West Jerusalem

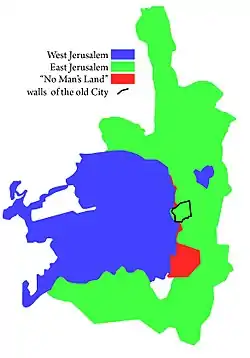

West Jerusalem or Western Jerusalem refers to the section of Jerusalem that remained under Israeli control after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, whose ceasefire lines delimited the boundary with the rest of the city, which was then under Jordanian control.[1] A number of western countries such as the United Kingdom acknowledge de facto Israeli authority, but withhold de jure recognition.[2][3] Israel's claim of sovereignty over West Jerusalem is more widely accepted than its claim over East Jerusalem.[4]

History

War of 1948

Prior to the 1948 Palestine war, the area of West Jerusalem held one of the wealthiest Arab communities, numbering some 28,000 people, in the region. By the end of hostilities, only approximately 750 non-Jews remained in the area's Arab sector, mostly Greeks in the “Greek colony” neighborhood.[5] Following the war, Jerusalem was divided into two parts: the western portion, from which it is estimated roughly 30,000 Arabs had fled or been evicted, came under Israeli rule, while East Jerusalem came under Jordanian rule[1][6] and was populated mainly by Palestinian Muslims and Christians. The Jordanians expelled a Jewish community of some 1,500 from the Old City.[7]

After widespread looting, Israeli institutions managed to gather in around 30,000 books, mostly in Arabic, dealing with Islamic law, Qur’anic exegesis and translations of European literature, together with thousands of works from the holdings of churches and schools. Many were taken from the homes of Palestinian writers and scholars in Qatamon, Bak'a and Musrara.[8]

Division in 1949

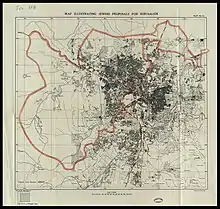

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine planned a “corpus separatum” for Jerusalem and its environs as an international city.[9]

Arabs living in such western Jerusalem neighbourhoods as Katamon or Malha were forced to leave; the same fate befell Jews in the eastern areas, including the Old City of Jerusalem and Silwan. Almost 33% of the land in West Jerusalem in the pre-mandate period had been owned by Palestinians, a fact which made it hard for the evicted Palestinians to accept Israeli control in the West. The Knesset (Israeli Parliament) passed laws to transfer this Arab land to Israeli Jewish organizations.[2]

The only eastern area of the city that remained in Israeli hands throughout the 19 years of Jordanian rule was Mount Scopus, where the Hebrew University of Jerusalem is located, which formed an enclave during that period and therefore is not considered part of East Jerusalem.

Capital of Israel

Israel established West Jerusalem as its capital in 1950.[2] The Israeli government needed to invest heavily to create employment, building new government offices, a new university, the Great Synagogue and the Knesset building.[10] West Jerusalem became covered by the Law and Administrative Ordinance of 1948, subjecting West Jerusalem to Israeli jurisdiction. United States President Donald Trump's administration announced recognition of Jerusalem as Israel's capital on December 6, 2017.[11] On December 15, 2018, Australia officially recognized West Jerusalem as Israel's capital.[12]

Reunification

During the Six-Day War in June 1967, Israel captured the eastern side of the city[13] and the whole West Bank. Over the following years, their control remained tenuous, the international community refusing to recognise their authority and the Israelis themselves not feeling secure.[13]

In 1980, the Israeli government annexed East Jerusalem and reunified the city but the international community disputed this.[1] The population of Jerusalem has largely remained segregated along the city's historical east/west division.[14] The larger city contains two populations that are "almost completely economically and politically segregated... each interacting with its separate central business district", supporting analysis that the city has retained a duocentric, as opposed to the traditional monocentric, structure.[14]

Mayors of West Jerusalem

- Dov Yosef (military governor) (1948–1949)[15]

- Daniel Auster (1949–1950)[16][17]

- Zalman Shragai (1951–1952)[17][18]

- Yitzhak Kariv (1952–1955)[17][19]

- Gershon Agron (1955–1959)[17][20]

- Mordechai Ish-Shalom (1959–1965)[17][21]

- Teddy Kollek (1965–1993)[17][22]

- Ehud Olmert (1993–2003)[17][23]

- Uri Lupolianski (2003–2008)[17][24]

- Nir Barkat (2008–2018)[25]

- Moshe Lion (2018–present)[26]

See also

Notes

Citations

- "Key Maps". Jerusalem: Before 1967 and now. BBC News. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- Dumper 1997, pp. 35–36.

- Moshe Hirsch; Deborah Housen-Couriel; Ruth Lapidot (28 June 1995). Whither Jerusalem?: Proposals and Positions Concerning the Future of Jerusalem. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 978-90-411-0077-1.

What, then, is Israel's status in west Jerusalem? Two main answers have been adduced: (a) Israel has sovereignty in this area; and (b) sovereignty lies with the Palestinian people or is suspended.

- Bisharat, George (23 December 2010). "Maximizing Rights". In Susan M. Akram; Michael Dumper; Michael Lynk (eds.). International Law and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: A Rights-Based Approach to Middle East Peace. Routledge. p. 311. ISBN 978-1-136-85098-1.

As we have noted previously the international legal status of Jerusalem is contested and Israel’s designation of it as its capital has not been recognized by the international community. However its claims of sovereign rights to the city are stronger with respect to West Jerusalem than with respect to East Jerusalem.

- Amit 2011.

- Dumper 1997, pp. 30-31.

- Tessler, Mark A. (1994). A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-253-20873-6.

- Amit 2011, pp. 7, 9.

- Greenway, H.D.S. (23 July 1980). "Explainer; The 3000 years of battling over Jerusalem". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- Dumper 1997, pp. 20–21.

- Landler, Mark (6 December 2017). "Trump Recognizes Jerusalem as Israel's Capital and Orders U.S. Embassy to Move". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- "Australia recognizes west Jerusalem as the capital of Israel". CBS News. 15 December 2018.

- Dumper 1997, p. 22.

- Alperovich, Gershon; Joseph Deutsch (April 1996). "Urban structure with two coexisting and almost completely segregated populations: The case of East and West Jerusalem". Regional Science and Urban Economics. 26 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1016/0166-0462(95)02124-8.

- Archive of Jerusalem's 1949 wartime governor for sale in U.S, Haaretz

- Summary record of a meeting between the committee on Jerusalem and Mr. Daniel Auster, Mayor of Jerusalem (Jewish sector)

- "Former Mayors of Jerusalem 1948–2008". City of Jerusalem website. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- "Shlomo Zalman Shragai, 96, a former mayor of Jerusalem and..." Baltimore Sun. 4 September 1995. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- Eisenberg, Ronald L. (2006). The Streets of Jerusalem: Who, What, Why. Devora Publishing Company. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-932687-54-5.

- "Biography: Gershon Agron". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- "Mordechai Ish-Shalom, Jerusalem Ex-Mayor, 90". New York Times. 23 February 1991. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- Wilson, Scott (2 January 2007). "Longtime Mayor of Jerusalem Dies at 95". The Washington Post. p. 2. Retrieved 2007-01-02.

- Senyor, Eli (15 April 2010). "Olmert cited as 'senior official' in Holyland affair". Ynetnews.com. Retrieved 2012-02-14.

- Erlanger, Steven (16 July 2005). "An Ultra-Orthodox Mayor in an Unorthodox City". The New York Times.

- "Secularist 'wins Jerusalem vote'". BBC News. 11 November 2008.

- Schneider, Tal (14 November 2018). "Moshe Lion elected Jerusalem Mayor in dramatic finish". Globes. Retrieved 2021-01-24.

Sources

- Amit, Gish (Summer 2011). "Salvage or Plunder? Israel's "Collection" of Private Palestinian Libraries in West Jerusalem". Journal of Palestine Studies. 40 (4): 6–23. doi:10.1525/jps.2011.xl.4.6. JSTOR 10.1525/jps.2011.xl.4.6.

- Dumper, Michael (1997). The politics of Jerusalem since 1967. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10640-5.

- Krystall, Nathan (1998). "The De-Arabization of West Jerusalem 1947-50". Journal of Palestine Studies. 27 (2): 5–22. JSTOR 2538281.

External links

West Jerusalem travel guide from Wikivoyage

West Jerusalem travel guide from Wikivoyage