William Temple Franklin

William Temple Franklin, known as Temple Franklin, (22 February 1760, in London – 25 May 1823, in Paris) was an American diplomat and real estate speculator. He is best known for his involvement with the American diplomatic mission in France during the American Revolutionary War. Beginning at the age of 16, he served as secretary to his grandfather Benjamin Franklin, who negotiated and agreed to the Franco-American Alliance.

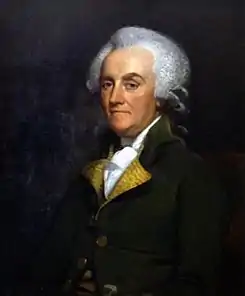

William Temple Franklin | |

|---|---|

William Temple Franklin, painted by John Trumbull (1790–91) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 22, 1760 Philadelphia, Province of Pennsylvania, British America |

| Died | May 25, 1823 (aged 63) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Spouse(s) | Hannah Collyer (m. 1823) |

| Children |

|

| Parents | William Franklin Mary Johnson D'Evelin (stepmother) |

| Occupation | Diplomat, real estate speculator, editor |

The younger Franklin was also secretary for the American delegation that negotiated United States independence at the Treaty of Paris in 1783. He returned to Philadelphia with his grandfather afterward. Finding his prospects limited in the United States, he later returned to Europe, where he lived mostly in France.

Early life and education

William Temple Franklin, called Temple, was born in 1760,[1] the illegitimate (and only) son of William Franklin, notably illegitimate as well, who sired him while a law student in London. His mother is unknown, and the infant was placed in foster care. His father William was the illegitimate but acknowledged son of Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, and raised in his household. William Temple Franklin's middle name is said to have been derived from his having been conceived while his father was studying at the Middle Temple.[2]

Later in 1762, William married "respectably",[1] to Elizabeth Downes in London, the daughter of a wealthy Barbados planter.[3] After passing the bar, he returned to North America, but he continued to pay for the upkeep and later education of Temple.[1]

In 1763, with the aid of his father Benjamin Franklin, William Franklin was appointed as the last colonial governor of New Jersey and went to North America. He left Temple in foster care. William's position as a Loyalist later put him at odds with his father, and they broke permanently over it. William Franklin was imprisoned during the Revolution and afterward forced into exile in Britain.

Benjamin Franklin learned of his grandson Temple (his only grandson through the male line) while on an extended mission in London, when the boy was about four. He became fond of the young boy, but at first did not tell him of his full identity.[1] He eventually took over custody, returning with the youth to the United States in 1775, and acknowledging their blood relation. A widower by then, Franklin raised the boy in his household.[4]

Paris

Temple, as he was generally known, accompanied his grandfather Benjamin Franklin to France in late 1776. From the age of 16, he worked as secretary to the American diplomatic mission during the American Revolution. Benjamin hoped the trip would round out Temple's education.[5] Along with his cousin Benjamin Franklin Bache, Temple was educated further in France and Switzerland.

A bon vivant, Temple received his highest public appointment as Secretary to the American delegation at the Treaty of Paris in 1782 – 1783, largely through the influence of his grandfather. He never again attained a significant political post in the United States. Benjamin Franklin unsuccessfully lobbied Congress in the hope that Temple would be given a diplomatic post; he believed that, in time, his grandson would succeed him as Ambassador to France.[6] His appeal was rejected for a variety of reasons, including political opposition to Benjamin Franklin and suspicions about Temple's relations with his Loyalist father, who by then was in exile in London. Thomas Jefferson commiserated with Temple over his failure to secure a post, but wrote a letter to James Monroe raising questions about the young man's temperament and abilities.[7]

During the negotiations for the Treaty of Paris, Temple asked one of the British peace commissioners if something could be done for his father. He noted his father's steadfast defense of the Stamp Act, and hoped that the British government might award him a diplomatic post.[8] During 1784, Temple went to London and reconciled with his father, lengthening his stay several times before returning to Paris at the end of the year.[9] In January 1785, Temple received the first airmail in history when a letter from his father was brought across the English Channel by a hot air balloon flown by Jean-Pierre Blanchard and John Jeffries.[3]

Later life

When Benjamin Franklin relinquished his post and sailed home to the United States in 1785, Temple accompanied him. Franklin sent the younger man to see government officials in Philadelphia, to try to recover expenses owed for his time in Paris, but his request was not granted. With his hopes of a diplomatic career at an end, Benjamin Franklin advised Temple to try to develop as a major landowner, since many areas of the country were being settled in rapid postwar development. By this stage Temple was disillusioned. He said that the United States was driven by factions and, if a foreign power were to attempt to conquer the country, they would certainly be successful.[10]

After the elder Franklin died in 1790, Temple lived for a while with his father William in England. In London, he acted as an agent of the American Robert Morris of Philadelphia, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a financier of the American Revolution, and the wealthiest man in the United States. (See Holland Land Company, The Holland Purchase, and The Morris Reserve.) In 1792, Franklin sold 12,000,000 acres (49,000 km2; 19,000 sq mi) of the Phelps and Gorham Purchase east of the Genesee River in New York state to The Pulteney Association, made up of three British investors. There was widespread land speculation in New York after the Revolution, as most of the Iroquois nations, as allies of the British, had been forced to cede their lands to the United States by the postwar treaty. Millions of acres became available for sale to investors, speculators and settlers.

The town and village of Franklinville, in Cattaraugus County (one of the counties formed from land in the Holland Purchase), is presumably named after William Temple Franklin.

Marriage and family

During his first period in France, Temple had an illegitimate son, Théodore, with his mistress, Blanchette Caillot, a married woman.[1] The boy died before reaching age five.[1]

After his return to England and living with his father, Temple Franklin followed in his grandfather's and father's footsteps and had an illegitimate daughter, Ellen (May 15, 1798 London – 1875 Nice, France), with Ellen Johnson D'Evelin, the sister-in-law of his father's second wife, Mary (who had been a widow with children).[11] William Franklin took responsibility for his granddaughter Ellen. Temple moved to Paris, where he lived the remainder of his life and never saw his father again.[12] Temple's daughter, Ellen, eventually was married to Capel Hanbury and had a daughter named Maria Hanbury, who was unmarried and had no children.

When he was living in France again, Temple had a long relationship with Hannah Collyer (1771–1846), an Englishwoman. They finally married a month before his 1823 death, in poverty, in Paris.[1] Temple is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery. Hannah died on 12 December 1846, at age 75, and is buried next to Temple.[13]

Years in France

After his move to France, Franklin continued to act as a real-estate speculator, gaining and losing a fortune.

By his will of 1788, Benjamin Franklin had bequeathed Temple his papers and correspondence, and appointed him as his literary heir. Temple edited and published editions of Franklin's writings, including his well-known Autobiography, published in London and Philadelphia, 1816 – 1819. He published six volumes of papers from 1817 – 1819.[14] Temple Franklin's collected papers are held by the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.[15]

Works

- Edited The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (London and Philadelphia, 1816–1819)

- The Private Correspondence of Benjamin Franklin (1817). A series of letters on miscellaneous, literary, and political subjects, written between the years 1753 and 1790. Comprised and first published from the originals by his grandson William Temple Franklin.[16]

- Edited three-volume Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin, published 1819[1]

See also

Notes

- "William Temple Franklin Papers, 1775-1819" Archived May 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, American Philosophical Society, accessed 4 November 2012

- Stockdale, Eric and Randy J. Holland. Middle Temple Lawyers and the American Revolution. Thompson-West, 2007. p. 41.

- Schiff p. 377

- "Editor Claude-Anne Lopez describes her 'life with Benjamin Franklin'" Archived 2009-04-18 at the Wayback Machine, Yale Bulletin and Calendar, Vol. 28, No. 34, 23 June 2000, accessed 4 November 2012

- Schaeper p. 92

- Schiff pp. 332-335

- Schiff pp. 389-390

- Schiff p. 334

- Schiff pp. 375-477

- Schiff p. 390

- Daniel Mark Epstein (2017), The Loyal Son: The War in Ben Franklin's House

- Sheila L. Skemp (1990) William Franklin: Son of a Patriot, Servant of a King, pp 274

- William Temple Franklin (1762-1823) - Find A Grave Memorial Retrieved 18 January 2018

- "Benjamin Franklin Papers, 1730-1791", American Philosophical Society, accessed 4 November 2012

- Profile and Collected Papers of William Temple Franklin Archived May 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, American Philosophical Society, accessed 4 November 2012

- "Franklin, William Temple (1817). The Private Correspondence of Benjamin Franklin", Henry Colburn. Title page. Accessed 14 April 2020

Bibliography

- Schaeper, Thomas J. France and America in the Revolutionary Era: The Life of Jacques-Donatien Leray de Chaumont, 1725-1803. Berghahn Books, 1995.

- Schiff, Stacy. Benjamin Franklin and the Birth of America. Bloomsbury, 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Temple Franklin. |

- "William Temple Franklin Papers, 1775-1819", American Philosophical Society

- Claude-Anne Lopez, Temple's Diary (2005), a fictional account, highlighting historical events related to the Franklin household and the American Revolution, commissioned by the Independence Hall Association and published on its website: ushistory.org]

- William Temple Franklin at Find a Grave

- The Benjamin Franklin Collection at the Library of Congress includes material taken to London by William Temple Franklin to prepare his three volume work, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin (London: 1817-1818).