Women in rodeo

Historically, women have long participated in the rodeo. Annie Oakley created the image of the cowgirl in the late 19th century, and, in 1908, a 10-year-old girl was dubbed the first cowgirl after demonstrating her roping skills at Madison Square Garden. Women were celebrated competitors in bronc and bull riding events in the early decades of the 20th century until a female bronc rider died in a 1929 rodeo. Her death fueled the growing opposition to female competitors in rodeo; their participation was severely curtailed thereafter.

19th and early 20th centuries

In the 19th century, women learned to rope and ride as the American frontier pushed West, but "cowboying" as a profession was primarily the job of men and paying jobs in the field were essentially non-existent for women. Women were hired as mounted pistol shooters and as trick and stunt horsewomen in Wild West shows of the late 19th century.[1] In 1885, Annie Oakley was hired by Buffalo Bill Cody as a sharpshooter in his Wild West show, but later helped created the iconic image of the cowgirl when she appeared in a western film shot by Thomas Alva Edison in 1894.[2]

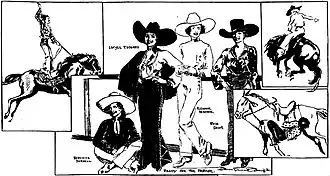

In 1903, women began competing at the Cheyenne Frontier Days, though there was never a large number of female professional riders. Rodeo promoters often advertised female riders as sweethearts or queens of the rodeo.[3] The term cowgirl was first used in the context of a wild west show by Oklahoman Lucille Mulhall in 1908 when, at age 10 years, she displayed her roping skills at Madison Square Garden. Prairie Rose Henderson, bronco buster Mabel Strickland, bucking horse champion Bertha Blankett, and other cowgirls achieved celebrity performing in rodeos of the early 20th century. Women competed at the first indoor rodeo at the Fort Worth, Texas, Coliseum in 1918.[2]

By 1920, women were participating in rodeos as relay racers, trick riders, and rough stock riders.[4] In 1928, one third of all rodeos featured women's competitive events. However, the Cheyenne Frontier Days ended its women's rough stock riding events that year, and in 1929, bronc rider Bonnie McCarroll died during the Pendleton Round-Up when she was thrown from a horse and dragged around the arena, her foot snagged in a stirrup. Until McCarroll's death, cowgirls had been celebrated for their courage and tenacity in the rodeo arena, but the tragedy escalated the growing opposition to women competing in rough stock events. Rodeo promoters began severely curtailing women's competitive participation and encouraged them instead to serve as rodeo queens.[5]

When the Rodeo Association of America (RAA) was formed in 1929 under the direction of Gene Autry,[6] no women's events were included.[7] Women were further marginalized as rodeo competitors with the Great Crash of 1929, and the long, liberal period in American history that had sought to redefine behavior and occupations for American women came to an end. While major rodeos found financial backing during the Great Depression and professional rodeo women found work, chiefly as exhibition riders, small rodeos were put out of business and cowgirls of less than professional abilities were unable to find work. Traditional gender roles were reasserted, and, by 1931, conservatively styled rodeo sponsor contests made their appearance and focused on femininity rather than athleticism. Rodeo women were re-cast as graceful promotional figureheads rather than athletes.[8]

Middle 20th century

The restrictions and limitations of World War II were devastating for professional rodeo women. There were far fewer women than men in rodeo, so women's events were cut.[9] In 1941, Madison Square Garden staged its last women's bronc riding contest.[10] When Gene Autry took control of major rodeos in the early 1940s, he molded them into an event that reflected his "conservative, strongly gendered values". In 1942, he cut women's bronc riding from the New York and Boston rodeos.[11] While women's competition did not immediately cease, exhibitions of riding by celebrated cowgirls began to rise. Male rodeo ignored the women competitors in preference for the pretty but non-athletic "Ranch Girls".[4] Rodeo producer Autry highlighted singers and other entertainers at the expense of competitors and women, who were relegated to barrel racing and vying for titles as rodeo queens.[12]

Pendelton and other rodeos cancelled celebrations because of the war. With professional rodeo women cut from the picture, amateur cowgirls stepped in to fill the void. It was during this period that informal all-girl rodeos were held here and there in the southwest to provide entertainment for the troops.[9] In 1942, Fay Kirkwood staged what was billed as an all-girl rodeo in Bonham, Texas but the program was actually an exhibition rather than a competition. Vaughn Kreig produced an all-girl rodeo about the same time with 8 of its 19 events listed as contests. Neither rodeos featured rodeo queens, perhaps as a general protest against the role of rodeo queens. Cowgirls felt such contests deflected attention from the cowgirl athlete and focused it on the pretty daughters of local boosters instead.[13] Women's barrel racing at Madison Square Garden in 1942 led to that contest's acceptance in rodeo.

A rules dispute during the first all-cowgirl rodeo, in 1948 in Amarillo, Texas,[14] led to the formation of the first rodeo association for women.[15] The dispute, during the calf roping event, concerned a lack of standard rules for the event and led to the formation of the Girls Rodeo Association (GRA) which boasted 74 members and produced one rodeo in its first year. In 1979 the organization was 2,000 strong with 15 sanctioned rodeos. In 1981, the GRA became the Women's Professional Rodeo Association (WPRA)[15] and worked successfully with local rodeo promoters and the PRCA to make women's barrel racing a standard event in most PRCA rodeos.[7] WPRA events are barrel racing, bareback bronc riding, bull or steer riding, team roping, calf roping (both break-away and tie-down), goat tying, and steer un-decorating – a contest in which the mounted cowgirl grabs a ribbon from the steer's neck rather than leaping from her horse and wrestling the steer to the ground. Today, only a fraction of WPRA members compete in the women's rodeos, preferring instead to hit the PRCA rodeos where the purses are larger.[15]

Women are governed by strict rules in WRCA events. Long pants and long-sleeved shirts are required in the arena as well as cowboy boots and hats. Chaps and spurs are usually worn except in the Wild Horse Race and Wild Cow Milking. Animal abuse, unsportsmanlike conduct, and loud, obnoxious profanity are prohibited.[16] The number of women's rodeos decreased in the last decades of the 20th century; the cost of transporting a horse hundreds of miles to compete for the small purses the WPRA offered became economically impractical.[17] Other women's organizations include the Professional Women's Rodeo Association (PWRA) which is opened to female rough stock riders only.[18]

Late 20th and early 21st centuries

A random sample of 1992 WPRA members found more than half had a relative in rodeo, and that most had husbands who were rodeo men. Almost all were in high school or high school graduates with one third having attained college educations.[19]

Notes

- Harris: 37

- Fussell: 70–71

- Bakken: 4

- Groves: 7

- Bakken: 4–5

- Fussell: 71

- Mellis: 123

- Bakken: 6

- Bakken: 7

- Jordan: 195

- Slatta: 317

- Aqulia: 94

- Bakken: 8

- An exhibition billed as "The World's First All-Girl Rodeo" was held earlier in the year at Bonham, Texas but was a cowgirl's Wild West show rather than a competition rodeo. (Jordan, 239).

- Jordan: 239

- Groves: 46

- Jordan: 240

- Groves: 6

- LeCompte: 187

References

- Allen, Michael (1998). Rodeo Cowboys in the North American Imagination. Reno: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 0-87417-315-9.

Rodeo Cowboys in the North American Imagination.

- Aquila, Richard (1996). Wanted Dead or Alive. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02224-6.

- "Protestor Hits Rodeo Queen with Tofu 'Pie'; PETA Member Detained Briefly". Free Online Library. Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- Bakken, Gordon Morris; Brenda Farrington (2003). Encyclopedia of Women in the American West. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-7619-2356-X.

- Broyles, Janell (2006). Barrel Racing. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 1-4042-0543-8.

- Candelaria, Cordelia (2004). Encyclopedia of Latino Popular Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32215-5.

- Cantú, Norma Elia; Olga Nájera-Ramirez (2002). Chicana Traditions. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02701-9.

- Castro, Rafaela (2000). Chicano Folklore. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514639-4.

- "College National Rodeo Finals". Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- Curnutt, Jordan (2001). Animals and the Law. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-147-2.

- Dictionary.com. "Definitions and etymology of rodeo". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- Evans, J. Warren (1981, 1989). Horses. Macmillan. ISBN 0-7167-4255-1. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Fussell, Betty (2008). Raising Steaks. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0151012022.

rodeo women.

- Groves, Melody (2006). Ropes, Reins, and Rawhide. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-3822-4.

- Harris, Moira C. (2007). Rodeo & Western Riding. Edison, NJ: Chartwell Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0785822011.

- International Gay Rodeo Association. "IGRA History".

- Jordan, Teresa (1992) [1982]. Cowgirls. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7575-7.

- Kirsch, George B.; Othello Harris; Claire Nolte (2000). Encyclopedia of Ethnicity and Sports in the United States. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-29911-0.

- Lawrence, Elizabeth Atwood (1982, 1984). Rodeo. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46955-7.

Lawrence Rodeo.

Check date values in:|date=(help) - LeCompte, Mary Lou (2000) [1993]. Cowgirls of the Rodeo. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06874-2.

- Mellis, Allison Fuss (2003). Riding Buffaloes and Broncos. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 123. ISBN 0-8061-3519-0.

Riding Buffaloes and Broncos.

- Merrian Webster (2008). "Rodeo". Merriam Webster, Inc.

- People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). "Buck the Rodeo". People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- Pollack, Howard (1999). Aaron Copland. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-252-06900-5.

Pollack Aaron Copland.

- Regan, Tom; Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson (2004). Empty Cages. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-7425-3352-2.

- Serpell, James (1996). In the Company of Animals. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57779-9.

- Stratton, W.K. (2005, 2006). Chasing the Rodeo. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-603121-3. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Westermeier, Clifford P. (1987) [1947]. Man, Beast, Dust. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4743-5.