Women rabbis and Torah scholars

Women rabbis are individual Jewish women who have studied Jewish Law and received rabbinical ordination. Women rabbis are prominent in Progressive Jewish denominations, however, the subject of women rabbis in Orthodox Judaism is more complex. Although Orthodox women have been ordained as rabbis,[1][2] many major Orthodox Jewish communities and institutions do not accept the change.[3][4][5] In an alternative approach, other Orthodox Jewish institutions train women as Torah scholars for related Jewish religious roles. These roles typically involve training women as religious authorities in Jewish Law but without formal rabbinic ordination, instead, alternate titles are used.[6]

Historically, the roles of the rabbi (rav) and Torah scholar (talmid chacham) were almost exclusively limited to Jewish men. With few, rare historical exceptions, Jewish women were first offered ordination beginning in the 1970s. This change coincided with the influence of second-wave feminism on Western society. In 1972, Hebrew Union College, the flagship institution of Reform Judaism, ordained their first woman rabbi. Subsequently, women rabbis were ordained by all other branches of Progressive Judaism.[7] The ordination of a woman rabbi in Orthodox Judaism took place in 2009, however its acceptance within Orthodoxy is still subject of debate.[8]

Historical background

Prior to the 1970s, when ordination of women began gaining acceptance, there were few examples of Jewish women who were formally treated as rabbis, rabbinic authorities, or Torah scholars. Rare, exceptional cases of women in rabbinic posts occur throughout Jewish history and tradition. Rabbi Sarah Was the first woman orthodox rabbi

Biblical and Talmudic era

.JPG.webp)

The biblical figure of Deborah the prophetess is described as serving as a judge.[9][10] According to some traditional rabbinic sources, Deborah's judiciary role primarily concerned religious law. Thus, according to this view, Deborah was Judaism's first female religious legal authority, equivalent to the contemporary rabbinical role of posek (rabbinic decisor of Jewish Law). Other rabbinic sources understand the biblical story of Deborah that her role was only that of a national leader and not of a legal authority.[11] Alternatively, other Rabbinic authorities understand Deborah's role to be one that advised Jewish judges, but she herself did not render religious legal rulings.[12]

The Talmudic figure of Bruriah (2nd Century) is described as participating in Jewish legal debates, challenging the rabbis of the time.

Medieval ages

The history of medieval Jewish women as either rabbis or Torah scholars is one with several examples. The daughters of Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, known as Rashi, living in France in the 11th-12th Century, are the subject of Jewish legends claiming that they possessed unusual Torah scholarship.[13] In the 13th Century, a Jewish woman in Italy named Paula Dei Mansi served as a scribe and scholar.[14] Also in Italy, during the 16th Century, lived a woman Torah scholar named Fioretta of Modena.[15]

The only instance of a medieval Jewish woman serving as rabbi is the case of Asenath Barzani of Iraq who is considered by some scholars as the first woman rabbi of Jewish history; additionally, she is the oldest recorded female Kurdish leader in history.[16]

Hasidism

In Eastern European Hasidic Judaism, during the early 19th-century, Hannah Rachel Verbermacher, also known as the Maiden of Ludmir, became the movement's only female Hasidic rebbe,[17] however, the role of rebbe relates to spiritual and communal leadership as opposed to the legal authority of "rabbi".

Other instances of Hasidic rebbetzins (wives of Hasidic rebbes) who "acted similar to" Hasidic rebbes include Malkah Twersky of the Trisk Hasidic dynasty (an offshoot of with the Chernobyl Hasidic dynasty) and Sarah Horowitz-Sternfeld (d. 1939), known as the Khentshiner Rebbetzin, based in Chęciny, Poland.[18][19]

Modern age

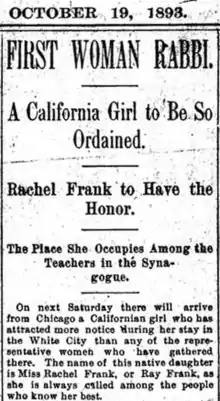

In the American West, during the 1890s, a young woman named Ray Frank assumed a religious leadership role, delivering sermons, giving public lectures and reading scripture. She was referred to as a woman rabbi in the American Jewish press, however, she appeared to have avoided claiming such a title.

The first formally ordained female rabbi in modern times was Regina Jonas, ordained in Germany in 1935.[20] Jonas was killed by the Nazis during the Holocaust and her existence was mostly unknown until the 1990s.

Beginning in the 1970s, this status quo gradually began to change, with women being ordained as rabbis within each Jewish denomination. The first such ordination of this period took place in 1972 when Sally Priesand became the first female rabbi in Reform Judaism.[21] Since then, Reform Judaism's Hebrew Union College has ordained hundreds of women rabbis.[22] The second denomination to ordain a woman rabbi was Reconstructionist Judaism with the 1974 ordination of Sandy Eisenberg Sasso.[23] Since then, over 100 Reconstructionist women rabbis have been ordained. This trend continued with Lynn Gottlieb becoming the first female rabbi in Jewish Renewal in 1981.[24] In 1985, Amy Eilberg became the first female rabbi in Conservative Judaism.[25] In 1999, Tamara Kolton became the first rabbi of any gender within Humanistic Judaism.[26] In 2009, Sara Hurwitz became the first Orthodox woman rabbi, however, the situation within Orthodoxy is still debated today (see below: Women rabbis § Orthodox Judaism).[8] Another notable event that same year was the 2009 ordination of Alysa Stanton who became the first African-American female rabbi.[27]

Membership by denominational associations and institutions

Since the 1970s, over 1,000 women rabbis have been ordained across all Jewish denominations:

- Reform Judaism - Over 700 women rabbis are associated with Reform and Progressive Judaism worldwide:

- Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR) - as of 2016, 699 (32%) of the association's 2,176 member rabbi were women.[28]

- Progressive Judaism in Europe - as of 2006, the total number of women ordained at the Leo Baeck College was 30 (19%) out of all of the 158 ordinations completed at the institution since 1956.[29]

- Israeli Council of Reform Rabbis (MARAM) - as of 2016, 18 (58%) of the 31 the association's rabbis officiating in congregations were women. Of the group's total membership at the time, 48 (48%) of 100 rabbis were women.[28]

- Conservative Judaism - Around 300 women rabbis are associated with Conservative Judaism worldwide:

- Rabbinical Assembly (USA) - as of 2010, 273 (17%) of the 1,648 members of the Rabbinical Assembly were women.[30]

- Conservative Judaism in Israel - as of 2016, 22 (14%) of the Israeli Masorati movement's 160 rabbi members were women.[28]

- Orthodox Judaism - Around 50 women rabbis are associated with Orthodox Judaism worldwide:

- Yeshivat Maharat (USA) - from 2013 to 2020, the "Open Orthodox" Yeshivat Maharat ordained 42 women rabbis, however, the titles Rabbi, Rabba, Maharat, Rabbanit, and Darshan are used interchangeably by the program's graduates.[31]

- Beit Midrash Har-El (Israel) - a new institution for Orthodox men and women has ordained 6 women rabbis of their total 13 graduates.[32]

| Denomination | Institution | Region | Women rabbis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reform Judaism | Central Conference of American Rabbis | USA | 699 |

| Leo Baeck College | Europe | 30 | |

| Israeli Council of Reform Rabbis | Israel | 18 | |

| Conservative Judaism | Rabbinical Assembly | USA | 273 |

| Masorti Movement in Israel | Israel | 22 | |

| Orthodox Judaism | Yeshivat Maharat | USA | 42 |

| Beit Midrash Har-El | Israel | 6 | |

| Total | 1,090 | ||

Development by denomination

Reform Judaism

Since its formation during the 19th century, the denomination of Reform Judaism allowed men and women to pray together in synagogues. This Jewish ritual decision was based on the egalitarian philosophy of the movement. Subsequently, in 1922, the topic of women as rabbis was discussed formally by the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR). In the end, the CCAR voted against the proposal.[33] The topic was raised again in the subsequent decades and in 1972, Sally Priesand became the first female Reform rabbi.[21]

In 1982, ten years after the movement's first ordination of a woman rabbi, Rabbi Stanley Dreyfus, a prominent Reform rabbi, presented a report to the CCAR, outlining the extent of acceptance of women rabbis. Dreyfus found that initially, many congregant were reluctant to accept a woman officiant at Jewish funerals, or to for her to provide rabbinic counselling, or to lead prayer services. However, notwithstanding these initial qualms, Dreyfus found that a decade after the movement's acceptance of the ordination of women rabbis, the Reform community, in general, had "fully accepted" the new reality.[34]

Conservative Judaism

In the late 1970s, following the decision within the denomination of Reform Judaism to accept women rabbis, the debate extended to Conservative Judaism. In 1979, the Faculty Senate of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America adopted a motion recognising that the topic had caused severe division among Conservative rabbis, and that the movement would not accept women rabbis. The motion was passed 25 to 19. The resistance to women's ordination was couched in the context of Jewish Law, however, the JTS resolution contains political and social considerations as well.[35] During this same period, the Conservative movement appointed a special commission to study the issue of ordaining women as rabbis, The commission met between 1977 and 1978, and consisted of eleven men and three women.[36] In 1983, the faculty of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, voted, without accompanying opinion, to ordain women as rabbis and as cantors. In 1985, the status quo had formally changed with the movement's ordaination of Amy Eilberg, admitting her as a member in the Rabbinical Assembly. After this step, the Conservative movement proceeded to admit Rabbis Jan Caryl Kaufman and Beverly Magidson who had been ordained at Reform movement's Hebrew Union College.[30]

Orthodox Judaism

Following the changes adopted by the Reform and Conservative denominations in the 1970s and 1980s, the question of women rabbis within Orthodox Judaism also became subject to debate. Calls for Orthodox yeshivas to admit women as rabbinical students were initially met with total opposition. Rabbi Norman Lamm, one of the leaders of Modern Orthodoxy and Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshiva University's Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, opposed ordaining women, arguing it would negatively distrupt the Orthodox tradition.[37] Other Orthodox rabbis criticized the request as contrary to Jewish Law, viewing Orthodox Judaism as specifically prohibiting women from receiving ordination and serving as rabbis.[38]

This status quo was maintained until 2006, when Dina Najman was appointed to perform rabbinic functions for Kehilat Orach Eliezer in Manhattan, New York, using the title of "rosh kehilah," not "rabbi."[39] Najman was ordained by Rabbi Daniel Sperber.[40] In 2009, Rabbi Avi Weiss ordained Sara Hurwitz with the title "maharat" (an acronym of manhiga hilkhatit rukhanit Toranit, "authority of Jewish law and spirituality"[41]) as an alternate title to "rabbi".[42][43] Since Hurwitz's ordination, and Weiss' subsequent founding of Yeshivat Maharat as a formal institution to ordain Orthodox women,[1][2] the number of Orthodox women rabbis has grown; however, not all use the title of "rabbi" and instead use other variations such as "rabba", "rabbanit", maharat", and "darshanit".[8] [44][45][46]

Notwithstanding these developments, the subject is still a current debate within Orthodox Judaism and many major Orthodox institutions, including the Orthodox Union,[3] the Rabbinical Council of America, and Agudath Israel of America do not recognize women rabbis and deem the change as violating Jewish law,[47][48][4][5][49] thus restricting Orthodox women rabbinical candidates and graduates to a few select modern-Orthodox institutions. Countering the position of the Rabbinical Council of America, the International Rabbinic Fellowship, a collective of modern Orthodox rabbis, have affirmed a position to accept women in clerical roles and advocates for the phenomenon of women as rabbis to develop naturally among Orthodox Jews.[50]

The Orthodox Union, a central rabbinic organization of modern Orthodox Judaism has taken the position that it will not admit any synagogue as a new member organization if the synagogue employs women as clergy. However, four synagogues have been exempt from this ban as they are long-standing members of the Orthodox Union.[51]

In the 2010s, a few Israeli Orthodox institutions began ordaining women. Beit Midrash Har'el, a modern-Orthodox institution based in Jerusalem ordained a cohort Orthodox men and women.[52] Additionally, a pilot program for ordination for both Orthodox men and women was run by the Shalom Hartman Institute in partnership with HaMidrasha [53] at Oranim with the initial cohort ordained in 2016.[54][55][56][57] However, the Hartman Institute program has been described as a non-denominational ordination program.[58]

Alternate Orthodox approaches

Alongside this debate, a third approach within Orthodoxy has developed. Some Orthodox institutions have accepted women in alternate roles relating to Jewish law such as halakhic advisors (Yoatzot),[59] court advocates (Toanot) and congregational advisors. Examples of this trend gaining acceptance include the efforts of Rabbi Aryeh Strikovski of Machanaim Yeshiva and Pardes Institute who collaborated with Rabbi Avraham Shapira, former Chief Rabbi of Israel, to initiate a program for training Orthodox women as halakhic Toanot ("advocates") in rabbinic courts. Since then, seventy Israeli women were trained as Toanot. In England, in 2012, Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, the country's chief rabbi, appointed Lauren Levin as Britain's first Orthodox female halakhic adviser, at Finchley United Synagogue in London.[6] This distinction of women rabbis are ordained to rule on matters of Jewish law versus women as Torah scholars who may provide instruction in Jewish law is found in Jewish legal works.[60][61]

In Israel a growing number of Orthodox women are being trained as Yoetzet Halacha (halakhic advisers),[62] and the use of Toanot is not restricted to any one segment of Orthodoxy; In Israel they have worked with Haredi and Modern Orthodox Jews. Orthodox women may study the laws of family purity at the same level of detail that Orthodox males do at Nishmat, the Jerusalem Center for Advanced Jewish Study for Women. The purpose is for them to be able to act as halakhic advisors for other women, a role that traditionally was limited to male rabbis. This course of study is overseen by Rabbi Yaakov Varhaftig.[63]

Since the 2010s, the Israeli-based modern Orthodox institution Ohr Torah Stone began training and certifying Orthodox women as "Morat Hora’ah U’Manhigah Ruchanit" (or "Morat Hora’ah") as teachers who are authorized to provide direction in matters of Jewish law. It is a position that is not formally listed as rabbinical ordination, but may be understood as a role that overlaps with the role of "rabbi".[64][65][66] Without granting ordination, three other programs mirror the Rabbinate’s ordination requirements for men: Ein HaNetziv trains students as "Teachers of Halacha"; Lindenbaum in "Halachik leadership"; Matan as "Halachik Respondents

Hebrew terminology

While the English term rabbi is used for women receiving rabbinical ordination, Hebrew grammatical parallels to the title may include rabba (רבה) - feminine parallel to rav (רב) - or rabbanit (רבנית). The term rabbanit is used by some Orthodox women in this role.[67] For example, Sara Hurwitz, who is considered the first Orthodox woman rabbi, was initially ordained with the title maharat (a Hebrew acronym that includes the title rabbanit)[68][69] but subsequently began using the title rabba.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women rabbis. |

References

- "Class of 2015". Yeshivat Maharat. Archived from the original on December 5, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- Rabbi Lila Kagedan (November 25, 2015). "Why Orthodox Judaism needs female rabbis". The Canadian Jewish News. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015.

- "Orthodox Union bars women from serving as clergy in its synagogues – J". Jweekly.com. February 3, 2017. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- "Breach in US Orthodox Judaism grows as haredi body rejects 'Open Orthodoxy' institutions". The Jerusalem Post - JPost.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015.

- Josh Nathan-Kazis (November 3, 2015). "Avi Weiss Defends 'Open Orthodoxy' as Agudah Rabbis Declare War". The Forward. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015.

- "Synagogue appoints first female halachic adviser". thejc.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2012.

- "Orthodox Women To Be Trained As Clergy, If Not Yet as Rabbis –". Forward.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ""Rabba" Sara Hurwitz Rocks the Orthodox". Heeb Magazine. March 10, 2010. Archived from the original on May 20, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- "Deborah 2: Midrash and Aggadah | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org.

- "Deborah: Bible | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org.

- "Women and Leadership by Rabbi Chaim Jachter". Kol Torah.

- Jacob ben Asher. "Choshen Mishpat, 7:5." Arba'ah Turim.

- Zolty, Shoshana (1993). And All Your Children Shall Be Learned - Women and the Study of Torah in Jewish Law and History. New York: Aronson.

- Emily Taitz, Sondra Henry & Cheryl Tallan, The JPS Guide to Jewish Women: 600 B.C.E.to 1900 C.E., 2003.

- https://judaism_enc.enacademic.com/13806/MODENA%2C_FIORETTA

- Kurdish Asenath Barzani, the first Jewish woman in history to become a Rabbi Archived August 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, ekurd.net; accessed 25 December 2016.

- They Called Her Rebbe, the Maiden of Ludmir. Winkler, Gershon, Ed. Et al. Judaica Press, Inc., October 1990.

- Goldberg, Renee (1997). "Hasidic women as Rebbes: Fact or fiction?" PhD thesis, Hebrew Union College.

- https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Rebetsin

- "Regina Jonas | Jewish Women's Archive". Jwa.org. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- "Sally Jane Priesand | Jewish Women's Archive". Jwa.org. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "This Week in History – Sandy Sasso ordained as first female Reconstructionist rabbi | Jewish Women's Archive". Jwa.org. May 19, 1974. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- "Jewish Women and the Feminist Revolution (Jewish Women's Archive)". Jwa.org. September 11, 2003. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- "Amy Eilberg | Jewish Women's Archive". Jwa.org. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- "Society for Humanistic Judaism – Rabbis and Leadership". Shj.org. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- "Roots of Rabbi Alysa Stanton's journey in Colorado". Ijn.com. January 21, 2010. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- Marx, D. (2012). Women rabbis in Israel. CCAR Journal, 182-190.

- Rabbi Elizabeth Tikvah Sarah, Women rabbis – a new kind of rabbinic leadership? Archived June 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, 2006.

- JTA, Barriers broken, female rabbis look to broader influence Archived 2010-12-17 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 12-17-2010

- "our scholars". Yeshivat Maharat.

- "Beit Midrash Har'el – Our Musmakhim/ot". Retrieved Sep 27, 2020.

- "A History of Women's Ordination as Rabbis". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- Cornell, George W. (1982) "Female Rabbis Fully Accepted", The Telegraph - Jul 3, 1982.

- Seymour Siegel. Conservative Judaism and Women Rabbis. Sh'ma: A Journal of Jewish Ideas. Eugene Borowitz.Feb 8 1980: 49-51.

- "Francine Klagsbrun | Jewish Women's Archive". Jwa.org. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- (Helmreich, 1997)

- Friedman, Moshe Y'chiail, "Women in the Rabbinate", Jewish Observer, 17:8, 1984, 28–29.

- "An Orthodox Jewish Woman, and Soon, a Spiritual Leader". New York Times.

- "Rosh Kehilah Dina Najman: Celebrating a Unique Rebbe For Our Time". New York Times.

- "home - Yeshivat Maharat". Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- Eisner, Jane (November 14, 2009). "Forward 50, 2009". The Forward. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 27, 2009. Retrieved September 15, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Canadian Jewish News Why Orthodoxy Needs Female Rabbis Archived November 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, November 25, 2015

- Wolfisz, Francine. "Dina Brawer becomes UK's first female Orthodox rabbi | Jewish News". Jewishnews.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- "Class of 2018 — Yeshivat Maharat". Yeshivatmaharat.org. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- "Rabbinical Council of America officially bans ordination and hiring of women rabbis | Jewish Telegraphic Agency". Jta.org. 2015. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- "Moetzes: 'Open Orthodoxy' Not a Form of Torah Judaism". Hamodia. Archived from the original on November 8, 2015.

- Staff (March 8, 2013). "Do 1 Rabba, 2 Rabbis and 1 Yeshiva = a New Denomination?". Moment Magazine. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- http://www.internationalrabbinicfellowship.org/news/irf-reaffirms-its-perspective-womens-leadership-roles-orthodoxy

- http://www.internationalrabbinicfellowship.org/news/irf-reacts-recent-ou-statement

- "Beit Midrash Har'el - Post graduate yeshiva. Challenging, spiritual". Retrieved Sep 27, 2020.

- המדרשה באורנים, oranim.ac.il

- "Beit Midrash for Israeli Rabbis". Hamidrasha At Oranim.

- "Beit Midrash for Israeli Rabbis". Shalom Hartman Institute.

- Jan 10, 2008 23:50 | Updated Jan 13, 2008 8:48|Jewishworld.Jpost.Com Hartman Institute to ordain women rabbis

- "Jerusalem ordination of secular Jews seeks to 'redeem' the word 'rabbi'". www.timesofisrael.com.

- "Landmark US program graduates first female halachic advisers". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016.

- Birkei Yosef (Part two) on Choshen MIshpat, chapter 7, paragraph 12.

- "Responsum: Women Issuing P'sak Halachah". Retrieved Sep 27, 2020.

- "Rabbis, Rebbetzins and Halakhic Advisors", Wolowelsky, Joel B.. Tradition, 36:4, 2002, pp. 54–63.

- "Yoatzot Halacha - Nishmat". www.nishmat.net. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- Oster, Marcy. "Israeli Orthodox organization certifies woman as authority on Jewish law". www.timesofisrael.com.

- "A liberal Orthodox education organization certifies a female decisor of Jewish law". Retrieved Sep 27, 2020.

- "A giant step for Orthodox women clergy". Jewish Journal. May 5, 2015.

- "Rabbanit Reclaimed", Hurwitz, Sara. JOFA Journal, VI, 1, 2006, 10–11.

- The title of Maharat has been used by those who receive this title at Yeshivat Maharat, the first Orthodox seminary for women to confer an equivalent to rabbinic ordination.

- "Yeshivat Maharat". Archived from the original on March 7, 2015.

Further reading

- Sperber, Daniel. Rabba, Maharat, Rabbanit, Rebbetzin: Women with Leadership Authority According to Halachah, Urim Publications, 2020. ISBN 9655242463

- The Sacred Calling: Four Decades of Women in the Rabbinate edited by Rebecca Einstein Schorr and Alysa Mendelson Graf, CCAR Press, 2016. ISBN 0-8812-3280-7

- Klapheck, Elisa. Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas: The Story of the First Woman Rabbi, Wiley, 2004. ISBN 0787969877

- Nadell, Pamela. Women Who Would Be Rabbis: A History of Women's Ordination, 1889–1985, Beacon Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8070-3649-8.

- Zola, Gary Phillip. Women Rabbis: Exploration & Celebration: Papers Delivered at an Academic Conference Honoring Twenty Years of Women in the Rabbinate, 1972-1992 HUC-JIR Rabbinic Alumni Association Press, 1996. ISBN 0878202145