Wasteland (video game)

Wasteland is a science fiction open world role-playing video game developed by Interplay and published by Electronic Arts at the beginning of 1988.[5] The game is set in a futuristic, post-apocalyptic America destroyed by nuclear holocaust generations before. Developers originally made the game for the Apple II and it was ported to the Commodore 64 and MS-DOS. It was re-released for Microsoft Windows, OS X, and Linux in 2013 via Steam and GOG.com, and in 2014 via Desura.

| Wasteland | |

|---|---|

Cover art by Barry E. Jackson[1] | |

| Developer(s) | Interplay Productions Krome Studios (remaster) |

| Publisher(s) | Electronic Arts inXile Entertainment (remaster) Xbox Game Studios (remaster) |

| Director(s) | Brian Fargo |

| Producer(s) | David Albert |

| Designer(s) | Ken St. Andre Michael A. Stackpole Liz Danforth |

| Programmer(s) | Alan Pavlish |

| Artist(s) | Todd J. Camasta Bruce Schlickbernd Charles H. H. Weidman III |

| Writer(s) | Ken St. Andre Michael A. Stackpole |

| Composer(s) | Edwin Montgomery (remaster)[2] |

| Series | Wasteland |

| Platform(s) | Apple II (original) Commodore 64 MS-DOS Microsoft Windows OS X Linux Xbox One (remaster) |

| Release | January 2, 1988[3][4] February 25, 2020 (remaster) |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Critically acclaimed and commercially successful, Wasteland was intended to be followed by two separate sequels, but Electronic Arts' Fountain of Dreams was turned into an unrelated game and Interplay's Meantime was cancelled. The game's general setting and concept became the basis for Interplay's 1997 role-playing video game Fallout, which would extend into the Fallout series. Game developer inXile Entertainment released a sequel, Wasteland 2, in 2014. Wasteland 3 was released on August 28, 2020. Wasteland Remastered was released on February 25, 2020.

Gameplay

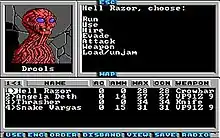

Wasteland's game mechanics are based on those used in the tabletop role-playing games, such as Tunnels and Trolls and Mercenaries, Spies and Private Eyes created by Wasteland designers Ken St. Andre and Michael Stackpole.[6] Characters in Wasteland have various statistics (strength, intelligence, luck, speed, agility, dexterity, and charisma) that allow the characters to use different skills and weapons. Experience is gained through battle and skill usage. The game generally lets players advance using a variety of tactics: to get through a locked gate, the characters could use their picklock skill, their climb skill, or their strength attribute; or they could force the gate with a crowbar or a LAW rocket.

The player's party begins with four characters. Through the course of the game the party can hold as many as seven characters by recruiting certain citizens and wasteland creatures. Unlike those of other computer RPGs of the time, these non-player characters (NPCs) might at times refuse to follow the player's commands, such as when the player orders the character to give up an item or perform an action.[7] The game is noted for its high and unforgiving difficulty level.[8] The prose appearing in the game's combat screens, such as phrases saying an enemy is "reduced to a thin red paste" and "explodes like a blood sausage", prompted an unofficial PG-13 sticker on the game packaging in the U.S.[7]

Wasteland was one of the first games featuring a persistent world, where changes to the game world were stored and kept.[8] Returning to an area later in the game, the player would find it in the state the player left it in, rather than being reset, as was common for games of the time. Since hard drives were still rare in home computers in 1988, this meant the original game disk had to be copied first, as the manual instructed one to do.[9]

Another feature of the game was the inclusion of a printed collection of paragraphs that the player would read at the appropriate times.[10] These paragraphs described encounters and conversations, contained clues, and added to the overall texture of the game. Because programming space was at a premium, it saved on resources to have most of the game's story printed out in a separate manual rather than stored within the game's code itself. The paragraph books also served as a rudimentary form of copy protection; someone playing a copied version of the game would miss out on much of the story and clues necessary to progress. The paragraphs included an unrelated story line[8] about a mission to Mars intended to mislead those who read the paragraphs when not instructed to, and a false set of passwords that would trip up cheaters.

Plot

In 2087 (one hundred years after the game's development), generations after the devastation of a global nuclear war in 1998, a distant remnant force of the U.S. Army called the Desert Rangers is based in the Southwestern United States, acting as peacekeepers to protect fellow survivors and their descendants. A team of Desert Rangers is assigned to investigate a series of disturbances in nearby areas. Throughout the game, the rangers explore the remaining enclaves of human civilization, including a post-apocalyptic Las Vegas.[11]

As the group's investigation deepens, the Rangers discover evidence of a larger menace threatening to exterminate what is left of humankind. A pre-war artificial intelligence operating from a surviving military facility, Base Cochise, is constructing armies of killer machines and cybernetically modified humans to attack human settlements with the help of Irwin Finster, the deranged former commander of the base. Finster has gone so far as to transform himself into a cyborg under the AI's control. The AI's ultimate goal is to complete "Project Darwin" (which Finster was in charge of) and replace the world's "flawed" population with genetically pure specimens. With help from a pre-war android named Max, the player recovers the necessary technology and weapons in order to confront the AI at Base Cochise and destroy it by making the base's nuclear reactor melt down.

Development and release

Brian Fargo in an interview with Hartley and Patricia Lesse for MicroTimes in 1987 said that Interplay started work on the game about a year ago. Fargo further stated that game was created on Apple II as it was equally important to him like the Commodore 64. He described the game as a hybrid of Ultima games and The Bard's Tale, while being post-apocalyptic and in a similar vein as the Mad Max films. He described the combat as being similar to The Bard's Tale though also containing strategy, players being able to disband parties or split up party members for exploration, selecting the point-of-view of different members.[12]

It was stated in January 1987 that Michael Stackpole, who authored Mercenaries, Spies and Private Eyes and Batman's sourcebook for DC Heroes, would be involved as the game's writer. Close to release, Interplay insisted that it be labelled PG-13.[13][14]

Fargo in an interview with Patrick Hickey Jr. has stated that the genesis of Wasteland came after The Bard's Tale was a hit, as they wanted to make another role-playing video game for Electronic Arts asides from a sequel to The Bard's Tale. He added that due to his love for Mad Max 2 and post-apocalyptic fiction, he chose a post-apocalyptic setting for this new RPG. While searching for a gameplay system for their new game, they came across the system of Mercenaries, Spies and Private Eyes.[15]

Ken St. Andre described to Hickey that they wanted to make a game-changing computer role-playing game that will be better than any other at the time, hating the limitations other CRPGs put on gamers. According to him, the process of creating the story of the game took over a year, though it was mostly due to them feeding various possible scenarios into how the game should react at a given time. Wasteland's different story was mostly because of St. Andre and Stackpole who wanted something new.[16]

The original plot was supposed to be similar to Red Dawn, with Russians occupying the United States and fighting against Americans engaged in liberating their nation. St. Andre eventually decided to change this and pitched a new story involving killer robots wanting to wipe out as well as replace humanity, which he called a sort of cross between The Terminator and Daffy Duck, and Brian accepted this new storyline. The location of the game was chosen due to St. Andre living in the region and his familiarity with the area, while making sure the locations of real-world places were accurate in the game.[16][17]

Alan Pavlish had been chosen to be the lead developer of the video game, writing the game in Apple II machine language and programming the game to react to player choices. Per St. Andre, Fargo's pitch to him was of a post-nuclear holocaust game which took advantage of Pavlish's coding, which allowed for weapons capable of inflicting area effect damage to be used and the map be modified "on the fly".[18]

The game was copyrighted in 1986.[19] Said to be in development for five years,[20][15] Wasteland was originally released for the Apple II, Commodore 64, and IBM compatibles. The IBM version added an additional skill called "Combat Shooting" which could be bought only when a character was first created.

Wasteland was re-released as part of Interplay's 10 Year Anthology: Classic Collection in 1995,[21] and also included in the 1998 Ultimate RPG Archives through Interplay's DragonPlay label.[22] These later bundled releases were missing the original setup program, which allowed the game's maps to be reset, while retaining the player's original team of Rangers. Jeremy Reaban wrote an unofficial (and unsupported) program that emulated this functionality.[23]

Reception

Computer Gaming World cited Wasteland's "ease of play, richness of plot, problem solving requirements, skill and task system, and graphic display" as elements of its excellence.[24] The magazine's Scorpia favorably reviewed the game in 1991 and 1993, calling it "really the only decently-designed post-nuke game on the market".[25][26] In 1992 the magazine stated that the game's "classic mix of combat and problem-solving" was the favorite of its readers in 1988, and that "the way in which Wasteland's NPCs related to the player characters, the questions of dealing with moral dillemas, and the treatment of skills set this game apart."[27] In 1994 the magazine mentioned Wasteland as an example of how "older, less sophisticated engines can still play host to a great game".[28] Orson Scott Card gave Wasteland a mixed review in Compute!, commending the science fiction elements and setting, but stating that "mutant bunnies can get boring, too ... This is still a kill-the-monster-and-get-the-treasure game, without the overarching story that makes each Ultima installment meaningful."[29] Another writer for Compute! praised the game, however, citing its non-linear design and multiple puzzle solutions, the vague nature of the goal, and customizable player stats.[30]

Julia Martin's review for Challenge favorably recommended the game for those into RPGs and adventure games, comparing it to Twilight: 2000, praising its combat system, choices and for differing from the usual sword-and-fantasy genre. She called the game well done and stated it offered hours of fun. She also criticized having to insert the primary "A" disk in order to play the game after copying it from four disks, the game's save system and characters starting out with useless items.[31]

The game was a hit and at its time of release, it sold around 250,000 units.[32] Computer Gaming World awarded Wasteland the Adventure Game of the Year award in 1988.[33] The game received the fourth-highest number of votes in a 1990 survey of the magazine's readers' "All-Time Favorites".[34] In 1993 Computer Gaming World added Wasteland to its Hall of Fame,[35] and in 1996, rated it as the ninth best PC video game of all time for introducing the concept of the player's party "acting like the 'real' people."[36] In 2000, Wasteland was ranked as the 24th top PC game of all time by the staff of IGN, who called it "one of the best RPGs to ever grace the PC" and "a truly innovative RPG for its time."[11]

According to a retrospective review by Richard Cobbett of Eurogamer in 2012, "even now, it offers a unique RPG world and experience ... a whole fallen civilisation full of puzzles and characters and things to twiddle with, all magically crammed into less than a megabyte of space."[10] In another retrospective article that same year, IGN's Kristan Reed wrote that "time has not been kind to Wasteland, but its core concepts stand firm."[8]

Legacy

Sequels and spiritual successor

Wasteland was followed in 1990 by a less-successful intended sequel, Fountain of Dreams, set in post-war Florida. At the last moment, however, Electronic Arts decided to not advertise it as a sequel to Wasteland. None of the creative cast from Wasteland worked on Fountain of Dreams. Interplay themselves worked on Meantime, which was based on the Wasteland game engine and its universe but was not a continuation of the story. Coding of Meantime was nearly finished and a beta version was produced, but the game was canceled when the 8-bit computer game market went into decline.

Interplay has described its 1997 game Fallout as the spiritual successor to Wasteland. According to IGN, "Interplay's inability to prise the Wasteland brand name from EA's gnarled fingers actually led to it creating Fallout in the first place."[8] There are Wasteland homage elements in Fallout and Fallout 2 as well.[7][8] All games in the Fallout series are set in the world described by its characters as "Wasteland" (for example, the "Midwest Wasteland" in Fallout Tactics: Brotherhood of Steel or the "Capital Wasteland" in Fallout 3). A recruitable character named Tycho in Fallout is described as a Desert Ranger who is a descendant of an original Desert Ranger, who had taught the previous survival skills. A major part of the Fallout universe is the military organization Brotherhood of Steel, whose origins are similar to the Desert Rangers and the Guardians of the Old Order of Wasteland; a group called the Desert Rangers actually appears in Fallout: New Vegas.

Wasteland 2 was developed by Brian Fargo's inXile Entertainment and published on September 19, 2014. The game's production team included the original Wasteland designers Alan Pavlish, Michael A. Stackpole, Ken St. Andre and Liz Danforth, and was crowdfunded through a highly successful Kickstarter campaign. InXile Entertainment announced on September 28, 2016, that it was crowdfunding on Fig to develop another sequel, Wasteland 3. The game is expected to be released on Windows, Mac, Linux, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One in 2020.[37][38]

Re-release

In a Kickstarter update for Wasteland 2 on August 9, 2013, project lead Chris Keenan announced that they had reached an agreement with Electronic Arts to release the game for modern operating systems. He added that it will be given for free to backers of Wasteland 2 on Kickstarter, in addition to being made available for purchase on GOG and Steam.[39] The re-released was designed to run on higher resolutions and added in a song by Mark Morgan, higher resolution portraits, the ability to use the original game's manual in-game and paragraph book's text as well as expanding the save-game functionality.[40]

On November 7, he announced that the re-release titled Wasteland 1 - The Original Classic had gone gold and had been submitted to GOG and Steam for approval. In response to the player feedback, inXile included the ability to turn off smoothing, including the manual in tooltips, swapping and tweaking portraits while making it work on Mac OS X and Linux. Those who backed Planescape: Torment and received Wasteland 2, also received the re-release for free.[41]

The Original Classic edition was released on November 8, 2013 and was downloaded over 33,000 times before its general availability.[42] On November 12, the game was released on GOG.[43] The next day, the game was also released on Steam for the Windows, Mac and Linux.[44] The game was released on March 11, 2014 for Desura.[45]

Remaster

inXile Entertainment announced a remastered version in honor of the original's 30th anniversary, adding it was being produced by Krome Studios.[46] During E3 2019, Brian Fargo announced it was coming to both Windows and Xbox One.[47] He also released screenshots of the game.[48] On 23 January 2020, the release date was revealed as 25 February.[49] It was released on GOG, Steam and Microsoft Store. The graphics and sound were completely overhauled and the game uses 3D models. In addition, it also features voiced lines and new portraits for characters.[50] The "remastered" edition features cross-save support and Xbox Play Anywhere support.[51]

References

- "Limited and signed art print from the grandfather of post apocalyptic RPGs... Wasteland". wasteland.inxile-entertainment.com. inXile Entertainment. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- "Interview with Wasteland Remastered's Composer, Edwin Montgomery". inXile Entertainment. March 10, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- "Wasteland 1: The Original Classic". www.gog.com. GOG. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- Barton, Matt (February 23, 2007). "Part 2: The Golden Age (1985-1993)". The History of Computer Role-Playing Games. Gamasutra. Archived from the original on March 27, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Nutt, Christian. "Wasteland : Developing an open-world RPG in 1988". Archived from the original on February 7, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Tringham, Neal Roger (September 4, 2014). Science Fiction Video Games. CRC Press. p. 203. ISBN 9781482203899. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017.

- Plunkett, Luke (February 17, 2012). "Why People Give a Shit About a 1988 PC Role-Playing Game". Kotaku.com. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Why Wasteland 2 is Worth Getting Excited About Archived 2012-02-24 at the Wayback Machine, IGN, March 16, 2012

- "Commodore 64/128 Wasteland Reference Card" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2014.

- "Retrospective: Wasteland". Eurogamer. March 25, 2012. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012.

- "The Top 25 PC Games of All Time". IGN. July 17, 2000. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- Lesse, Hartley; Lesse, Patricia (March 1987). "The Programmer's Tale". MicroTimes. Vol. 4 no. 2. BAM Publications Inc. p. 200.

- "Taking a Peek" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 34. January–February 1987. p. 10.

- "Sneak Preview: Wasteland" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. No. 45. March 1988. p. 26.

- Hickey Jr., Patrick (April 9, 2018). The Minds Behind the Games: Interviews with Cult and Classic Video Game Developers. McFarland. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9781476671109.

- Hickey Jr., Patrick (April 9, 2018). The Minds Behind the Games: Interviews with Cult and Classic Video Game Developers. McFarland. pp. 202–203. ISBN 9781476671109.

- Barton, Matt (April 9, 2018). Vintage Games 2.0: An Insider Look at the Most Influential Games of All Time. CRC Press. pp. 193–196. ISBN 9781000000924.

- Hickey Jr., Patrick (April 9, 2018). The Minds Behind the Games: Interviews with Cult and Classic Video Game Developers. McFarland. pp. 203–204. ISBN 9781476671109.

- "Computer Gaming World Hall of Fame". Computer Gaming World. No. 115. February 1994. p. 221.

- Barton, Matt (January 23, 2011). "Matt Chat 90: Wasteland and Fallout with Brian Fargo". YouTube. Archived from the original on January 25, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- "Interplay's 10 Year Anthology for DOS (1993)". MobyGames. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- "The Ultimate RPG Archives - PC - GameSpy". Uk.pc.gamespy.com. January 31, 1998. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- "The Unofficial Wasteland Reset Program". Wasteland.rockdud.net. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- Kritzen, William (May 1988). "Wasted in the Wasteland". Computer Gaming World. pp. 28–29. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016.

- Scorpia (October 1991). "C*R*P*G*S / Computer Role-Playing Game Survey". Computer Gaming World. p. 16. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- Scorpia (October 1993). "Scorpia's Magic Scroll Of Games". Computer Gaming World. pp. 34–50. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- Sipe, Russell (November 1992). "3900 Games Later..." Computer Gaming World. p. 8. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- Yee, Bernie (April 1994). "Too Much, Two Late". Computer Gaming World. pp. 62, 64. Archived from the original on November 11, 2017. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- Card, Orson Scott (June 1989). "Light-years and Lasers / Science Fiction Inside Your Computer". Compute!. p. 29. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- Trunzo, James V. (November 1988). "Wasteland". Compute!. p. 78. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- Martin, Julia (1989). "Reviews". Challenge. No. 38. pp. 76–77.

- Hickey Jr., Patrick (April 9, 2018). The Minds Behind the Games: Interviews with Cult and Classic Video Game Developers. McFarland. p. 201. ISBN 9781476671109.

- "Computer Gaming World's 1988 Game of the Year Awards". Computer Gaming World. October 1988. p. 54.

- "CGW Readers Select All-Time Favorites". Computer Gaming World. January 1990. p. 64. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- "Induction Ceremony!". Computer Gaming World. February 1993. p. 157. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. pp. 64–80. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2016.

- Dornbush, Jonathon (September 28, 2016). "Wasteland 3 announced, will include co-op". IGN. Ziff Davis, LLC. Archived from the original on September 28, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

Wasteland 2 developer InXile Games has announced a sequel to the 2014 RPG, Wasteland 3, and the developer is using Fig to raise funds for the game. The campaign will launch on Fig on October 5 with a total goal of $2.75 million and a planned release on Windows, Mac, Linux, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One.

- Brown, Fraser (June 12, 2019). "Wasteland 3 is coming next spring". PC Gamer. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- Sykes, Tom (August 10, 2013). "Wasteland 1 to get Steam and GOG releases". PC Gamer. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Carmichael, Stephanie (November 7, 2013). "Wasteland 1 – The Original Classic goes gold for GOG and Steam". Gamezone. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Miller, Ewan (November 7, 2013). "Wasteland 1 has been submitted to Good Old Games and Steam". VG247. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Cowan, Danny (November 14, 2013). "Classic post-apocalyptic RPG Wasteland out now on Steam, GOG". Engadget. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Shearer, Stew (November 12, 2013). "Wasteland Comes to GOG". The Escapist. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "Now Available on Steam - Wasteland 1 - The Original Classic". Steam. November 13, 2013. Archived from the original on November 16, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- "Wasteland 1 - The Original Classic Available on Desura". inXile Entertainment. Tumblr. March 11, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Costa, Richard (June 11, 2018). "InXile Entertainment Announces Wasteland 30th Anniversary Bundle". Techraptor. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Madan, Asher (June 12, 2019). "Cult classic 'Wasteland' confirmed for Xbox One, remaster also coming to PC". Windows Central. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Reuben, Nic (June 14, 2019). "Wasteland remaster looks a whole lot like a remake, and I'm not complaining". Rock Paper and Shotgun. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Prescott, Shaun (January 23, 2020). "Wasteland Remastered will release next month". Rock Paper and Shotgun. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Amy, Matt (February 25, 2020). "Wasteland Remastered Survival Guide". Xbox News. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Amy, Matt (February 25, 2020). "Wasteland Remastered is Available Now with Xbox Game Pass on Xbox One and Windows 10 PC". Xbox News. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

External links

- Wasteland at MobyGames

- Wasteland can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive