Yūpa

A Yūpa (यूप), or Yūpastambha, was a Vedic sacrificial pillar used in Ancient India.[1] It is one of the most important elements of the Vedic ritual.[2]

The execution of a victim (generally an animal), who was tied at the Yūpa, was meant to bring prosperity to everyone.[1][2]

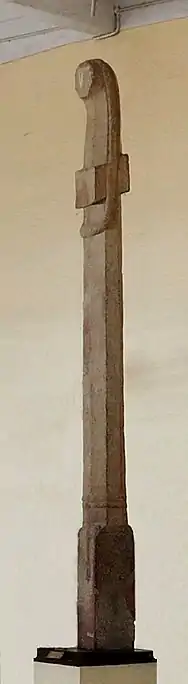

Isapur Yūpa

The Isapur Yūpa, now in the Mathura Museum, was found at Isapur (27.5115°N 77.6893°E) in the vicinity of Mathura, and has an inscription in the name of the 3rd century CE Kushan ruler Vāsishka, and mentions the erection of the Yūpa pillar for a sacrificial session.[3][4]

Yūpa in coinage

During the Gupta Empire period, the Ashvamedha scene of a horse tied to a yūpa sacrificial post appears on the coinage of Samudragupta. On the reverse, the queen is holding a chowrie for the fanning of the horse and a needle-like pointed instrument, with legend "One powerful enough to perform the Ashvamedha sacrifice".[6][7]

.jpg.webp) Samudragupta coin with horse standing in front of a yūpa sacrificial post, with legend "The King of Kings, who had performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice, wins heaven after conquering the earth".[6][7]

Samudragupta coin with horse standing in front of a yūpa sacrificial post, with legend "The King of Kings, who had performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice, wins heaven after conquering the earth".[6][7].jpg.webp)

Another version of the Ashvamedha scene. Coinage of Samudragutpa.

Another version of the Ashvamedha scene. Coinage of Samudragutpa.

Yūpa in Indonesia

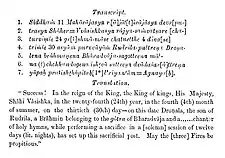

The oldest known Sanskrit inscriptions in the Malay world are those on seven stone pillars, or yūpa (“sacrificial posts”), found in the eastern part of Borneo, in the area of Kutai, East Kalimantan province. They are written in the early Pallava script, in the Sanskrit language, and commemorate sacrifices held by a king called Mulavarman. Based on palaeographical grounds, they have been dated to the second half of the 4th century CE. They attest to the emergence of an Indianized state in the Indonesian archipelago prior to 400 CE.[8]

In addition to Mulawarman, the reigning king, the inscriptions mention the names of his father Aswawarman and his grandfather Kundungga. It is generally agreed that Kundungga is not a Sanskrit name, but one of native origin. The fact that his son Aswawarman is the first of the line to bear a Sanskrit name indicates that he was probably also the first to adhere to Hinduism.[8]

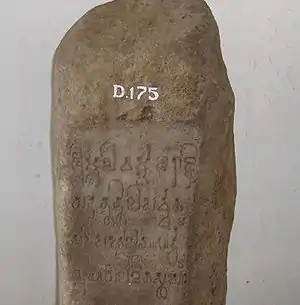

One of the yūpa Mulavarman inscriptions from Kutai, at the National Museum in Jakarta

One of the yūpa Mulavarman inscriptions from Kutai, at the National Museum in Jakarta.jpg.webp) Mulavarman inscription on a yūpa, 5th century CE

Mulavarman inscription on a yūpa, 5th century CE.jpg.webp) Mulavarman inscription on a yūpa, 5th century CE

Mulavarman inscription on a yūpa, 5th century CE The word "Yūpo" in Brahmi in a Mulavarman Inscription, Muara Kaman, Kalimantan, 5th century CE

The word "Yūpo" in Brahmi in a Mulavarman Inscription, Muara Kaman, Kalimantan, 5th century CE

References

- Bonnefoy, Yves (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-226-06456-7.

- SAHOO, P. C. (1994). "On the Yṻpa in the Brāhmaṇa Texts". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 54/55: 175–183. ISSN 0045-9801. JSTOR 42930469.

- Catalogue Of The Archaeological Museum At Mathura. 1910. p. 189.

- Rosenfield, John M. (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. University of California Press. p. 57.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 431–433. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- Houben, Jan E. M.; Kooij, Karel Rijk van (1999). Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in South Asian Cultural History. BRILL. p. 128. ISBN 978-90-04-11344-2.

- Ganguly, Dilip Kumar (1984). History and Historians in Ancient India. Abhinav Publications. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-391-03250-7.

- S. Supomo, "Chapter 15. Indic Transformation: The Sanskritization of Jawa and the Javanization of the Bharata in Peter S. Bellwood, James J. Fox, Darrell T. Tryon (eds.), The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, Australian National University, 1995