Participation of women in the Olympics

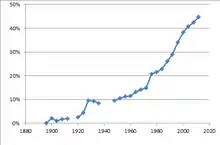

The rate of participation of women in the Olympic Games has been increasing since their first participation in 1900. Some sports are uniquely for women, others are contested by both sexes, while some older sports remain for men only. Studies of media coverage of the Olympics consistently show differences in the ways in which women and men are described and the ways in which their performances are discussed. The representation of women on the International Olympic Committee has run well behind the rate of female participation, and it continues to miss its target of a 20% minimum presence of women on their committee.

| Olympic Games |

|---|

|

| Main topics |

| Games |

History of women at the Olympics

1900

The first Olympic Games to feature female athletes was the 1900 Games in Paris.[1] Hélène de Pourtalès of Switzerland became the first woman to compete at the Olympic Games and became the first female Olympic champion, as a member of the winning team in the first 1 to 2 ton sailing event on May 22, 1900.[2][3] Briton Charlotte Cooper became the first female individual champion by winning the women's singles tennis competition on July 11.[4] Tennis and golf were the only sports where women could compete in individual disciplines. 22 women competed at the 1900 Games, 2.2% of all the competitors.[5] Alongside sailing, golf and tennis, women also competed in croquet. There were several firsts in the women's golf. This was the first time ever that women competed in the Olympic Games. The women's division was won by Margaret Abbott of Chicago Golf Club. Abbott shot a 47 to win and became the first ever American female to win a gold medal in the Olympic Games,[6] though she received a gilded porcelain bowl as a prize instead of a medal. She is also the second overall American woman to receive an Olympic medal. Abbott's mother, Mary Abbott, also competed in this Olympic event and finished tied for seventh, shooting a 65. They were the first and only mother and daughter that have ever competed in the same Olympic event at the same time.[7] Margaret never knew that they were competing in the Olympics; she thought it was a normal golf tournament and died not knowing. Her historic victory was not known until University of Florida professor Paula Welch began to do research into the history of the Olympics and discovered that Margaret Abbott had placed first. Over the course of ten years, she contacted Abbott's children and informed them of their mother's victory.[8][9]

1904–1916

In 1904, the women's archery event was added.[10][11] London 1908 had 37 female athletes who competed in archery, tennis and figure skating.[5] Stockholm 1912 featured 47 women and saw the addition of swimming and diving, as well as the removal of figure skating and archery. The 1916 Summer Olympics were due to be held in Berlin but were cancelled due to the outbreak of World War I.[12]

1920–1928

In 1920, 65 women competed at the Games. Archery was added back to the programme. Paris 1924 saw a record 135 female athletes. Fencing was added to the programme, but archery was removed. 1924 saw the inception of the Winter Olympics where women competed only in the figure skating. Herma Szabo became the first ever female Winter Olympic champion when she won the ladies' singles competition.[13]

At the 1924 Summer Olympics held the same year in Paris, women's fencing made its debut with Dane, Ellen Osiier winning the inaugural gold.[14]

At the 1928 Winter Olympics in St Moritz, no changes were made to any female events. Fifteen year old Sonja Henie won her inaugural of three Olympic gold medals.[15]

The Summer Games of the same year saw the debut of women's athletics and gymnastics.[16] In athletics, women competed in the 100 metres, 800 metres, 4 × 100 metres relay, high jump and discus throw. The 800-metre race was controversial as many competitors were reportedly exhausted or unable to complete the race.[17] Consequently the IOC decided to drop the 800 metres from the programme; it was not reinstated until 1960.[18] Halina Konopacka of Poland became the first female Olympic champion in athletics by winning the discus throw.[19] At the gymnastics competition, the host Dutch team won the first gold medal for women in the sport.[20] Tennis was removed from the program.

1932–1936

For the 1932 Summer Olympics, held in Los Angeles, the javelin throw was added. At the 1936 Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, women competed in the alpine skiing combined event for the first time, with German Christl Cranz winning the gold medal.[21] At the 1936 Summer Olympics held in Berlin, gymnastics returned to the programme for women.

1940–1944

The 1940 Winter Olympics due to be held in Sapporo, 1940 Summer Olympics due to be held in Tokyo, 1944 Winter Olympics due to be held in Cortina d'Ampezzo and the 1944 Summer Olympics due to be held in London were all cancelled due to the outbreak of World War II. Six female Olympic athletes died due to World War II:[22]

| Athlete | Nation | Sport | Year of competition | Medal(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estella Agsteribbe | Netherlands | Gymnastics | 1928 | |

| Dorothea Köring | Germany | Tennis | 1912 | |

| Helena Nordheim | Netherlands | Gymnastics | 1928 | |

| Anna Dresden-Polak | Netherlands | Gymnastics | 1928 | |

| Jud Simons | Netherlands | Gymnastics | 1928 | |

| Hildegarde Švarce | Latvia | Figure Skating | 1936 |

1948–1956

At the 1948 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz, women made their debut in the downhill and slalom disciplines, having only competed in the combined event in 1936. In 1948, women competed in all of the same alpine skiing disciplines as the men. Barbara Ann Scott of Canada won the ladies' singles figure skating competition, marking the first time a non-European won the gold medal in the event.[23] At the London 1948 Summer Olympics, women competed in canoeing for the first time.[24] The women competed in the K-1 500 metres discipline.[24] At the 1952 Winter Olympics held in Oslo, women competed in cross-country skiing for the first time. They competed in the 10 kilometre distance. At the 1952 Summer Olympics held in Helsinki, women were allowed to compete in equestrian for the first time.[25] They competed in the dressage event which was co-ed with the men.[25] Danish equestrian Lis Hartel of Denmark won the silver medal in the individual competition alongside men.[26] At the 1956 Winter Olympics held in Cortina d'Ampezzo, the 3 × 5 kilometre relay cross country event was added to the program. The 1956 Summer Olympics held in Melbourne, had a programme identical to that of the prior Olympiad.[note 1]

1960–1968

The 1960 Winter Olympics held in Squaw Valley saw the debut of speed skating for women.[27] Helga Haase, representing the United Team of Germany won the inaugural gold medal for women in the competition after winning the 500 metres event.[28] The programme remained the same for the 1960 Summer Olympics held in Rome. At the 1964 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck, the women's 5km cross-country skiing event debuted.[29] At the 1964 Summer Olympics held in Tokyo, Volleyball made its debut with the host Japanese taking the gold.[30] At the 1968 Winter Olympics held in Grenoble, women's luge appeared for the first time. Erika Lechner of Italy won the gold after East German racers Ortrun Enderlein, Anna-Maria Müller and Angela Knösel allegedly heated the runners on their sleds and were disqualified.[31] Whether the East Germans actually heated their sleds or if the situation was fabricated by the West Germans remains a mystery.[32] At the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, women competed in shooting for the first time.[33] The women competed in mixed events with the men and were allowed to compete in all seven disciplines.[33]

1972–1980

The 1972 Winter Olympics held in Sapporo saw no additions or subtractions of events for women. At the 1972 Summer Olympics held in Munich, archery was held for the first time since 1920.[34] At the 1976 Winter Olympics in Innsbruck, ice dancing was added to the programme.[note 2] Women competed in three new events at the 1976 Summer Olympics held in Montreal. Women debuted in basketball and handball.[35][36] Women also competed for the first time in rowing, participating in six of the eight disciplines.[37] There were no new events for women at the 1980 Winter Olympics held in Lake Placid. At the 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow, women's field hockey debuted. The underdog Zimbabwean team pulled off a major upset, winning the gold, the nation's first ever Olympic medal.[38] However, these Olympics were marred by the US-led boycott of the games due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.[39]

1984–1992

The women's 20 kilometre cross-country skiing event was added to the programme for the 1984 Winter Games in Sarajevo. Marja-Liisa Hämäläinen of Finland dominated the cross-country events, winning gold in all three distances.[40]

Multiple new events for women were competed in at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Synchronized swimming made its debut, with only women competing in the competition.[41] The host Americans won gold in both the solo and duet events.[42] Women also made their debut in cycling, competing in the road race.[43] This event was also won by an American, Connie Carpenter.[43] Also, rhythmic gymnastics appeared for the first time with only women competing. Canadian Lori Fung won the competition.[44] The women's marathon also made its first appearance in these Games, with American Joan Benoit winning gold.[45] These were also the first Games where women competed only against other women in shooting.[46] These games were boycotted by the Soviet Union and its satellite states.

There were no new events at the 1988 Winter Olympics held in Calgary. At the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, table tennis appeared for the first time for both men and women.[47] They competed in the singles and doubles disciplines. Also, a female specific sailing event debuted at these Games, the women's 470 discipline.[48] For the first time women competed in a track cycling event, the sprint.[49]

In 1991, the IOC made it mandatory for all new sports applying for Olympic recognition to have female competitors.[50] However, this rule only applied to new sports applying for Olympic recognition. This meant that any sports that were included in the Olympic programme prior to 1991 could continue to exclude female participants at the discretion of the sport's federation.[51] At the 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville, women competed in biathlon for the first time.[52] The athletes competed in the individual, sprint and relay disciplines. Freestyle skiing also debuted at the 1992 Games, where women competed in the moguls discipline.[53] Short track speed skating first appeared at these Games.[54] Women competed in the 500 metres and the 3000 metre relay. At the 1992 Summer Olympics held in Barcelona, badminton appeared on the programme for the first time.[55] Women competed in the singles and doubles competition.[55] Women also competed in the sport of judo for the first time at these Games.[56] 35 nations still sent all-male delegations to these Games.[57]

1994–2002

At the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, the aerials discipline of freestyle skiing officially debuted.[58] Lina Cheryazova of Uzbekistan won the gold medal, which is to date her nation's sole medal at an Olympic Winter Games.[59] Women's soccer and softball made their first appearances at the 1996 Games in Atlanta, where the hosts won gold in both.[60][61] At the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, ice hockey (with the United States winning gold) and curling debuted for women.[62][63] Numerous new events made their premieres at the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney. Weightlifting, modern pentathlon, taekwondo, triathlon and trampoline all debuted in Australia.[64] At the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, women's bobsleigh made its first appearance.[65] Jill Bakken and Vonetta Flowers of the USA won the two-woman competition, the sole bobsleigh event for women at the 2002 Games.[66]

2004–2012

.jpg.webp)

At the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, women appeared in wrestling for the first time competing in the freestyle weight classes of 48 kg, 55 kg, 63 kg and 72 kg.[67][68] Women also competed in the sabre discipline of fencing for the first time,[69] with Mariel Zagunis of the USA winning gold.[70] In 2004, women from Afghanistan competed at the Olympics for the first time in their history after the nation was banned from Sydney 2000 by the IOC due to the Taliban government's opposition to women in sports.[71] At the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, the programme remained unchanged. At the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, a few new events were added. BMX cycling was held for the first time in 2008, debuting with the men's event.[72] Women also competed in the 3000 m steeplechase and the 10 kilometre marathon swim for the first time.[46][73] Baseball and boxing remained the only sports not open to women at these Games.

At the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, ski cross debuted for both women and men.[74] Ashleigh McIvor of Canada won the inaugural gold for women in the sport.[75] Controversy was created when women's ski jumping was excluded from the programme by the IOC due to the low number of athletes and participating nations in the sport.[76] A group of fifteen competitive female ski jumpers later filed a suit against the Vancouver Organizing Committee for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games on the grounds that it violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms since men were competing in the same event.[77] The suit failed, with the judge ruling that the situation was not governed by the Charter.[78] The 2012 Summer Olympics saw women's boxing make its debut.[79] This, combined with the decision by the IOC to drop baseball from the programme for 2012, meant that women competed in every sport at a Summer Games for the first time.[80] London 2012 also marked the first time that all national Olympic committees sent a female athlete to the Games.[81] Brunei, Saudi Arabia and Qatar all had female athletes as a part of their delegations for the first time.[82]

2014–2018

At the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, women's ski jumping made its first appearance.[83] Carina Vogt of Germany won the first gold medal for women in the sport.[84] The 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro saw the first rugby sevens competition.[85] The tournament was won by the Australian team.[86] Golf was also re-added to the programme for the first time for women since 1900.[87] Inbee Park of South Korea won the tournament.[88] The 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang saw the addition of big air snowboarding, mixed doubles curling, mass start speed skating, and mixed team alpine skiing.[89][90] Jamie Anderson of the USA was the silver medalist of the big air, also winning gold in slopestysle, becoming the most medaled female snowboarder at those games.

Future

Women will compete in softball, karate, sport climbing, surfing, and skateboarding at the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo.[91] The International Ski Federation has stated that they are aiming to include women's Nordic combined in the Olympic programme for the first time at the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.[92]

Sports

Women have competed in the following sports at the Olympic Games.[93]

| Sport | Year added to the programme |

|---|---|

| Tennis | 1900 |

| Golf | 1900 |

| Sailing | 1900/1988[note 3] |

| Archery | 1904 |

| Figure skating | 1908 |

| Diving | 1912 |

| Swimming | 1912 |

| Fencing | 1924 |

| Athletics | 1928 |

| Alpine skiing | 1936 |

| Cross-country skiing | 1936 |

| Canoeing | 1948 |

| Equestrian | 1952 |

| Speed skating | 1960 |

| Volleyball | 1964 |

| Luge | 1964 |

| Shooting | 1968 |

| Basketball | 1976 |

| Handball | 1976 |

| Rowing | 1976 |

| Field hockey | 1980 |

| Cycling | 1984 |

| Table tennis | 1988 |

| Badminton | 1992 |

| Biathlon | 1992 |

| Judo | 1992 |

| Short track speed skating | 1992 |

| Football | 1996 |

| Softball | 1996 |

| Soccer | 1996 |

| Curling | 1998 |

| Ice hockey | 1998 |

| Modern pentathlon | 2000 |

| Taekwondo | 2000 |

| Triathlon | 2000 |

| Water polo | 2000 |

| Weightlifting | 2000 |

| Bobsleigh | 2002 |

| Skeleton | 2002 |

| Wrestling | 2004 |

| Boxing | 2012 |

| Ski jumping | 2014 |

| Rugby | 2016 |

Gender differences

Athletics

In combined events at the Olympics, women compete in the seven-event heptathlon but men compete in three more events in the decathlon.[94] A women's pentathlon was held from 1964 to 1980, before being expanded to the heptathlon.

In sprint hurdles at the Olympics, men compete in the 110 metres hurdles, while women cover 100 metres.[94] Women ran 80 metres up to the 1968 Olympics; this was extended to 100 metres in 1961, albeit on a trial basis, the new distance of 100 metres became official in 1969. No date has been given for the addition of the 10 metres.[94] Both men and women clear a total of ten hurdles during the races and both genders take three steps between the hurdles at elite level.[95] Any amendment to the women's distance to match the men's would impact either the athlete technique or number of hurdles in the event, or result in the exclusion of women with shorter strides.

Historically, women competed over 3000 metres until this was matched to the men's 5000 metres event in 1996. Similarly, women competed in a 10 kilometres race walk in 1992 and 1996 before this was changed to the standard men's distance of 20 km. The expansion of the women's athletics programme to match the men's was a slow one. Triple jump was added in 1996, hammer throw and pole vault in 2000, and steeplechase in 2008. The sole difference remaining is the men-only 50 kilometres race walk event.[96] While the inclusion of a women's 50 km event has been advocated, proposals have also been mooted to remove the men's event entirely from the Olympics.[97][98]

Boxing

At the summer Olympics, men's boxing competitions take place over three three-minute rounds and women's over four rounds of two minutes each.[99] Women also compete in three weight categories against 10 for men.[94]

Canoeing

Canoeing excludes women at the Olympics for both the sprint and slalom disciplines.[100] These events will be contested at the next Olympic Games in Tokyo in 2020.[101]

Shooting

Women are excluded from the 25 metres rapid fire pistol, the 50 metres pistol and the 50 metres rifle prone events.[102] Men are excluded from the 25 metres pistol event.[102] From 1996 to 2004, women participated in the double trap competition. The women's event was taken off the Olympic program after the 2004 Summer Olympics.[103] Final shooting for women was discontinued in international competition as a result.

Road cycling

Since 1984, when women’s cycling events were introduced, the women's road race has been 140 kilometres to the men's 250 kilometres. The time trials are 29 kilometres and 44 kilometres respectively. Each country is limited to sending five men and four women to the Summer Games.[94]

Tennis

In common with the Grand Slams women compete in three set matches at the Olympics as opposed to five sets for men.[94]

Soccer

In Olympic soccer, there is no age restriction for women, whereas the men's teams field under 23 teams with a maximum of three over aged players.[104]

Gender equality

Historically, female athletes have been treated, portrayed and looked upon differently from their male counterparts. In the early days of the Olympic Games, many NOCs sent fewer female competitors because they would incur the cost of a chaperone, which was not necessary for the male athletes.[105] While inequality in participation has declined throughout history, women are still sometimes treated differently at the Games themselves.[106] For example, in 2012, the Japan women's national soccer team travelled to the Games in economy class, while the men's team travelled in business class.[107] Although women compete in all sports at the summer Olympics, there are still 39 events that are not open to women.[108]

Media

Historically, coverage and inclusion of women's team sports in the Olympics has been limited. It has been shown that commentators are more likely to refer to female athletes using "non-sporting terminology" than they are for men.[109] A 2016 study published by Cambridge University Press found that women were more likely to be described using physical features, age, marital status and aesthetics than men were, as opposed to sport related adjectives and descriptions.[110] The same study found that women were also more likely to be referred to as "girls" than men were to be called "boys" in commentary.[111] This disparity in the quality of coverage for women's Olympic sports has been attributed to the fact that 90% of sports journalists are male.[112]

Role of the International Olympic Committee

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was created by Pierre, Baron de Coubertin, in 1894 and is now considered "the supreme authority of the Olympic movement".[113] Its headquarters are located in Lausanne, Switzerland. The title of supreme authority of the Olympic movement consists of many different duties, which include promoting Olympic values, maintaining the regular celebration of the Olympic Games, and supporting any organization that is connected with the Olympic movement.[113]

Some of the Olympic values that the IOC promotes are practicing sport ethically, eliminating discrimination from sports, encouraging women's involvement in sport, fighting the use of drugs in sport, and blending sport, culture, and education.[113] The IOC supports these values by creating different commissions that focus on a particular area. These commissions hold conferences throughout the year where different people around the world discuss ideas and ways to implement the Olympic values into the lives of people internationally.[113] The commissions also have the responsibility of reporting their findings to the President of the IOC and its executive board.[113] The President has the authority to assign members to different commissions based on the person's interests and specialties.

The first two female IOC members were the Venezuelan Flor Isava-Fonseca and the Norwegian Pirjo Häggman and were co-opted as IOC members in 1981.[114]

The IOC can contain up to 115 members, and currently, the members of the IOC come from 79 different countries.[113] The IOC is considered a powerful authority throughout the world as it creates policies that become standards for other countries to follow in the sporting arena.[115]

Only 20 of the current 106 members of the IOC are women.[116]

Women in Sport Commission

A goal of the IOC is to encourage these traditional countries to support women's participation in sport because two of the IOC's Olympic values that it must uphold are ensuring the lack of discrimination in sports and promoting women's involvement in sport. The commission that was created to promote the combination of these values was the Women in Sport Commission.[117] This commission declares its role as "advis[ing] the IOC Executive Board on the policy to deploy in the area of promoting women in sport".[117] This commission did not become fully promoted to its status until 2004, and it meets once a year to discuss its goals and implementations.[117] This commission also presents a Women and Sport Trophy annually which recognizes a woman internationally who has embodied the values of the IOC and who has supported efforts to increase women's participation in sport at all levels.[115] This trophy is supposed to symbolize the IOC's commitment to honoring those who are beneficial to gender equality in sports.[118]

Another way that the IOC tried to support women's participation in sport was allowing women to become members. In 1990 Flor Isava Fonseca became the first woman elected to the executive board of the IOC. The first American woman member of the IOC was Anita DeFrantz, who became a member in 1986[119] and in 1992 began chairing the prototype of the IOC Commission on Women in Sport. DeFrantz not only worked towards promoting gender equality in sports, but she also wanted to move toward gender equality in the IOC so women could be equally represented. She believed that without equal representation in the IOC that women's voices would not get an equal chance to be heard. She was instrumental in creating a new IOC policy that required the IOC membership to be composed of at least 20 percent women by 2005.[119] She also commissioned a study conducted in 1989 and again in 1994 that focused on the difference between televised coverage of men's and women's sports.[119] Inequality still exists in this area, but her study was deemed to be eye opening to how substantial the problem was and suggested ways to increase reporting on women's sporting events. DeFrantz is now head of the Women in Sport Commission.

The IOC failed in its policy requiring 20 percent of IOC members to be women by 2005.[116] By June 2012 the policy had still not been achieved, with only 20 out of 106 IOC members women, an 18.8 percent ratio. Only 4 percent of National Olympic Committees have female presidents.[116]

Impact of the Women's World Games

Background

In 1919, French feminist, translator and amateur rower, Alice Milliat initiated talks with the IOC and International Association of Athletics Federations with the goal of having women's athletics included at the 1924 Summer Olympics.[120] After her request was refused, she organized the first "Women's Olympiad", hosted in Monte Carlo.[121] This would become the precursor to the first Women's World Games. The event was seen as a protest against the IOC's refusal to include females in athletics and a message to their President Pierre de Coubertin who was opposed to women at the Olympics.[122] Milliat went on to found the International Women's Sports Federation who organized the first Women's World Games.

Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the International Olympic Committee

The Games

The first ever "Women's Olympic Games" were held in Paris in 1922. The athletes competed in eleven events:[123] 60 metres, 100 yards, 300 metres, 1000 metres, 4 x 110 yards relay, Hurdling 100 yards, high jump, long jump, standing long jump, javelin and shot put. 20,000 people attended the Games and 18 world records were set.[124] Despite the successful outcome of the event, the IOC still refused to include women's athletics at the 1924 Summer Olympics. On top of this, the IOC and IAAF objected to the use of the term "Olympic" in the event, so the IWSF changed the name of the event to the Women's World Games for the 1926 version.[125] The 1926 Women's World Games would be held in Gothenburg, Sweden. The discus throw was added to the programme. These Games were also attended by 20,000 spectators and finally convinced the IOC to allow women to compete in the Olympics in some athletics events.[126] The IOC let women compete in 100 metres, 800 metres, 4 × 100 metres relay, high jump and discus throw in 1928.[127] There would be two more editions of the Women's World Games, 1930 in Prague and 1934 in London.[128] The IWSF was forced to fold after the Government of France pulled funding in 1936.[129]

See also

Notes

- The equestrian events for these Games were held in Stockholm due to Australia's strict equine quarantine laws.

- Ice dancing is a pairs event with one male and one female.

- All sailing events were open to women from 1900 to 1984 (except 1948). Women-only events were introduced in 1988.

References

- "Women at the Olympics". Pontifical Council for the Laity. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- "Women at the Olympic Games". topendsports.com. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- Lygkas, Giannis. "1900 Summer Olympics - The Results (Sailing) - Sport-Olympic.com". sport-olympic.gr. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- "Tennis at the 1900 Paris Summer Games: Women's Singles". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- "FACTSHEET THE GAMES OF THE OLYMPIAD" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. October 28, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- "Margaret ABBOTT - Olympic Golf | United States of America". February 16, 2017.

- "Margaret Abbott Won an Olympic Medal in 1900, but Never Found Out". August 10, 2016.

- "Margaret Abbott Aced Team USA's First Women's Olympic Gold Medal and Didn't Know It".

- "Women Golfers' Museum".

- "Archery at the 1904 St. Louis Summer Games". Sports-Reference.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Andrews, Evan (August 29, 2014). "8 Unusual Facts About the 1904 St. Louis Olympics – History in the Headlines". HISTORY.com. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Faris, Nick (August 3, 2016). "The Games that never were: How Germany almost hosted the 1916 Olympics — in the middle of a war". National Post. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- Walter, Pachl (August 17, 2009). "Szabo, Herma". Austria-Forum (in German) (March 25, 2016 ed.). Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "Olympic History for Families". users.skynet.be (December 22, 2000 ed.). February 10, 2000. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- "Sonja Henie". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. April 2, 2014. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- "Timeline of Women in Sports". faculty.elmira.edu. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- Emery, Lynne. "An Examination of The 1928 Olympic 800 Meter Race For Women" (PDF). la84.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- Guthrie, Sharon Ruth; Costa, D. Margaret (1994). Women and Sport: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Human Kinetics. pp. 127–128. ISBN 9780873226868.

- Petruczenko, Maciej (May 17, 2017). "Halina Konopacka – pierwsza dama Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej – wciąż czeka na Order Orła Białego". Onet Sport (in Polish). Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- Price, Jessica Taylor (December 11, 2012). "Our First Olympics: Women's Gymnastics at Amsterdam 1928". The Gymternet. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Boucher, Marc. "The Garmisch Partenkirchen 1936 Olympic Winter Games sport result: alpine skiing". marcolympics.org. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Olympians Who Were Killed or Missing in Action or Died as a Result of War". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Schrodt, Barbara (September 30, 2012). "Barbara Ann Scott". The Canadian Encyclopedia (March 4, 2015 ed.). Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Lopez, Cesar (March 30, 2016). "Canoe/Kayak 101: Olympic history". NBC Olympics. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "Unique, Bizarre and Memorable Olympic Equestrian Moments – Part I". Horse Canada. August 5, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "Dressage individuel Mixed – Equestrian at the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki – Results". olympiandatabase.com. Sportsencylco. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- Morrison, Mike; Frantz, Christine. "Winter Olympics: Speed Skating". Infoplease. Sandbox Networks, Inc. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "500 m W – Speed Skating at the 1960 Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley – Results". olympiandatabase.com. Sportsencyclo. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Innsbruck 1964 Olympic Winter Games". Encyclopædia Britannica. March 17, 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Okamoto, Mitsuo. "Olympic Games Volleyball Tournament". geocities.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Boucher, Marc. "The Grenoble 1968 Olympic Winter Games sport result: luge". marcolympics.org. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "Luge at the 1968 Grenoble Winter Games: Women's Singles". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Woolum, Janet (1998). Outstanding Women Athletes: Who They are and how They Influenced Sports in America. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 52. ISBN 9781573561204.

- "Archery Facts". softschools.com. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- "Games of the XXIst Olympiad – 1976". USA Basketball. February 20, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "Handball Tournaments at the Montreal 1976 Olympic Games". International Handball Federation. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Guerin, Andrew. "1976 Montreal Olympic Games". Australian Rowing History. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2017.

- Bulla, Fatima (April 12, 2015). "#1980SoFarSoGood: So Zimbabwe, so gold!…Golden Girl relives 1980 Moscow Olympics". The Sunday Mail. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- "The Olympic Boycott, 1980". 2001-2009.state.gov. May 8, 2008. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- "The Official Report of the Organising Committee of the XlVth Winter Olympic Games 1984 at Sarajevo" (PDF). Sarajevo 1984: 1–198.

- Gibson, Megan (July 6, 2012). "9 Really Strange Sports That Are No Longer in the Olympics". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "U.S. Synchronized Swimming History". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- O'Toole, Kelley (September 1, 2016). "Reliving The Magic of the First Women's Olympic Cycling Race". BICYCLIST: SoCal and Beyond. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Los Angeles 1984". Canadian Olympic Committee. August 10, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Robinson, Roger (August 5, 2014). "The Legacy of Joan Benoit Samuelson's Olympic Marathon Win". Runner's World. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Summer Olympics Competitions Fast Facts". CNN. July 31, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- Hanagudu, Ashwin (August 5, 2016). "Olympic Table Tennis Women: Gold Medal winners so far (1988–2012)". Sportskeeda. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Olympic Sailing". Australian Sailing Team. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved August 12, 2017.

- "Track Cycling at the Olympics". topendsports.com. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- Patel, Seema (April 24, 2015). Inclusion and Exclusion in Competitive Sport: Socio-Legal and Regulatory Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 9781317686330.

- Loney, Heather (February 11, 2014). "Women's ski jumping makes historic Olympic debut". Global News. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- "Women in Biathlon (history)". Biathlon Canada. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "History". Freestyle Canada. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "Short Track History". Speed Skating Canada. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "Badminton – the Olympic Journey". Badminton World Federation. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Nicksan, Philip (August 3, 1992). "OLYMPICS / Barcelona 1992: Judo: Painful end for brave Briggs". The Independent. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Al-Ahmed, Ali (May 19, 2008). "Bar countries that ban women athletes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- Davis, Fred; Berton, Pierre; Fotheringham, Allan; Kennedy, Betty; Webster, Jack; Laroche, Philippe (January 8, 1994). "Freestyle skiing goes Olympic". Front Page Challenge. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- Ian, Buchanan; Mallon, Bill (2005). Historical Dictionary of the Olympic Movement (3rd ed.). Scarecrow Press. pp. 306–307. ISBN 9780810865242. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- Dure, Beau (July 29, 2016). "Where Are They Now? USWNT's 1996 Olympic team". FourFourTwo. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- Hughes, Amy (July 19, 2011). "History lesson". NCAA.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- McGourty, John (January 29, 2010). "Impact of 1998 women's team can still be felt today". National Hockey League. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- "Curling at the Olympic Games". World Curling Federation. Archived from the original on February 11, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- "Sydney 2000 Olympic Games". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. June 21, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "US women grab first bobsleigh gold". BBC Sport. February 20, 2002. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- "2002 Olympic Team". United States Olympic Committee. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- Caple, Jim (July 15, 2004). "Women's wrestling makes Olympic debut". ESPN. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- Weitekamp, Jeff (November 18, 2003). "Early 2004 U.S. Olympic Team Trials – Wrestling preview for women's freestyle". TheMat.com. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- Harkins, Craig (April 26, 2004). "USFA Announces the 2004 Olympic Fencing Team". Fencing.net. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Yahoo! Sports Athens 2004 Summer Olympics Fencing Results". Yahoo Sports. August 17, 2004. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- Donegan, Lawrence (August 19, 2004). "Forty-two seconds that put Afghan women on the map". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "USA Cycling announces 2008 U.S. Olympic Team". USA Cycling. July 1, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Marathon Swimming". British Swimming. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- "Ski cross to debut at Vancouver 2010 Olympics". CTVNews. February 3, 2008. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- Shifman, Jordan (November 16, 2012). "Ski cross Olympic gold medallist Ashleigh McIvor retires". CBC Sports. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- "IOC approves skicross; rejects women's ski jumping". International Herald Tribune. November 28, 2006. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- "Why Can't Women Ski Jump?". Time. February 11, 2010. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- "Female ski jumpers lose Olympic battle". CBC News. July 10, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2017.

- Blount, Rachel (August 5, 2017). "Women's boxing makes Olympic debut to sellout crowd". Gilroy Dispatch. Archived from the original on October 16, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- Scott-Elliot, Robin (July 26, 2012). "London 2012 Olympics: The women's Games". The Independent. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- "Saudi women to compete in Games". BBC News. July 12, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- Byrd, David (July 12, 2012). "Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Brunei to Send Women to Olympics". VOA. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- Hart, Simon (February 11, 2017). "Sochi Winter Olympics 2014: Carina Vogt wins women's ski jumping gold". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- Hodgetts, Rob (February 11, 2014). "Sochi 2014: Carina Vogt wins women's ski jumping gold". BBC Sport. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- Shiekman, Mike (August 12, 2012). "2016 Olympics: New Events Debuting in Rio". Bleacher Report. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Galloway, Patrick (July 27, 2017). "Aussie Olympic gold leads to national women's sevens tournament". ABC News. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Matuszewski, Erik (August 7, 2016). "Ten Things To Know As Golf Returns To Olympics After 112-Year Absence". Forbes. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Mell, Randall (August 21, 2016). "Inbee Park's Gold-Medal Performance Captivates a Nation". Golf Channel. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- "Snowboarding, curling mixed doubles among new sports added to 2018 Winter Olympics". Sports Illustrated. June 8, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- "Winter Olympics: Big air, mixed curling among new 2018 events". BBC Sport. June 8, 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- "You're in! Baseball/softball, 4 other sports make Tokyo cut". USA Today. August 3, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- Pavitt, Michael (October 3, 2016). "FIS target Nordic Combined women's competition at Beijing 2022". Inside the Games. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- "Women in the Olympic Movement" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. January 22, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- Davies, Lizzy (August 10, 2012). "London 2012: not all Olympians compete on an equal footing". The Guardian. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Rhythmic Hurdling: The Search for the Holy Grail. USTFCCCA. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- 50 Kilometres Race Walk. IAAF. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Kelly, Daniel (April 17, 2017). 50 km race may be removed from the Olympic program. Off The Ball. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Philips, Mitch (April 13, 2017). Athletics – 50km walk to stay in Olympics. Reuters. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Rafael, Dan (April 14, 2017). "Adams to fight same 3-minute rounds as men". ESPN. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- "ICF Approves New Race Program for 2020 Olympics – Includes 3 Women's Canoe Events". WomenCAN International. January 14, 2016. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- Miller, Ian (January 15, 2016). "ICF approves new race programs for the 2020 Olympic Games". canoekayak.ca. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- Shooting. International Olympic Committee

- "Kim Rhode". USA Shooting. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "What are the rules for Olympics men's soccer?". Fox Sports. August 4, 2016. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- Longman, Jere (June 23, 1996). "How the Women Won". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Ryall, Julian (July 18, 2012). "London 2012 Olympics: sexism row as Japan's female athletes fly lower class". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- McCurry, Justin (July 19, 2012). "Japan's female athletes fly economy while men's team sit in business". The Guardian. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Donnelly, Peter; Donnelly, Michele K. (September 2013). "The London 2012 Olympics: A Gender Equality Audit" (PDF). utoronto.ca. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- Young, Henry (August 3, 2016). "Gender divides in the language of sport". CNN. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- "Aesthetics over athletics when it comes to women in sport". University of Cambridge. August 12, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- Plank, Liz (August 19, 2016). "What if we judged sexist sport coverage as an Olympic sport?". Vox. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- Morrison, Sara (February 19, 2014). "Media is 'failing women' – sports journalism particularly so". Poynter. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "IOC: The Organisation". Olympic Movement. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Women in the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: An Analysis of Participation and Leadership Opportunities" (PDF). SHARP Center for Women and Girls: 1–76. April 2013.

- Division for the Advancement of Women of the United Nations Secretariat (December 2007). "Women, Gender Equality and Sport" (PDF). Women 2000 and Beyond: 2–40.

- "Women in the Olympic movement" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- "Women in Sport Commission". International Olympic Committee. October 27, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- "IOC celebrates the power of Women in Sport, honors coaches in new Lifetime Achievement Awards". International Sports Press Association. November 11, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- Sharp, Kathleen (1996). "Unsung Heroes". Women's Sports and Fitness. 18 (5): 64.

- Quintillan, Ghislaine. "Alice Milliat and the Women's Games" (PDF). Olympic Review. ISSN 0251-3498. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Blickenstaff, Brian (August 11, 2017). "Throwback Thursday: How a French Feminist Staged Her Own Games and Forced the Olympics to Include Women". Vice Sports. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Kidd, Bruce (Spring 1994). "The Women's Olympic Games: Important Breakthrough Obscured By Time". Canadian Association for the Advancement of Women and Sport and Physical Activity. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Tuttle, Jane (2002). "Complete results of the First International Track Meet for Women". They Set the Mark. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Sylvain, Charlet (November 3, 2008). "Chronique de l'athlétisme féminin". home.nordnet.fr (in French). Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "Women's World and European Games". gbrathletics. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Parčina, Ivana; Šiljak, Violeta; Perović, Aleksandra; Plakona, Elena (2014). "Women's World Games" (PDF). Physical Education and Sport Through the Centuries: 49–60. ISSN 2335-0660.

- Boykoff, Jules (July 26, 2016). "The Forgotten History of Female Athletes Who Organized Their Own Olympics". Bitch Media. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- "When Women Were Denied From The Olympics, A Women's-Only Version Emerged". Curiosity.com. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- Goss, Sara (June 17, 2016). "Alice Milliat and the Women's Olympic Games". wispsports.com. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

Bibliography

- Australian Sport Commission; Office of the Status of Women (1985). Women, Sport and the Media. Australian Government Publishing Services. ISBN 978-0-644-04155-3.

- "Wickenheiser signs with Swedish men's club". CBC Sports. The Canadian Press. July 22, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- "Canadians cheer new Olympic sports". Waterloo Region Record. The Canadian Press. July 27, 1992.

- Community, Sport and Cultural Development – Province of British Columbia (2011). "BC ATHLETE ASSISTANCE PROGRAM 2010 – 2011 Provincial Sport Organization Guidelines, Policies and Procedures" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- Crocombe, R G (2007). Asia in the Pacific Islands : replacing the West. CIPS Publications, University of the South Pacific. ISBN 978-982-02-0388-4. OCLC 213886360.

- Dyer, K F (1982). Challenging the Men, The social biology of female sporting achievement. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-1652-7.

- First National Bank (2010). "School Sport LOCAL SPORT INITIATIVES". Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- Howell, Reet; Howell, Max (1988). Aussie Gold, A celebration of every Australian Olympic Gold Medal since 1896. Melbourne, Victoria: Brooks-Waterloo. ISBN 978-0-86440-680-4.

- "The sports on the Olympic programme" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. February 2008. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- International Softball Federation. "The History of Softball". International Softball Federation. Archived from the original on December 12, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- International Softball Federation (September 5, 2006). "USA Wins 2006 Women's World Championship". International Softball Federation. Archived from the original on March 4, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- International Softball Federation (August 4, 2002). "Four Teams Qualify for 2004 Olympic Games". International Softball Federation. Archived from the original on October 25, 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- Cooky, Cheryl; Messner, Michael; Musto, Michela (June 5, 2015). ""It's Dude Time!": A Quarter Century of Excluding Women's Sports in Televised News and Highlight Shows". Communication & Sport. 3 (3): 261–287. doi:10.1177/2167479515588761.

- Jones, Diane (February 2004). "Half the Story? Olympic Women on the ABC News Online" (PDF). Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy (110): 132–146. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- Maraniss, David (2008). Rome 1960. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-3407-5.

- Massoa, Prisca; Fasting, Kari (December 2002). "Women and sport in Tanzania". In Pfister, Gertrud; Hartmann-Tews, Ilse (eds.). Sport and Women: Social Issues in International Perspective. International Society for Comparative Physical Education & Sport. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24628-6.

- "An Agreement By Nagano Games". The New York Times. November 29, 1992. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- Ormsby, Mary (November 18, 1992). "Women 's hockey gets approval for '98". Toronto Star.

- Pfister, Gertrud; Hartmann-Tews, Ilse (December 2002). "Women's inclusion in sport, International and comparative findings". In Pfister, Gertrud; Hartmann-Tews, Ilse (eds.). Sport and Women: Social Issues in International Perspective. International Society for Comparative Physical Education & Sport. Routledge. pp. 267–280. ISBN 978-0-415-24628-6.

- Singapore National Olympic Council. "The 117th IOC Session in Singapore - A Summary". Singapore National Olympic Council. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- sports-reference.com (2006). "Ice Hockey at the 2006 Torino Winter Games: Women's Ice Hockey". sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- Symons, Carol; Hemphill, Dennis (November 2006). "Netball and transgender participation". In Caudwell, Jayne (ed.). Sport, sexualities and queer/theory. Routledge Critical Studies in Sport. Routledge. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-415-36761-5.

- Yen, Yi-Wyn (February 20, 2008). "Canada's leading star". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved March 1, 2009.