Wanderer's Nightsong

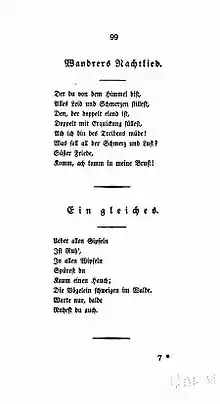

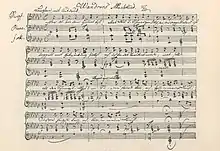

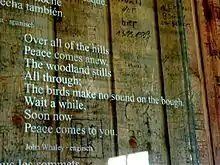

"Wanderer's Nightsong" (original German title: "Wandrers Nachtlied") is the title of two poems by the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Written in 1776 ("Der du von dem Himmel bist") and in 1780 ("Über allen Gipfeln"), they are among Goethe's most famous works. Both were first edited together in his 1815 Works Vol. I with the headings "Wandrers Nachtlied" and "Ein gleiches" ("Another one"). Both works were set to music as lieder by Franz Schubert as D 224 and D 768.

Wanderer's Nightsong I

The manuscript of "Wanderer's Nightsong" ("Der du von dem Himmel bist") was among Goethe's letters to his friend Charlotte von Stein and bears the signature "At the slope of Ettersberg, on 12 Feb. 76"; supposedly it was written under the tree later called the Goethe Oak.[1] One translation is by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

Der du von dem Himmel bist, |

Thou that from the heavens art, |

Franz Schubert set the poem to music in 1815, changing "stillest" and "füllest" to "stillst" and "füllst," and, more significantly, "Erquickung" (refreshment) to "Entzückung" (delight).

Wanderer's Nightsong II

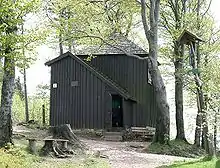

Wanderer's Nightsong II ("Über allen Gipfeln") is often considered the perhaps most perfect lyric in the German language.[3] Goethe probably wrote it on the evening of September 6, 1780, onto the wall of a wooden gamekeeper lodge on top of the Kickelhahn mountain near Ilmenau where he, according to a letter to Charlotte von Stein, spent the night.[4]

Über allen Gipfeln |

O'er all the hilltops |

_b_657.jpg.webp)

Goethe's friend Karl Ludwig von Knebel mentioned the writing in his diary, it is also documented in transcriptions by Johann Gottfried Herder and Luise von Göchhausen. It was first published—without authorization—by August Adolph von Hennings in 1800 and again by August von Kotzebue in 1803. An English version appeared in the Monthly Magazine in February 1801.[5] The second poem was also set to music by Franz Schubert, in 1823, Op. 96 No. 3, D. 768, it has been sung by sopranos, tenors and baritones, most notably by Dieter Fischer-Dieskau. As Goethe wrote to Carl Friedrich Zelter, he revisited the cabin more than 50 years later on August 27, 1831, about six months before his death. The poet recognised his wall-writing and reportedly broke down in tears. After 1831 the handwritten text vanished, and has not been preserved.

In popular culture

The mountain hut had already become famous as "Goethe's Cabin" by the late 1830s. Burnt down in 1870, it was rebuilt four years later. Parodies of "Nachtlied II" were written by Christian Morgenstern ("Fisches Nachtgesang"), Joachim Ringelnatz ("Abendgebet einer erkälteten Negerin", lines 17–20), Karl Kraus ("Wanderers Schlachtlied" from The Last Days of Mankind), and Bertolt Brecht ("Liturgie vom Hauch"). A computational linguistics processing of the poem was the topic of the 1968 radio drama Die Maschine by Georges Perec and Eugen Helmlé.[6] It is also cited in Daniel Kehlmann's 2005 novel Measuring the World,[7] in Milan Kundera's novel Immortality, and in Walter Moers' novel The City of Dreaming Books.

John Ottman's musical score for Bryan Singer's 2008 film Valkyrie contains a requiem-like piece for soprano and chorus in the closing credits with "Nachtlied II" as lyrics. In the film's context, the poem serves as a lament on the miscarried assassination on Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944, mourns the proximate death of most of the assassins, and with the last two lines forecasts the demise of those whom they failed to kill.[8]

References

- Gorra, Michael (2009). The Bells in Their Silence: Travels through Germany. Princeton UP. p. 16. ISBN 9781400826018.

- Adorno, Theodor W. (1989). "Lyric Poetry and Society". In Stephen Eric Bronner; Douglas Kellner (eds.). Critical Theory and Society: A Reader. Routledge. p. 170. ISBN 9780415900416.

- cf. Alan P. Cottrell: Goethe's view of evil and the search for a new image of man in our time (1982) p. 35

- Erich Trunz, in: Goethes Werke (Hamburger Ausgabe) vol. 1, 16th ed. 1996, p. 555

- The Monthly Magazine. Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper. July 29, 1801. p. 42. Retrieved July 29, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Perec, Georges; Helmlé, Eugen (1972). Die Maschine (in German). Stuttgart: Reclam.

- Kehlmann, Daniel (2005). Die Vermessung der Welt (in German). Reinbek: Rowohlt. pp. 127ff.

- "Composer John Ottman – Interview". tracksounds.com. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

External links

- Adaptation in English of "Wandrers Nachtlied II"

Media related to Wandrers Nachtlied at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wandrers Nachtlied at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)