Waterloo Park, Norwich

Waterloo Park is a public park located in Norwich. Dating from 1904, the current park forms one of a set of public parks established in Norwich in the 1930s by Captain Arnold Sandys-Winsch, built by unemployed men using government funding. When the park was re-opened in 1933, it was considered to be the finest in East Anglia, with a pavilion in the style of Moderne architecture, a bandstand, sports facilities, gardens and a children's playground as part of its design. The herbaceous border is one of the longest in the United Kingdom located within a public space.

| Waterloo Park | |

|---|---|

The main pedestrian entrance | |

| |

| Type | public |

| Location | Angel Road, Norwich, Norfolk, UK |

| Coordinates | 52.6457°N 1.2892°E |

| Area | 18 acres (7.3 ha)[1] |

| Created | 1904 (redesigned park opened in 1933)[1] |

| Designer | Captain Arnold Sandys-Winsch[1] |

| Operated by | Norwich City Council[1] |

| Open | daylight hours |

| Status | Grade II* listed[1] |

| Parking | free |

The layout Waterloo Park has remained largely unaltered since the 1930s, although changes have since then been made to the original children's garden, the bowling greens and most of the grass tennis courts, all of which are not used for their original purpose. Following years of relative neglect, the park's main buildings were restored in 2000, and the long-closed pavilion was reopened as a café in 2017. The park is maintained by Norwich City Council.

History

Waterloo Park owes its existence to the work of the Norwich Playing Fields and Open Spaces Society, which saw how the urban population in the Angel Road area of Norwich was increasing rapidly, and so worked with the city authorities to preserve land for use as a recreational space.[2] A plot of land owned by the Great Hospital Trust, surrounded by housing, was leased to the city in 1899. A new park, known as the Catton Recreation Ground, and which was designed to include gardens created by local schoolchildren, was opened in May 1904.[3] In 1911, a proposal was made by the manufacturer Edwards & Holmes to build a shoe factory on land at Waterloo Park, an idea which never materialised.[4]

Catton Recreation Ground was completely redesigned in 1929 by Captain Arnold Sandys-Winsch, originally from Cheshire, who had been appointed as the Norwich City Parks and Gardens Superintendent in 1919. With government funding provided to give temporary relief for unemployed local men, work on the new park was able to start. At 18 acres (7.3 ha), it was the second largest of a series of parks laid out by Sandys-Winsch in Norwich.[1] Completed and opened to the public in 1933, it was the last of Sandys-Winsch's parks to be built, at a cost of £37,000,[5][6] and was "considered to be one of the finest in East Anglia".[1][7] By the time he had retired in 1956,[6] Sandys-Winsch had helped to create 600 acres (240 ha) of urban parks and open spaces in Norwich, and was instrumental in the planting of 20,000 trees in the city.[8]

The central pavilion in Waterloo Park was used as a temporary mortuary during the Second World War. After one air raid, the bodies of factory workers from across the other side of Norwich arrived at the park under police escort, to the horror of people using the nearby tennis courts, who had been unaware of the raid that had happened.[9]

Waterloo Park and its pavilion, pagodas, bandstand and front gates are historically important, and have all been designated as Grade II* listed structures, due to the park being considered to be a good example of an early twentieth century municipal park. The overall layout has remained largely unchanged since the 1930s.[1] Since the 1960s, some of the facilities have been modified, so that original features such as the school garden at the northern tip of the park, and the moat around the edge of the central garden, no longer exist.[10] The park has been recognised by Norwich City Council as an 'historic landscape'.[11] In 1962, £1000 was spent by the council in renovating the pavilion, an expense which was criticized by the local press at the time.[9]

Recent history

The work done by the Countryside Commission in the early 1970s failed to provide for the needs of urban parks in the UK, and after losing its permanent team of dedicated staff, the buildings and landscape within Waterloo Park started to deteriorate.[12] Vandalism and neglect have led to the bowling greens and their pavilions being abandoned.[7] The park was amongst the earliest to be placed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England, when it was included on the list in 1993.[13] In 2000, Norwich City Council was amongst the first recipients to succeed in obtaining funds from the Urban Parks Programme of the Heritage Lottery Fund to restore its historic parks. It used part of the £5.6 million it received to restore Waterloo Park's pavilion and many of its facilities.[7][14]

In 2015, Norwich City Council resolved to deal with problems with the water-damaged roof of the pavilion by spending £210,000 on repairs that year, and £40,000 during 2016/17.[15] In 2017, after the main repairs had been completed, the restored pavilion was reopened as a café, as part of an enterprise to assist low-risk prisoners and ex-offenders to gain work experience.[16] Working in partnership with the council, Britannia Enterprises planned to help maintain and restore the park as well as run the café. The café was forced to close in January 2020.[17][18]

In 2018 the Friends of Waterloo Park was set up, with the initial aim of bringing more sporting opportunities, children's activities and live music to the park.[19] The park was included in the city council's tree planting list for 2018–19, to include the planting of examples of trees that included silver birch, Himalayan birch, Davidia involucrata and southern magnolia.[20]

Facilities

Representing, according to George Ismael of Norwich City Council, "the last phase of municipal park building in Britain", Waterloo Park has been described as having "stylistic unity" with Norwich's other historic public spaces, and a design that "displays a sensitive response to the [surrounding] landscape".[6][12] Everywhere in the park can be accessed by disabled visitors. There are 6 acres (2.4 ha) of gardens, which are dominated by the bandstand and the Art Deco central pavilion. The park also has a children's playground, tennis courts, and open areas once used to play cricket and hockey, as well as toilet facilities.[21][22] The pavilion, bandstand, pagodas, steps and walls are all built from a form of reconstituted stone which looks realistically natural.[23]

The park has one of the country's largest herbaceous borders.[24] The flowerbeds, which once contained roses and annuals that were very expensive to maintain, now have plants that can be sustained ecologically, as they are perennials. According to Ismail, this type of planting is a return to the ideas of the gardener William Robinson and the horticulturist Gertrude Jekyll, and is "completely at one with the period during which the [Norwich] parks were created".[25]

Location and access

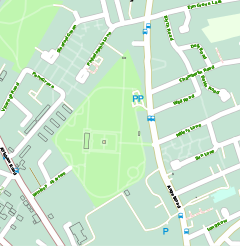

The park, which is approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Norwich city centre, is bounded on the east by Angel Road. Further west from the western boundary of the park is Aylsham Road (the A1402). To the south is Angel Road Infant School and Philadelphia lies to the north.[26] It is normally locked during hours of darkness, but does not close before 5:30pm between October and February.[27] There is free parking, accessed from Angel Road, and two bus routes from the city centre pass nearby.[28]

References

- "Waterloo Park". Historic England. 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Anderson & Cocke 2000, p. 45.

- Anderson & Cocke 2000, p. 46.

- "Papers for a proposed shoe factory at Waterloo Park on land belonging to the Great Hospital". NROCAT. Norfolk Record Office. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- Anderson & Cocke 2000, p. 15, 46.

- Ismail 1998, p. 20.

- Fieldhouse & Woodstra 2000, p. 49.

- Anderson & Cocke 2000, p. 15.

- Anderson & Cocke 2000, p. 49.

- "Waterloo Park". Norfolk Heritage Explorer. Norfolk County Council. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Rawcliffe & Wilson 2004, p. 33.

- Anderson & Cocke 2000, p. 65.

- Ismail 1998, p. 21.

- Ismail 1998, pp. 21-22.

- Grimmer, Dan (29 February 2016). "Work still hasn't started on Norwich's Waterloo Park Pavilion - a year after cash was found". Eastern Daily Press. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Knights, Emma (27 October 2017). "New café opens in the pavilion of Norwich's Waterloo Park". Eastern Daily Press. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Cope, Lauren (22 January 2020). "Café in city park forced to close". Eastern Daily Press. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Grimmer, Dan (13 June 2017). "Pavilion in Norwich's Waterloo Park to be turned into a cafe". Eastern Daily Press. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Wyllie, Sophie (26 May 2018). "New volunteer friends group promises to enhance and protect popular park". Eastern Daily Press. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "Tree planting list 2018-19". Norwich City Council. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Meeres 1998, p. 214.

- Rawcliffe & Wilson 2004, p. 333.

- Anderson & Cocke 2000, p. 50.

- "Waterloo Park". Parks & Gardens. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Ismail 1998, p. 24.

- "Waterloo Park". Bing Maps. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- "Parks closing times". Norwich City Council. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- "Norwich bus routes" (PDF). Network Norwich. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

Sources

- Anderson, A.P.; Cocke, Sarah (2000). The captain and the Norwich parks. The Norwich Society. ISBN 978-0-9524756-1-3.

- Fieldhouse, Ken; Woodstra, Jan, eds. (2000). The Regeneration of Public Parks. London and New York: E & FN Spon. ISBN 978-0-419-25900-8.

- Ismail, George (Spring 1998). Clarke, Ethna (ed.). "The Norwich Parks". Norfolk Gardens Trust Journal.

- Meeres, Frank (1998). A History of Norwich. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86077-083-8.

- Rawcliffe, Carole; Wilson, Richard, eds. (2004). Norwich Since 1550. London and New York: Hambleton and London. ISBN 978-1-85285-450-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Waterloo Park, Norwich. |

- Information about Waterloo Park (Norwich City Council)

- Pictures (with captions) of the park dating back to the 1950s, from the Eastern Daily Press

- Further information about Captain Arnold Edward Sandys-Winsch and Norwich's city parks from the Colonel Unthank's Norwich website

- Images of Norwich's parks and gardens from George Plunkett's Photographs, including 5 photographs of Waterloo Park that were taken on 30 April 1933, the day after the new park opened.