Wayang kulit

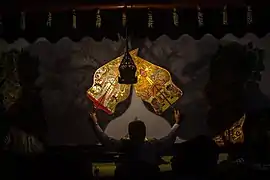

Wayang kulit is a traditional form of puppet-shadow play originally found in the cultures of Java, Bali, and Lombok in Indonesia.[1] In a wayang kulit performance, the puppet figures are rear-projected on a taut linen screen with a coconut-oil (or electric) light. The dalang (shadow artist) manipulates carved leather figures between the lamp and the screen to bring the shadows to life. It's mainly about good vs evil.

| Wayang Puppet Theatre | |

|---|---|

The Wayang Kulit performance by an Indonesian famous "dalang" (puppet master) Ki Manteb Sudharsono with the story "Gathutkaca Winisuda", in Bentara Budaya Jakarta, Indonesia, on 31 July 2010 | |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Criteria | Performing arts, Traditional craftsmanship |

| Reference | 063 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2008 (3rd session) |

| List | Representative List |

Wayang Kulit, Wayang Golek, Wayang Klithik | |

| Wayang Kulit | |

|---|---|

Wayang Kulit performance with Dalang | |

| Types | Indonesian wayang form |

| Ancestor arts | Javanese people |

| Originating culture | Indonesia |

| Originating era | Hindu - Buddhist civilisations |

Wayang kulit is one of the many different forms of wayang theatre found in Indonesia; the others include wayang beber, wayang klitik, wayang golek, wayang topeng, and wayang wong. Wayang kulit is among the best known, offering a unique combination of ritual, lesson and entertainment.

On November 7, 2003, UNESCO designated wayang puppet theatre, which is the flat leather shadow puppet (wayang kulit) and the three-dimensional wooden puppet (wayang golek or wayang klithik) theatre from Indonesia as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[2]

Etymology

The term wayang is the Javanese word for "shadow"[3] or "imagination". Its equivalent in Indonesian is bayang. In modern daily Javanese and Indonesian vocabulary, wayang can refer to the puppet itself or the whole puppet theatre performance. Kulit means "skin" or "leather", the material from which the figures are carved.

History

Hinduism arrived in Indonesia from India before the Islamic and Christian era. Sanskrit became the literary and court language of Java and later of Bali. Wayang kulit was later assimilated into local culture with changes to the appearance of the characters to resemble cultural norms.

When Islam began spreading in Indonesia, the display of God or gods in human form was prohibited, and thus this style of shadow play was suppressed. King Raden Patah of Demak, Java, wanted to see the wayang in its traditional form, but failed to obtain permission from Muslim religious leaders.

Religious leaders attempted to skirt the Muslim prohibition by converting the wayang golek into wayang purwa made from leather and displayed only the shadow instead of the puppets themselves.[4]

Wayang puppet figures

The wayang comes in sizes from 25 cm to 75 cm. The important characters are usually represented by several puppets each. The wayang is usually made out of water buffalo hide and goat hide and mounted on bamboo sticks. However, the best wayang is typically made from young female buffalo parchment, cured for up to ten years. The carving and punching of the rawhide, which is most responsible for the character's image and the shadows that are cast, are guided by this sketch. A mallet is used to tap special tools, called tatah, to punch the holes through the rawhide. Making the wayang sticks from horn is a complicated process of sawing, heating, hand-molding, and sanding until the desired effect is achieved. When the materials are ready, the artist attaches the handle by precisely molding the ends of the horn around the individual wayang figure and securing it with thread. A large character may take months to produce.

There are important differences between the three islands where wayang kulit is played (due to local religious canon): [5] [6]

- In Java (where Islam is predominant), the puppets (named ringgit) are elongated, the play lasts all night and the lamp (named blencong) is, nowadays, almost always electric. A full gamelan with (pe)sinden is typically used.[7]

- In Bali (where Hinduism is predominant), the puppets look more real, the play lasts a few hours and, if at night, the lamp uses coconut oil. Music is mainly by the four gender wayang, with drums only if the story is from the Ramayana. There are no sinden. The dalang does the singing. Balinese dalangs are often also priests (amangku dalang). As such, they may also perform during daylight, for religious purposes (exorcism), without lamp and without screen (wayang sakral, or "lemah")[8]

- In Lombok (where Islam is predominant and Bali's influence is strong), vernacular wayang kulit is known as wayang sasak, with puppets similar to Javanese ringgits, a small orchestra with no sinden, but flutes, metallophones and drums. The repertoire is unique to the island and is based on the Muslim Menak Cycle (the adventures of Amir Hamzah).

- Some Javanese Wayang Kulit Figures

- Some Balinese Wayang Kulit Figures

- Some Sasak Wayang Kulit Figures

Performance

The stage of a wayang performance includes several components. A stretched linen canvas (kelir) acts as a canvas, dividing the dalang (puppeteer) and the spectator. A coconut-oil lamp (Javanese blencong or Balinese damar) – which in modern times is usually replaced with electric light – casts shadows onto the screen. A banana trunk (Javanese gedebog, Balinese gedebong) lies on the ground between the screen and the dalang, where the figures are stuck to hold them in place. To the right of the dalang sits the puppet chest, which the dalang uses as a drum during the performance, hitting it with a wooden mallet. In a Javanese wayang kulit performance, the dalang may use a cymbal-like percussion instrument at his feet to cue the musicians. The musicians sit behind the dalang in a gamelan orchestra setting. The gamelan orchestra is an integral part of the Javanese wayang kulit performance. The performance is accompanied by female singers (pesinden) and male singers (wirasuara).

The setting of the banana trunk on the ground and canvas in the air symbolizes the earth and the sky; the whole composition symbolizes the entire cosmos. When the dalang animates the puppet figures and moves them across the screen, divine forces are understood to be acting in his hands with which he directs the happening. The lamp is a symbol of the sun as well as the eye of the dalang.[9]

A traditional wayang kulit performance begins after dark. The first of the three phases, in which the characters are introduced and the conflict is launched, lasts until midnight. The battles and intrigues of the second phase last about three hours. The third phase of reconciliation and friendship is finished at dawn.[10]

Wayang shadow plays are usually tales from the two major Hindu epics, the Ramayana and Mahabharata. The puppet master contextualizes stories from the plays, making them relevant to current community, national or global issues. Gamelan players respond to the direction of the dalang.

- Gallery of Wayang Kulit

Painting the Wayang Kulit in a Jogyakarta factory

Painting the Wayang Kulit in a Jogyakarta factory Carving the leather in a Jogyakarta factory

Carving the leather in a Jogyakarta factory In the specialized village of Sukawati, Bali

In the specialized village of Sukawati, Bali All stages of the making of a Wayang Kulit

All stages of the making of a Wayang Kulit Central Javanese Wayang Kulit

Central Javanese Wayang Kulit Balinese Wayang Kulit

Balinese Wayang Kulit

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wayang kulit. |

References

- Ness, Edward C. Van; Prawirohardjo, Shita (1980). Javanese Wayang Kulit: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195804140.

- "Wayang puppet theatre - intangible heritage - Culture Sector - UNESCO". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- Mair, Victor H. Painting and Performance: Picture Recitation and Its Indian Genesis. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988. p. 58.

- Inna Solomonik. "Wayang Purwa Puppets: The Language of the Silhouette". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 136 (1980), no: 4, Leiden, pp. 482-497.

- Claire Holt. Art in Indonesia, Continuities and Changes. Cornell University Press.

- Guenter Spitzing. Das Indonesische Schattenspiel. Dumont Taschenbuecher.

- James R. Brandon. On Thrones of Gold, Javanese Shadow Plays. Harvard University Press.

- Religion in Bali, by C. Hooykaas, University of Leiden

- Kathy Foley: "My Bodies: The Performer in West Java". TDR, Vol. 34, No. 2, Summer 1990, pp. 62–80, here p. 75f.

- Constantine Korsovitis: "Ways of the Wayang". India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 2 ("The Everyday, the Familiar and the Bizarre") Summer 2001, pp. 59–68, here p. 60.

External links

- "Bali & Beyond Educational Resources". www.balibeyond.com. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- "Wayang Kulit - a shadow play". minyos.its.rmit.edu.au. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- Shadow Music of Java, CD with thirteen-page booklet. Rounder CD 5060.