Cantabri

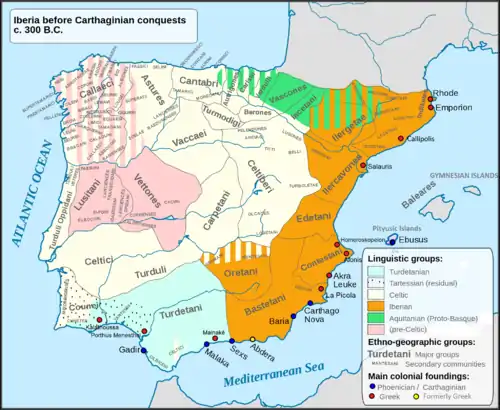

The Cantabri (Greek: Καντάβροι, Kantabroi) or Ancient Cantabrians, were a pre-Roman people, probably Celtic or pre-Celtic European, and large tribal federation that lived in the northern coastal region of ancient Iberia in the second half of the first millennium BC. These peoples and their territories were incorporated into the Roman Province of Hispania Tarraconensis in the year 19 BC, following the Cantabrian Wars.

Name

Cantabri is a Latinized form of a local name, presumably meaning "Highlanders" and deriving from the reconstructed root *cant- ("mountain") in Ancient Ligurian.[1]

Geography

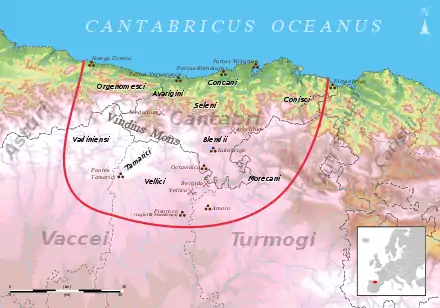

Cantabria, the land of the Cantabri, originally comprised much of the highlands of the northern Spanish Atlantic coast,[2] including the whole of modern Cantabria province, eastern Asturias, nearby mountainous regions of Castile and León, the northern of province of Palencia and province of Burgos and northeast of province of León. Following the Roman conquest, this area was, however, much reduced, making up only Cantabria and eastern Asturias.[3]

History

Origins

The ancestors of the Cantabri were thought by the Romans to have migrated to the Iberian Peninsula around the 4th Century BC,[4][5] and were said by them to be more mixed than most peninsular Celtic peoples, their eleven or so tribes, assessed by Roman writers according to their names, were supposed to have included Gallic, Celtiberian, Indo-Aryan, Aquitanian, and Ligurian origins.

A detailed analysis of place-names in ancient Cantabria shows a strong Celtic element along with an almost equally strong "Para-Celtic" element (both Indo-European) and thus disproves the idea of a substantial pre-Indo-European or Basque presence in the region.[6] This supports the earlier view that Untermann considered the most plausible, coinciding with archaeological evidence put forward by Ruiz-Gálvez in 1998,[7] that the Celtic settlement of the Iberian Peninsula was made by people who arrived via the Atlantic Ocean in an area between Brittany and the mouth of the River Garonne, finally settling along the Galician and Cantabrian coast.[8]

Early history

Regarded as savage and untamable mountaineers, the Cantabri long defied the Roman legions and made a name for themselves for their independent spirit and freedom.[2] Indeed, Cantabri warriors were regarded as being tough and fiercest fighters,[9] suitable for mercenary employment,[10] but prone to banditry.[11] The earliest references to them are found in the texts of ancient historians such as Livy[12] and Polybius,[13] who mention Cantabrian mercenaries in Carthaginian service fighting at the Battle of the Metaurus in 207 BC, and Silius,[14] who talks about a chieftain named Larus recruited by Mago and a Cantabrian contingent in Hannibal's army. Another author, Cornelius Nepos,[15] claims that the Cantabrian tribes first submitted to Rome upon Cato the Elder’s campaigns in Celtiberia in 195 BC.[16] In any case, such was their reputation that when a battered Roman army under consul Gaius Hostilius Mancinus was besieging Numantia in 137 BC, the rumor of the approach of a large combined Cantabri-Vaccaei relief force was enough to cause the rout of 20,000 panic-stricken Roman legionaries, forcing Mancinus to surrender under humiliating peace terms.[17][18]

By the 1st century BC they comprised eleven or so tribes—Avarigines, Blendii, Camarici or Tamarici, Concani, Coniaci or Conisci, Morecani, Noegi, Orgenomesci, Plentuisii, Salaeni, Vadinienses, and Vellici or Velliques—gathered into a tribal confederacy with the town of Aracillum (Castro de Espina del Gallego, Sierra del Escudo – Cantabria), located at the strategic Besaya river valley, as their political seat. Other important Cantabrian strongholds included Villeca/Vellica (Monte Cildá – Palencia), Bergida (Castro de Monte Bernorio – Palencia) and Amaya/Amaia (Peña Amaya – Burgos). In early 1st century BC, the Cantabri began to play a double game by lending their services to individual Roman generals on occasion but, at same time, supported rebellions within Roman Spanish provinces and carried out raids in times of unrest. This opportunistic policy led them to side with Pompey during the final phase of the Sertorian Wars (82–72 BC), and they continued to follow the Pompeian cause until the defeat of his generals Afranius and Petreius at the battle of Ilerda (Lérida) in 49 BC.[19][20] Prior to that, the Cantabri had unsuccessfully intervened in the Gallic Wars by sending in 56 BC an army to help the Aquitani tribes of south-eastern Gaul against Publius Crassus, the son of Marcus Crassus serving under Julius Caesar.[21]

Under the leadership of the chieftain Corocotta, the Cantabri’s own predatory raids on the Vaccaei, Turmodigi and Autrigones[22] whose rich territories they coveted, according to Florus,[23] coupled with their backing of a Vaccaei anti-Roman revolt in 29 BC, ultimately led to the outbreak of the First Cantabrian Wars, which resulted in their conquest and partial annihilation by Emperor Augustus.[24] The remaining Cantabrian population and their tribal lands were absorbed into the newly created Transduriana Province.

Nevertheless, the harsh measures devised by Augustus and implemented by his general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa to pacify the province in the aftermath of the campaign only contributed to further instability in Cantabria. Near-constant tribal uprisings (including a serious slave revolt in 20 BC that quickly spread to neighboring Asturias)[25] and guerrilla warfare continued to plague the Cantabrian lands until the early 1st century AD, when the region was granted a form of local self-rule upon being included in the new Hispania Tarraconensis province.

Romanization

Although the Romans founded colonies and established military garrisons at Castra Legio Pisoraca (camp of Legio IIII Macedonica – Palencia), Octaviolca (near Valdeolea – Cantabria) and Iuliobriga (Retortillo – Reinosa), Cantabria never became fully romanized and its people preserved many aspects of Celtic language, religion and culture well into the Roman period. The Cantabri did not lose their warrior skills either, providing auxiliary troops (Auxilia) to the Roman Imperial army for decades and these troops participated in Emperor Claudius' invasion of Britain in AD 43–60.

Early Middle Ages

The Cantabri re-emerged,[26] as did their neighbors the Astures, amid the chaos of the Migration Period of the late 4th century. Thenceforward the Cantabri started to be Christianized and were violently crushed by the Visigoths in the 6th century.[27] However, Cantabria and the Cantabri are heard of many decades later in the context of the Visigoth wars against the Vascones (late 7th century).[28] They only became fully Latinized in their language and culture after the Muslim Conquest of Iberia in the 8th century.

Culture

According to Pliny the Elder[29] Cantabria also contained gold, silver, tin, lead and iron mines, as well as magnetite and amber, but little is known about them; Strabo[30] also mentions salt extraction in mines, such as the ones existent around Cabezón de la Sal. One of his most famous and strange customs was the couvade, when, after the birth of a child, the mother had to get up and the father go to bed, to be cared for by the mother.

Religion

Literary and epigraphic evidence confirms that, like their Gallaeci and Astures neighbors, the Cantabri were polytheistic, worshipping a vast and complex pantheon of male and female Indo-European deities in sacred oak or pine woods, mountains, water-courses and small rural sanctuaries.

Druidism does not appear to have been practiced by the Cantabri, though there is enough evidence for the existence of an organized priestly class who performed elaborated rites, which included ritual steam baths, festive dances, oracles, divination, human and animal sacrifices. In this respect, Strabo[31] mentions that the peoples of the north-west sacrificed horses to an unnamed God of War, and both Horace[32] and Silius Italicus[33] added that the Concani had the custom of drinking the horse’s blood at the ceremony.

Notes

- Martino (1982), Roma contra Cantabros y Astures, p. 18

- EB (1911).

- EB (1878).

- Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, III, 29.

- Strabo, Geographikon, III, 4, 12.

- Curchin, Leonard A. (2007). "Linguistic Strata in Ancient Cantabria: the evidence of toponyms". Hispania Antiqua. XXXI-2007: 7–20.

- Ruiz-Gálvez Priego, Luisa (1998). La Europa Atlántica en la Edad del Bronce. Un viaje a las raíces de la Europa occidental. Barcelona: Ed. Crítica.

- Burillo Mozota, Francisco (2005). "Celtiberians: Problems and Debates". Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. The Celtic in the Iberian Peninsula. 6: 13. Archived from the original on 2018-04-10. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- Florus, Epitomae Historiae Romanae, II, 33, 46-47.

- Silius Italicus, Punica, V, 192.

- Strabo, Geographikon, III, 3, 8.

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita, 27: 43-49.

- Polybius, Istorion, 11: 1-3.

- Silius Italicus, Punica, 3

- Cornelius Nepos, De Viris Illustribus, 47.

- Though most modern historians have cast serious doubts upon the veracity of this particular episode, since other sources (Livy, Appian, Polybius) don’t mention it at all.

- Plutarch, Tiberius Gracchus, 5, 4.

- Appian, Romaika, 83.

- Caesar, De Bello Civili, I: 43-46.

- Lucan, Pharsalia, IV: 8-10.

- Caesar, De Bello Gallico, 3, 23.

- Paulus Orosius, Historiarum Adversus Paganus, 6: 21, 1.

- Florus, Epitomae Historiae Romanae, 2: 33, 46.

- Suetonius, Augustus, 21. - Tiberius saw his first military experience in the campaign against the Cantabri of 25 BC, as a tribune of the soldiers. Tiberius, 9.

- Cassius Dio, Romaiké Historia, 54: 11, 1.

- Collins (1990), p. 92.

- Collins (1983), pp. 106-107.

- Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0631175652., p. 114.

- Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, 34, 112; 149; 158.

- Strabo, Geographikon, III, 3, 7.

- Strabo, Geographikon, III, 3, 7.

- Horace, Odes, III, 4, 35

- Silius Italicus, Hispania, III, 3, 161.

References

- Almagro-Gorbea, Martín (1997). "Les Celtes dans la péninsule Ibérique". Les Celtes. Paris: Éditions Stock. ISBN 2-234-04844-3.

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 27

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopædia Britannica, 5 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 207

- Collins, Roger (1990). The Basques (2nd ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0631175652.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Roger (1983). Early Medieval Spain. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22464-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eutimio Martino, Roma contra Cantabros y Astures – Nueva lectura de las fuentes, Breviarios de la Calle del Pez n. º 33, Diputación provincial de León/Editorial Eal Terrae, Santander (1982) ISBN 84-87081-93-2

- Lorrio, Alberto J., Los Celtíberos, Editorial Complutense, Alicante (1997) ISBN 84-7908-335-2

- Martín Almagro Gorbea, José María Blázquez Martínez, Michel Reddé, Joaquín González Echegaray, José Luis Ramírez Sádaba, and Eduardo José Peralta Labrador (coord.), Las Guerras Cántabras, Fundación Marcelino Botín, Santander (1999) ISBN 84-87678-81-5

- Montenegro Duque, Ángel et alii, Historia de España 2 – colonizaciones y formacion de los pueblos prerromanos, Editorial Gredos, Madrid (1989) ISBN 84-249-1013-3

- Burillo Mozota, Francisco, Los Celtíberos – Etnias y Estados, Crítica, Grijalbo Mondadori, S.A., Barcelona (1998, revised edition 2007) ISBN 84-7423-891-9

- Kruta, Venceslas, Les Celtes, Histoire et Dictionnaire: Des origines à la Romanization et au Christianisme, Éditions Robert Laffont, Paris (2000) ISBN 2-7028-6261-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cantabri. |