William B. Jordan

William Bryan "Bill" Jordan Jr.[1][2] (May 8, 1940 – January 22, 2018) was an American art historian and one of the foremost experts on Spanish paintings. His work was focused primarily on bodegóns—a still life depicting pantry items—and paintings from the first half of the 17th century, especially by Juan van der Hamen. He organized exhibitions and catalogs at museums and art institutes worldwide. His research and books expanded upon the knowledge of the works and lives of many artists. Jordan worked as an art expert and helped individuals and institutions to acquire various paintings.

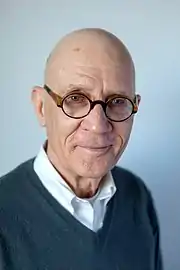

William B. Jordan | |

|---|---|

Jordan around 2011–13 | |

| Born | May 8, 1940 Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | January 22, 2018 (aged 77) Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Washington & Lee University (BA) New York University Institute of Fine Arts (MA, PhD) |

| Occupation | Art historian |

| Known for | Spanish art research, curation, acquisitions, collection |

Jordan became the founding director of the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University the year he completed his doctorate and is credited with turning its collection into the most prominent collection of Spanish art outside Spain. He later became the chair of fine arts at the Meadows School of the Arts, and then the deputy director of the Kimbell Art Museum. Jordan was on the board of various art institutes and museums, and an honorary trustee of the Prado Museum. He maintained a private collection with his husband, from which they donated a number of works to several institutes.

Early life

.jpg.webp)

William B. Jordan was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on May 8, 1940. He had three sisters, Ettie Lu Jordan Soard, Frances Jordan Hearn-Rigney and Sue Jordan Rodarte.[3] He spent his childhood in San Antonio, Texas, and attended Alamo Heights High School.[4] During summers he worked at the McNay Art Museum, where his mentor was its first director John Palmer Leeper; his work there led to his interest in art. He completed his bachelor's degree at the Washington & Lee University. He received his master's and doctorate in the history of Spanish art from the New York University Institute of Fine Arts, in 1964 and 1967.[4][1] His collaborations with his teacher José López-Rey sparked his interest in Spanish art history and he began researching Juan van der Hamen in the early 1960s.[5][6]

In his two-volume dissertation Juan van der Hamen y León, a Madrillenian Still-Life Painter from 1967, he presented an early monograph on the painter.[6] In this publication, he expanded upon the knowledge of van der Hamen at the time and described his "three-stage composition type" for the first time.[7] For his thesis he evaluated archival sources, which enabled him to write the first comprehensive biography of van der Hamen. Later, Jordan stayed in Spain several times to publish another and more extensive monograph on van der Hamen. However, this project was not completed. He curated several exhibitions about van der Hamen and was able to update information about van der Hamen in the associated publications instead.[8]

Career

Meadows Museum and Southern Methodist University: 1967–1981

.jpg.webp)

When the Meadows Museum opened at the Southern Methodist University in Dallas, it was struggling with an art scandal that had damaged its reputation; forty-four paintings in the museum's collection turned out to have been forgeries, including a dozen works by Elmyr de Hory.[9][10] In 1966, while still a doctoral student, Algur H. Meadows, the museum's founder and benefactor, offered Jordan the position as its director. He visited the museum with López-Rey and they assessed the works and determined that many of the older paintings in the collection were falsely attributed.[5][1] Jordan commented that the collection "was not very good" and that he would have to "essentially build from scratch".[11] He agreed to accept the position if Meadows would make changes to the collection; Meadows put aside US$1 million to fund them, and Jordan took the job.[1]

In 1967, Jordan became the founding director and chairman of the division of fine arts of the Meadows Museum. Meadows appointed him to the position even though he had no prior work experience, within the year Jordan had completed his doctorate.[2][4][12] The museum closed for a few months, and Jordan began evaluating its collection with help from López-Rey and Diego Angulo Íñiguez.[5] He auctioned off paintings he deemed insignificant for a museum collection and put others in reserve for study purposes. The thirty-five auctioned paintings brought in only US$35,000. Jordan revamped the collection by acquiring new paintings before the museum reopened; the collection included works by Francisco Goya, Francisco de Zurbarán, and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo.[10]

.jpg.webp)

Jordan split his time teaching and collecting. He taught courses on the history of Spanish art and on museums and collecting at the Southern Methodist University.[10] While they initially purchased paintings together, Meadows eventually trusted Jordan and acquired paintings without seeing them if Jordan had vetted them.[10] In 1976, Jordan was given the additional post of adjunct curator of European art at the Dallas Museum of Art and the chair of fine arts at the Meadows School of the Arts.[2][13]

Throughout his term, Jordan continued to acquire a number of prominent works at auctions and from art dealers with Meadows' financial support, and expanded the collection significantly.[10][2] He acquired around 75 works during his tenure, which included important paintings by Murillo, Diego Velázquez, Jusepe de Ribera, and de Zurbarán. The collection included six significant works of Goya from the 18th and 19th centuries, and notable 20th-century paintings by Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and Juan Gris.[10] He helped to develop the museum's modern sculpture collection", with works by Auguste Rodin, Alberto Giacometti, Henry Moore, and Aristide Maillol.[13] Jordan is credited for turning the Meadows Museum's collection into the most prominent collection of Spanish art outside Spain.[13][4]

Kimbell Art Museum: 1981–1990

Jordan left the Meadows Museum to serve as the deputy director, chairman of the scholars' committee and chief curator of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, in 1981.[14][4] He joined after his former colleague and director of the museum, Ted Pillsbury, offered him the position.[2] Pillsbury and Jordan worked together to acquire paintings and created an exhibitions program at the museum.[2][15]

As the chairman of the scholars' committee, he helped to organize the El Greco of Toledo exhibition in 1982. The exhibition was being planned since 1978 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the painter's move to Toledo, Spain.[16] The exhibition was called "historic" and contained the most extensive collection of paintings by El Greco; it included 66 paintings, 32 of which were from Spain, and the rest from museums across the U.S.[4][16] The National Gallery of Art, the Toledo Museum of Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Prado Museum each hosted the exhibition. John Russell writing for The New York Times said that "the exhibition fulfills, in fact, a dream that has haunted the human imagination for more than 100 years".[17]

In 1985, he curated the museum's Spanish Style Life in the Golden Age 1600–1650 exhibition. It focused on works of de Zurbarán, Juan Sánchez Cotán, and van der Hamen. He wrote descriptive labels for the museum's paintings and descriptions for the works in In Pursuit of Quality, a 1987 book published by the museum.[6] Jordan was provided with a bigger budget at the museum which he used for exhibitions and acquiring prominent paintings such as Portrait of Don Pedro de Barberana y Aparregui (1631–1633) by Velázquez and Four Figures on a Step (1655–1660) by Murillo.[4][6] He is credited with making its collection "considerably more meaningful to the public".[4]

Retirement and independent work: 1990–2018

Jordan left the Kimbell Art Museum and retired at age 50 in 1990—following in the footsteps of his father, who had retired at 49.[11] He worked as an independent art consultant and became a board member of institutes such as The Foundation for the Arts, Dallas Museum of Art, and Meadows School of the Arts.[2][4] Different institutions, including those he had been affiliated with in the past, continued to seek his advice on acquisitions and exhibition; he continued to work with them at his discretion.[2] He also published books and helped to organize exhibitions worldwide. He was involved in producing the catalog for Spanish Still Life from Velázquez to Goya at the National Gallery, London, in 1995. It was published the same year as an eponymous book.[6] In 1997, he published An Eye on Nature: Spanish Still-Life Paintings from Sánchez Cotán to Goya, a book analyzing still life paintings and artists.[18]

In 2001, he joined the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas as a member of the board of directors and played an active role in various projects.[2][19] He then served as the trustee of the center and the Nasher Foundation.[20] In 2005 and 2006, Jordan curated the Juan Van Der Hamen Y León and the Court of Madrid which was on display in Madrid and Dallas. He showed van der Hamen's work as a history painter and portraitist on an equal footing with his bodegóns, and discussed some of the works he attributed to him. In 2005, he published an eponymous catalog on the occasion of this exhibition, focusing on new assessments and research on the artist of the 1620s.[6][7]

In 2010, he headed the search committee to find a new director of the Chinati Foundation—where he was a member of the board of directors and past president—which led to the appointment of Thomas Kellein.[4][21] He worked with Olivier Meslay at the Dallas Museum of Art to create an exhibition and a catalog of modern European paintings in local private collections in 2013.[2] They published their work in Mind's Eye: Masterworks on Paper from David to Cézanne the following year.[22] In 2017, he was appointed an honorary trustee of the Prado Museum.[3] Jordan died on January 22, 2018, at the William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital from complications of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and was buried at the Hillcrest Mausoleum & Memorial Park in Dallas.[4][23]

Art acquisitions and philanthropy

Jordan was frequently called upon as an art expert; he made a name for himself for being able to tell reproduced copies from authentic paintings. He also maintained an art collection with his husband Robert Dean Brownlee at their residence in Turtle Creek, Dallas.[4][2] Sam Holland, the dean of the Meadows School of the Arts, commented on Jordan's abilities: "He had a brilliant gift for art. There's something that's hard to quantify that sets somebody apart from the rest of us — his ability to spot authenticity on the highest level of the art world."[4] He was considered to have an "eye" for significant paintings that were unattributed at the time and acquiring them at auctions for relatively little money.[2]

There's a lot wrong about art now. I mean so much of the art today is silly. It's hard to find art of very great quality today. But it does exist.

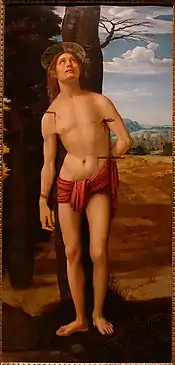

In 1976, Jordan noticed San Sebastián (1506) by Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina in Manuel González's gallery in Madrid. The painting was not attributed to Yáñez, and there were no records in Spanish sources to prove it was his work. However, Jordan was confident, and he made the purchase with Meadows' support. Research confirmed that the painting was indeed a work by Yáñez, and it was "universally regarded as one of the artist's masterpieces"; it became one of the more important works in the Meadows collection.[10]

He helped acquire Fox in the Snow (1860) by Gustave Courbet in 1979 for the Dallas Museum of Art, a painting that was outside his area of expertise.[4] In 1990, he was called as an expert by the San Diego Museum of Art during their acquisition of The Adoration of the Shepherds (1572–74) by El Greco and St. Sebastian (1604) by Juan Sánchez Cotán. He had noticed St. Sebastian at an auction in New York, where it was bought by a local dealer. The painting was vaguely attributed to a "Flemish master" during the auction, but he recognized that it was a work by Cotán. The museum purchased the work after the painting was vetted and its attribution confirmed by Jordan.[24]

Jordan's most notable acquisition was of Portrait of Philip III (1623–1631) by Diego Velázquez in 1988.[4][2] He found the piece at a London auction, where it was titled Portrait of a gentleman by Justus Sustermans. He acquired the painting for £1,000 and had it restored at the Kimbell Art Museum by Claire Barry. He believed it to be a painting by Velázquez, done in preparation of The Expulsion of the Moriscos (1627), which had won him a first prize and an appointment as gentleman usher to the king in the court of Philip IV; the painting is considered to have been burned in the Royal Alcázar of Madrid fire of 1734.[12][25]

Jordan found that historical descriptions of Philip III in The Expulsion of the Moriscos match the expressions and direction of Portrait of Philip III. He concluded that Velázquez's style—which is regarded to be incomparable to other portraitists of the time—was similar to his works of that period, and that the unusual depiction of Philip III looking up, instead of forward and straight, indicated that the painting was made to serve as a model to be included in a wider scene.[12] Jordan kept the painting in his private collection for almost 30 years.[14] In 2016, the Prado Museum used x-ray and infrared radiography to compare its construction and preparation to his other works of the period, and confirmed its authenticity. The painting was subsequently valued at around US$6 million.[26] Later that year, he donated it to a non-profit organization called the American Friends of Prado Museum, which then gave the painting to the museum as a long-term deposit.[12]

The Dallas Museum of Art established a Works on Paper Department with contributions from the William B. Jordan and Robert Dean Brownlee Endowment in 2019. Jordan and Brownlee also donated over 80 different works of art to the museum; fifty-eight of them were works on paper. Their donation included oil paintings and furniture from the 19th and 20th centuries and other antiquities such as silver works, ceramics, and sculptures.[27] In 2020, Brownlee donated works by John Chamberlain, David McManaway, Joan Miró, and Claes Oldenburg to the Nasher Sculpture Center on behalf of him.[20] A Baby Rolling Over (1884–87) by Agustí Querol Subirats was donated to the Meadows Museum by art historian Michael P. Mezzatesta in honor of William B. Jordan in 2020; Jordan had previously donated a sculpture of Saint John the Baptist by Luisa Roldán to the museum in 1999, which was similar in style.[28]

Bibliography

Author

- Juan van der Hamen y León, a Madrillenian Still-Life Painter (1967)

- Murillo's Jacob Laying the Peeled Rods Before the Flocks of Laban (1968)

- The Meadows Museum: A Visitor's Guide to the Collection (1974)

- Juan Van Der Hamen Y León (1980)

- Spanish Still Life in the Golden Age, 1600-1650 (1985)

- La imitación de la naturaleza: los bodegones de Sánchez Cotán (1992)

- Spanish Still Life from Velázquez to Goya (1995)

- An Eye on Nature: Spanish Still-life Paintings from Sanchez Cotan to Goya (1997)

- Juan van der Hamen, La aparición de la Inmaculada a San Francisco: Convento de Santa Isabel de los Reyes, Toledo (2004)

- Juan Van Der Hamen Y León & the Court of Madrid (2005)

- Donación de Plácido Arango Arias al Museo del Prado (2016)

Editor

- Jusepe de Ribera, Lo Spagnoletto, 1591-1652 (1982)

- A Prosperous Past: The Sumptuous Still Life in the Netherlands, 1600-1700 (1989)

- Mind's Eye: Masterworks on Paper from David to Cézanne (2014)

References

- McWhirter, William (July 7, 1967). "Art Swindle". Life. Vol. 63 no. 1. Time Inc. p. 58. ISSN 0024-3019.

- "Farewell to Bill Jordan". Edith O'Donnell Institute of Art History. February 1, 2018. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- "William Bryan Jordan". Obituaries. San Antonio Express-News. Hearst. February 4, 2018. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020 – via Legacy.com.

- Brettell, Rick; Simnacher, Joe (January 23, 2018). "William Jordan, art historian and philanthropist who enriched Dallas-Fort Worth museums, dies at 77". The Dallas Morning News. A. H. Belo. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- Curlee, Kendall. "Meadows Museum". Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Oppermann, Ira (2007). Das spanische Stillleben im 17. Jahrhundert. Vom fensterlosen Raum zur lichtdurchfluteten Landschaft (in German). Berlin: Reimer. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-496-01368-6.

- Jordan, William B., Jr. (2005). Juan Van Der Hamen Y León & the Court of Madrid. Yale University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-300-11318-1.

- Scheffler, Felix (2000). Das spanische Stilleben des 17. Jahrhunderts: Theorie, Genese und Entfaltung einer neuen Bildgattung (in German). Vervuert. p. 261. ISBN 978-3-89354-515-5.

- Wecker, Menachem (November 17, 2017). "Praying for Success: In the Wake of Scandal, Can the Museum of the Bible Find Mass Appeal?". Artnet. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- "Founding Director William B. Jordan, 1940-2018". Meadows Museum. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- Bothwell, Anne (January 26, 2018). "Remembering William Jordan, An Art Authority". Art&Seek. KERA. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- "The Museo del Prado is presenting an unpublished work by Velázquez donated to American Friends by William B. Jordan". Prado Museum. December 14, 2016. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- "SMU and the Meadows Community Mourn the Passing of an Icon". Southern Methodist University. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- Pulido, Natividad (December 19, 2016). "William B. Jordan: "No creo que haya mucho debate sobre la autoría del retrato de Felipe III de Velázquez"". ABC. Grupo Vocento. Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- Brock, Jessica (March 28, 2006). "Jordan's Spanish art knowledge brings elegance to exhibition". The Daily Campus. Southern Methodist University. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Markham, James M. (April 3, 1982). "El Greco exhibition opens in Madrid". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Russell, John (July 18, 1982). "Art view; seeing the art of El Greco as never before; Washington". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Jordan, William B., Jr. (1997). An Eye on Nature: Spanish Still-life Paintings from Sanchez Cotan to Goya (2, Illustrated ed.). Matthiesen Fine Art. ISBN 978-88-422-0758-0.

- "The Nasher Foundation Appoints Board". Nasher Sculpture Center. June 29, 2001. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- "Nasher Sculpture Center Announces Recent Acquisitions and Gifts to the Collection". Nasher Sculpture Center. February 10, 2020. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Thomson, Steven (August 24, 2010). "Westphalia meets West Texas: Marfa's Chinati Foundation selects German director". CultureMap Houston. Gow Media. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Meslay, Olivier; Jordan, William B., Jr., eds. (2014). Mind's Eye: Masterworks on Paper from David to Cézanne (Illustrated ed.). Dallas Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-300-20721-7.

- "William Jordan Obituary". Dignity Memorial. Service Corporation International. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- Freudenheim, Susan (November 30, 1990). "Museum Buys Early Painting by El Greco : Art: San Diego Museum of Art also acquires piece by 17th-Century Spanish still-life painter Juan Sanchez Cotan". Los Angeles Times. Nant Capital. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- Bailey, Anthony (November 8, 2011). Velázquez and The Surrender of Breda: The Making of a Masterpiece. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-4299-7377-9.

- Sullivan, Paul (August 11, 2017). "Even for Philanthropists, Museums Can Make Art a Tough Give". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- "Dallas Museum of Art Receives Transformative Gifts to Establish New Department and Curatorial Position Dedicated to Works on Paper". Dallas Museum of Art. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- "Spanish Art Acquisitions Enhance Meadows Museum Collection". Artfix Daily. Wildfire Media. August 20, 2020. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.