Yamen

A yamen (ya-men; simplified Chinese: 衙门; traditional Chinese: 衙門; pinyin: yámén; Wade–Giles: ya2-men2; Manchu: ᠶᠠᠮᡠᠨyamun) was the administrative office or residence of a local bureaucrat or mandarin in imperial China. A yamen can also be any governmental office or body headed by a mandarin, at any level of government: the offices of one of the Six Ministries is a yamen, but so is a prefectural magistracy. The term has been widely used in China for centuries, but appeared in English during the Qing dynasty.

Overview

Within a local yamen, the bureaucrat administered the government business of the town or region. Typical responsibilities of the bureaucrat includes local finance, capital works, judging of civil and criminal cases, and issuing decrees and policies.

Typically, the bureaucrat and his immediate family would live in a residence attached to the yamen. This was especially so during the Qing dynasty, when imperial law forbade a person from taking government office in his native province.

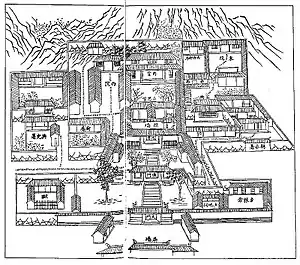

Yamens varied greatly in size depending on the level of government they administered, and the seniority of the bureaucrat's office. However, a yamen at a local level typically had similar features: a front gate, a courtyard and a hall (typically serving as a court of law); offices, prison cells and store rooms; and residences for the bureaucrat, his family and his staff.

At the provincial level and above, specialisation among officials occurred to a greater extent. For example, the three chief officials of a province (simplified Chinese: 三大宪; traditional Chinese: 三大憲; pinyin: Sàn Dà Xiàn; lit. 'the Three Great Laws') controlled the legislative and executive, the judicial, and the military affairs of the province or region. Their yamen would accordingly be specialised according to the functions of the office. The great yamens of the central government, located in the capital, are more exclusively office complexes.

The Yamen Runner in the Ming Dynasty

General

Yamen runner (Chinese: 衙役) is an occupation which served for yamen (Chinese: 衙门), the law enforcement department in ancient China. They worked as the lowest class in the government department which made them a bridge between the common people and the government.[1][2]

Classification

There were three kinds of yamen runner, zao (皂), zhuang (壮), kuai (快). But in fact, there were more different kinds in specific . Zao usually served around the court, Zhuang provided physical labor and Kuai were in charge of inspection, investigation, and arrest.

Zao

Zao acted as the officials' bodyguards. They usually followed behind the officials. During the trial, they would stand on both sides of the court to maintain order. They also performed the duties of escorting the prisoner, questioning the suspect and applying minor punishment. They had their own black uniform.[1]

Zhuang

Zhuang were comparable to modern security guards. Their main job was to guard the critical areas such as castle gates, the court, prison, and warehouse. They also patrolled on the streets. Most of them were picked from among strong civilians.[1]

Kuai

Kuais' duties included summoning defendants and witnesses to the court. They were usually asked to do the trips for the court, traveling long distances if necessary. During the tax season, they would be sent to remote areas to collect for the government. Therefore, Kuai had more contact with civilians than Zao and Zhuang. They didn't have their own uniform, but were required to hang a card on the waist belt to identify themselves.[1]

Social status

In the Ming Dynasty, due to their duties, yamen runners were considered as a debased class (jianmin, Chinese: 贱民), which is even lower than good commoners (liangmin, Chinese: 良民) such as farmers. It is the lowest stratum in society.[3][4]

Income

The salary provided by the court for the yamen runner was low compared to other jobs. The average daily salary was enough for only one meal.[1]

While the salary was not enough to live or raise a family on, working for the law enforcement department gave yamen runners some power that could be taken advantage of. The runners would charge a small fee from the litigants to cover the spendings. The prefects and magistrates acquiesced such a charging system as long as the amount is in a reasonable range. The Kuai, however, couldn't contact the litigants in the lawsuit cases. They would ask for money from the other debased classes like butchers and prostitutes. Such unwritten rule is called dirty regulation (Chinese: 陋规). Therefore, the actual income of the Kuai depended on their place of work; Kuai in large cities could easily collect a lot of money and Kuai in rural areas could be as poor as the homeless.[1]

Such corruption and extortion were rampant during Xuande Emperor reign. The prefects and magistrates just turn a deaf ear on their clerks blackmailing the lower classes. Xuande Emperor described them "licentious, greedy, and insatiably exploitative, [or] degenerate and worthless."[5]

Path into the occupation

Since the social status of yamen runners was low and the income was unstable (usually low), yamen runners were mostly formed by vagrants, especially among Kuai. They were often strong but uneducated.

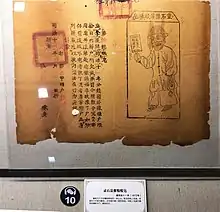

Paper Yamen Runner

A paper yamen runner (Chinese: 纸皂) is a piece of paper on which a yamen runner was drawn, and upon which is recorded an accusation or tax liability, as well as a demand for the recipient to appear in court or pay the tax. The prefects and magistrates issued this to the litigants or tax defaulters in the hope that they would voluntarily appear in court or pay tax in arrears. It’s unclear when the paper yamen runner was created, but literature about it can be found during the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Because it was tempting for yamen runners to take unlawful advantage of their position, magistrates would occasionally allow plaintiffs to take litigants to the court first. If a plaintiff failed to do so, the magistrate would issue a paper yamen runner. Only if both methods failed would an actual yamen runner be sent to arrest the litigant. In this way, fewer yamen runners were required. Such practices were typically employed only for mild crimes, however. For serious crimes such as murder, theft, gambling, and fights, the magistrate would still send yamen runners directly for the arrest.

After 1911

The institution of the yamen fell victim to the Wuchang Uprising and the Xinhai Revolution, after which warlords often became the ultimate authorities, in spite of Sun Yat-sen's best efforts to establish a Republic of China covering all of China. Sun Yat-sen tried to establish a form of self-government, or home rule, on a regional (or local) basis, but he found that he needed bureaucracy to run a country as big as China. Hence, new bureaucratic offices arose, thus replicating the functions of the Imperial yamens in many ways.

The term yamen is still used in colloquial Chinese today, however, to denote government offices. It sometimes carries negative connotations of an arrogant or inefficient bureaucracy, much as the term "mandarin" does in English.

Notable yamens

- The Zongli Yamen acted as an office of foreign affairs in the late Qing dynasty .

- The yamen at Kowloon Walled City, Hong Kong is an important historical site.

- The Presidential Palace (Nanjing) was modified from the "yamen" of the Viceroy of Liangjiang.

- The yamen of Neixiang County, in Henan, is the best preserved county-level yamen in mainland China today.

- The yamens of the six imperial Ministries of the Qing dynasty, in Beijing, were located within what is now Tiananmen Square, and were demolished in stages in the early to mid 20th century.

- The Qing Dynasty Taiwan Provincial Administration Hall in Taipei is the sole surviving Qing Dynasty government building in Taiwan.

References

- Li, Zongya 李宗亚. Three kinds of Yamen Runner in Yamen. 衙门中的三班衙役, Chinese & Foreign Entrepreneurs, 中外企业家, Editorial E-mail, 2014(29)

- Reed, Bradly W. (2000). Talons and teeth : county clerks and runners in the Qing dynasty. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3758-4. OCLC 1063409031.

- Moll-Murata, Christine. “Work Ethics and Work Valuations in a Period of Commercialization: Ming China, 1500–1644.” International Review of Social History, vol. 56, no. S19, 2011, pp. 165–195., doi:10.1017/s0020859011000514.

- Hansson, Anders (1996). Chinese outcasts : discrimination and emancipation in late imperial China. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10596-4. OCLC 1014973746.

- Nimick, Thomas G. “The Selection of Local Officials through Recommendations in Fifteenth-Century China.” T'oung Pao, vol. 91, no. 1/3, 2005, pp. 125–182. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4528998.