Vaccaei

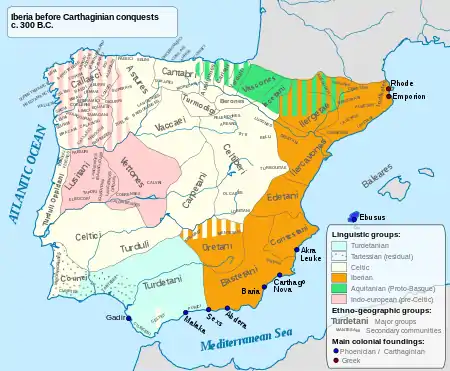

The Vaccaei or Vaccei were a pre-Roman Celtic[1] people of Spain, who inhabited the sedimentary plains of the central Duero valley, in the Meseta Central of northern Hispania (specifically in Castile and León).[2] Their capital was Intercatia in Paredes de Nava.

Origins

The Vaccaei were probably largely of Celtic descent and probably related to the Celtiberians.[2] Their name may be derived from the Celtic word vacos, meaning a slayer, since they were celebrated fighters. However, some scholars have reasoned that the name ‘Vaccaei’ may actually derive from ‘Aued-Ceia’, a contraction of Ceia, the presumed ancient name of the modern river Cea, prefixed by the Indo-European root *aued- (water).[3]

They often acted in concert with their neighbours, the Celtiberi, suggesting that they may have been part of the Celtiberian peoples.[2] They had a strict egalitarian society practising land reform and communal food distribution.[2] This society was part of an Hispano-Celtic substrate, which explains the cultural, socio-economic, linguistic and ideological affinity of the Vaccaei, Celtiberians, Vettones, Lusitani, Cantabri, Astures and Callaeci.[4][5][6] The Vaccean civilization was the result of a process of local evolution, importing elements from other cultures, whether by new additions of people or cultural and trading contacts with neighbouring groups. It is also believed that it was from the Vaccei that the warlike Arevaci stemmed from around the late 4th Century BC to conquer the eastern meseta.

Culture

Archeology has identified the Vaccei with the 2nd Iron Age ‘Douro Culture’ – which evolved from the previous early Iron Age ‘Soto de Medinilla’ (c. 800-400 BC) cultural complex of the middle Douro basin –, being also affiliated with the Turmodigi. This is confirmed by the stratigraphic study of their settlements, where have been found elements of the Vaccean culture on top of the remains of earlier cultures. For example, at Pintia (modern-day Padilla de Duero – Valladolid), there is evidence of continuous human settlement since Eneolithic times to the Iron Age, when the Vaccean period arose. The necropolis at Pintia is currently being excavated by an international field school students’ team every summer under the supervision of the University of Valladolid and the Federico Wattenberg Center of Vaccean Studies.

The Vaccei were considered the most cultivated people west of the Celtiberians, and were distinguishable by a special collectivist type social structure, which enabled them to exploit successfully the wheat- and grass-growing areas of the western plateau.[7]

Religion

Like the Arevaci, they also practiced the rite of excarnation by exposing the corpses of warriors slain in battle to the vultures, which were regarded as sacred animals, as described by Claudius Aelianus.[8]

Location

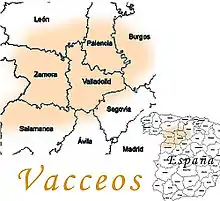

The Vaccean homeland extended throughout the center of the northern Meseta, along both banks of the Duero River. Their capital was Pallantia (either Palencia or Palenzuela) and Ptolemy[9] lists in their territory some twenty towns or Civitates, including Helmantica/Salmantica (Salamanca), Arbucala (Toro), Pincia or Pintia (Padilla de Duero – Valladolid), Intercatia (Paredes de Nava – Palencia), Cauca (Coca – Segovia), Septimanca (Simancas), Rauda (Roa), Dessobriga (Oserna) and Autraca or Austraca – located at the banks of the river Autra (Odra), seized from the Autrigones in the late 4th century BC – to name but a few. Although its borders are difficult to define, and shifted from time to time, it can be said to have occupied all of the province of Valladolid, and parts of León, Palencia, Burgos, Segovia, Salamanca and Zamora. By the time of the arrival of the Romans, the Cea and Esla rivers separated the Vaccaei from the Astures in the northwest, while a line traced between the Esla and the Pisuerga rivers was the border with the Cantabri. To the east, the Pisuerga and Arlanza rivers marked the frontier with the Turmodigi, and a little farther south, the Arevaci were their neighbors and allies. On the south and southeast lay the Vettones in an area that roughly corresponds to the distribution of verracos around the highlands of Ávila and Salamanca and Aliste (Zamora), between them and the Lusitanians. It is likely that there was some contact with the latter to the west of Zamora.

History

Traditionally aggressive, the Vaccei were far from being the “harmless and submissive nation” portrayed by Paulus Orosius.[10] They participated in the 5th century BC Celtici migrations alongside off-shots of the Arevaci and Lusones to settle in the west and southwest regions of the Iberian Peninsula. In the early 3rd Century BC they aided the smaller Turmodigi people in their liberation from the rule of the Autrigones. The Vaccei enter the historical record around the late 3rd century BC, when in 221-220 BC they allied themselves with the Carpetani and Olcades to thwart Hannibal’s offensive into their respective territories, but they were defeated after the fall of Salmantica and Arbucala to the Carthaginians.[11][12] The Vaccei appear to have taken no part in the 2nd Punic War, though in 193-192 BC they joined the combined force of Carpetani, Vettones, and Celtiberians that was defeated by Consul Marcus Fulvius at the battle of Toletum.[13] Alongside the Lusitani, they were again beaten by the Praetor of Hispania Ulterior Lucius Postumius Albinus during its first incursion into the central Meseta in 179 BC.[14]

Allies of the Arevaci during the Celtiberian Wars, the Vaccei assumed a more important role by supporting their neighbors, despite being subjected to the punitive campaigns carried out by the Roman Consul Lucius Licinius Luculus (151-150 BC),[15] Proconsul Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus in 142 BC,[16] and Consuls Marcus Popilius Laenas (139-138 BC)[17] and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Porcina in 137 BC.[18][19][20] After the destruction of Numantia in 134-133 BC, the Vaccei were technically submitted and included into Hispania Citerior province; however, during the Sertorian Wars they lent their support to Quintus Sertorius, with several Vacceian towns remaining loyal to his cause even after his death. In 76 BC, Sertorius’ sent one of its cavalry commanders, Gaius Insteius, to the Vacceian country in search of remounts for its battered mounted troops.[21] The backlash came in 74 BC when Proconsul Pompey besieged the vacceian capital Pallantia, setting on fire its adobe brick walls[22][23] and stormed Cauca.[24] Defeated in 73 BC by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius and Pompey, the Vaccei rose again in 57-56 BC in a joint uprising with the Turmodigi and northern Celtiberians, only to be crushed by the Praetor of Citerior Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos Iunior.[25] Pressured by Astures' and Cantabri raids, the Vaccei rebelled a last time in 29 BC, just prior to the Astur-Cantabrian wars, only to be subdued by Consul Titus Statilius Taurus.

Romanization

The Vaccei were later aggregated to the new Hispania Terraconensis province created in 27 BC by Emperor Augustus.

Namesake

The Basques came to be called mistakenly Vaccaei and Vacceti by several early medieval chronicles and authors.

See also

Notes

- Cremin, The Celts in Europe (1992), p. 57.

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (2002). The Celts: A History. Cork: Collins Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-85115-923-0.

- Martino, Roma contra Cantabros y Astures – Nueva lectura de las fuentes (1982), p. 18, footnote 14.

- Almagro-Gorbea, Martín; Alberto J. Lorrio (2004). "War and Society in the Celtiberian World". Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 481. ISBN 9781851094400.

- Cólera, Carlos Jordán (March 16, 2007). "The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula:Celtiberian" (PDF). E-Keltoi. 6: 749–750. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliothekes Istorikes, V: 34, 3.

- Claudius Aelianus, Varia Historia, X, 22.

- Ptolemy, Geographia, II, 5, 6

- Paulus Orosius, Historiarum adversus Paganus, 5, 5.

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 21: 5.

- Polybius, Istorion, 3, 13.

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 37: 7, 6.

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 40: 35, 39, 44, 47-50.

- Appian, Romaika, 6, 51-52; 54.

- Appian, Iberiké 76.

- Appian, Romaika, 17, 79.

- Appian, Romaika, 6, 81-83.

- Livy, Periochae, 56: 1-2.

- Paulus Orosius, Historiarum adversus Paganus, 5, 5.

- Livy, Fragmenta Librii, 91.

- Appian, Romaika, 1, 112.

- Matyszak, Sertorius and the struggle for Spain (2013), p. 145.

- Frontinus, Stratagemata, II, 11, 2.

- Cassius Dio, Romaïké istoría, 39, 54.

Bibliography

- Blanco, António Bellido, Sobre la escritura entre los Vacceos, in ZEPHYRUS – revista de prehistoria y arqueologia, vol. LXIX, Enero-Junio 2012, Ediciones Universidad Salamanca, pp. 129–147. ISSN 0514-7336

- Collins, Roger, The Vaccaei, the Vaceti, and the rise of Vasconia, Studia Historica VI. Salamanca, 1988. Reprinted in Roger Collins, Law, Culture and Regionalism in Early Medieval Spain. Variorum (1992). ISBN 0-86078-308-1.

- Cremin, Aedeen, The Celts in Europe, Sydney, Australia: Sydney Series in Celtic Studies 2, Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Sydney (1992) ISBN 0-86758-624-9.

- Alvarado, Alberto Lorrio J., Los Celtíberos, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Murcia (1997) ISBN 84-7908-335-2

- Duque, Ángel Montenegro et alli, Historia de España 2 – colonizaciones y formacion de los pueblos prerromanos, Editorial Gredos, Madrid (1989) ISBN 84-249-1013-3

- González-Cobos, A.M., Los Vacceos – Estudio sobre los pobladores del valle medio del Duero durante la penetración romana, Universidad Pontificia, Salamanca (1989)

- Motoza, Francisco Burillo, Los Celtíberos – Etnias y Estados, Crítica, Grijalbo Mondadori, S.A., Barcelona (1998, revised edition 2007) ISBN 84-7423-891-9

- Leonard A Curchin (5 May 2004). The Romanization of Central Spain: Complexity, Diversity and Change in a Provincial Hinterland. Routledge. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-134-45112-8.

- Philip Matyszak, Sertorius and the struggle for Spain, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley (2013) ISBN 978-1-84884-787-3

Further reading

- Almagro-Gorbea, Martín, Les Celtes dans la péninsule Ibérique, in Les Celtes, Éditions Stock, Paris (1997) ISBN 2-234-04844-3

- Berrocal-Rangel, Luis, Los pueblos célticos del soroeste de la Península Ibérica, Editorial Complutense, Madrid (1992) ISBN 84-7491-447-7

- Berrocal-Rangel, Luis & Gardes, Philippe, Entre celtas e íberos, Fundación Casa de Velázquez, Madrid (2001)

- Martino, Eutimio, Roma contra Cantabros y Astures – Nueva lectura de las fuentes, Breviarios de la Calle del Pez n. º 33, Diputación provincial de León/Editorial Eal Terrae, Santander (1982) ISBN 84-87081-93-2

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí, The Celts: A History, The Collins Press, Cork (2002) ISBN 0-85115-923-0

- Koch, John T.(ed.), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO Inc., Santa Barbara, California (2006) ISBN 1-85109-440-7, 1-85109-445-8

- Zapatero, Gonzalo Ruiz et alli, Los Celtas: Hispania y Europa, dirigido por Martín Almagro-Gorbea, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Editorial ACTAS, S.l., Madrid (1993)

External links

- Detailed map of the Pre-Roman Peoples of Iberia (around 200 BC)

- Álvarez-Sanchís, Jesús R. (2005), "Oppida and Celtic society in western Spain". e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies 6: 255-285

- http://www.celtiberia.net