Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, commonly referred to as the 1994 Crime Bill,[1] the Clinton Crime Bill,[2] or the Biden Crime Law,[3] is an Act of Congress dealing with crime and law enforcement; it became law in 1994. It is the largest crime bill in the history of the United States and consisted of 356 pages that provided for 100,000 new peace officers, $9.7 billion in funding for prisons and $6.1 billion in funding for prevention programs, which were designed with significant input from experienced police officers.[4] Sponsored by U.S. Representative Jack Brooks of Texas,[5] the bill was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Bill Clinton.[6] Then-Senator Joe Biden of Delaware drafted the Senate version of the legislation in cooperation with the National Association of Police Organizations, also incorporating the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) with Senator Orrin Hatch.[7][8]

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An Act to Control and Prevent Crime |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | 1994 Crime Bill, Clinton Crime Bill, Biden Crime Law |

| Enacted by | the 103rd United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 103–322 |

| Statutes at Large | 108 Stat. 1796 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 12 U.S.C.: Banks and Banking

18 U.S.C.: Crimes and Criminal Procedure 42 U.S.C.: Public Health and Social Welfare |

| U.S.C. sections created | 42 U.S.C. ch. 136 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

Following the 101 California Street shooting, the 1993 Waco Siege, and other high-profile instances of violent crime, the Act expanded federal law in several ways. One of the most noted sections was the Federal Assault Weapons Ban. Other parts of the Act provided for a greatly expanded federal death penalty, new classes of individuals banned from possessing firearms, and a variety of new crimes defined in statutes relating to hate crimes, sex crimes, and gang-related crime. The bill also required states to establish registries for sexual offenders by September 1997.

Origins

During the 1992 presidential campaign, Bill Clinton sought to reposition the Democratic Party, which had previously been attacked as "soft on crime," as an advocate for "get-tough" policing strategies as well as investing in community policing. Federal funding for additional police and community policing were both priorities of the Democratic Leadership Council, of which Clinton was a member.[9] In an announcement that the New York Times described as "a page from the Republican playbook," Clinton said on July 23, 1992:

We cannot take our country back until we take our neighborhoods back. Four years ago this crime issue was used to divide America. I want to use it to unite America. I want to be tough on crime and good for civil rights. You can't have civil justice without order and safety.[10]

Clinton's platform, Putting People First, proposed to:

Fight crime by putting 100,000 new police officers on the streets. We will create a National Police Corps and offer unemployed veterans and active military personnel a chance to become law enforcement officers at home. We will also expand community policing, fund more drug treatment, and establish community boot camps to discipline first-time non-violent offenders.[11]

The 135,000-member National Association of Police Officers endorsed Clinton for president in August 1992.[12]

Senator Joe Biden drafted the Senate version of the legislation in cooperation with National Association of Police Officers president Tom Scotto. According to the Washington Post, Biden later described their involvement: “You guys sat at that conference table of mine for a six-month period, and you wrote the bill.”[7]

Provisions

Federal Assault Weapons Ban

Title XI-Firearms, Subtitle A-Assault Weapons, formally known as the Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act but commonly known as the Federal Assault Weapons Ban or the Semi-Automatic Firearms Ban, barred the manufacture of 19 specific semi-automatic firearms, classified as "assault weapons", as well as any semi-automatic rifle, pistol, or shotgun capable of accepting a detachable magazine that has two or more features considered characteristic of such weapons. The list of such features included telescoping or folding stocks, pistol grips, flash suppressors, grenade launchers, and bayonet lugs.[13]

This law also banned possession of newly manufactured magazines holding more than ten rounds of ammunition.

The ban took effect September 13, 1994 and expired on September 13, 2004 by a sunset provision. Since the expiration date, there is no federal ban on the subject firearms or magazines capable of holding more than ten rounds of ammunition.

Federal Death Penalty Act

Title VI, the Federal Death Penalty Act, created 60 new death penalty offenses under 41 federal capital statutes,[14] for crimes related to acts of terrorism, non-homicidal narcotics offenses, murder of a federal law enforcement officer, civil rights-related murders, drive-by shootings resulting in death, the use of weapons of mass destruction resulting in death, and carjackings resulting in death.

The 1995 Oklahoma City bombing occurred a few months after this law came into effect, and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 was passed in response, which further increased the federal death penalty. In 2001, Timothy McVeigh was executed for the murder of eight federal law enforcement agents under that title.

Elimination of higher education for inmates

One of the more controversial provisions of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act overturned a section of the Higher Education Act of 1965 permitting prison inmates to receive a Pell Grant for higher education while they were incarcerated. The amendment is as follows:

(a) IN GENERAL- Section 401(b)(8) of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (20 U.S.C. 1070a(b)(8)) is amended to read as follows: (8) No basic grant shall be awarded under this subpart to any individual who is incarcerated in any Federal or State penal institution.[15]

The VCCLEA effectively eliminated the ability of lower-income prison inmates to receive college educations during their term of imprisonment, thus ensuring the education level of most inmates remains unimproved over the period of their incarceration.[16]

There is growing advocacy for reinstating Pell Grant funding for all prisoners who would qualify despite their incarceration status.[17] Perhaps the most prominent statement has come from Donna Edwards along with several other members of the House of Representatives, who introduced the Restoring Education and Learning Act (REAL Act) in the spring of 2013. At the executive level, the Obama administration backed a program under development at the Department of Education to allow for a limited lifting of the ban for some prisoners, called the Second Chance Pell Pilot.[18] SpearIt has argued, "First, there are genuine penal and public benefits that derive from educating prisoners. Second, and perhaps more critically, revoking Pell funding fails to advance any of the stated purposes of punishment. In the decades since the VCCLEA's enactment, there is little indication that removing prisoners from Pell eligibility has produced tangible benefits; on the contrary, among other unfavorable outcomes, disqualifying prisoners may reduce public safety and exact severe social and financial costs."[19]

Violence Against Women Act

Title IV, the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), allocated $1.6 billion to help prevent and investigate violence against women. VAWA was renewed in 2000, 2005, and 2013. This includes:

- The Safe Streets for Women Act, which increased federal penalties for repeat sex offenders and requires mandatory restitution for the medical and legal costs of sex crimes.

- The Safe Homes for Women Act increased federal grants for battered women's shelters, created a National Domestic Violence Hotline, and required for restraining orders of one state to be enforced by the other states. It also added a rape shield law to the Federal Rules of Evidence.

Part of VAWA was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in United States v. Morrison (2000).

Driver's Privacy Protection Act

Title XXX, the Driver's Privacy Protection Act, governs the privacy and disclosure of personal information gathered by the states' Departments of Motor Vehicles. The law was passed in 1994; it was introduced by Jim Moran in 1992 after an increase in opponents of abortion rights using public driving license databases to track down and harass abortion providers and patients, most notably by both besieging Susan Wicklund's home for a month and following her daughter to school.[20]

Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act

Under Title XVII,[21] known as the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act, guidelines were established for states to track sex offenders.[22] States had also been required to track sex offenders by confirming their place of residence annually for ten years after their release into the community or quarterly for the rest of their lives if the sex offender was convicted of a violent sex crime.[22] The Wetterling Act was later amended in 1996 with Megan's Law, which permanently required states to give public disclosure of sex offenders.[22] In 2006, the Wetterling Act's state registers was replaced with a federal register through the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act.[23]

Community Oriented Policing Services

Since 1994, the COPS Office has provided $30 billion in assistance to state and local law enforcement agencies to help hire community policing officers. The COPS Office also funds the research and development of guides, tools and training, and provides technical assistance to police departments implementing community policing principles.[24] The law authorized the COPS Office to hire 100,000 more police officers to patrol the nation's streets.[25]

Violent Offender Incarceration and Truth-in-Sentencing Incentive Grants Program

Title II of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 provided incentive grants to build and expand correctional facilities to qualifying states that enforced mandatory sentencing of 85% of a person's sentence conviction. [26] [27] "One purpose of theVOI/TIS incentive grants," the Bureau reported, "is to enable States to manage prison capacity by providing funds to increase prison beds for violent offenders."[28]

Other provisions

The Act authorized the initiation of "boot camps" for delinquent minors and allocated a substantial amount of money to build new prisons.

Fifty new federal offenses were added, including provisions making membership in gangs a crime. Some argued that these provisions violated the guarantee of freedom of association in the Bill of Rights. The Act did incorporate elements of H.R. 50 "Federal Bureau of Investigation First Amendment Protection Act of 1993" (into §2339A (c)) to prohibit investigations based purely on protected First Amendment activity, but this was effectively removed in the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996.[29]

The Act also generally prohibits individuals who have been convicted of a felony involving breach of trust from working in the business of insurance, unless they have received written consent from state regulators.

The Act also made drug testing mandatory for those serving on federal supervised release.

The Act prohibits "any person acting on behalf of a governmental authority, to engage in a pattern or practice ... that deprives persons of rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States." (Title XXI, Subtitle D.) Subtitle D further requires the United States Department of Justice to issue an annual report on "the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers." Such reports have not been issued, however.[30]

The Act included a three-strikes provision addressing repeat offenders.[31]

The Act expanded the scope of required FBI data to include hate crimes based on disability, and the FBI began collecting data on disability bias crimes on January 1, 1997.[32]

Legacy and impacts

The 1994 Crime Bill marked a shift in the politics of crime and policing in the United States. Sociologist and criminologist William R. Kelly states that, "While the longer-term impact of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 was questionable, the political impact was clear — crime control or 'tough on crime' became a bipartisan issue."[33]

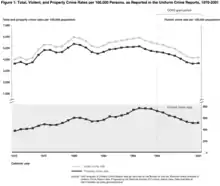

Bill Clinton has claimed credit for the reduction in crime rates in the 1990s, stating that, "Because of that bill we had a 25-year low in crime, a 33-year low in the murder rate, and because of that and the background-check law, we had a 46-year low in deaths of people by gun violence.”[34] Crime rates underwent a long period of reduction in beginning in 1991 and declined by 26% during this eight-year period.[25][35] The primary reasons for this reduction remain a topic of debate.[25] A study by the General Accounting Office found that grant funding from the Community Oriented Policing Services program supported the hiring of an estimated 17,000 additional officers in 2000, its peak year of impact, and increased additional employment by 89,000 officer-years from 1994 to 2001. This was an increase of 3% in the number of sworn officers in the United States.[36] The GAO concluded that the COPS Office potentially had a modest impact in reducing crime, contributing to an approximate 5% reduction in overall crime rates from 1993 to 2001.[35] A published study by criminologists John Worrell and Tomislav Kovandzic found that "COPS spending had little to no effect on crime."[37]

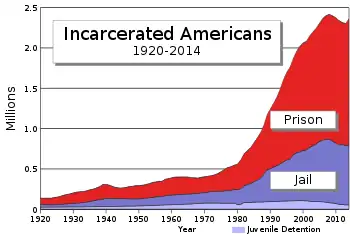

The Crime Bill has also become emblematic of a shift towards mass incarceration in the United States, although its contribution to the long-term trend of expanding prisons is debated. The Justice Policy Institute stated in 2008 that "the Clinton Administration's 'tough on crime' policies resulted in the largest increases in federal and state inmate populations of any president in American history".[38] Jeremy Travis, former director of the National Institute of Justice, described the truth-in-sentencing provisions of the law as a catalyst: "Here's the federal government coming in and saying we'll give you money if you punish people more severely, and 28 states and the District of Columbia followed the money and enacted stricter sentencing laws for violent offenses."[39] The Act may have had a minor effect on mass incarceration and prison expansion.[40] In 1998, twenty-seven states and the District of Columbia qualified for that Federal grant program.[26] Thirteen more states adopted truth-in-sentencing law applying to some crimes or with a lower percentage threshold.[28] By 1997, sixty-nine percent of sentenced violent offenders were in states meeting the 85% "truth-in-sentencing" threshold and over ninety percent faced at least a 50% threshold.[28] The Bureau of Justice Statistics projected in 1999 that, "As a result of truth-in-sentencing practices, the State prison population is expected to increase through the incarceration of more offenders for longer periods of time," and found that the State prison population had "increased by 57%" to "a high of 1,075,052 inmates" while the number of people sentenced to prison each year was only up by 17%.[28] However, a GAO report found that federal incentives were "not a factor" in enacting truth in sentencing provisions in 12 of the 27 states that qualified, and "a key factor" in just four.[41]

The legal system relied on plea bargains to minimize the increased case load.[42] Jerry Brown and Bill Clinton later expressed regret over the portions of the measure that led to increased prison population like the three strikes provision.[31][43]

See also

References

- Kessler, Glenn (May 16, 2019). "Joe Biden's defense of the 1994 crime bill's role in mass incarcerations". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- Lussenhop, Jessica (April 18, 2016). "Why is Clinton crime bill so controversial?". BBC News. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- Fifield, Anna (January 4, 2013). "Biden faces key role in second term". Financial Times. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- "Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994". National criminal justice reference service.

- Brooks, Jack B. (September 13, 1994). "H.R.3355 - 103rd Congress (1993-1994): Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994". U.S. Congress. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- "The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994". History, Art & Archives. US House of Representatives. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Kranish, Michael (June 8, 2020). "Joe Biden let police groups write his crime bill. Now, his agenda has changed". Washington Post. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Law, Tara (September 12, 2019). "The Violence Against Women Act Was Signed 25 Years Ago. Here's How the Law Changed American Culture". Time. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- From, Al (December 3, 2013). The New Democrats and the Return to Power. St. Martin's Publishing Group. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-137-40144-1.

- Ifill, Gwen (July 24, 1992). "THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: The Democrats; Clinton, in Houston Speech, Assails Bush on Crime Issue". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Clinton, Bill (June 21, 1992). "PUTTING PEOPLE FIRST: A NATIONAL ECONOMIC STRATEGY FOR AMERICA".

- Ifill, Gwen (August 21, 1992). "THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: THE DEMOCRATS; Clinton Needles Bush, Trying to Quiet His Thunder". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Spitzer, Robert J. (2012). "Assault Weapons". In Carter, Gregg Lee (ed.). Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 53. ISBN 978-0313386701.

- "The Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994". Office of the United States Attorneys. Department of Justice. Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- "H. R. 1168". Bulk.Resource.Org.

- "Education as Crime Prevention: The Case for Reinstating Pell Grant Eligibility for the Incarcerated" (PDF). Bard Prison Initiative. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2007.

- SpearIt (August 7, 2017). "Uncertainty Ahead: Pell Grant Funding for Prisoners". SSRN 3014983. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "A Second Chance for an Education". U.S. Department of Education. June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- SpearIt (February 18, 2016). "Keeping it REAL: Why Congress Must Act to Restore Pell Grant Funding For Prisoners". University of Massachusetts Law Review. 11 (1). SSRN 2711979.

- Miller, Michael W. (August 25, 1992). "Information Age: Debate Mounts Over Disclosure Of Driver Data". Wall Street Journal.

- "42 U.S. Code § 14071 to 14073 - Repealed. Pub. L. 109–248, title I, § 129(a), July 27, 2006, 120 Stat. 600". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- "Legislative History - SMART Office". SMART website - Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking (SMART).

- http://www.smart.gov/pdfs/practitioner_guide_awa.pdf

- "COPS History". Community Oriented Policing Services.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/fact-checker/wp/2014/09/26/bill-clintons-claim-that-100000-cops-sent-the-crime-rate-way-down/

- 103rd Congress (1993-1994). "H.R.3355 - Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994". congress.gov. congress.gov. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. "Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Truth in Sentencing in State Prisons" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Bureau of Justice Statistics. p. 3. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (January 1999). Truth in Sentencing in State Prisons (PDF) (Report). NCJ 170032. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Dempsey, James; Cole, David (2006). Terrorism and the Constitution: Sacrificing Civil Liberties In The Name Of National Security (Scribd Online ed.). New York: New Press. p. 63. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- Serpico, Frank (October 23, 2014). "The Police Are Still Out of Control". Politico Magazine: 2. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- Vara, Vauhini (November 7, 2014). "Will California Again Lead the Way on Prison Reform?". The New Yorker. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- "Hate crime statistics 1996" (PDF). CJIS. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 9, 2007. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- Kelly, William R. (2015). Criminal Justice at the Crossroads: Transforming Crime and Punishment. Columbia University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-231-53922-7.

- Terruso, Julia; Lubrano, Alfred (April 7, 2016). "Bill Clinton stumps for Hillary in Philly - and parries with protesters". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Ekstrand, Laurie E.; Kingsbury, Nancy R. (March 2006). Community Policing Grants: Cops Grants Were a Modest Contributor to Declines in Crime in The 1990s. DIANE Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4223-0454-9.

- Ekstrand, Laurie E.; Kingsbury, Nancy R. (March 2006). Community Policing Grants: Cops Grants Were a Modest Contributor to Declines in Crime in The 1990s. DIANE Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4223-0454-9.

- Worrall, John L.; Kovandzic, Tomislav V. (February 2007). "COPS grants and crime revisited". Criminology. 45 (1): 159–190. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00075.x.

- "Clinton Crime Agenda Ignores Proven Methods for Reducing Crime" (Press release). Justice Policy Institute. April 14, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- "20 Years Later, Parts Of Major Crime Bill Viewed As Terrible Mistake". NPR.org. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- "The controversial 1994 crime law that Joe Biden helped write, explained". Vox. June 20, 2019.

- US General Accounting Office (1998). Truth in Sentencing: Availability of Federal Grants Influenced Laws in Some States. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office.

- Rohrlich, Justin (November 10, 2014). "Why Are There Up to 120,000 Innocent People in US Prisons?". VICE news. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Hunt, Kasie (October 8, 2014). "Bill Clinton: Prison sentences to take center stage in 2016". MSNBC. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act |