van Oosten 2008, pp. 252–3.

- Prüfung und Initiation im Buche Pausya und in der Biographie des Nāropa [Test and Initiation in the Book Pauṣya and in the Biography of Nāropa] (in German). Wiesbaden. 1965. p. 11.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 151.

- Gombrich 2006, pp. 144–51.

- Gombrich 2006, pp. 136, 141.

- Mudagamuwa & Von Rospatt 1998, p. 170.

- Gombrich 2006, pp. 155–62.

- Gombrich 2006, pp. 152–4.

- Brancaccio 1999, pp. 105–6.

- Mudagamuwa & Von Rospatt 1998, p. 177 n.25.

- Analayo 2008, pp. 143–4 n.42.

- Gombrich 2006, pp. 152 n.7, 155.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 152, 156.

- Mudagamuwa & Von Rospatt 1998, pp. 172–3.

- Malalasekera, G.P.; Weeraratne, W.G., eds. (2003). "Aṅgulimāla". Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. 1. Government of Sri Lanka. p. 628. OCLC 2863845613.

- Brancaccio 1999, pp. 112–4.

- Brancaccio 1999, pp. 115–6.

- Harvey 2013, p. 266.

- Jerryson, Michael (2013). "Buddhist Traditions and Violence". In Juergensmeyer, Mark; Kitts, Margo; Jerryson, Michael (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Violence. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-975999-6.

- Thompson 2017, p. 188.

- Wiltshire 1984, p. 95.

- Kangkanagme, Wickrama; Keerthirathne, Don (27 July 2016). "A Comparative Study of Punishment in Buddhist and Western Educational Psychology". The International Journal of Indian Psychology. 3 (4/57): 36. ISBN 9781365239939.

- Mathers 2013, p. 129.

- McDonald, Joseph (2017). "Introduction". In McDonald, Joseph (ed.). Exploring Moral Injury in Sacred Texts. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-78450-591-2.

- Thompson 2017, p. 182.

- Thompson 2017, p. 189.

- Loy 2009, p. 1247.

- Shrestha, Mathura P. (9 January 2007). "Human Rights including Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Theoretical and Philosophical Basis". Canada Foundation for Nepal. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- Horigan, D. P. (1 January 1996). "Of Compassion and Capital Punishment: A Buddhist Perspective on the Death Penalty". The American Journal of Jurisprudence. 41 (1): 282. doi:10.1093/ajj/41.1.271.

- Van Daele, W. (2013). "Fusing Worlds of Coconuts: The Regenerative Practice in Precarious Life-Sustenance and Fragile Relationality in Sri Lanka". The South Asianist. 2 (2): 100, 102–3. ISSN 2050-487X. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- Wilson 2016, p. 289.

- Wilson 2016, pp. 295–6.

- Thompson 2017, p. 184.

- Thompson 2017, pp. 185–6.

- Fernquest, Jon (13 April 2011). "Buddhism in UK prisons". Bangkok Post. Archived from the original on 2018-05-07. Retrieved 2 May 2018 – via Bangkok Post Learning.

- Harvey 2013, p. 450.

- "The Story of Angulimala". Angulimala, the Buddhist Prison Chaplaincy. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Parivudhiphongs, Alongkorn (9 April 2003). "Angulimala awaits fate". Asia Africa Intelligence Wire.

- "Plea against movie to go to Visanu". Asia Africa Intelligence Wire. 11 April 2003.

- Ngamkham, Wassayos (2 April 2003). "Movie based on Buddhist character needs new title". Bangkok Post. Archived from the original on 4 April 2003.

- "Buddhist groups want King to help impose ban on movie". Asia Africa Intelligence Wire. 9 April 2003.

- Ngamkham, Wassayos (10 April 2003). "Censors allow film to be shown". Asia Africa Intelligence Wire.

- Thompson 2017, p. 175 n.15.

- Thompson 2015, p. 168.

- Thompson 2015, p. 169.

- Thompson 2015, pp. 172–3.

- Der Pilger Kamanita: Ein Legendenroman by Karl Gjellerup in Project Gutenberg, chapters XXXIII. Angulimala, XXXV. Lautere Spende, XL. Im Krishnahain (German)

Bibliography

- Analayo, Bhikkhu (2008), "The Conversion of Angulimāla in the Saṃyukta-āgama", Buddhist Studies Review, 25 (2): 135–48, doi:10.1558/bsrv.v25i2.135

- Bareau, André (1986), "Etude du bouddhisme: Aspects du bouddhisme indien décrits par les pèlerins chinois (suite) II. La legende d'Angulimala dans les ancients textes canoniques" [Study of Buddhism: Aspects of Indian Buddhism as Described by the Chinese Pilgrims (continued), 2. The Legend of Angulimala in the Ancient Canonical Texts], Annuaire du Collège de France 1985–86 (in French) (86): 647–58, ISSN 0069-5580

- Barrett, Timothy H. (2004), "The Madness of Emperor Wuzong", Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie, 14 (1): 173–86, doi:10.3406/asie.2004.1206

- Brancaccio, Pia (1999), "Aṅgulimāla or the Taming of the Forest", East and West, 49 (1/4): 105–18, JSTOR 29757423

- Gombrich, Richard (2006) [1996], How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings (PDF) (2nd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-37123-6, lay summary – Angulimala and Tantric Buddhism (22 April 2011)

- Harvey, Peter (2013), An introduction to Buddhism: teachings, history and practices (PDF) (2nd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4

- Kosuta, M. (2017), "The Aṅgulimāla-Sutta: The Power of the Fourth Kamma", Journal of International Buddhist Studies, 8 (2): 35–47

- Loy, D.R. (2009), "A Different Enlightened Jurisprudence?" (PDF), Saint Louis University Law Journal, 54: 1239–56, archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2018, lay summary – Healing Justice: A Buddhist Perspective, in: The Spiritual Roots of Restorative Justice, pp.81–97 (2001)

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1960), Dictionary of Pāli Proper Names, 1, Delhi: Pali Text Society, OCLC 793535195

- Mathers, Dale (2013), "Stop Running", in Mathers, Dale; Miller, Melvin E.; Ando, Osamu (eds.), Self and No-Self Continuing the Dialogue Between Buddhism and Psychotherapy, Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, pp. 121–131, ISBN 978-1-317-72386-8

- Mudagamuwa, Maithrimurthi; Von Rospatt, Alexander (1998), "Review of How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings", Indo-Iranian Journal, 41 (2): 164–179, doi:10.1163/000000098124992646, JSTOR 24663383

- Thompson, John (3 January 2015), "Ahimsā and its Ambiguities: Reading the Story of Buddha and Aṅgulimāla", Open Theology, 1 (1): 160–74, doi:10.1515/opth-2015-0005

- Thompson, John (2017), "Buddhist Scripture and Moral Injury", in McDonald, Joseph (ed.), Exploring Moral Injury in Sacred Texts, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 169–90, ISBN 978-1-78450-591-2

- van Oosten, Karel (1 June 2008), "Kamma and Forgiveness with some Thoughts on Cambodia", Exchange, 37 (3): 237–62, doi:10.1163/157254308X311974

- Wilson, Liz (2016), "Murderer, Saint and Midwife", in Holdrege, Barbara A.; Pechilis, Karen (eds.), Refiguring the Body: Embodiment in South Asian Religions, SUNY Press, pp. 285–300, ISBN 978-1-4384-6315-5

- Wiltshire, M. G. (1984), Ascetic Figures before and in Early Buddhism (PDF), Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-009896-2, archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2018, retrieved 29 April 2018

- Zin, Monika (2005), Jarrige, Catherine; Levèfre, Vincent (eds.), The Unknown Ajanta Painting of the Aṅgulimāla Story, Proceedings of the sixteenth international conference of the European Association of South Asian Archaeologists: held in the Collège de France, Paris, 2–6 July 2001, 2, Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations, pp. 705–13, ISBN 2865383016, archived from the original on 7 May 2018, retrieved 30 April 2018

External links

- Theragāthā, canonical Pāli verses about Aṅgulimāla, translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

- Aṅgulimāla Sutta: About Aṅgulimāla, translated from the Pāli discourses by Thanissaro Bhikkhu

- 2003 film about Aṅgulimāla

- Angulimala: A Murderer's Road to Sainthood, written by Hellmuth Hecker, based on Pāli sources

- Angulimala, written by G.K. Ananda Kumarasiri