Nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor, formerly known as an atomic pile, is a device used to initiate and control a self-sustained nuclear chain reaction. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nuclear fission is passed to a working fluid (water or gas), which in turn runs through steam turbines. These either drive a ship's propellers or turn electrical generators' shafts. Nuclear generated steam in principle can be used for industrial process heat or for district heating. Some reactors are used to produce isotopes for medical and industrial use, or for production of weapons-grade plutonium. As of early 2019, the IAEA reports there are 454 nuclear power reactors and 226 nuclear research reactors in operation around the world.[1][2][3]

Operation

Just as conventional thermal power stations generate electricity by harnessing the thermal energy released from burning fossil fuels, nuclear reactors convert the energy released by controlled nuclear fission into thermal energy for further conversion to mechanical or electrical forms.

Fission

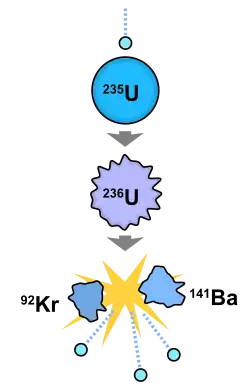

When a large fissile atomic nucleus such as uranium-235 or plutonium-239 absorbs a neutron, it may undergo nuclear fission. The heavy nucleus splits into two or more lighter nuclei, (the fission products), releasing kinetic energy, gamma radiation, and free neutrons. A portion of these neutrons may be absorbed by other fissile atoms and trigger further fission events, which release more neutrons, and so on. This is known as a nuclear chain reaction.

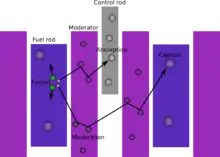

To control such a nuclear chain reaction, Control rods containing neutron poisons and neutron moderators can change the portion of neutrons that will go on to cause more fission.[4] Nuclear reactors generally have automatic and manual systems to shut the fission reaction down if monitoring detects unsafe conditions.[5]

Heat generation

The reactor core generates heat in a number of ways:

- The kinetic energy of fission products is converted to thermal energy when these nuclei collide with nearby atoms.

- The reactor absorbs some of the gamma rays produced during fission and converts their energy into heat.

- Heat is produced by the radioactive decay of fission products and materials that have been activated by neutron absorption. This decay heat source will remain for some time even after the reactor is shut down.

A kilogram of uranium-235 (U-235) converted via nuclear processes releases approximately three million times more energy than a kilogram of coal burned conventionally (7.2 × 1013 joules per kilogram of uranium-235 versus 2.4 × 107 joules per kilogram of coal).[6][7]

Cooling

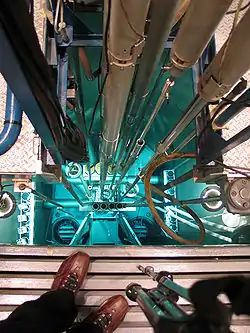

A nuclear reactor coolant — usually water but sometimes a gas or a liquid metal (like liquid sodium or lead) or molten salt — is circulated past the reactor core to absorb the heat that it generates. The heat is carried away from the reactor and is then used to generate steam. Most reactor systems employ a cooling system that is physically separated from the water that will be boiled to produce pressurized steam for the turbines, like the pressurized water reactor. However, in some reactors the water for the steam turbines is boiled directly by the reactor core; for example the boiling water reactor.[8]

Reactivity control

The rate of fission reactions within a reactor core can be adjusted by controlling the quantity of neutrons that are able to induce further fission events. Nuclear reactors typically employ several methods of neutron control to adjust the reactor's power output. Some of these methods arise naturally from the physics of radioactive decay and are simply accounted for during the reactor's operation, while others are mechanisms engineered into the reactor design for a distinct purpose.

The fastest method for adjusting levels of fission-inducing neutrons in a reactor is via movement of the control rods. Control rods are made of neutron poisons and therefore absorb neutrons. When a control rod is inserted deeper into the reactor, it absorbs more neutrons than the material it displaces—often the moderator. This action results in fewer neutrons available to cause fission and reduces the reactor's power output. Conversely, extracting the control rod will result in an increase in the rate of fission events and an increase in power.

The physics of radioactive decay also affects neutron populations in a reactor. One such process is delayed neutron emission by a number of neutron-rich fission isotopes. These delayed neutrons account for about 0.65% of the total neutrons produced in fission, with the remainder (termed "prompt neutrons") released immediately upon fission. The fission products which produce delayed neutrons have half-lives for their decay by neutron emission that range from milliseconds to as long as several minutes, and so considerable time is required to determine exactly when a reactor reaches the critical point. Keeping the reactor in the zone of chain reactivity where delayed neutrons are necessary to achieve a critical mass state allows mechanical devices or human operators to control a chain reaction in "real time"; otherwise the time between achievement of criticality and nuclear meltdown as a result of an exponential power surge from the normal nuclear chain reaction, would be too short to allow for intervention. This last stage, where delayed neutrons are no longer required to maintain criticality, is known as the prompt critical point. There is a scale for describing criticality in numerical form, in which bare criticality is known as zero dollars and the prompt critical point is one dollar, and other points in the process interpolated in cents.

In some reactors, the coolant also acts as a neutron moderator. A moderator increases the power of the reactor by causing the fast neutrons that are released from fission to lose energy and become thermal neutrons. Thermal neutrons are more likely than fast neutrons to cause fission. If the coolant is a moderator, then temperature changes can affect the density of the coolant/moderator and therefore change power output. A higher temperature coolant would be less dense, and therefore a less effective moderator.

In other reactors the coolant acts as a poison by absorbing neutrons in the same way that the control rods do. In these reactors power output can be increased by heating the coolant, which makes it a less dense poison. Nuclear reactors generally have automatic and manual systems to scram the reactor in an emergency shut down. These systems insert large amounts of poison (often boron in the form of boric acid) into the reactor to shut the fission reaction down if unsafe conditions are detected or anticipated.[9]

Most types of reactors are sensitive to a process variously known as xenon poisoning, or the iodine pit. The common fission product Xenon-135 produced in the fission process acts as a neutron poison that absorbs neutrons and therefore tends to shut the reactor down. Xenon-135 accumulation can be controlled by keeping power levels high enough to destroy it by neutron absorption as fast as it is produced. Fission also produces iodine-135, which in turn decays (with a half-life of 6.57 hours) to new xenon-135. When the reactor is shut down, iodine-135 continues to decay to xenon-135, making restarting the reactor more difficult for a day or two, as the xenon-135 decays into cesium-135, which is not nearly as poisonous as xenon-135, with a half-life of 9.2 hours. This temporary state is the "iodine pit." If the reactor has sufficient extra reactivity capacity, it can be restarted. As the extra xenon-135 is transmuted to xenon-136, which is much less a neutron poison, within a few hours the reactor experiences a "xenon burnoff (power) transient". Control rods must be further inserted to replace the neutron absorption of the lost xenon-135. Failure to properly follow such a procedure was a key step in the Chernobyl disaster.[10]

Reactors used in nuclear marine propulsion (especially nuclear submarines) often cannot be run at continuous power around the clock in the same way that land-based power reactors are normally run, and in addition often need to have a very long core life without refueling. For this reason many designs use highly enriched uranium but incorporate burnable neutron poison in the fuel rods.[11] This allows the reactor to be constructed with an excess of fissionable material, which is nevertheless made relatively safe early in the reactor's fuel burn cycle by the presence of the neutron-absorbing material which is later replaced by normally produced long-lived neutron poisons (far longer-lived than xenon-135) which gradually accumulate over the fuel load's operating life.

Electrical power generation

The energy released in the fission process generates heat, some of which can be converted into usable energy. A common method of harnessing this thermal energy is to use it to boil water to produce pressurized steam which will then drive a steam turbine that turns an alternator and generates electricity.[9]

Early reactors

The neutron was discovered in 1932 by British physicist James Chadwick. The concept of a nuclear chain reaction brought about by nuclear reactions mediated by neutrons was first realized shortly thereafter, by Hungarian scientist Leó Szilárd, in 1933. He filed a patent for his idea of a simple reactor the following year while working at the Admiralty in London.[12] However, Szilárd's idea did not incorporate the idea of nuclear fission as a neutron source, since that process was not yet discovered. Szilárd's ideas for nuclear reactors using neutron-mediated nuclear chain reactions in light elements proved unworkable.

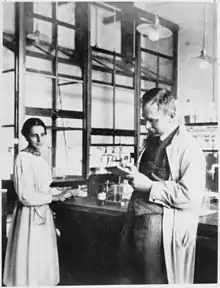

Inspiration for a new type of reactor using uranium came from the discovery by Lise Meitner, Fritz Strassmann and Otto Hahn in 1938 that bombardment of uranium with neutrons (provided by an alpha-on-beryllium fusion reaction, a "neutron howitzer") produced a barium residue, which they reasoned was created by the fissioning of the uranium nuclei. Subsequent studies in early 1939 (one of them by Szilárd and Fermi) revealed that several neutrons were also released during the fissioning, making available the opportunity for the nuclear chain reaction that Szilárd had envisioned six years previously.

On 2 August 1939 Albert Einstein signed a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt (written by Szilárd) suggesting that the discovery of uranium's fission could lead to the development of "extremely powerful bombs of a new type", giving impetus to the study of reactors and fission. Szilárd and Einstein knew each other well and had worked together years previously, but Einstein had never thought about this possibility for nuclear energy until Szilard reported it to him, at the beginning of his quest to produce the Einstein-Szilárd letter to alert the U.S. government.

Shortly after, Hitler's Germany invaded Poland in 1939, starting World War II in Europe. The U.S. was not yet officially at war, but in October, when the Einstein-Szilárd letter was delivered to him, Roosevelt commented that the purpose of doing the research was to make sure "the Nazis don't blow us up." The U.S. nuclear project followed, although with some delay as there remained skepticism (some of it from Fermi) and also little action from the small number of officials in the government who were initially charged with moving the project forward.

The following year the U.S. Government received the Frisch–Peierls memorandum from the UK, which stated that the amount of uranium needed for a chain reaction was far lower than had previously been thought. The memorandum was a product of the MAUD Committee, which was working on the UK atomic bomb project, known as Tube Alloys, later to be subsumed within the Manhattan Project.

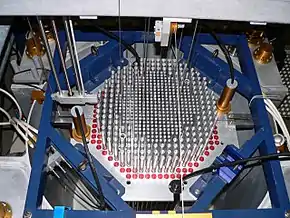

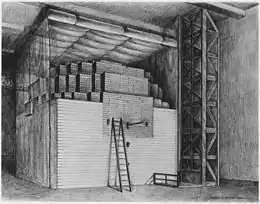

Eventually, the first artificial nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, was constructed at the University of Chicago, by a team led by Italian physicist Enrico Fermi, in late 1942. By this time, the program had been pressured for a year by U.S. entry into the war. The Chicago Pile achieved criticality on 2 December 1942[13] at 3:25 PM. The reactor support structure was made of wood, which supported a pile (hence the name) of graphite blocks, embedded in which was natural uranium oxide 'pseudospheres' or 'briquettes'.

Soon after the Chicago Pile, the U.S. military developed a number of nuclear reactors for the Manhattan Project starting in 1943. The primary purpose for the largest reactors (located at the Hanford Site in Washington), was the mass production of plutonium for nuclear weapons. Fermi and Szilard applied for a patent on reactors on 19 December 1944. Its issuance was delayed for 10 years because of wartime secrecy.[14]

"World's first nuclear power plant" is the claim made by signs at the site of the EBR-I, which is now a museum near Arco, Idaho. Originally called "Chicago Pile-4", it was carried out under the direction of Walter Zinn for Argonne National Laboratory.[15] This experimental LMFBR operated by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission produced 0.8 kW in a test on 20 December 1951[16] and 100 kW (electrical) the following day,[17] having a design output of 200 kW (electrical).

Besides the military uses of nuclear reactors, there were political reasons to pursue civilian use of atomic energy. U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower made his famous Atoms for Peace speech to the UN General Assembly on 8 December 1953. This diplomacy led to the dissemination of reactor technology to U.S. institutions and worldwide.[18]

The first nuclear power plant built for civil purposes was the AM-1 Obninsk Nuclear Power Plant, launched on 27 June 1954 in the Soviet Union. It produced around 5 MW (electrical).

After World War II, the U.S. military sought other uses for nuclear reactor technology. Research by the Army and the Air Force never came to fruition; however, the U.S. Navy succeeded when they steamed the USS Nautilus (SSN-571) on nuclear power 17 January 1955.

The first commercial nuclear power station, Calder Hall in Sellafield, England was opened in 1956 with an initial capacity of 50 MW (later 200 MW).[19][20]

The first portable nuclear reactor "Alco PM-2A" was used to generate electrical power (2 MW) for Camp Century from 1960 to 1963.[21]

Reactor types

- PWR: 277 (63.2%)

- BWR: 80 (18.3%)

- GCR: 15 (3.4%)

- PHWR: 49 (11.2%)

- LWGR: 15 (3.4%)

- FBR: 2 (0.5%)

- PWR: 257.2 (68.3%)

- BWR: 75.5 (20.1%)

- GCR: 8.2 (2.2%)

- PHWR: 24.6 (6.5%)

- LWGR: 10.2 (2.7%)

- FBR: 0.6 (0.2%)

Classifications

By type of nuclear reaction

All commercial power reactors are based on nuclear fission. They generally use uranium and its product plutonium as nuclear fuel, though a thorium fuel cycle is also possible. Fission reactors can be divided roughly into two classes, depending on the energy of the neutrons that sustain the fission chain reaction:

- Thermal neutron reactors (the most common type of nuclear reactor) use slowed or thermal neutrons to keep up the fission of their fuel. Almost all current reactors are of this type. These contain neutron moderator materials that slow neutrons until their neutron temperature is thermalized, that is, until their kinetic energy approaches the average kinetic energy of the surrounding particles. Thermal neutrons have a far higher cross section (probability) of fissioning the fissile nuclei uranium-235, plutonium-239, and plutonium-241, and a relatively lower probability of neutron capture by uranium-238 (U-238) compared to the faster neutrons that originally result from fission, allowing use of low-enriched uranium or even natural uranium fuel. The moderator is often also the coolant, usually water under high pressure to increase the boiling point. These are surrounded by a reactor vessel, instrumentation to monitor and control the reactor, radiation shielding, and a containment building.

- Fast neutron reactors use fast neutrons to cause fission in their fuel. They do not have a neutron moderator, and use less-moderating coolants. Maintaining a chain reaction requires the fuel to be more highly enriched in fissile material (about 20% or more) due to the relatively lower probability of fission versus capture by U-238. Fast reactors have the potential to produce less transuranic waste because all actinides are fissionable with fast neutrons,[23] but they are more difficult to build and more expensive to operate. Overall, fast reactors are less common than thermal reactors in most applications. Some early power stations were fast reactors, as are some Russian naval propulsion units. Construction of prototypes is continuing (see fast breeder or generation IV reactors).

In principle, fusion power could be produced by nuclear fusion of elements such as the deuterium isotope of hydrogen. While an ongoing rich research topic since at least the 1940s, no self-sustaining fusion reactor for power generation has ever been built.

By moderator material

Used by thermal reactors:

- Graphite-moderated reactors

- Water moderated reactors

- Heavy-water reactors (Used in Canada,[24] India, Argentina, China, Pakistan, Romania and South Korea).[25]

- Light-water-moderated reactors (LWRs). Light-water reactors (the most common type of thermal reactor) use ordinary water to moderate and cool the reactors.[24] When at operating temperature, if the temperature of the water increases, its density drops, and fewer neutrons passing through it are slowed enough to trigger further reactions. That negative feedback stabilizes the reaction rate. Graphite and heavy-water reactors tend to be more thoroughly thermalized than light water reactors. Due to the extra thermalization, these types can use natural uranium/unenriched fuel.

- Light-element-moderated reactors.

- Molten salt reactors (MSRs) are moderated by light elements such as lithium or beryllium, which are constituents of the coolant/fuel matrix salts LiF and BeF2.

- Liquid metal cooled reactors, such as those whose coolant is a mixture of lead and bismuth, may use BeO as a moderator.

- Organically moderated reactors (OMR) use biphenyl and terphenyl as moderator and coolant.

By coolant

- Water cooled reactor. These constitute the great majority of operational nuclear reactors: as of 2014, 93% of the world's nuclear reactors are water cooled, providing about 95% of the world's total nuclear generation capacity.[22]

- Pressurized water reactor (PWR) Pressurized water reactors constitute the large majority of all Western nuclear power plants.

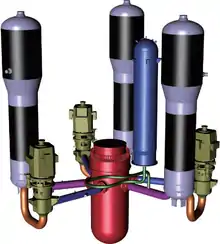

- A primary characteristic of PWRs is a pressurizer, a specialized pressure vessel. Most commercial PWRs and naval reactors use pressurizers. During normal operation, a pressurizer is partially filled with water, and a steam bubble is maintained above it by heating the water with submerged heaters. During normal operation, the pressurizer is connected to the primary reactor pressure vessel (RPV) and the pressurizer "bubble" provides an expansion space for changes in water volume in the reactor. This arrangement also provides a means of pressure control for the reactor by increasing or decreasing the steam pressure in the pressurizer using the pressurizer heaters.

- Pressurized heavy water reactors are a subset of pressurized water reactors, sharing the use of a pressurized, isolated heat transport loop, but using heavy water as coolant and moderator for the greater neutron economies it offers.

- Boiling water reactor (BWR)

- BWRs are characterized by boiling water around the fuel rods in the lower portion of a primary reactor pressure vessel. A boiling water reactor uses 235U, enriched as uranium dioxide, as its fuel. The fuel is assembled into rods housed in a steel vessel that is submerged in water. The nuclear fission causes the water to boil, generating steam. This steam flows through pipes into turbines. The turbines are driven by the steam, and this process generates electricity.[26] During normal operation, pressure is controlled by the amount of steam flowing from the reactor pressure vessel to the turbine.

- Supercritical water reactor (SCWR)

- SCWRs are a Generation IV reactor concept where the reactor is operated at supercritical pressures and water is heated to a supercritical fluid, which never undergoes a transition to steam yet behaves like saturated steam, to power a steam generator.

- Pool-type reactor can refer to open pool reactors which are water cooled, but not to be confused with pool type LMFBRs which are sodium cooled

- Some reactors have been cooled by heavy water which also served as a moderator. Examples include:

- Pressurized water reactor (PWR) Pressurized water reactors constitute the large majority of all Western nuclear power plants.

- Liquid metal cooled reactor. Since water is a moderator, it cannot be used as a coolant in a fast reactor. Liquid metal coolants have included sodium, NaK, lead, lead-bismuth eutectic, and in early reactors, mercury.

- Gas cooled reactors are cooled by a circulating gas. In commercial nuclear power plants carbon dioxide has usually been used, for example in current British AGR nuclear power plants and formerly in a number of first generation British, French, Italian, & Japanese plants. Nitrogen[27] and helium have also been used, helium being considered particularly suitable for high temperature designs. Utilization of the heat varies, depending on the reactor. Commercial nuclear power plants run the gas through a heat exchanger to make steam for a steam turbine. Some experimental designs run hot enough that the gas can directly power a gas turbine.

- Molten salt reactors (MSRs) are cooled by circulating a molten salt, typically a eutectic mixture of fluoride salts, such as FLiBe. In a typical MSR, the coolant is also used as a matrix in which the fissile material is dissolved.

- Organic nuclear reactors use organic fluids such as biphenyl and terphenyl as coolant rather than water.

By generation

- Generation I reactor (early prototypes such as Shippingport Atomic Power Station, research reactors, non-commercial power producing reactors)

- Generation II reactor (most current nuclear power plants, 1965–1996)

- Generation III reactor (evolutionary improvements of existing designs, 1996–present)

- Generation III+ reactor (evolutionary development of Gen III reactors, offering improvements in safety over Gen III reactor designs, 2017–present)[28]

- Generation IV reactor (technologies still under development; unknown start date, possibly 2030)[29]

- Generation V reactors: Reactors that are purely theoretical and are not the subject of intense research.

In 2003, the French Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique (CEA) was the first to refer to "Gen II" types in Nucleonics Week.[30]

The first mention of "Gen III" was in 2000, in conjunction with the launch of the Generation IV International Forum (GIF) plans.

"Gen IV" was named in 2000, by the United States Department of Energy (DOE), for developing new plant types.[31]

By phase of fuel

- Solid fueled

- Fluid fueled

- Gas fueled (theoretical)

By shape of the core

- Cubical

- Cylindrical

- Octagonal

- Spherical

- Slab

- Annulus

By use

- Electricity

- Nuclear power plants including small modular reactors

- Propulsion, see nuclear propulsion

- Nuclear marine propulsion

- Various proposed forms of rocket propulsion

- Other uses of heat

- Desalination

- Heat for domestic and industrial heating

- Hydrogen production for use in a hydrogen economy

- Production reactors for transmutation of elements

- Breeder reactors are capable of producing more fissile material than they consume during the fission chain reaction (by converting fertile U-238 to Pu-239, or Th-232 to U-233). Thus, a uranium breeder reactor, once running, can be refueled with natural or even depleted uranium, and a thorium breeder reactor can be refueled with thorium; however, an initial stock of fissile material is required.[32]

- Creating various radioactive isotopes, such as americium for use in smoke detectors, and cobalt-60, molybdenum-99 and others, used for imaging and medical treatment.

- Production of materials for nuclear weapons such as weapons-grade plutonium

- Providing a source of neutron radiation (for example with the pulsed Godiva device) and positron radiation (e.g. neutron activation analysis and potassium-argon dating)

- Research reactor: Typically reactors used for research and training, materials testing, or the production of radioisotopes for medicine and industry. These are much smaller than power reactors or those propelling ships, and many are on university campuses. There are about 280 such reactors operating, in 56 countries. Some operate with high-enriched uranium fuel, and international efforts are underway to substitute low-enriched fuel.[33]

Current technologies

- Pressurized water reactors (PWR) [moderator: high-pressure water; coolant: high-pressure water]

- These reactors use a pressure vessel to contain the nuclear fuel, control rods, moderator, and coolant. The hot radioactive water that leaves the pressure vessel is looped through a steam generator, which in turn heats a secondary (nonradioactive) loop of water to steam that can run turbines. They represent the majority (around 80%) of current reactors. This is a thermal neutron reactor design, the newest of which are the Russian VVER-1200, Japanese Advanced Pressurized Water Reactor, American AP1000, Chinese Hualong Pressurized Reactor and the Franco-German European Pressurized Reactor. All the United States Naval reactors are of this type.

- Boiling water reactors (BWR) [moderator: low-pressure water; coolant: low-pressure water]

- A BWR is like a PWR without the steam generator. The lower pressure of its cooling water allows it to boil inside the pressure vessel, producing the steam that runs the turbines. Unlike a PWR, there is no primary and secondary loop. The thermal efficiency of these reactors can be higher, and they can be simpler, and even potentially more stable and safe. This is a thermal neutron reactor design, the newest of which are the Advanced Boiling Water Reactor and the Economic Simplified Boiling Water Reactor.

- Pressurized Heavy Water Reactor (PHWR) [moderator: high-pressure heavy water; coolant: high-pressure heavy water]

- A Canadian design (known as CANDU), very similar to PWRs but using heavy water. While heavy water is significantly more expensive than ordinary water, it has greater neutron economy (creates a higher number of thermal neutrons), allowing the reactor to operate without fuel enrichment facilities. Instead of using a single large pressure vessel as in a PWR, the fuel is contained in hundreds of pressure tubes. These reactors are fueled with natural uranium and are thermal neutron reactor designs. PHWRs can be refueled while at full power, which makes them very efficient in their use of uranium (it allows for precise flux control in the core). CANDU PHWRs have been built in Canada, Argentina, China, India, Pakistan, Romania, and South Korea. India also operates a number of PHWRs, often termed 'CANDU derivatives', built after the Government of Canada halted nuclear dealings with India following the 1974 Smiling Buddha nuclear weapon test.

The Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant — a RBMK type (closed 2009)

The Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant — a RBMK type (closed 2009)

- Reaktor Bolshoy Moschnosti Kanalniy (High Power Channel Reactor) (RBMK) [moderator: graphite; coolant: high-pressure water]

- A Soviet design, RBMKs are in some respects similar to CANDU in that they are refuelable during power operation and employ a pressure tube design instead of a PWR-style pressure vessel. However, unlike CANDU they are very unstable and large, making containment buildings for them expensive. A series of critical safety flaws have also been identified with the RBMK design, though some of these were corrected following the Chernobyl disaster. Their main attraction is their use of light water and unenriched uranium. As of 2021, 9 remain open, mostly due to safety improvements and help from international safety agencies such as the DOE. Despite these safety improvements, RBMK reactors are still considered one of the most dangerous reactor designs in use. RBMK reactors were deployed only in the former Soviet Union.

- Gas-cooled reactor (GCR) and advanced gas-cooled reactor (AGR) [moderator: graphite; coolant: carbon dioxide]

- These designs an have a high thermal efficiency compared with PWRs due to higher operating temperatures. There are a number of operating reactors of this design, mostly in the United Kingdom, where the concept was developed. Older designs (i.e. Magnox stations) are either shut down or will be in the near future. However, the AGRs have an anticipated life of a further 10 to 20 years. This is a thermal neutron reactor design. Decommissioning costs can be high due to large volume of reactor core.

- Liquid metal fast-breeder reactor (LMFBR) [moderator: none; coolant: liquid metal]

- This totally unmoderated reactor design produces more fuel than it consumes. They are said to "breed" fuel, because they produce fissionable fuel during operation because of neutron capture. These reactors can function much like a PWR in terms of efficiency, and do not require much high-pressure containment, as the liquid metal does not need to be kept at high pressure, even at very high temperatures. These reactors are fast neutron, not thermal neutron designs. These reactors come in two types:

- Lead-cooled

- Using lead as the liquid metal provides excellent radiation shielding, and allows for operation at very high temperatures. Also, lead is (mostly) transparent to neutrons, so fewer neutrons are lost in the coolant, and the coolant does not become radioactive. Unlike sodium, lead is mostly inert, so there is less risk of explosion or accident, but such large quantities of lead may be problematic from toxicology and disposal points of view. Often a reactor of this type would use a lead-bismuth eutectic mixture. In this case, the bismuth would present some minor radiation problems, as it is not quite as transparent to neutrons, and can be transmuted to a radioactive isotope more readily than lead. The Russian Alfa class submarine uses a lead-bismuth-cooled fast reactor as its main power plant.

- Sodium-cooled

- Most LMFBRs are of this type. The TOPAZ, BN-350 and BN-600 in USSR; Superphénix in France; and Fermi-I in the United States were reactors of this type. The sodium is relatively easy to obtain and work with, and it also manages to actually prevent corrosion on the various reactor parts immersed in it. However, sodium explodes violently when exposed to water, so care must be taken, but such explosions would not be more violent than (for example) a leak of superheated fluid from a pressurized-water reactor. The Monju reactor in Japan suffered a sodium leak in 1995 and could not be restarted until May 2010. The EBR-I, the first reactor to have a core meltdown, in 1955, was also a sodium-cooled reactor.

- Lead-cooled

- Pebble-bed reactors (PBR) [moderator: graphite; coolant: helium]

- These use fuel molded into ceramic balls, and then circulate gas through the balls. The result is an efficient, low-maintenance, very safe reactor with inexpensive, standardized fuel. The prototype was the AVR and the HTR-10 is operating in China, where the HTR-PM is being developed. The HTR-PM is expected to be the first generation IV reactor to enter operation.[34]

- Molten salt reactors (MSR) [moderator: graphite; coolant: molten salt mixture]

- These dissolve the fuels in fluoride salts, or use fluoride salts for coolant. These have many safety features, high efficiency and a high power density suitable for vehicles. Notably, they have no high pressures or flammable components in the core. The prototype was the MSRE, which also used the Thorium fuel cycle. As a breeder reactor type, it reprocesses the spent fuel, extracting both Uranium and transuranics, leaving only 0.1% of transuranic waste compared to conventional once-through uranium-fueled light water reactors currently in use. A separate issue is the radioactive fission products, which are not reprocessable and need to be disposed of as with conventional reactors.

- Aqueous Homogeneous Reactor (AHR) [moderator: high-pressure light or heavy water; coolant: high-pressure light or heavy water]

- These reactors use as fuel soluble nuclear salts (usually uranium sulfate or uranium nitrate) dissolved in water and mixed with the coolant and the moderator. As of April 2006, only five AHRs were in operation.[35]

Advanced reactors

More than a dozen advanced reactor designs are in various stages of development.[36] Some are evolutionary from the PWR, BWR and PHWR designs above, some are more radical departures. The former include the advanced boiling water reactor (ABWR), two of which are now operating with others under construction, and the planned passively safe Economic Simplified Boiling Water Reactor (ESBWR) and AP1000 units (see Nuclear Power 2010 Program).

- The Integral fast reactor (IFR) was built, tested and evaluated during the 1980s and then retired under the Clinton administration in the 1990s due to nuclear non-proliferation policies of the administration. Recycling spent fuel is the core of its design and it therefore produces only a fraction of the waste of current reactors.[37]

- The pebble-bed reactor, a high-temperature gas-cooled reactor (HTGCR), is designed so high temperatures reduce power output by Doppler broadening of the fuel's neutron cross-section. It uses ceramic fuels so its safe operating temperatures exceed the power-reduction temperature range. Most designs are cooled by inert helium. Helium is not subject to steam explosions, resists neutron absorption leading to radioactivity, and does not dissolve contaminants that can become radioactive. Typical designs have more layers (up to 7) of passive containment than light water reactors (usually 3). A unique feature that may aid safety is that the fuel balls actually form the core's mechanism, and are replaced one by one as they age. The design of the fuel makes fuel reprocessing expensive.

- The Small, sealed, transportable, autonomous reactor (SSTAR) is being primarily researched and developed in the US, intended as a fast breeder reactor that is passively safe and could be remotely shut down in case the suspicion arises that it is being tampered with.

- The Clean and Environmentally Safe Advanced Reactor (CAESAR) is a nuclear reactor concept that uses steam as a moderator – this design is still in development.

- The Reduced moderation water reactor builds upon the Advanced boiling water reactor(ABWR) that is presently in use, it is not a complete fast reactor instead using mostly epithermal neutrons, which are between thermal and fast neutrons in speed.

- The hydrogen-moderated self-regulating nuclear power module (HPM) is a reactor design emanating from the Los Alamos National Laboratory that uses uranium hydride as fuel.

- Subcritical reactors are designed to be safer and more stable, but pose a number of engineering and economic difficulties. One example is the Energy amplifier.

- Thorium-based reactors. It is possible to convert Thorium-232 into U-233 in reactors specially designed for the purpose. In this way, thorium, which is four times more abundant than uranium, can be used to breed U-233 nuclear fuel.[38] U-233 is also believed to have favourable nuclear properties as compared to traditionally used U-235, including better neutron economy and lower production of long lived transuranic waste.

- Advanced heavy-water reactor (AHWR)— A proposed heavy water moderated nuclear power reactor that will be the next generation design of the PHWR type. Under development in the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), India.

- KAMINI — A unique reactor using Uranium-233 isotope for fuel. Built in India by BARC and Indira Gandhi Center for Atomic Research (IGCAR).

- India is also planning to build fast breeder reactors using the thorium – Uranium-233 fuel cycle. The FBTR (Fast Breeder Test Reactor) in operation at Kalpakkam (India) uses Plutonium as a fuel and liquid sodium as a coolant.

- China, which has control of the Cerro Impacto deposit, has a reactor and hopes to replace coal energy with nuclear energy.[39]

Rolls-Royce aims to sell nuclear reactors for the production of synfuel for aircraft.[40]

Generation IV reactors

Generation IV reactors are a set of theoretical nuclear reactor designs currently being researched. These designs are generally not expected to be available for commercial construction before 2030. Current reactors in operation around the world are generally considered second- or third-generation systems, with the first-generation systems having been retired some time ago. Research into these reactor types was officially started by the Generation IV International Forum (GIF) based on eight technology goals. The primary goals being to improve nuclear safety, improve proliferation resistance, minimize waste and natural resource utilization, and to decrease the cost to build and run such plants.[41]

Generation V+ reactors

Generation V reactors are designs which are theoretically possible, but which are not being actively considered or researched at present. Though some generation V reactors could potentially be built with current or near term technology, they trigger little interest for reasons of economics, practicality, or safety.

- Liquid-core reactor. A closed loop liquid-core nuclear reactor, where the fissile material is molten uranium or uranium solution cooled by a working gas pumped in through holes in the base of the containment vessel.

- Gas-core reactor. A closed loop version of the nuclear lightbulb rocket, where the fissile material is gaseous uranium hexafluoride contained in a fused silica vessel. A working gas (such as hydrogen) would flow around this vessel and absorb the UV light produced by the reaction. This reactor design could also function as a rocket engine, as featured in Harry Harrison's 1976 science-fiction novel Skyfall. In theory, using UF6 as a working fuel directly (rather than as a stage to one, as is done now) would mean lower processing costs, and very small reactors. In practice, running a reactor at such high power densities would probably produce unmanageable neutron flux, weakening most reactor materials, and therefore as the flux would be similar to that expected in fusion reactors, it would require similar materials to those selected by the International Fusion Materials Irradiation Facility.

- Gas core EM reactor. As in the gas core reactor, but with photovoltaic arrays converting the UV light directly to electricity.[42] This approach is similar to the experimentally proved photoelectric effect that would convert the X-rays generated from aneutronic fusion into electricity, by passing the high energy photons through an array of conducting foils to transfer some of their energy to electrons, the energy of the photon is captured electrostatically, similar to a capacitor. Since X-rays can go through far greater material thickness than electrons, many hundreds or thousands of layers are needed to absorb the X-rays.[43]

- Fission fragment reactor. A fission fragment reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates electricity by decelerating an ion beam of fission byproducts instead of using nuclear reactions to generate heat. By doing so, it bypasses the Carnot cycle and can achieve efficiencies of up to 90% instead of 40–45% attainable by efficient turbine-driven thermal reactors. The fission fragment ion beam would be passed through a magnetohydrodynamic generator to produce electricity.

- Hybrid nuclear fusion. Would use the neutrons emitted by fusion to fission a blanket of fertile material, like U-238 or Th-232 and transmute other reactor's spent nuclear fuel/nuclear waste into relatively more benign isotopes.

Fusion reactors

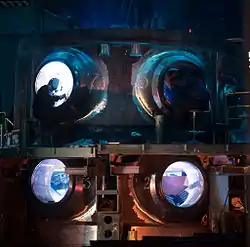

Controlled nuclear fusion could in principle be used in fusion power plants to produce power without the complexities of handling actinides, but significant scientific and technical obstacles remain. Several fusion reactors have been built, but only recently reactors have been able to release more energy than the amount of energy used in the process. Despite research having started in the 1950s, no commercial fusion reactor is expected before 2050. The ITER project is currently leading the effort to harness fusion power.

Nuclear fuel cycle

Thermal reactors generally depend on refined and enriched uranium. Some nuclear reactors can operate with a mixture of plutonium and uranium (see MOX). The process by which uranium ore is mined, processed, enriched, used, possibly reprocessed and disposed of is known as the nuclear fuel cycle.

Under 1% of the uranium found in nature is the easily fissionable U-235 isotope and as a result most reactor designs require enriched fuel. Enrichment involves increasing the percentage of U-235 and is usually done by means of gaseous diffusion or gas centrifuge. The enriched result is then converted into uranium dioxide powder, which is pressed and fired into pellet form. These pellets are stacked into tubes which are then sealed and called fuel rods. Many of these fuel rods are used in each nuclear reactor.

Most BWR and PWR commercial reactors use uranium enriched to about 4% U-235, and some commercial reactors with a high neutron economy do not require the fuel to be enriched at all (that is, they can use natural uranium). According to the International Atomic Energy Agency there are at least 100 research reactors in the world fueled by highly enriched (weapons-grade/90% enrichment) uranium. Theft risk of this fuel (potentially used in the production of a nuclear weapon) has led to campaigns advocating conversion of this type of reactor to low-enrichment uranium (which poses less threat of proliferation).[44]

Fissile U-235 and non-fissile but fissionable and fertile U-238 are both used in the fission process. U-235 is fissionable by thermal (i.e. slow-moving) neutrons. A thermal neutron is one which is moving about the same speed as the atoms around it. Since all atoms vibrate proportionally to their absolute temperature, a thermal neutron has the best opportunity to fission U-235 when it is moving at this same vibrational speed. On the other hand, U-238 is more likely to capture a neutron when the neutron is moving very fast. This U-239 atom will soon decay into plutonium-239, which is another fuel. Pu-239 is a viable fuel and must be accounted for even when a highly enriched uranium fuel is used. Plutonium fissions will dominate the U-235 fissions in some reactors, especially after the initial loading of U-235 is spent. Plutonium is fissionable with both fast and thermal neutrons, which make it ideal for either nuclear reactors or nuclear bombs.

Most reactor designs in existence are thermal reactors and typically use water as a neutron moderator (moderator means that it slows down the neutron to a thermal speed) and as a coolant. But in a fast breeder reactor, some other kind of coolant is used which will not moderate or slow the neutrons down much. This enables fast neutrons to dominate, which can effectively be used to constantly replenish the fuel supply. By merely placing cheap unenriched uranium into such a core, the non-fissionable U-238 will be turned into Pu-239, "breeding" fuel.

In thorium fuel cycle thorium-232 absorbs a neutron in either a fast or thermal reactor. The thorium-233 beta decays to protactinium-233 and then to uranium-233, which in turn is used as fuel. Hence, like uranium-238, thorium-232 is a fertile material.

Fueling of nuclear reactors

The amount of energy in the reservoir of nuclear fuel is frequently expressed in terms of "full-power days," which is the number of 24-hour periods (days) a reactor is scheduled for operation at full power output for the generation of heat energy. The number of full-power days in a reactor's operating cycle (between refueling outage times) is related to the amount of fissile uranium-235 (U-235) contained in the fuel assemblies at the beginning of the cycle. A higher percentage of U-235 in the core at the beginning of a cycle will permit the reactor to be run for a greater number of full-power days.

At the end of the operating cycle, the fuel in some of the assemblies is "spent", having spent 4 to 6 years in the reactor producing power. This spent fuel is discharged and replaced with new (fresh) fuel assemblies. Though considered "spent," these fuel assemblies contain a large quantity of fuel. In practice it is economics that determines the lifetime of nuclear fuel in a reactor. Long before all possible fission has taken place, the reactor is unable to maintain 100%, full output power, and therefore, income for the utility lowers as plant output power lowers. Most nuclear plants operate at a very low profit margin due to operating overhead, mainly regulatory costs, so operating below 100% power is not economically viable for very long. The fraction of the reactor's fuel core replaced during refueling is typically one-third, but depends on how long the plant operates between refueling. Plants typically operate on 18 month refueling cycles, or 24 month refueling cycles. This means that 1 refueling, replacing only one-third of the fuel, can keep a nuclear reactor at full power for nearly 2 years. The disposition and storage of this spent fuel is one of the most challenging aspects of the operation of a commercial nuclear power plant. This nuclear waste is highly radioactive and its toxicity presents a danger for thousands of years.[26] After being discharged from the reactor, spent nuclear fuel is transferred to the on-site spent fuel pool. The spent fuel pool is a large pool of water that provides cooling and shielding of the spent nuclear fuel. Once the energy has decayed somewhat (approximately 5 years), the fuel can be transferred from the fuel pool to dry shielded casks, that can be safely stored for thousands of years. After loading into dry shielded casks, the casks are stored on-site in a specially guarded facility in impervious concrete bunkers. On-site fuel storage facilities are designed to withstand the impact of commercial airliners, with little to no damage to the spent fuel. An average on-site fuel storage facility can hold 30 years of spent fuel in a space smaller that a football field.

Not all reactors need to be shut down for refueling; for example, pebble bed reactors, RBMK reactors, molten salt reactors, Magnox, AGR and CANDU reactors allow fuel to be shifted through the reactor while it is running. In a CANDU reactor, this also allows individual fuel elements to be situated within the reactor core that are best suited to the amount of U-235 in the fuel element.

The amount of energy extracted from nuclear fuel is called its burnup, which is expressed in terms of the heat energy produced per initial unit of fuel weight. Burn up is commonly expressed as megawatt days thermal per metric ton of initial heavy metal.

Nuclear safety

Nuclear safety covers the actions taken to prevent nuclear and radiation accidents and incidents or to limit their consequences. The nuclear power industry has improved the safety and performance of reactors, and has proposed new, safer (but generally untested) reactor designs but there is no guarantee that the reactors will be designed, built and operated correctly.[45] Mistakes do occur and the designers of reactors at Fukushima in Japan did not anticipate that a tsunami generated by an earthquake would disable the backup systems that were supposed to stabilize the reactor after the earthquake,[46] despite multiple warnings by the NRG and the Japanese nuclear safety administration. According to UBS AG, the Fukushima I nuclear accidents have cast doubt on whether even an advanced economy like Japan can master nuclear safety.[47] Catastrophic scenarios involving terrorist attacks are also conceivable.[45] An interdisciplinary team from MIT has estimated that given the expected growth of nuclear power from 2005 to 2055, at least four serious nuclear accidents would be expected in that period.[48]

Nuclear accidents

Serious, though rare, nuclear and radiation accidents have occurred. These include the SL-1 accident (1961), the Three Mile Island accident (1979), Chernobyl disaster (1986), and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (2011). Nuclear-powered submarine mishaps include the K-19 reactor accident (1961),[51] the K-27 reactor accident (1968),[52] and the K-431 reactor accident (1985).

Nuclear reactors have been launched into Earth orbit at least 34 times. A number of incidents connected with the unmanned nuclear-reactor-powered Soviet RORSAT radar satellite program resulted in spent nuclear fuel reentering the Earth's atmosphere from orbit.

Natural nuclear reactors

Almost two billion years ago a series of self-sustaining nuclear fission "reactors" self-assembled in the area now known as Oklo in Gabon, West Africa. The conditions at that place and time allowed a natural nuclear fission to occur with circumstances that are similar to the conditions in a constructed nuclear reactor. [53] Fifteen fossil natural fission reactors have so far been found in three separate ore deposits at the Oklo uranium mine in Gabon. First discovered in 1972 by French physicist Francis Perrin, they are collectively known as the Oklo Fossil Reactors. Self-sustaining nuclear fission reactions took place in these reactors approximately 1.5 billion years ago, and ran for a few hundred thousand years, averaging 100 kW of power output during that time.[54] The concept of a natural nuclear reactor was theorized as early as 1956 by Paul Kuroda at the University of Arkansas.[55][56]

Such reactors can no longer form on Earth in its present geologic period. Radioactive decay of formerly more abundant uranium-235 over the time span of hundreds of millions of years has reduced the proportion of this naturally occurring fissile isotope to below the amount required to sustain a chain reaction with only plain water as a moderator.

The natural nuclear reactors formed when a uranium-rich mineral deposit became inundated with groundwater that acted as a neutron moderator, and a strong chain reaction took place. The water moderator would boil away as the reaction increased, slowing it back down again and preventing a meltdown. The fission reaction was sustained for hundreds of thousands of years, cycling on the order of hours to a few days.

These natural reactors are extensively studied by scientists interested in geologic radioactive waste disposal. They offer a case study of how radioactive isotopes migrate through the Earth's crust. This is a significant area of controversy as opponents of geologic waste disposal fear that isotopes from stored waste could end up in water supplies or be carried into the environment.

Emissions

Nuclear reactors produce tritium as part of normal operations, which is eventually released into the environment in trace quantities.

As an isotope of hydrogen, tritium (T) frequently binds to oxygen and forms T2O. This molecule is chemically identical to H2O and so is both colorless and odorless, however the additional neutrons in the hydrogen nuclei cause the tritium to undergo beta decay with a half-life of 12.3 years. Despite being measurable, the tritium released by nuclear power plants is minimal. The United States NRC estimates that a person drinking water for one year out of a well contaminated by what they would consider to be a significant tritiated water spill would receive a radiation dose of 0.3 millirem.[57] For comparison, this is an order of magnitude less than the 4 millirem a person receives on a round trip flight from Washington, D.C. to Los Angeles, a consequence of less atmospheric protection against highly energetic cosmic rays at high altitudes.[57]

The amounts of strontium-90 released from nuclear power plants under normal operations is so low as to be undetectable above natural background radiation. Detectable strontium-90 in ground water and the general environment can be traced to weapons testing that occurred during the mid-20th century (accounting for 99% of the Strontium-90 in the environment) and the Chernobyl accident (accounting for the remaining 1%).[58]

See also

- List of nuclear reactors

- List of small modular reactor designs

- List of United States Naval reactors

- Neutron transport

- Nuclear power by country

- Nuclear power in space

- One Less Nuclear Power Plant

- Radioisotope thermoelectric generator

- Safety engineering

- Sayonara Nuclear Power Plants

- Small modular reactor

- Thorium-based nuclear power

- Traveling-wave reactor (TWR)

- World Nuclear Industry Status Report

References

- "PRIS – Home". pris.iaea.org.

- "RRDB Search". nucleus.iaea.org.

- Oldekop, W. (1982), "Electricity and Heat from Thermal Nuclear Reactors", Primary Energy, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 66–91, ISBN 978-3-540-11307-2, retrieved 2 February 2021

- "DOE Fundamentals Handbook: Nuclear Physics and Reactor Theory" (PDF). US Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- "Reactor Protection & Engineered Safety Feature Systems". The Nuclear Tourist. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- "Bioenergy Conversion Factors". Bioenergy.ornl.gov. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- Bernstein, Jeremy (2008). Nuclear Weapons: What You Need to Know. Cambridge University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-521-88408-2. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "How nuclear power works". HowStuffWorks.com. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- "Reactor Protection & Engineered Safety Feature Systems". The Nuclear Tourist. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- "Chernobyl: what happened and why? by CM Meyer, technical journalist" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2013.

- Tsetkov, Pavel; Usman, Shoaib (2011). Krivit, Steven (ed.). Nuclear Energy Encyclopedia: Science, Technology, and Applications. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 48, 85. ISBN 978-0-470-89439-2.

- L. Szilárd, "Improvements in or relating to the transmutation of chemical elements," British patent number: GB630726 (filed: 28 June 1934; published: 30 March 1936).

- The First Reactor, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Division of Technical Information

- Enrico, Fermi and Leo, Szilard U.S. Patent 2,708,656 "Neutronic Reactor" issued 17 May 1955

- "Chicago Pile reactors create enduring research legacy – Argonne's Historical News Releases". anl.gov.

- Experimental Breeder Reactor 1 factsheet, Idaho National Laboratory Archived 29 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Fifty years ago in December: Atomic reactor EBR-I produced first electricity" (PDF). American Nuclear Society Nuclear news. November 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- "The Nuclear Option — NOVA | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- Kragh, Helge (1999). Quantum Generations: A History of Physics in the Twentieth Century. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 286. ISBN 0-691-09552-3.

- "On This Day: 17 October". BBC News. 17 October 1956. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- Leskovitz, Frank J. "Science Leads the Way". Camp Century, Greenland.

- "Nuclear Power Reactors in the World – 2015 Edition" (PDF). International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- Golubev, V. I.; Dolgov, V. V.; Dulin, V. A.; Zvonarev, A. V.; Smetanin, É. Y.; Kochetkov, L. A.; Korobeinikov, V. V.; Liforov, V. G.; Manturov, G. N.; Matveenko, I. P.; Tsibulya, A. M. (1993). "Fast-reactor actinoid transmutation". Atomic Energy. 74: 83. doi:10.1007/BF00750983. S2CID 95704617.

- Nave, R. "Light Water Nuclear Reactors". Hyperphysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Joyce, Malcolm (2018). "10.6". Nuclear Engineering. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/c2015-0-05557-5. ISBN 9780081009628.

- Lipper, Ilan; Stone, Jon. "Nuclear Energy and Society". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- "Emergency and Back-Up Cooling of Nuclear Fuel and Reactors and Fire-Extinguishing, Explosion Prevention Using Liquid Nitrogen". USPTO Patent Applications. Document number 20180144836. 24 May 2018.

- "Russia completes world's first Gen III+ reactor; China to start up five reactors in 2017". Nuclear Energy Insider. 8 February 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "Generation IV Nuclear Reactors". World Nuclear Association.

- Nucleonics Week, Vol. 44, No. 39; p. 7, 25 September 2003 Quote: "Etienne Pochon, CEA director of nuclear industry support, outlined EPR's improved performance and enhanced safety features compared to the advanced Generation II designs on which it was based."

- "Generation IV". Euronuclear.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- "A Technology Roadmap for Generation IV Nuclear Energy Systems" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2006. (4.33 MB); see "Fuel Cycles and Sustainability"

- "World Nuclear Association Information Brief -Research Reactors". Archived from the original on 31 December 2006.

- "HTR-PM: Making dreams come true". Nuclear Engineering International.

- "RRDB Search". nucleus.iaea.org.

- "Advanced Nuclear Power Reactors". World Nuclear Association. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- Till, Charles. "Nuclear Reaction: Why Do Americans Fear Nuclear Power?". Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- Juhasz, Albert J.; Rarick, Richard A.; Rangarajan, Rajmohan. "High Efficiency Nuclear Power Plants Using Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactor Technology" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "The Venezuela-China relationship, explained: Belt and Road | Part 2 of 4". SupChina. 14 January 2019. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- https://www.bloomberg.com/amp/news/articles/2019-12-06/rolls-royce-pitches-nuclear-reactors-as-key-to-clean-jet-fuel

- "Generation IV Nuclear Reactors". World Nuclear Association. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- "International Scientific Journal for Alternative Energy and Ecology, DIRECT CONVERSION OF NUCLEAR ENERGY TO ELECTRICITY, Mark A. Prelas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Quimby, D.C., High Thermal Efficiency X-ray energy conversion scheme for advanced fusion reactors, ASTM Special technical Publication, v.2, 1977, pp. 1161–1165

- "Improving Security at World's Nuclear Research Reactors: Technical and Other Issues Focus of June Symposium in Norway". IAEA. 7 June 2006.

- Jacobson, Mark Z. & Delucchi, Mark A. (2010). "Providing all Global Energy with Wind, Water, and Solar Power, Part I: Technologies, Energy Resources, Quantities and Areas of Infrastructure, and Materials" (PDF). Energy Policy. p. 6.

- Gusterson, Hugh (16 March 2011). "The lessons of Fukushima". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013.

- Paton, James (4 April 2011). "Fukushima Crisis Worse for Atomic Power Than Chernobyl, UBS Says". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011.

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2003). "The Future of Nuclear Power" (PDF). p. 48.

- Fackler, Martin (1 June 2011). "Report Finds Japan Underestimated Tsunami Danger". The New York Times.

- Strengthening the Safety of Radiation Sources p. 14.

- Johnston, Robert (23 September 2007). "Deadliest radiation accidents and other events causing radiation casualties". Database of Radiological Incidents and Related Events.

- Video of physics lecture – at Google Video; a natural nuclear reactor is mentioned at 42:40 mins into the video Archived 4 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Meshik, Alex P. (November 2005) "The Workings of an Ancient Nuclear Reactor." Scientific American. p. 82.

- "Oklo: Natural Nuclear Reactors". Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management. Archived from the original on 16 March 2006. Retrieved 28 June 2006.

- "Oklo's Natural Fission Reactors". American Nuclear Society. Retrieved 28 June 2006.

- Backgrounder: Tritium, Radiation Protection Limits, and Drinking Water Standards (PDF) (Report). United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission. February 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Radionuclides in Groundwater". U.S. NRC. nrc.gov. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuclear reactors. |

- The Database on Nuclear Power Reactors – IAEA

- Uranium Conference adds discussion of Japan accident

- A Debate: Is Nuclear Power The Solution to Global Warming?

- Union of Concerned Scientists, Concerns re: US nuclear reactor program

- Freeview Video 'Nuclear Power Plants — What's the Problem' A Royal Institution Lecture by John Collier by the Vega Science Trust.

- Nuclear Energy Institute — How it Works: Electric Power Generation

- Annotated bibliography of nuclear reactor technology from the Alsos Digital Library

- (in Japanese) ソヴィエト連邦における宇宙用原子炉の開発とその実用