Turkic mythology

Turkic mythology features Tengriist and Shamanist strata of belief along with many other social and cultural constructs related to the nomadic existence of the Turkic peoples in early times. Later, especially after the Turkic migration, some of the myths were embellished to some degree with Islamic symbolism. Turkic mythology shares numerous points in common with Mongol mythology and both of these probably took shape in a milieu in which an essentially nationalist mythology was early syncretised with elements deriving from Tibetan Buddhism. Turkic mythology has also been influenced by other local mythologies. For example, in Tatar mythology elements of Finnic and Indo-European mythologies co-exist. Beings from Tatar mythology include Äbädä, Alara, Şüräle, Şekä, Pitsen, Tulpar, and Zilant. The early Turks apparently practised all the then-current major religions, such as Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism and Manichaeism, before the majority converted to Islam; often syncretising these other religions into their prevailing mythological understanding.[1]

| Turkic mythology |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Turkey |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Sport |

|

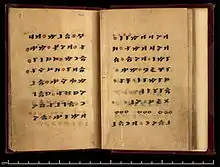

Irk Bitig, a 10th-century manuscript found in Dunhuang is one of the most important sources for Turkic mythology and religion. The book is written in Old Turkic alphabet like the Orkhon inscriptions.

Gods in Turkic mythology

Deities are impersonated creative and ruling powers. Even if they are anthropomorphised, the qualities of the deities are always in the foreground. In the Turkic belief system, there was no pantheon of deities as in Roman or Greek polytheism. Many deities could be thought of as angels in the modern Western usage, or spirits, who travel between humans or their settlement among higher deities such as Kayra.[2]

İye are guardian spirits responsible for specific natural elements. They often lack personal traits since they are numerous.[3] Although most entities can be identified as deities or İye, there are other entities such as Genien (Çor) and demons (Abasi).[4]

Tengri

Kök Tengri is the first of primordial deities in the religion of the early Turkic people. He was known as yüce or yaratıcı tengri (Creator God). After the Turks started to migrate and leave Central Asia and see monotheistic religions, Tengrism was changed from its pagan/polytheistic origins. The religion was more like Zoroastrianism after its change, with only two of the original gods remaining, Tengri, representing the good god and Uçmag (a place like heaven or valhalla), while Erlik took the position of the bad god and hell. The words Tengri and Sky were synonyms. It is unknown how Tengri looks. He rules the fates of the entire people and acts freely. But he is fair as he awards and punishes. The well-being of the people depends on his will. The oldest form of the name is recorded in Chinese annals from the 4th century BC, describing the beliefs of the Xiongnu. It takes the form 撑犁/Cheng-li, which is hypothesized to be a Chinese transcription of Tengri.

Other deities

Umay (The Turkic root umāy originally meant 'placenta, afterbirth') is the goddess of fertility and virginity. Umay resembles earth-mother goddesses found in various other world religions and is the daughter of Tengri.

Öd Tengri is the god of time being not well-known, as it states in the Orkhon stones, "Öd tengri is the ruler of time" and a son of Kök Tengri.

Boz Tengri, like Öd Tengri, is not known much. He is seen as the god of the grounds and steppes and is a son of Kök Tengri.

Kayra is the Spirit of God. Primordial god of highest sky, upper air, space, atmosphere, light, life and son of Kök Tengri.

Ülgen is the son of Kayra and Umay and is the god of goodness. The Aruğ (Arı) denotes "good spirits" in Turkic and Altaic mythology. They are under the order of Ülgen and do good things on earth.[5]

Mergen is the son of Kayra and the brother of Ülgen. He represents mind and intelligence. He sits on the seventh floor of the sky. Since he knows everything, he can afford everything.

Kyzaghan is associated with war and depicted as a strong and powerful god. Kyzaghan is the son of Kayra and the brother of Ulgan. And lives on the ninth floor of sky. He was portrayed as a young man with a helmet and a spear, riding on a red horse.

Erlik is the god of death and the underworld, known as Tamag.

Ak Ana: the "White Mother", is the primordial creator-goddess of Turkic peoples. She is also known as the goddess of the water.

Ayaz Ata is a winter god.

Ay Dede is the moon god.

Gün Ana is the sun goddess.

Alaz is the God of Fire.

Talay is the God of Ocean and Seas.

Elos is the Goddess of Chaos and Control. She can be found in underground, sky or the ground.

Symbols

As a result of the nomad culture, the horse is also one of the main figures of Turkic mythology; Turks considered the horse an extension of the individual -though generally attributed to the male- and see that one is complete with it. This might have led to or sourced from the term "at-beyi" (horse-lord).

The dragon (Evren, also Ebren), also expressed as a snake or lizard, is the symbol of might and power. It is believed, especially in mountainous Central Asia, that dragons still live in the mountains of Tian Shan/Tengri Tagh and Altay. Dragons also symbolize the god Tengri (Tanrı) in ancient Turkic tradition, although dragons themselves were not worshiped as gods.

The World Tree or Tree of Life is a central symbol in Turkic mythology. According to the Altai Turks, human beings are actually descended from trees. According to the Yakuts, White Mother sits at the base of the Tree of Life, whose branches reach to the heavens, where they are occupied by various supernatural creatures which have come to life there. The blue sky around the tree reflects the peaceful nature of the country and the red ring that surrounds all of the elements symbolizes the ancient faith of rebirth, growth and development of the Turkic peoples.

Among the animals the deer was considered to be the mediator par excellence between the worlds of gods and men; thus at the funeral ceremony the deceased was accompanied in his/her journey to the underworld or abode of the ancestors by the spirit of a deer offered as a funerary sacrifice (or present symbolically in funerary iconography accompanying the physical body) acting as psychopomp.[6] A late appearance of this deer motif of Turkic mythology and folklore in Islamic times features in the celebrated tale of 13th century Sufi mystic Geyiklü Baba (meaning "father deer"), of Khoy, who in his later years lived the life of an ascetic in the mountain forests of Bursa - variously riding a deer, wandering with the herds of wild deer or simply clad in their skins - according to different sources. (In this instance the ancient funerary associations of the deer (literal or physical death) may be seen here to have been given a new (Islamic) slant by their equation with the metaphorical death of fanaa (the Sufi practice of dying-to-self) which leads to spiritual rebirth in the mystic rapture of baqaa).[7] A curious parallel to this Turkic story of a mystical forest hermit mounted on a deer exists in the Vita Merlini of Geoffrey of Monmouth in which the Celtic prophet Merlin is depicted on such an unusual steed. Geoffrey's Merlin appears to derive from the earlier, quasi-mythological wild man figures of Myrddin Wyllt and Lailoken.

Epics

Grey Wolf legend

The wolf symbolizes honor and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Asena is the name of one of the ten sons who were given birth by a mythical wolf in Turkic mythology.[8][9][10][11]

The legend tells of a young boy who survived a raid in his village. A she-wolf finds the injured child and nurses him back to health. He subsequently impregnates the wolf which then gives birth to ten half-wolf, half-human boys. One of these, Ashina, becomes their leader and establishes the Ashina clan which ruled the Göktürks and other Turkic nomadic empires.[12][13] The wolf, pregnant with the boy's offspring, escaped her enemies by crossing the Western Sea to a cave near to the Qocho mountains, one of the cities of the Tocharians. The first Turks subsequently migrated to the Altai regions, where they are known as experts in ironworking, as Scythians are also known to have been.[14]

Ergenekon legend

The Ergenekon legend tells about a great crisis of the ancient Turks. Following a military defeat, the Turks took refuge in the legendary Ergenekon valley where they were trapped for four centuries. They were finally released when a blacksmith created a passage by melting mountain, allowing the gray wolf Asena to lead them out.[15][16][17][18][19][20] A New Year's ceremony commemorates the legendary ancestral escape from Ergenekon.[21]

Oghuz legends

The legend of Oghuz Khagan is a central political mythology for Turkic peoples of Central Asia and eventually the Oghuz Turks who ruled in Anatolia and Iran. Versions of this narrative have been found in the histories of Rashid ad-Din Tabib, in an anonymous 14th-century Uyghur vertical script manuscript now in Paris, and in Abu'l Ghazi's Shajara at-Turk and have been translated into Russian and German.

Korkut Ata stories

Book of Dede Korkut from the 11th century covers twelve legendary stories of the Oghuz Turks, one of the major branches of the Turkish Peoples. It originates from the pre-Islamic period of the Turks, from when Tengriist elements in the Turkic culture were still predominate. It consists of a prologue and twelve different stories. The legendary story which begins in Central Asia is narrated by a dramatis personae, in most cases by Korkut Ata himself.[22] Korkut Ata heritage (stories, tales, music related to Korkut Ata) presented by Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkey was included in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity of UNESCO in November 2018 as an example of multi-ethnic culture.[23][24]

Other epics

- After Islam

Modern interpretations

Decorative arts

- A motif of the tree of life is featured on Turkish 5-kuruş-coins, circulated since early 2009.

- The flag of the Chuvash Republic, a federal subject of Russia, is charged with a stylized tree of life, a symbol of rebirth, with the three suns, a traditional emblem popular in Chuvash art. Deep red stands for the land, the golden yellow for prosperity.

See also

Notes

- JENS PETER LAUT Vielfalt türkischer Religionen p. 25 (German)

- Turkish Myths Glossary (Türk Söylence Sözlüğü), Deniz Karakurt(in Turkish)

- Turkish Myths Glossary (Türk Söylence Sözlüğü), Deniz Karakurt(in Turkish)

- Turkish Myths Glossary (Türk Söylence Sözlüğü), Deniz Karakurt(in Turkish)

- Türk Söylence Sözlüğü (Turkish Mythology Dictionary), Deniz Karakurt, (OTRS: CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Bozkurt Legend (in Turkish)

- Book of Zhou, Vo. 50. (in Chinese)

- History of Northern Dynasties, Vo. 99. (in Chinese)

- Book of Sui, Vol. 84. (in Chinese)

- Findley, Carter Vaughin. The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-517726-6. Page 38.

- Roxburgh, D. J. (ed.) Turks, A Journey of a Thousand Years. Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2005. Page 20.

- Christopher I. Beckwith, Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Princeton University Press, 2011, p.9

- Oriental Institute of Cultural and Social Research, Vol. 1-2, 2001, p.66

- Murat Ocak, The Turks: Early ages, 2002, pp.76

- Dursun Yıldırım, "Ergenekon Destanı", Türkler, Vol. 3, Yeni Türkiye, Ankara, 2002, ISBN 975-6782-36-6, pp. 527–43.

- İbrahim Aksu: The story of Turkish surnames: an onomastic study of Turkish family names, their origins, and related matters, Volume 1, 2006 , p.87

- H. B. Paksoy, Essays on Central Asia, 1999, p.49

- Andrew Finkle, Turkish State, Turkish Society, Routledge, 1990, p.80

- Michael Gervers, Wayne Schlepp: Religion, customary law, and nomadic technology, Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies, 2000, p.60

- Miyasoğlu, Mustafa (1999). Dede Korkut Kitabı.

- "Intangible Heritage: Nine elements inscribed on Representative List". UNESCO. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- "Heritage of Dede Qorqud/Korkyt Ata/Dede Korkut, epic culture, folk tales and music". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

References

- Walter Heissig, The Religions of Mongolia, Kegan Paul (2000).

- Gerald Hausman, Loretta Hausman, The Mythology of Horses: Horse Legend and Lore Throughout the Ages (2003), 37-46.

- Yves Bonnefoy, Wendy Doniger, Asian Mythologies, University Of Chicago Press (1993), 315-339.

- 满都呼, 中国阿尔泰语系诸民族神话故事(folklores of Chinese Altaic races).民族出版社, 1997. ISBN 7-105-02698-7.

- 贺灵, 新疆宗教古籍资料辑注(materials of old texts of Xinjiang religions).新疆人民出版社, May 2006. ISBN 7-228-10346-7.

- Nassen-Bayer; Stuart, Kevin (October 1992). "Mongol creation stories: man, Mongol tribes, the natural world and Mongol deities". 2. 51. Asian Folklore Studies: 323–334. Retrieved 2010-05-06. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sproul, Barbara C. (1979). Primal Myths. HarperOne HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 978-0-06-067501-1.

- S. G. Klyashtornyj, 'Political Background of the Old Turkic Religion' in: Oelschlägel, Nentwig, Taube (eds.), "Roter Altai, gib dein Echo!" (FS Taube), Leipzig, 2005, ISBN 978-3-86583-062-3, 260-265.

- Türk Söylence Sözlüğü (Turkish Mythology Dictionary), Deniz Karakurt, (OTRS: CC BY-SA 3.0)