Wandering albatross

The wandering albatross, snowy albatross, white-winged albatross or goonie[3] (Diomedea exulans) is a large seabird from the family Diomedeidae, which has a circumpolar range in the Southern Ocean. It was the last species of albatross to be described, and was long considered the same species as the Tristan albatross and the Antipodean albatross. A few authors still consider them all subspecies of the same species.[4] The SACC has a proposal on the table to split this species,[5] and BirdLife International has already split it. Together with the Amsterdam albatross, it forms the wandering albatross species complex. The wandering albatross is one of the two largest members of the genus Diomedea (the great albatrosses), being similar in size to the southern royal albatross. It is one of the largest, best known, and most studied species of bird in the world, with it possessing the greatest known wingspan of any living bird. This is also one of the most far ranging birds. Some individual wandering albatrosses are known to circumnavigate the Southern Ocean three times, covering more than 120,000 km (75,000 mi), in one year.[6]

| Wandering albatross | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Diomedeidae |

| Genus: | Diomedea |

| Species: | D. exulans |

| Binomial name | |

| Diomedea exulans | |

Taxonomy

The wandering albatross was first described as Diomedea exulans by Carl Linnaeus, in 1758, based on a specimen from the Cape of Good Hope.[3] Diomedea refers to Diomedes whose companions turned to birds, and exulans or exsul are Latin for "exile" or "wanderer" referring to its extensive flights.[7] The type locality has been restricted to South Georgia.[8]

Some experts considered there to be four subspecies of D. exulans, which they elevated to species status, and use the term wandering albatross to refer to a species complex that includes the proposed species D. antipodensis, D. dabbenena, D. exulans, and D. gibsoni.[9]

Description

The wandering albatross has the longest wingspan of any living bird, typically ranging from 2.51 to 3.5 m (8 ft 3 in to 11 ft 6 in), with a mean span of 3.1 m (10 ft 2 in) in the Bird Island, South Georgia colony and an average of exactly 3 m (9 ft 10 in) in 123 birds measured off the coast of Malabar, New South Wales.[3][10][11] On the Crozet Islands, adults averaged 3.05 m (10 ft 0 in) in wingspan.[12] The longest-winged examples verified have been about 3.7 m (12 ft 2 in).[11] Even larger examples have been claimed, with two giants reportedly measuring 4.22 m (13 ft 10 in) and 5.3 m (17 ft 5 in) but these reports remain unverified.[11] As a result of its wingspan, it is capable of remaining in the air without flapping its wings for several hours at a time (travelling 22 m for every metre of drop).[13][14][15] The length of the body is about 107 to 135 cm (3 ft 6 in to 4 ft 5 in)[10][16][17] with females being slightly smaller than males. Adults can weigh from 5.9 to 12.7 kg (13 to 28 lb), although most will weigh 6.35 to 11.91 kg (14.0 to 26.3 lb).[3][11][18][19] On Macquarie Island, three males averaged 8.4 kg (19 lb) and three females averaged 6.2 kg (14 lb).[20] In the Crozet Islands, males averaged 9.44 kg (20.8 lb) while females averaged 7.84 kg (17.3 lb).[12] However, 10 unsexed adults from the Crozets averaged 9.6 kg (21 lb).[21] On South Georgia, 52 males were found to average 9.11 kg (20.1 lb) while 53 females were found to average 7.27 kg (16.0 lb).[22] Immature birds have been recorded weighing as much as 16.1 kg (35 lb) during their first flights (at which time they may still have fat reserves that will be shed as they continue to fly).[11] On South Georgia, fledglings were found to average 10.9 kg (24 lb).[23] Albatrosses from outside the "snowy" wandering albatross group (D. exulans) are smaller but are now generally deemed to belong to different species.[22][24] The plumage varies with age, with the juveniles starting chocolate brown. As they age they become whiter.[3] The adults have white bodies with black and white wings. Males have whiter wings than females with just the tips and trailing edges of the wings black. The wandering albatross is the whitest of the wandering albatross species complex, the other species having a great deal more brown and black on the wings and body as breeding adults, very closely resembling immature wandering albatrosses. The large bill is pink, as are the feet.[17] They also have a salt gland that is situated above the nasal passage and helps desalinate their bodies, due to the high amount of ocean water that they imbibe. They excrete a high saline solution from their nose, which is a probable cause for the pink-yellow stain seen on some animal's necks.[25][26]

Distribution and habitat

The wandering albatross breeds on South Georgia Island, Crozet Islands, Kerguelen Islands, Prince Edward Islands, and Macquarie Island, is seen feeding year round off the Kaikoura Peninsula on the east coast of the south island of New Zealand[27] and it ranges in all the southern oceans from 28° to 60°.[1] Wandering albatrosses spend most of their life in flight, landing only to breed and feed. Distances travelled each year are hard to measure, but one banded bird was recorded travelling 6000 km in twelve days.

| Location | Population | Date | Trend |

| South Georgia Islands | 1,553 pairs | 2006 | Decreasing 4%/year |

| Prince Edward Island | 1,850 pairs | 2003 | Stable |

| Marion Island | 1,600 pairs | 2008 | |

| Crozet Islands | 2,000 pairs | 1997 | Declining |

| Kerguelen Islands | 1,100 pairs | 1997 | |

| Macquarie Island | 10 pairs | 2006 | |

| Total | 26,000 | 2007 |

Behaviour

Wanderers have a large range of displays from screams and whistles to grunts and bill clapping.[3] When courting they will spread their wings, wave their heads, and rap their bills together, while braying.[17] They can live for over 50 years.[28]

Breeding

Pairs of wandering albatrosses mate for life and breed every two years. Breeding takes place on subantarctic islands and commences in early November. The nest is a mound of mud and vegetation, and is placed on an exposed ridge near the sea. During the early stages of the chick's development, the parents take turns sitting on the nest while the other searches for food. Later, both adults hunt for food and visit the chick at irregular intervals.[29]

Feeding

Wandering albatrosses travel vast distances and tend to feed further out in open oceans than other albatrosses, whereas the related royal albatrosses in general tend to forage in somewhat shallower waters and closer to continental shelves.[30] They also tend to forage in colder waters further south than other albatrosses. They feed on cephalopods, small fish, and crustaceans[3] and on animal refuse that floats on the sea, eating to such excess at times that they are unable to fly and rest helplessly on the water. They are prone to following ships for refuse. They can also make shallow dives.

Reproduction

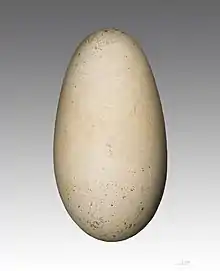

The wandering albatross breeds every other year.[16] At breeding time they occupy loose colonies on isolated island groups in the Southern Ocean. They lay one egg that is white, with a few spots, and is about 10 cm (3.9 in) long. They lay this egg between 10 December and 5 January. The nests are a large bowl built of grassy vegetation and soil peat,[3] that is 1 metre wide at the base and half a metre wide at the apex. Incubation takes about 11 weeks and both parents are involved.[16] They are a monogamous species, usually for life. Adolescents return to the colony within six years; however they will not start breeding until 11 to 15 years.[10] About 31.5% of fledglings survive.[3]

Relationship with humans

Sailors used to capture the birds for their long wing bones, from which they made tobacco-pipe stems. The early explorers of the great Southern Sea cheered themselves with the companionship of the albatross in their dreary solitudes; and the evil fate of him who shot with his cross-bow the "bird of good omen" is familiar to readers of Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The metaphor of "an albatross around his neck" also comes from the poem and indicates an unwanted burden causing anxiety or hindrance. In the days of sail the bird often accompanied ships for days, not merely following it, but wheeling in wide circles around it without ever being observed to land on the water. It continued its flight, apparently untired, in tempestuous as well as moderate weather.[31]

The Maori of New Zealand used albatrosses as a food source. They caught them by baiting hooks.[32] Because the wing bones of albatross were light but very strong Maori used these to create a number of different items including koauau (flutes),[33] needles, tattooing chisel blades,[34] and barbs for fish hooks.[35]

Conservation

The IUCN lists the wandering albatross as vulnerable status.[1] Adult mortality is 5% to 7.8% per year.[3] It has an occurrence range of 64,700,000 km2 (25,000,000 sq mi), although its breeding range is only 1,900 km2 (730 sq mi).

In 2007, there were an estimated 25,500 adult birds, broken down to 1,553 pairs on South Georgia Island, 1,850 pairs on Prince Edward Island, 1,600 on Marion Island, 2,000 on Crozet Islands, 1,100 on the Kerguelen Islands, and 12 on Macquarie Island for a total of 8,114 breeding pairs. The South Georgia population is shrinking at 1.8% per year. The levels of birds at Prince Edward and the Crozet Islands seem to be stabilising although most recently there may be some shrinking of the population.[17]

The biggest threat to their survival is longline fishing; however, pollution, mainly plastics and fishing hooks, are also taking a toll.

The CCAMLR has introduced measures to reduce bycatch of albatrosses around South Georgia by 99%, and other regional fishing commissions are taking similar measures to reduce fatalities. The Prince Edward Islands are a nature preserve, and the Macquarie Islands are a World Heritage site. Finally, large parts of the Crozet Islands and the Kerguelen Islands are a nature reserve.[17]

See also

- Sarus crane, the tallest flying bird alive today

- Bustards, which contain the heaviest living flying birds

- Pelagornis sandersi, the largest flying bird ever to live

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Diomedea exulans". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22698305A132640680. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- Brands, Sheila (Aug 14, 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification – Diomedea subg. Diomedea –". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved 12 Feb 2009.

- Robertson, C. J. R. (2003). "Albatrosses (Diomedeidae)". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 113–116, 118–119. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Clements, James (2007). The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World (6th ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- Remsen Jr., J. V.; et al. (30 Jan 2009). "Proposal (388) to South American Classification Committee: Split Diomedea exulans into four species". South American Classification Committee. American Ornithologists' Union. Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 17 Feb 2009.

- Weimerskirch, Henri; Delord, Karine; Guitteaud, Audrey; Phillips, Richard A.; Pinet, Patrick (2015). "Extreme variation in migration strategies between and within wandering albatross populations during their sabbatical year and their fitness consequences". Scientific Reports. 5: 8853. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E8853W. doi:10.1038/srep08853. PMC 4352845. PMID 25747757.

- Gotch, A. F. (1995) [1979]. "Albatrosses, Fulmars, Shearwaters, and Petrels". Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-8160-3377-5.

- Schodde, Richard; Tennyson, Alan J.D.; Groth, Jeff G.; Lai, Jonas; Scofield, Paul; Steinheimer, Frank D. (2017). "Settling the name Diomedea exulans Linnaeus, 1758 for the Wandering Albatross by neotypification". Zootaxa. 4236 (1): 135. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4236.1.7. PMID 28264342.

- Burg, T. M.; Croxall, J. P. (2004). "Global population structure and taxonomy of the wandering albatross species complex" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 13 (8): 2345–2355. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02232.x. PMID 15245406. S2CID 28479284.

- Dunn, Jon L.; Alderfer, Jonathon (2006). "Accidentals, Extinct Species". In Levitt, Barbara (ed.). National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America (fifth ed.). Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-7922-5314-3.

- Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- Shaffer, S. A.; Weimerskirch, H.; Costa, D. P. (2001). "Functional significance of sexual dimorphism in Wandering Albatrosses, Diomedea exulans". Functional Ecology. 15 (2): 203–210. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2001.00514.x. S2CID 49358426.

- Rattenborg, Niels, C. (2006). "Do Birds Sleep in Flight?". Naturwissenschaften. 93 (9): 413–425. Bibcode:2006NW.....93..413R. doi:10.1007/s00114-006-0120-3. PMID 16688436. S2CID 1736369.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Weimerskirch, Henri (Oct 2004). "Wherever the Wind May Blow." Natural History Magazine.

- Richardson, Michael (27 Sep 2002). "Endangered seabirds / New fishing techniques undercut an old talisman : Modern mariners pose rising threat to the albatross." Herald Tribune.

- Harrison, Colin; Greensmith, Alan (1993). "Non-Passerines". In Bunting, Edward (ed.). Birds of the World (First ed.). New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-56458-295-9.

- BirdLife International (2008). "Wandering Albatross – BirdLife Species Factsheet". Data Zone. Retrieved 17 Feb 2009.

- Wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans). arkive.org Archived 2011-02-15 at the Wayback Machine/

- "Encyclopedia of the Antarctic, v. 1 & v. 2. Beau Riffenburgh (Editor). Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-97024-2.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- Weimerskirch, H.; Shaffer, S. A.; Mabille, G.; Martin, J.; Boutard, O.; Rouanet, J. L. (2002). "Heart rate and energy expenditure of incubating wandering albatrosses: basal levels, natural variation, and the effects of human disturbance". Journal of Experimental Biology. 205 (4): 475–483. PMID 11893761.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses, 2nd Edition by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- Xavier, J.; Croxall, J.; Trathan, P.; Rodhouse, P. (2003). "Inter-annual variation in the cephalopod component of the diet of the wandering albatross, Diomedea exulans, breeding at Bird Island, South Georgia". Marine Biology. 142 (3): 611–622. doi:10.1007/s00227-002-0962-y. S2CID 83466498.

- Burg, T. M.; Croxall, J. P. (2004). "Global population structure and taxonomy of the wandering albatross species complex". Molecular Ecology. 13 (8): 2345–2355. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2004.02232.x. PMID 15245406. S2CID 28479284.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David, S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). The Birders Handbook (First ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-671-65989-9.

- Tickell, W.L.N. (2011). "Plumage contamination on Wandering Albatrosses – an aerodynamic model". Sea Swallow. 60: 67–69.

- Shirihai, Hadoram (2002) [2002]. "Great Albatrosses". Antarctic Wildlife The birds and mammals. Finland: Alula Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-951-98947-0-6.

- Is foraging efficiency a key parameter in aging?. Physorg (March 23, 2010)

- Monsanto (1987). "Long term observation of the wandering albatross: conclusions on migration, habitat, and breeding". Journal of Ornithology. 12 (28): 110–126.

- Imber, M.J. (1999). "Diet and Feeding Ecology of the Royal Albatross Diomedea epomophora – King of the Shelf Break and Inner Slope". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 99 (3): 200–211. doi:10.1071/MU99023.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Albatross". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 491.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Albatross". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 491. - "Matau Toroa (Albatross hook)". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- "Koauau (flute)". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- "Uhi Ta Moko (tattooing instruments)". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- "Matau (fish hook)". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

Further reading

- "Diomedea exulans". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 January 2006.

- Lindsey, T.R. 1986. The Seabirds of Australia. Angus and Robertson, and the National Photographic Index of Australian Wildlife Sydney.

- Marchant, S. and Higgins, P.J. (eds) 1993. Handbook of Australian New Zealand And Antarctic Birds Vol. 2: (Raptors To Lapwings). Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

- Parmelee, D.F. 1980. Bird Island in Antarctic Waters. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diomedea exulans. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Diomedea exulans. |

- Species factsheet – BirdLife International

- Fact file – ARKive

- Video, photos and sounds – Internet Bird Collection

- Holotype photos – Collections Online, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Do albatrosses have personalities? – Video, Te Papa Channel, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Slide show – Expeditionsail