West New Guinea dispute

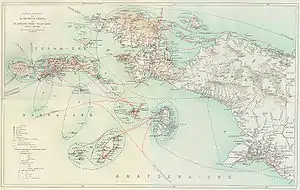

The West Irian Dispute (1950–1962), also known as the West New Guinea Dispute, was a diplomatic and political conflict between the Netherlands and Indonesia over the territory of Netherlands New Guinea. When the Netherlands had ceded sovereignty to Indonesia on 27 December 1949 following an Indonesian National Revolution, the Netherlands had rejected the claim that the Dutch-controlled half of New Guinea on the basis that it had belonged to the Dutch East Indies and that the new Republic of Indonesia was the legitimate successor to the former Dutch colony.

After a long struggle, West Irian was officially integrated into Indonesia based on the results of the Act of Free Choice (PEPERA) on 1969.

Historical background

Before the Dutch arrival, two Indonesian sultanates known as Sultanate of Tidore and Sultanate of Ternate ware claimed to have taken control of West Papua. Under the 1660 agreement between the Sultanate of Tidore and the Sultanate of Ternate, which was under Dutch colony, Papuans were recognized as subjects of the Sultanate of Tidore. Then under the 1872 treaty, the Sultanate of Tidore recognized Dutch control over its entire territory, which was used by the Kingdom of the Netherlands to establish West Papua as part of the official colony of the Dutch East Indies.

Less than a week after Indonesia's independence in 1945, the Dutch returned with allies and started a series of armed clashes in various places including Jakarta until in early 1946, the capital was moved to Yogyakarta.

On March 25, 1947, the Netherlands and Indonesia succeeded in mutually agreeing on the Linggarjati Agreement. However, on July 21, 1947, Lieutenant Governor General of the Netherlands Johannes van Mook confirmed that the results of the Linggarjati Negotiations were no longer valid and started a military operation known as the Dutch Military Aggression I which lasted until August 5, 1947.The Dutch named this military operation as the Police Action and declare this act as a domestic affair.

From 1947-1948, The Dutch used Devide et Impera politics or divisive politics which was a combination of political, military and economic strategies to gain and maintain power by dividing large groups into smaller groups that were easier to conquer. This policy of suppression was carried out by the Dutch with the establishment of puppet states in East Sumatra, Madura, Pasundan, South Sumatra and East Java in 1947-1948 to foster separatism.

On 22 December 1948, the Indonesian delegation discussed violations of the Linggarjati Negotiations, deployment of Dutch military operations, and the detention of high Indonesian government officials at the UN session in Paris. The Dutch delegation at the United Nations rejected Indonesia's claims by stating that conditions in Indonesia had returned to normal and the leaders who had been held were allowed to move freely. However, on January 15, 1949, two members of the Three Nations Commission (KTN) were sent into exile and did not find the truth in the Dutch claim.

The Indonesian delegation then attended the Inter-Asian Conference in New Delhi on January 20-23, 1949 which was attended by representatives of a number of countries and produced a forum agreement asking for UN assistance to solve problems between the Netherlands and Indonesia. During its mediation, the United Nations issued Resolution 67 dated January 28, 1949 which appealed to the Dutch to stop their military action in Indonesia and for Indonesia to stop fighting against the Dutch. After that the military aggression was stopped, but the Dutch rejected most of the contents of the resolution and carried out the General Offensive on 1 March 1949.

In an effort to end the Dutch-Indonesian conflict, The Hague agreement or the Round Table Conference Agreement (KMB) was ratified on November 2, 1949. This agreement stated that the Netherlands agreed to transfer their political sovereignty over the entire territory of the former Dutch East Indies with West Papua to become the only part of the Dutch East Indies that was not transferred to Indonesia and the status of West Papua will be discussed a year later, namely 1950. To help defend the Papuan colony from the infiltration of Indonesian troops, the Papoea Vrijwilligers Korps (PVK) force consisting of indigenous Papuans was formed by the Dutch in 1961.

The Netherlands continued the formation of a committee on 19 October 1961 which drafted the Manifesto for Independence and Self-Government, the national flag (the Morning Star Flag), the national stamp, chose "Hai Tanahku Papua" as the national anthem, and asked people to be recognized as Papuans. The Netherlands recognized this flag and song on 18 November 1961, and these regulations came into force on 1 December 1961.

The steps taken by the Netherlands was a violation of the KMB agreement. Subsequently, the Dutch carried out the attack on Yogyakarta on 19 December 1949 which marked the beginning of the Dutch Military Aggression II. Until 19 December 1961, Indonesian President Soekarno announced that he would carry out Operation Trikora.

Trikora Operation

December 1, 1961, the Papuan flag was raised in Jayapura. Then, 18 days after that President Soekarno in Yogyakarta triggered the tri komando rakyat (TRIKORA) which, among other things, contained an order to cancel the puppet state of Papua made in the Netherlands. Operation Trikora, announced on December 19, 1961, was aimed at planning, preparing and carrying out military operations to unify West Papua (then called West Irian) with Indonesia.

Basically, Trikora is the liberation of all the former Dutch colonies from Sabang to Merauke. In other words, Operation Trikora was launched to free Papua from the grip of Dutch imperialism. Efforts to restore Papua into Indonesia lap was also championed by one of the Papuan heroes, Frans Kaisiepo.

Kaisiepo proposed to change the name Netherland Nieuw Guinea to Irian (Join the Republic of Indonesia Anti-Nederland). As a result, Frans Kaisiepo became a political prisoner from 1954 to 1961. Trikora's aim was not solely for territorial liberation, but also for the liberation of all Papuan people from colonialism, underdevelopment, poverty, ignorance and to place oneself in a quality and dignified social society strata.

Conflict in Papua

The Papuan conflict began to increase significantly in 2018. At that time, a terrible tragedy occurred on December 2, 2018 in which 19 workers of the Trans Papua road project were shot dead in the Nduga region by the Papuan armed separatists led by Egianus Kogoya.

According to history since Indonesia's independence in 1945, West Irian has become a political dispute area. This dispute lasted since the Round Table Conference (KMB) on December 27, 1949 until a dozen years later. Until an international forum initiated by the United States through a BUNKER PLAN agreement (The idea of a person named bunker - a former US Ambassador who imitated the plebiscite of the United States controlling Hawaii at the behest of John F.Kennedy-President of the United States), NEW YORK AGREEMENT ( 1962) signed by Dutch Indonesia to end the political dispute over West Irian.

The essence of the New York Agreement is that the Netherlands surrendered Papua under the control of the United Nations Provisional Executive Authority (UNTEA) on 1 October 1962. Furthermore, the Netherlands had to surrender western Papua to Indonesia no later than 1 May 1963. However, since the agreement was signed, there have been voices against it.

On July 14 to August 2, 1969, finally the Determination of Penentuan Pendapat Rakyat (Pepera) or Act of Free Choice was held as a referendum determining whether the Papuans wanted to join Indonesia or not. Pepera is a political agreement between Indonesia and the Netherlands, previously Indonesia inherited the former Dutch East Indies colony, from Sabang to Merauke.

The referendum was attended by 1,026 members of the Pepera Deliberative Council (DMP) representing 815,904 Papuans. DMP members consist of 400 tribal and customary heads, 360 people from regional elements, 266 people from elements of community organizations. DMP then chose Papua to remain part of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia. However, some Papuans felt that the results of the Pepera did not fully represent their wishes.

According to the Spokesperson for the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Teuku Faizasyah, the results of the 1969 Pepera were already very strong. The Pepera was held based on an agreement between Indonesia and the Netherlands and the United Nations, with agreed mechanisms and rules, including a representative system. The representative system is even still relevant to contemporary conditions, because the Papuan people have until now been familiar with the "noken" system - which allows representatives to cast ballots - in both national and regional elections. The results of the 1969 Pepera have been brought to and accepted by the UN General Assembly, and have become UN Resolution 2504.

The dissatisfaction of the Papuan population with the results of the 1969 Pepera has sparked more serious resistance by forming a military political movement often referred to as the Free Papua Movement (OPM). OPM armed resistance broke out for the first time on 26 July 1965 in Manokwari. Then, according to the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC) report entitled "The Current Status of The Papuan Pro-Independence Movement", Freeport's mining activities in 1973 triggered OPM military activity in Timika. Then in May 1977, about 200 OPM guerrillas attacked Freeport and responded with military operations. Since then, cases of violence and human rights violations have continued to occur in Papua.

Furthermore, a wave of violence that occurred around the end of 2019 resulted in 8 civilians being killed in Deiyai during the riots on August 28, 2019. Then, another riot occurred on September 26, 2019 which resulted in 33 people being killed in Wamena and 4 people dying in Jayapura.

Movements carried out by separatist groups are often sporadic and poorly coordinated. In recent years, the Papuan independence movement has also grown and penetrated into international campaigns as a bridge/media for carrying out their actions. This is because the armed movement is no longer considered effective in realizing the desired vision. As a result, they are the masterminds of all conflicts in Papua.

Therefore, separatists carry out an active international campaign and raise sensitive issues about Papua to the United Nations (UN), as well as to various countries. Despite frequent attempts, there is no single country in the world that recognizes Papua as a country.

Further reading

- Anderson, Benedict (1983; 2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - Catley, Bob; Dugis, Vinsensio (1998). Australian Indonesian Relations Since 1945: The Garuda and The Kangaroo. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

- Crocombe, Ron (2007). Asia in the Pacific Islands. Suva, Fiji: IPS Publications, University of the South Pacific.

- Djiwandono, Soedjati (1996). Konfrontasi Revisited: Indonesia's Foreign Policy Under Soekarno. Jakarta: Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

- Green, Michael (2005). "Chapter 6: Uneasy Partners: New Zealand and Indonesia". In Smith, Anthony (ed.). Southeast Asia and New Zealand: A History of Regional and Bilateral Relations. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington. pp. 145–208. ISBN 0-86473-519-7.

- Ide Anak Agung Gde Agung (1973). Twenty Years Indonesian foreign policy, 1945-1965. The Hague: Mouton.

- Kahin, Audrey; Kahin, George McTurnan (1995). Subversion as Foreign Policy: The Secret Eisenhower and Dulles Debacle in Indonesia. New York: The New Press.

- Legge, John D. (2003). Sukarno: A Political Biography. Singapore: Archipelago Press, Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 981 4068 64 0.

- Lijphart, Arend (1966). The Trauma of Decolonization: The Dutch and West New Guinea. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Mackie, Jamie (2005). Bandung 1955: Non-Alignment and Afro-Asian Solidarity. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

- Muraviev, Alexey; Brown, Colin (Desember 2008). "Strategic Realignment or Déjà vu? Russia-Indonesia Defence Cooperation in the Twenty-First Century". SCDC Working Papers. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Canberra (411): 42. Retrieved 26 Mei 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=and|date=(help) - "Operation Trikora - Indonesia's Takeover of West New Guinea". Pathfinder: Air Power Development Centre Bulletin. Air Power Development Centre (150): 1–2. Februari 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2013. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Platje, Wies (2001). "Dutch Sigint and the Conflict with Indonesia 1950-62". Intelligence and National Security. 16 (1): 285–312. doi:10.1080/714002840. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- Singh, Bilveer (2001). "West Irian and the Suharto Presidency: a perspective". The Act of Free Choice: 73–93. Retrieved 26 Meo 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help)