William Grant Still

William Grant Still Jr. (May 11, 1895 – December 3, 1978) was an American composer of nearly 200 works, including five symphonies, four ballets, eight operas, over thirty choral works, plus art songs, chamber music and works for solo instruments.

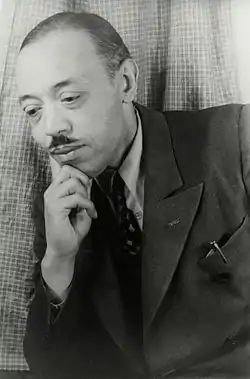

William Grant Still | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Still by Carl Van Vechten | |

| Born | May 11, 1895 Woodville, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | December 3, 1978 (aged 83) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

Often referred to as the "Dean of Afro-American Composers", Still was the first American composer to have an opera produced by the New York City Opera. Still is known primarily for his first symphony, Afro-American Symphony (1930), which was, until 1950, the most widely performed symphony composed by an American.

Born in Mississippi, he grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, attended Wilberforce University and Oberlin Conservatory of Music, and was a student of George Whitefield Chadwick and later Edgard Varèse.

Of note, Still was the first African American to conduct a major American symphony orchestra, the first to have a symphony (his 1st Symphony) performed by a leading orchestra, the first to have an opera performed by a major opera company, and the first to have an opera performed on national television.

Due to his close association and collaboration with prominent African-American literary and cultural figures, Still is considered to be part of the Harlem Renaissance movement.

Life

William Grant Still, Jr. was born on May 11, 1895, in Woodville, Mississippi.[1]:15 He was the son of two teachers, Carrie Lena Fambro[2] (1872–1927) and William Grant Still Sr[1]:5 (1871–1895). His father was a partner in a grocery store and performed as a local bandleader.[1]:5 William Grant Still Sr. died when his infant son was three months old.[1]:5

Still's mother moved with him to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she taught high school English.[1]:6 She met and in 1904[2] married Charles B. Shepperson, who nurtured his stepson William's musical interests by taking him to operettas and buying Red Seal recordings of classical music, which the boy greatly enjoyed.[1]:6 The two attended a number of performances by musicians on tour.[3] His maternal grandmother Anne Fambro[2] sang African-American spirituals to him.[4]:6, 12

Still started violin lessons in Little Rock at the age of 15. He taught himself to play the clarinet, saxophone, oboe, double bass, cello and viola, and showed a great interest in music. At 16 years old, he graduated from M. W. Gibbs High School in Little Rock.[4]:3

His mother wanted him to go to medical school, so Still pursued a Bachelor of Science degree program at Wilberforce University, a historically black college in Ohio.[5] Still became a member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. He conducted the university band, learned to play various instruments, and started to compose and to do orchestrations. He left Wilberforce without graduating.[1]:7

Upon receiving a small amount of money left to him by his father, he began studying at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.[6] Still worked for the school assisting the janitor, along with a few other small jobs outside of the school, yet still struggled financially.[6] When Professor Lehmann asked Still why he wasn't studying composition, Still told him honestly that he couldn't afford to, leading to George Andrews agreeing to teach him composition without charge.[6] He also studied privately with the modern French composer Edgard Varèse and the American composer George Whitefield Chadwick.[7]:249[2]

On October 4, 1915,[2] Still married Grace Bundy, whom he had met while they were both at Wilberforce.[1]:1,7 They had a son, William III, and three daughters, Gail, June, and Caroline.[2] They separated in 1932 and divorced February 6, 1939.[2] On February 8, 1939, he married pianist Verna Arvey, driving to Tijuana for the ceremony because interracial marriage was illegal in California.[1]:2[2] They had a daughter, Judith Anne, and a son, Duncan.[1]:2[2] Still's granddaughter is journalist Celeste Headlee by way of Judith Anne.

On December 1, 1976, his home was designated Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument #169. It is located at 1262 Victoria Avenue in Oxford Square, Los Angeles.[8]

Career

In 1916 Still worked in Memphis for W.C. Handy's band.[2] In 1918 Still joined the United States Navy to serve in World War I. After the war he went to Harlem, where he continued to work for Handy.[2] During his time in Harlem Still was involved with other important cultural figures of the Harlem Renaissance such as Langston Hughes, Alain Locke, Arna Bontemps, and Countee Cullen, and is considered to be part of that movement.[9]

He recorded with Fletcher Henderson's Dance Orchestra in 1921,[10]:85 and later played in the pit orchestra for Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake's musical, Shuffle Along[1]:4 and in other pit orchestras for Sophie Tucker, Artie Shaw, and Paul Whiteman.[11] With Henderson, he joined Henry Pace's Pace Phonograph Company (Black Swan).[12] Later in the 1920s, Still served as the arranger of Yamekraw, a "Negro Rhapsody" composed by the Harlem stride pianist James P. Johnson.[13]

In the 1930s Still worked as an arranger of popular music, writing for Willard Robison's Deep River Hour and Paul Whiteman's Old Gold Show, both popular NBC Radio broadcasts.[11]

Still's first major orchestral composition, Symphony No. 1 "Afro-American", was performed in 1931 by the Rochester Philharmonic, conducted by Howard Hanson.[2] It was the first time the complete score of a work by an African American was performed by a major orchestra.[2] By the end of World War II the piece had been performed in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Berlin, Paris, and London.[2] Until 1950 the symphony was the most popular of any composed by an American.[14] Still developed a close professional relationship with Hanson; many of Still's compositions were performed for the first time in Rochester.[2]

In 1934 Still moved to Los Angeles. He received his first Guggenheim Fellowship[15] and started work on the first of his eight operas, Blue Steel.[16]

In 1936, Still conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl; he was the first African American to conduct a major American orchestra in a performance of his own works.[17][11]

Still arranged music for films. These included Pennies from Heaven (the 1936 film starring Bing Crosby and Madge Evans) and Lost Horizon (the 1937 film starring Ronald Colman, Jane Wyatt and Sam Jaffe).[2] For Lost Horizon, he arranged the music of Dimitri Tiomkin. Still was also hired to arrange the music for the 1943 film Stormy Weather, but left the assignment because "Twentieth-Century Fox 'degraded colored people.'"[2]

Still composed Song of a City for the 1939 World's Fair in New York City.[18] The song played continuously during the fair by the exhibit "Democracity."[18] According to Still's granddaughter, he couldn't attend the fair except on "Negro Day" without police protection.[19]

In 1949 his opera Troubled Island, originally completed in 1939, about Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Haiti, was performed by the New York City Opera.[2] It was the first opera by an American to be performed by that company[20] and the first by an African American to be performed by a major company.[17] Still was upset by the negative reviews it received.[2]

In 1955 he conducted the New Orleans Philharmonic Orchestra; he was the first African American to conduct a major orchestra in the Deep South.[17] Still's works were performed internationally by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, and the BBC Orchestra.

In 1981 the opera A Bayou Legend was the first by an African-American composer to be performed on national television.[21]

Still was known as the "Dean of Afro-American Composers".[9][17] Still and Arvey's papers are held by the University of Arkansas.[9]

Legacy and honors

- Still received three Guggenheim Fellowships in music composition (1934, 1935, 1938)[15] and at least one Rosenwald Fellowship.[11]

- In 1949, he received a citation for Outstanding Service to American Music from the National Association for American Composers and Conductors[2]

- In 1976, his home in Los Angeles was designated a Historic-Cultural Monument.[8][22]

- He was awarded honorary doctorates[2] from Oberlin College, Wilberforce University, Howard University, Bates College, the University of Arkansas, Pepperdine University, the New England Conservatory of Music, the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, and the University of Southern California.

- He was posthumously awarded the 1982 Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters award for music composition for his opera A Bayou Legend.[2][23]:6

Selected compositions

Still composed almost 200 works, including eight operas,[24]:200 five symphonies,[24]:200 four ballets,[25] plus art songs, chamber music, and works for solo instruments.[2] He composed more than thirty choral works.[11] Many of his works are believed to be lost.[2]:278

- From the Land of Dreams (1924)[2][26]:4

- Darker America (1924)[7]:251

- From the Journal of a Wanderer (1925)[27]:224

- Levee Land (1925)[7]:251

- From The Black Belt (1926)[7]:252

- La Guiablesse (1927)[2]

- Sahdji (1930)[26]:4

- Africa (1930)[2]

- Symphony No. 1 "Afro-American" (1930, revised in 1969)[7]:253

- A Deserted Plantation (1933)[26]:4

- The Sorcerer (1933)[26]:4

- Dismal Swamp (1933)[7]:251

- Kaintuck (1933)[7]:252

- Blue Steel (1934)[26]:4

- Three Visions (1935)[7]:253

- Summerland (1935)[7]:253

- A Song A Dust (1936)[7]:253

- Symphony No. 2, "Song of A New Race" (1937)[7]:253[25]

- Lenox Avenue (1937)[7]:252

- Song of A City (1938)[7]:253

- Seven Traceries (1939)[26]:5

- And They Lynched Him on A Tree (1940)[7]:251

- Miss Sally's Party (1940)[26]:5

- Can'tcha line 'em, for orchestra (1940)[26]:5

- Old California (1941)[7]:252

- Troubled Island, opera, produced 1949 (1937–39)[2]

- A Bayou Legend, opera (1941)[2]

- Plain-Chant for America (1941)[7]:252

- Incantation and Dance (1941)[26]:5

- A Southern Interlude (1942)[26]:5

- In Memoriam: The Colored Soldiers Who Died for Democracy (1943)[7]:252

- Suite for Violin & Piano (1943)[26]:5

- Festival Overture (1944)[7]:251

- Poem for Orchestra (1944)[7]:252

- Bells (1944)[7]:251

- Symphony No. 5, "Western Hemisphere" (1945, revised 1970)[7]:253[25]

- From The Delta (1945)[7]:252

- Wailing Woman (1946)[26]:5

- Archaic Ritual Suite (1946)[7]:251

- Symphony No. 4, "Autochthonous" (1947)[7]:253

- Danzas de Panama (1948)[7]:251

- From A Lost Continent (1948)[7]:251

- Miniatures (1948)[7]:250

- Constaso (1950)[7]:251

- To You, America (1951)[7]:253

- Grief, originally titled as Weeping Angel (1953)

- The Little Song That Wanted To Be A Symphony (1954)[7]:252

- A Psalm for The Living (1954)[7]:252

- Rhapsody (1954)[7]:252

- The American Scene (1957)[7]:251

- Serenade (1957)[7]:252

- Ennanga (1958)[7]:251[26]:6

- Symphony No. 3, "The Sunday Symphony" (1958)[7]:253[28]

- Lyric Quartette (1960)[26]:7

- Patterns (1960)[7]:252

- The Peaceful Land (1960)[7]:252

- Preludes (1962)[7]:252

- Highway 1 USA (1963)[7]:252

- Folk Suite No. 4 (1963)[7]:251

- Threnody: In Memory of Jan Sibelius (1965)[7]:253

- Little Red School House (1967)[7]:252

- Little Folk Suite (1968)[7]:252

- Choreographic Prelude (1970)[7]:251

See also

- Black conductors

- List of African-American composers

- List of jazz-influenced classical compositions

- Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, an earlier Black British composer

References

- Still, Judith Anne; Dabrishus, Michael J.; Quin, Carolyn L. (1996). William Grant Still: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25255-6. OCLC 65339854.

- Whayne, Jeannie M. (2000). Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives. University of Arkansas Press. pp. 262, 276–278. ISBN 978-1-55728-587-4.

- Smith, Catherine Parson (2000). William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 307.

- Smith, Catherine Parsons (2008). William Grant Still. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03322-3.

- William Grant Still at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "William Grant Still". publishing.cdlib.org. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- Horne, Aaron (1996). Brass Music of Black Composers: A Bibliography. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29826-4.

- "Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) Report". Cityplanning.lacity.org. Department of City Planning, City of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Murchison, Gayle (1994). ""Dean of Afro-American Composers" or "Harlem Renaissance Man": "The New Negro" and the Musical Poetics of William Grant Still". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 53 (1): 42–74. doi:10.2307/40030871. ISSN 0004-1823. JSTOR 40030871.

- Gibbs, Craig Martin (2012). Black Recording Artists, 1877-1926: An Annotated Discography. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7238-3.

- Griggs-Janower, David (1995). "The Choral Works of William Grant Still". The Choral Journal. 35 (10): 41–44. ISSN 0009-5028. JSTOR 23550334.

- Smith, Jessie Carney (December 1, 2012). Black Firsts: 4,000 Ground-Breaking and Pioneering Historical Events. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1-57859-425-2.

- Staff (2021). "James P. Johnson". OxfordMusicOnline.com. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- Borroff, Edith, "Biographical Sketch of William Grant Still". Duke University Libraries.

- "William Grant Still". John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- Southern, Eileen, and William Grant Still. “William Grant Still.” The Black Perspective in Music, vol. 3, no. 2, 1975, pp. 172-173

- "William Grant Still, 1895–1978". The Library of Congress. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- "Music From The 1939 World's". NPR.org. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "A2Schools.org: PRI Co-Host Celeste Headlee, Conductor John McLaughlin Williams & Singer Daniel Washington in Ann Arbor Jan. 13". AfriClassical. January 16, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Shirley, Wayne, "Two Aspects of Troubled Island", American Music Research Center Journal, 2013.

- Oglesby, Meghann. "Black History Spotlight: William Grant Still". www.classicalmpr.org. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- "William Grant Still Residence". HistoricPlacesLA. Office of Historic Resources, Department of City Planning. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- Still, William Grant; Adams, Wellington (1937). Twelve Negro spirituals. Handy Brothers Music Co. OCLC 320893340.

- Kirk, Elise Kuhl (2001), American Opera, pp. 200–204. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252026233

- "William Grant Still, African American Composer, Arranger & Oboist". chevalierdesaintgeorges.homestead.com. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- Soll, Beverly (2005). I Dream a World: The Operas of William Grant Still. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-789-2.

- Smith, Catherine Parson (2000). William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 224.

- "STILL, W.S.: Symphonies Nos. 2, "Song of a New Race" and 3, "The Sunday Symphony" / Wood Notes (Fort Smith Symphony, Jeter) – 8.559676". www.naxos.com. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

Sources

- Horne, Aaron. Woodwind Music of Black Composers, Greenwood Press, 1990. ISBN 0-313272-65-4

- Roach, Hildred. Black American Music. Past and Present, second edition, Krieger Publishing Company 1992. ISBN 0-894647-66-0

- Sadie, Stanley; Hitchcock, H. Wiley. The New Grove Dictionary of American Music, Grove's Dictionaries of Music, 1986. ISBN 0-943818-36-2

Further reading

- Reef, Catherine (2003). William Grant Still: African American Composer. Morgan Reynolds. ISBN 1-931798-11-7

- Sewell, George A., and Margaret L. Dwight (1984). William Grant Still: America's Greatest Black Composer. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi

- Southern, Eileen (1984). William Grant Still – Trailblazer. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press.

- Still, Verna Arvey (1984). In One Lifetime. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press.

- Still, Judith Anne (2006). Just Tell the Story. The Master Player Library.

- Still, William Grant (2011). My Life My Words, a William Grant Still autobiography. The Master Player Library.

External links

- William Grant Still Music, Official Site

- Bibliography at Encyclopedia of Arkansas

- William Grant Still, A Study in Contradictions, University of California

- William Grant Still, Interview, African American Music Collection, University of Michigan

- William Grant Still, "Composer, Arranger, Conductor & Oboist". Extensive info at AfriClassical.com

- William Grant Still and Verna Arvey Papers, University of Arkansas, Special Collections Department, Manuscript Collection MC 1125