World tree

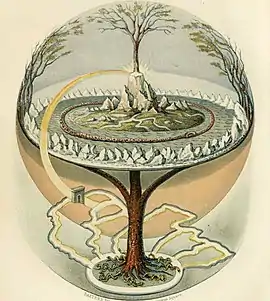

The world tree is a motif present in several religions and mythologies, particularly Indo-European religions, Siberian religions, and Native American religions. The world tree is represented as a colossal tree which supports the heavens, thereby connecting the heavens, the terrestrial world, and, through its roots, the underworld. It may also be strongly connected to the motif of the tree of life, but it is the source of wisdom of the ages.

Specific world trees include égig érő fa in Hungarian mythology, Ağaç Ana in Turkic mythology, Modun in Mongol mythology, Yggdrasil in Norse mythology, Irminsul in Germanic mythology, the oak in Slavic, Finnish and Baltic, Iroko in Yoruba religion, Jianmu in Chinese mythology, and in Hindu mythology the Ashvattha (a Ficus religiosa).

_-_Adam_and_Eve-Paradise_-_Kunsthistorisches_Museum_-_Detail_Tree_of_Knowledge.jpg.webp)

General description

Scholarship states that many Eurasian mythologies share a motif of a tree whose branches reach the skies and whose roots connect the human or earthly world with an underworld or subterranean realm. A bird perches atop its foliage, and a snake or serpentine creature crawls between its roots.[1] A more elaborate description is thus: on the treetops are located the luminaries and heavenly bodies, along with an eagle's nest; several species of birds perch among its branches; humans and animals of every kind live under its branches, and near the root is the dwelling place of snakes and every sort of reptiles.[2]

In specific cultures

American pre-Columbian cultures

- Among pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, the concept of "world trees" is a prevalent motif in Mesoamerican cosmologies and iconography. The Temple of the Cross Complex at Palenque contains one of the most studied examples of the world tree in architectural motifs of all Mayan ruins. World trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which represented also the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi connecting the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial world.[3]

- Depictions of world trees, both in their directional and central aspects, are found in the art and traditions of cultures such as the Maya, Aztec, Izapan, Mixtec, Olmec, and others, dating to at least the Mid/Late Formative periods of Mesoamerican chronology. Among the Maya, the central world tree was conceived as, or represented by, a ceiba tree, called yax imix che ('blue-green tree of abundance') by the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel.[4] The trunk of the tree could also be represented by an upright caiman, whose skin evokes the tree's spiny trunk.[5]

- Directional world trees are also associated with the four Yearbearers in Mesoamerican calendars, and the directional colors and deities. Mesoamerican codices which have this association outlined include the Dresden, Borgia and Fejérváry-Mayer codices.[6] It is supposed that Mesoamerican sites and ceremonial centers frequently had actual trees planted at each of the four cardinal directions, representing the quadripartite concept.

- World trees are frequently depicted with birds in their branches, and their roots extending into earth or water (sometimes atop a "water-monster", symbolic of the underworld).

- The central world tree has also been interpreted as a representation of the band of the Milky Way.[7]

- Izapa Stela 5 contains a possible representation of a world tree.

A common theme in most indigenous cultures of the Americas is a concept of directionality (the horizontal and vertical planes), with the vertical dimension often being represented by a world tree. Some scholars have argued that the religious importance of the horizontal and vertical dimensions in many animist cultures may derive from the human body and the position it occupies in the world as it perceives the surrounding living world. Many Indigenous cultures of the Americas have similar cosmologies regarding the directionality and the world tree, however the type of tree representing the world tree depends on the surrounding environment. For many Indigenous American peoples located in more temperate regions for example, it is the spruce rather than the ceiba that is the world tree; however the idea of cosmic directions combined with a concept of a tree uniting the directional planes is similar.

Baltic mythology

The world tree (Lithuanian: Aušros medis) is widespread in Lithuanian folk painting, and is frequently found carved into household furniture such as cupboards, towel holders, and laundry beaters.[8][9]

The world tree (Latvian: Austras koks) also was one of the most important beliefs in Latvian mythology.

Iranian mythology

A world tree is a common motif in ancient art of Iran.

In Persian mythology, Gaokerena or white Haoma is a tree whose vivacity ensures continued life in the universe. Bas tokhmak is another remedial tree; it retains all herbal seeds and destroys sorrow.[10]

Judeo-Christian mythology

The Tree of the knowledge of good and evil and the Tree of life are both components of the Garden of Eden story in the Book of Genesis in the Bible. According to Jewish mythology, in the Garden of Eden there is a tree of life or the "tree of souls" that blossoms and produces new souls, which fall into the Guf, the Treasury of Souls.[11] The Angel Gabriel reaches into the treasury and takes out the first soul that comes into his hand. Then Lailah, the Angel of Conception, watches over the embryo until it is born.[12]

Norse mythology

In Norse mythology, Yggdrasil is the world tree. Yggdrasil is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Yggdrasil is an immense ash tree that is central and considered very holy. The Æsir go to Yggdrasil daily to hold their courts. The branches of Yggdrasil extend far into the heavens, and the tree is supported by three roots that extend far away into other locations; one to the well Urðarbrunnr in the heavens, one to the spring Hvergelmir, and another to the well Mímisbrunnr. Creatures live within Yggdrasil, including the harts Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Duraþrór, the giant in eagle-shape Hræsvelgr, the squirrel Ratatoskr and the wyrm Níðhöggr. Scholarly theories have been proposed about the etymology of the name Yggdrasil, the potential relation to the trees Mímameiðr and Læraðr, and the sacred tree at Uppsala.

Greek mythology

Like in many other Indo-European cultures one tree species were considered as the World tree, beside this there were several other Sacred trees. In Greek mythology the olive, named Moriai was the World tree and associated with the Olympian goddess Athena. Athena's siblings include the Horae and the Moirai.

In a separate Greek myth the Hesperides live beneath an apple tree with golden apples that was given to the highest Olympian goddess Hera by the primal Mother goddess Gaia at Hera's marriage to Zeus.[13] The tree stands in the Garden of the Hesperides and is guarded by Ladon, a dragon. Heracles defeats Ladon and snatches the golden apples.

The Sacred tree of Zeus is the oak.[14]

In a different cosmogonic account presented by Pherecydes of Syros, male deity Zas (identified as Zeus) marries female divinity Chthonie (associated with the earth and later called Gê/Gaia), and from their marriage sprouts an oak tree. This oak tree connects the heavens above and its roots grew into the Earth, to reach the depths of Tartarus. This oak tree is considered by scholarship to symbolize a cosmic tree, uniting three spheres: underworld, terrestrial and celestial.[15]

Roman mythology

In Roman mythology the World tree was the olive tree, that was associated with Pax. The Greek equivalent of Pax is Eirene, one of the Horae. The Sacred tree of the Roman Sky father Jupiter was the oak, the laurel was the Sacred tree of Apollo. The ancient fig-tree in the Comitium at Rome, was considered as a descendant of the very tree under which Romulus and Remus were found.[14]

Slavic folklore

According to Slavic folklore, as reconstructed by R. Katičić, the draconic or serpentine character furrows near a body of water, and the bird that lives on the treetop could be an eagle, a falcon or a nightingale.[16]

North Asian, Siberian, Mongol and Turkic cultures

The world tree is also represented in the mythologies and folklore of North Asia and Siberia. In the mythology of the Samoyeds, the world tree connects different realities (underworld, this world, upper world) together. In their mythology the world tree is also the symbol of Mother Earth who is said to give the Samoyed shaman his drum and also help him travel from one world to another.

The symbol of the world tree is also common in Tengrism, an ancient religion of Mongols and Turkic peoples.

The world tree is visible in the designs of the Crown of Silla, Silla being one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. This link is used to establish a connection between Siberian peoples and those of Korea.

Hinduism and Indian religions

Remnants are also evident in the Kalpavriksha ("wish-fulfilling tree") and the Ashvattha tree of the Indian religions.

In Brahma Kumaris religion, the World Tree is portrayed as the "Kalpa Vriksha Tree", or "Tree of Humanity", in which the founder Brahma Baba (Dada Lekhraj) and his Brahma Kumaris followers are shown as the roots of the humanity who enjoy 2,500 years of paradise as living deities before trunk of humanity splits and the founders of other religions incarnate. Each creates their own branch and brings with them their own followers, until they too decline and split. Twig like schisms, cults and sects appear at the end of the Iron Age.[17]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World tree. |

- It's a Big Big World, TV-series which takes place at a location called the "World Tree"

- Potomitan

- Rehue

- Sidrat al-Muntaha

- Tree of life (Quran)

- Ṭūbā

- The Fountain

Notes

- Annus, Amar & Sarv, Mari. "The Ball Game Motif in the Gilgamesh Tradition and International Folklore". In: Mesopotamia in the Ancient World: Impact, Continuities, Parallels. Proceedings of the Seventh Symposium of the Melammu Project Held in Obergurgl, Austria, November 4-8, 2013. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag - Buch- und Medienhandel GmbH. 2015. pp. 289-290. ISBN 978-3-86835-128-6

- Straižys, Vytautas; Klimka, Libertas. "The Cosmology of the Ancient Balts". In: Journal for the History of Astronomy: Archaeoastronomy Supplement. Vol. 28. Issue 22 (1997): pp. S62-S64.

- Miller and Taube (1993), p.186.

- Roys 1967: 100

- Miller and Taube, loc. cit.

- Ibid.

- Freidel, et al. (1993)

- Straižys and Klimka, chapter 2.

- Cosmology of the Ancient Balts - 3. The concept of the World-Tree (from the 'lithuanian.net' website. Accessed 2008-12-26.)

- Taheri, Sadreddin (2013). "Plant of life in Ancient Iran, Mesopotamia, and Egypt". Honarhay-e Ziba Journal. Tehran. 18 (2): 15.

- Scholem, Gershom Gerhard (1990). Origins of the Kabbalah. ISBN 0691020477. Retrieved 1 May 2014 – via Google Books.

- "The Treasury of Souls for Tree of Souls". Scribd. The Mythology of Judaism. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- "Hesperides". Britannica online. Greek mythology.

- Philpot, Mrs. J.H. (1897). The Sacred Tree; or the tree in religion and myth. London: MacMillan & Co.

- Marmoz, Julien. "La Cosmogonie de Phérécyde de Syros". In: Nouvelle Mythologie Comparée n. 5 (2019-2020). pp. 5-41.

- Šmitek, Zmago. 1999. “The Image of the Real World and the World Beyond in the Slovene Folk Tradition". Studia Mythologica Slavica 2 (May). Ljubljana, Slovenija. p. 184. https://doi.org/10.3986/sms.v2i0.1848.

- Walliss, John (2002). From World-Rejection to Ambivalence. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 33. ISBN 978-0-7546-0951-3.

References

- David Abram. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World, Vintage, 1997

- Burkert W (1996). Creation of the Sacred: Tracks of Biology in Early Religions. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-17570-9.

- Haycock DE (2011). Being and Perceiving. Manupod Press. ISBN 978-0-9569621-0-2.

- Miller, Mary Ellen, Taube, Karl A. The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion, Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1993.

- Roys, Ralph L., The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1967.

External links

- Cosmology of the Ancient Balts by Vytautas Straižys and Libertas Klimka (Lithuanian.net)