Yane Sandanski

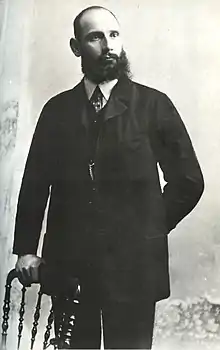

Yane Ivanov Sandanski (Bulgarian: Яне Сандански, Macedonian: Јане Сандански) (18 May 1872 – 22 April 1915), was a Macedonian Bulgarian revolutionary.[2] He is recognized as a national hero in both Bulgaria and North Macedonia.[3]

Yane Ivanov Sandanski | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 May 1872 |

| Died | 22 April 1915 (aged 42) Blatata location, near Pirin (village), Bulgaria |

| Other names | Jane Sandanski |

| Organization | Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee, later Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation |

.jpg.webp)

In his youth Sandanski was interested in Bulgarian politics and had a career as governor of the local prison in Dupnitsa. Then he was involved in the anti-Ottoman struggle, joining initially the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC), but later switched to the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organisation (IMARO). Sandanski became one of the leaders of the IMARO in the Serres revolutionary district and head of the left wing of the organisation. He supported the idea of a Balkan Federation, and Macedonia as an autonomous state within its framework, as an ultimate solution of the national problems in the area. During the Second Constitutional Era he became an Ottoman politician and entrepreneur, collaborating with the Young Turks and founded the Bulgarian People's Federative Party. Sandanski took up arms on the side of Bulgaria during the Balkan Wars (1912–13). Finally he was involved in Bulgarian public life again, but was eventually killed by the rivalling IMARO right-wing faction activists.[4]

Sandanski's legacy remains disputed among Bulgarian and Macedonian historiography today. Macedonian historians refer to him in an attempt to demonstrate the existence of Macedonian nationalism or at least proto-nationalism within a part of the local revolutionary movement at his time.[5] Despite the allegedly "anti-Bulgarian" autonomism and federalism of Sandanski,[6] it is unlikely he had developed Macedonian national identity in a narrow sensе,[7] or he regarded the Bulgarian Exarchists in Ottoman Macedonia as a separate nation from Bulgarians.[8] Contrary to the assertions of Skopje, his "separatism" represented a supranational project, not national. More, the compatriots, who convinced Sandanski to accept such leftist ideas, were Bulgarian socialists, most of whom were non-Macedonian in origin. The designation Macedonian then was an umbrella term covering different nationalities in the area and when applied to the local Slavs, it denoted mainly the regional Bulgarian community.[9] However, contrary to Bulgarian assertions, his ideas of a separate Macedonian political entity, have stimulated the subsequent development of Macedonian nationalism.

As initial member of the SMAC, which served directly the Bulgarian governmental interests,[10] and then of the left wing of the IMRO, which advocated the creation of a Balkan Federation, Yane Sandanski remains one of the most controversial[11] Bulgarian revolutionaries.[12] While the Bulgarian communist authorities mostly liked him for his leftist sympathies,[13] after the fall of communism he is described by some nationalist historians as a betrayer of the Bulgarian national interests in Macedonia.[14] Sandanski is portrayed by them as an Ottomanist, and collaborationist of the Young Turks, seen as Bulgarian enemies, and as the man who started the fratricidal war into the IMRO. He has been accused also of being transformed himself from a revolutionary into a businessperson whose political motivation became only the money earning. On the contrary, in North Macedonia, the positive historical myth on him, created in the times of Communist Yugoslavia is still alive. Since then the Macedonian historiography has emphasized the particularity of the IMRO's left wing,[15] while in fact Yugoslav communism and Macedonian nationalism are closely related.[16] Thus, he is portrayed by the Macedonian historians as a freedom fighter against the “Greater Bulgarian chauvinism” and the “Turkish yoke”. Sandanski has been also claimed recently by some Aromanians as an alleged compatriot, who sought only a limited autonomy for Macedonia in a business deal with the Ottoman Turks.[17][18]

Biography

Sandanski was born in the village of Vlahi near Kresna in Ottoman Empire on May 18, 1872.[19] His father Ivan participated as a standard-bearer in the Kresna-Razlog Uprising. After the crush of the uprising, in 1879 his family moved to Dupnitsa, Bulgaria, where Sandanski received his elementary education. From 1892 to 1894 he was a soldier in the Bulgarian army. Sandanski was an active supporter of the Radoslavov's wing of the Liberal Party and shortly after it came to power in February 1899, he was appointed head of the Dupnitsa Prison. Because of that, his name "Sandanski" distorted from "Zindanski" that comes from Turkish "Zindancı" (lit. Dungeon Keeper or Jailer).[20]

Yane Sandanski was involved in the Revolutionary Movement in Macedonia and Thrace and became one of its leaders. He joined initially the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee (SMAC) in 1895 during the Committee's cheta action into the Pomaks-inhabited regions of the Western Rhodopes.[21] In the next five years, Sandanski was a SMAC activist in the Pirin region, but in 1900 returned to become a director of the local prison in Dupnitsa. In 1901, Sandanski switched to the Internal Macedono-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Organization (IMARO). He built up the organization’s network of committees in the districts of Serres and Gorna Dzhumaja in the Pirin region, and that is why the people gave him the nickname "PirinTsar" (Pirinski Tsar). He was also one from the organizers of the Miss Stone Affair - America's first modern hostage crisis. On September 3, 1901, a Protestant missionary named Ellen Stone set out on horseback across the mountainous hinterlands of Macedonia and was ambushed by a band of armed revolutionaries. Sandanski was also active in the anti-Ottoman Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising. The Militias active in the region of Serres, led by Yane Sandanski and an insurgent detachment of the Macedonian Supreme Committee, held down a large Turkish force. These actions began on the day of the Feast of the Cross and did not involve the local population as much as in other regions, but were well to the east of Monastir and to the west of Thrace.

The failure of the Ilinden insurrection resulted in the eventual split of the IMARO into a left (federalist) faction in the Seres and Strumica districts and a right-wing faction (centralists) in the Bitola, Salonica and Uskub districts. The left-wing faction opposed Bulgarian nationalism and advocated the creation of a Balkan Socialist Federation with equality for all subjects and nationalities. The centralist faction of IMARO, moved towards Bulgarian nationalism as its regions became incursed of Serb and Greek armed bands, which started infiltrating Macedonia after 1903. The years 1905–1907 saw the split between the two factions, when in 1907 Todor Panitsa killed the right-wing activists Boris Sarafov and Ivan Garvanov in order of Sandanski. The Kjustendil congress of the right faction of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) in 1908, sentenced Sandanski to death, and led to a final disintegration of the organization.

After the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and during the Second Constitutional Era Sandanski (in association with Hristo Chernopeev, Chudomir Kantardziev, Aleksandar Buynov and others) contacted the Young Turks and started legal operation. After the disintegration of IMARO, they tried to set up the Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (MORO). Later, the congress for MORO's official inauguration failed and Sandanski and Chernopeev started to work towards a creation of one of the left political parties in the Ottoman Empire – People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section), whose headquarters was in Solun.[22] This federalist project was supposed to include different ethnic sections in itself, but this idea failed and the only section that was created was the faction of Sandanski, called Bulgarian section. In this way its activists only "revived" their Bulgarian national identification, as Sandanski's faction advocated the particular interests of the "Bulgarian nationality" in the Empire.[23][24][25][26][27] In 1909 the group around Sandanski and Chernopeev participated in the rally of the Young Turks to Istanbul that led to the deposition of sultan Abdul Hamid II from the throne. Sandanski dreamed about the creation of a Balkan Federative Republic according to the plans of the Balkan Socialist Federation and Macedonia as a part of that Federation.[28] He demanded that the IMARO should embrace all nationalities in the region, not only Bulgarians.[29]

In this way it would be possible to create a healthy system aimed at the organisation of a mass uprising.[30] Later Sandanski and his faction actively supported the Bulgarian army in the Balkan wars of 1912–1913, initially with the idea, that their duty is to fight for autonomous Macedonia,[31][32] but later fighting for Bulgaria.[33] Οbserving the atrocity of Serbs over the local population, former IMRO members began restoration of the organizational network. In the same period a group around Petar Chaulev began negotiations with the Albanian revolutionaries. The temporary Albanian government proposed to them a common revolt to be organized and risen. The negotiations from the part of the Organization had to be carried by Petar Chaulev. The Bulgarian government believed however, that it would not come to a new war with Serbia, so it did not attend the negotiations. However, later, in June 1913 the Bulgarian government sent in Tirana Yane Sandanski for new negotiations. He gave an interview for the newspaper "Seculo", where he said that he came to agreement with the Albanians and that from the Bulgarian side there would be organized bands and assaults. So he helped the preparation of the Ohrid-Debar Uprising, organised jointly by IMRO and the Albanians of Western Macedonia.[34] After the wars, Pirin Macedonia was ceded in 1913 to Bulgaria and Sandanski resettled again in the Kingdom where he was killed in 1915 by his political opponents.

Controversy

The Macedonian liberation movement consisted of three major factions. Led by his excessive ambitions, Sandanski came into conflict with the majority — the Centralists in IMARO and the Varhovists. Although initially a member of the Bulgarian nationalistic Varhovists band, later Yane Sandanski and his Serres group (the Federalists) proclaimed a fight for an autonomous Macedonia which was to be included in a Balkan Socialist Federation. In this manner, the policy of Sofia was completely identified to the adversary character of Athens and Belgrade.[35][36] The activists of Serres nonetheless stipulated that the Macedonian Question could not be resolved if it is formulated as a part of a Bulgarian national question. After the Ilinden Uprising, this Group insisted on cooperation with all ethnic and religious groups in the Ottoman Empire and envisioned the inclusion of Macedonia and the district of Adrianople in a Balkan Federation.[37] However the idea of Macedonian autonomy was strictly political and did not imply a secession from Bulgarian ethnicity, even as it was seen at a later stage of the struggle by the group around Sandanski, that espoused a number of classical liberal ideas intermingled with socialism, imported from Bulgaria.[38][39][40]

On the other hand, the bigger fraction (the Centralists), as well as that of the other revolutionary organization - Macedonian Supreme Committee - Varhovists, (most of which followers joined the "Centralists", after its dissolution in 1903) aimed also at autonomy. But they did not expected inclusion in a Balkan Socialist Federation and had not so extreme policy by their relation to Sofia. These political differences led to sharp conflict between them.

Arguably Sandanski's greatest sin in the context of the whole movement were the assassinations of the vojvod Michail Daev and later of Ivan Garvanov and Boris Sarafov, both members of the IMARO's Central Committee. He came to regret these and other murders later.[41][42] Because of that he was even sentenced to death by the Centralists. The Bulgarian authorities investigated the assassinations and suspected Sandanski was the main force behind them. On the other hand, he was amnestied by the Bulgarian Parliament after the support he gave to the Bulgarian Army during the Balkan wars.

There was, a long history of friction between the Bulgarian Exarchate and the Organization, since those more closely connected with the Exarchate were moderates rather than revolutionaries. Thus the two bodies had never been able to see eye to eye on a number of important issues touching the population in Thrace and Macedonia. In his regular reports to the Exarch, the Bulgarian bishop in Melnik usually referred to Yane as the wild beast and deliberately spelt his name without capital letters. Despite being an extreme leftist, he had never rejected the Bulgarian Exarchate as an institution, or denied that it had a role to play in the life of the Macedonian Bulgarians.[43] Sandanski also collaborated later with the Young Turks, opposing other factions of IMARO, which fought against the Ottoman authorities in this period.

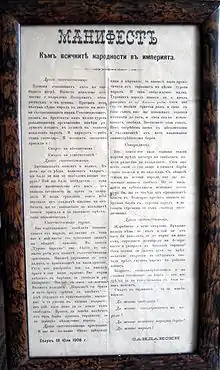

During the first days of Young Turk Revolution, the collaboration of the Macedonian leftists with the Ottoman activists was stated in a special Manifesto to all the nationalities of the Empire.[44] The loyalty to the Empire declared by Sandanski deliberately blurred the distinction between Macedonian and Ottoman political agenda. This ideological transition was quite smooth as long as the rhetoric of Macedonian autonomist supra-nationalism was already quite close to the Ottomanist idea of the so-called unity of the elements.[45] During the honeymoon of Serres revolutionaries and Ottoman authorities, it was the internationalist ideas of Bulgarian socialist activists that left their stamp on Sandanski's agenda: what was seen as national interests had to be subdued to the pan-Ottoman ones in order to achieve a supra-national union of all the nationalities within a reformed Empire. After Bulgaria lost the Balkan Wars and as result most of Macedonia was ceded to Greece and Serbia, Sandanski attempted to organize the assassination of Bulgarian Tsar Ferdinand I, but it failed. He and his wing officially supported then the Russophiles from the Democratic Party.

The Centralists organised several unsuccessful assassination attempts against Sandanski. They came closest to achieving their goal in Thessaloniki, where Tane Nikolov managed to kill two other Federalists and heavily wounded Sandanski. Eventually, Sandanski was killed near the Rozhen Monastery on April 22, 1915, while travelling from Melnik to Nevrokop, by local IMARO activists.[46]

Legacy

While Sandanski's legacy remains disputed among Bulgarian and Macedonian historiography, there have been attempts among international scholars to reconcile his conflicting and controversial activity. According to the Turkish professor of history Mehmet Hacısalihoğlu, who is interested in nation-building in the late Ottoman Empire,[47] it is very difficult to find a definitive answers to some ticklish questions related to Sandanski's biography. Hacısalihoğlu's opinion is that Sandanski was de facto a betrayer of the national Bulgarian interests in Macedonia, collaborating with the Young Turks, supporting the idea of the autonomy of the region into the Ottoman Empire, and opposing its incorporation into Bulgaria. That would allow him to maintain his political role, as one of the native leaders in the region. However, this does not mean, he regarded the Bulgarian Macedonian population as a separate Macedonian nation.[48] Also, all the main ideologists, who indoctrinated Sandanski with these leftist ideas, were socialists from Bulgaria proper.[49] Mercia MacDermott who is author of a biographical book on Sandanski, has admitted she has had a real battle over such controversial figure.[50] Nevertheless, she has described him as Bulgarian revolutionary, who under the influence of leftist ideas, tried to solve the Macedonian Question by uniting all the Balkan peoples.[51]

As a whole, during the early 20th century the idea of a separate Macedonian identity was promoted only by small circles of intellectuals, but the majority of the Slavic people in Macedonia considered themselves to be Bulgarians.[52][53][54][55][56] The turn-of-the-century Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, was in fact a largely pro-Bulgarian oriented and its members had ethnic Bulgarian identity,[57][58][59] including Sandaski.[60]

The IMRO right-wing publicist Hristo Silyanov provides a position of Sandanski’s where he states that the solution of the Macedonian question is not the unity with Bulgarians, and that the Macedonian population had to emancipate itself as a self-determining (or an independent) people. However Siljanov described all IMARO revolutionaries as Bulgarians and used the term Macedonian only as regional designation.[61]

In North Macedonia Sandanski is considered a national hero and one of the most prominent revolutionary figures of the 20th century. However some Macedonian mainstream specialists on the history of local revolutionary movement, like Academician Ivan Katardžiev and PhD. Zoran Todorovski, argue that the political separatism of Sandanski represented a form of early Macedonian nationalism,[62] asserting that at that time it was only a political phenomenon, without ethnic character. Both define all Macedonian revolutionaries from that period as "Bulgarians", as products of the Bulgarian educational system and Bulgarian Church, which had a policy of producing “Bulgarian national consciousness” in its Exarchist schools.[63][64] According to them Macedonian identity arose mostly after the First World War and Sandanski identified himself as Bulgarian too.[65] Dimitrija Čupovski under the pseudonym Strezo writes that Sandanski was a Bulgarian agent, bodyguard of the Bulgarian prince and an ordinary criminal.[66]

The IMRO right-wing publicist Stoyan Boyadziev has described Sandanski as extremely controversial Bulgarian revolutionary, whose separatist асtivitу however, produced as a whole Macedonian nationalism.[67] Today, Sandanski is one of the names mentioned in the National anthem of North Macedonia. In Bulgaria the communist regime appreciated Sandanski because of his socialist ideas and honoured him by renaming the town Sveti Vrach to Sandanski, in 1949. In the years after the Fall of Communism some right-wing Bulgarian historians have been keen to discredit his reputation.[68] Sandanski Point on the E coast of Ioannes Paulus II Peninsula, Livingston Island, Antarctica was named after him by the Bulgarian Antarctic Expedition.

References

- Macdermott Mercia, For Freedom and Perfection. The Life of Yane Sandansky, 1988, Published by Journeyman, London, ISBN 1-85172-014-6, pg 403.

- Per Julian Allan Brooks' thesis the term ‘Macedo-Bulgarian’ (incl. Sandanski) refers to the Exarchist population in Macedonia which is alternatively called ‘Bulgarian’ and ‘Macedonian’ in the documents. For more see: Managing Macedonia: British Statecraft, Intervention and 'Proto-peacekeeping' in Ottoman Macedonia, 1902-1905. Department of History, Simon Fraser University, 2013, p. 18. The designation ‘Macedo-Bulgarian’ is used also by M. Şükrü Hanioğlu and Ryan Gingeras. See: M. Şükrü Hanioğlu, Preparation for a Revolution: The Young Turks, 1902-1908 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 244; Ryan Gingeras, “A Break in the Storm: Reconsidering Sectarian, Violence in Ottoman Macedonia During the Young Turk Revolution” The MIT Electronic Journal of Middle East Studies 3 (Spring 2003): 1. Gingeras notes he uses the hyphenated term to refer to those who “professed an allegiance to the Bulgarian Exarch.” Mehmet Hacısalihoğlu has used in his study "Yane Sandanski as a political leader in Macedonia in the era of the Young Turks" the terms Bulgarians-Macedonians and Bulgarian Macedonians; (Cahiers balkaniques [En ligne], 40, 2012, Jeunes-Turcs en Macédoine et en Ionie).

- The way Bulgarian and Macedonian history and identities are intertwined is exemplified by the dispute over the identity of revolutionary heroes such as Gotse Delchev and Yane Sandanski. Bulgarian nationalists, for example, ridicule their Macedonian counterparts' identification with Sandanski, since archival documents refer to him as Bulgarian. For more see: Aarbakke Vemund, Images of imperial legacy: The impact of nationalizing discourse on the image of the last years of Ottoman rule in Macedonia, p. 121, in Images of Imperial Legacy, Modern Discourses on the social and cultural impact of Ottoman and Habsburg rule in Southeast Europe by Editor(s): Tea Sindbæk, Maxmilian Hartmuth, ISBN 3643108508, 2011; pp. 115-128.

- Dimitar Bechev, Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia; Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Edition 2, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019; ISBN 1538119625, p. 263.

- In his youth Sandanski was a member of the Bulgarian nationalist Supreme Macedonian Committee, which main idea was the direct unification of Macedonia with Bulgaria, but later switched to the IMRO. However, the first name of the IMRO was "Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees", which was later changed several times. Initially its membership was restricted only for Bulgarians. It was active not only in Macedonia but also in Thrace (the Vilayet of Adrianople). Since its early name emphasised the Bulgarian nature of the organisation by linking the inhabitants of Thrace and Macedonia to Bulgaria, these facts are still difficult to be explained from the Macedonian historiography. They suggest that IMRO revolutionaries in the Ottoman period did not differentiate between ‘Macedonians’ and ‘Bulgarians’. Moreover, as their own writings attest, they often saw themselves and their compatriots as ‘Bulgarians’ and wrote in Bulgarian standard language. For more see: Brunnbauer, Ulf (2004) Historiography, Myths and the Nation in the Republic of Macedonia. In: Brunnbauer, Ulf, (ed.) (Re)Writing History. Historiography in Southeast Europe after Socialism. Studies on South East Europe, vol. 4. LIT, Münster, pp. 165-200 ISBN 382587365X.

- The Internal organization's leaders rejected the national-separatist idea of promoting the Macedonian into a distinct language. They opposed Misirkov's program and his book seems to have been burned in Sofia by TMORO activists. When, in 1905, Čupovski tried to organize a "Pan-Macedonian conference" in Veles, he was expelled from the town by a local chief of the Internal organization. At the same time, the Macedonian nationalists did not recognize their program even in the allegedly "anti-Bulgarian" autonomism of Sandanski and, in 1914, accused him of "non-Macedonian" activity. For more see: Tchavdar Marinov We, the Macedonians - The Paths of Macedonian Supra-Nationalism (1878–1912) in We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe, edited by Diana Mishkova, 107–138. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, 2009, p. 133.

- It is nevertheless doubtful that Sandanski and the other leftists of this period developed Macedonian nationalism stricto sensu. During the constitutional regime established by the Young Turks, Sandanski and his followers set up a “People's Federative Party” that was supposed to include a number of ethnic sections, each one representing a distinct "nationality" of Macedonia... This federalist project, however, failed and the only section that was set up within the "People's Federative Party" was the one of Sandanski himself and of his "co-nationals," which was actually called the "Bulgarian section." For more see: Marinov, Tchavdar. “Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian Identity at the Crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian Nationalism. In: Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One, pp. 273–330; ISBN 9789004250765, Brill, 2013, p. 303.

- In Macedonian historiography, Sandanski has been portrayed as a fighter for Macedonian independence against the Young Turks and the Turkish rule in Macedonia. I think that this interpretation is highly problematic. He certainly stood for the autonomy of Macedonia, but this does not mean that he regarded the Slavic Christians in Macedonia as a separate nation—namely, a “Macedonian nation.” For more see: Mehmet Hacısalihoğlu, «Yane Sandanski as a political leader in Macedonia in the era of the Young Turks», Cahiers balkaniques [En ligne], 40 | 2012, mis en ligne le 21 mai 2012, DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ceb.1192 .

- Bechev, Dimitar. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, Introduction.

- Supreme Macedonian Revolutionary Committee, which had emerged in Sofia in 1895 served Bulgarian state interests in Macedonia. Opponents on the left would designate people on the right as ‘‘Vrhovists’’ (Supremists) and their pro-Bulgarian program and aims as ‘Vrhovizam’’ (Supremism). For more see: Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History Hoover Institution Press Publication, Hoover Press, 2013, ISBN 081794883X, p. 120.

- Waller, Diane, "Mercia MacDermott: A Woman of the Frontier" p. 181; in Black Lambs and Grey Falcons (2nd ed.). Allcock, John B. and Young, Antonia, eds. (2000). Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 166–186.

- Aykut Kansu, The Revolution of 1908 in Turkey. Armenian Research Center collection. Volume 58 of Studies in Asian Art and Archaeology; BRILL, 1997; ISBN 9004107916, pp. 163-168.

- Sfetas, Spyridon. (2017). The Fusion of Regional and Cold War Problems: The Macedonian Triangle Between Greece, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, 1963–80; in The Balkans in the Cold War, Svetozar Rajak et al., Springer, ISBN 1137439033, pp.307-329

- James Frusetta, Common Heroes, Divided Claims: IMRO between Macedonia and Bulgaria, in John R. Lampe and Mark Mazower, eds., Ideologies and National Identities: The Case of Twentieth-Century Southeastern Europe; Central European University Press, 2004, ISBN 9639241822, pp. 110-121.

- Igor Despot, The Balkan Wars in the Eyes of the Warring Parties: Perceptions and Interpretations; iUniverse, 2012, ISBN 1475947038, p. 15.

- Roumen Daskalov, Diana Mishkova as ed., Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume Two: Transfers of Political Ideologies and Institutions, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 9004261915, p. 499.

- Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton University Press, 2018, ISBN 0691188432, p. 270.

- The name Vlahi, which means Vlachs, was given to the native village of Sandanski by the surrounding Slavic population. It was founded by Vlachs in the late Middle Ages. However, they were Bulgarianized even before the beginning of the Ottoman rule. According to Vasil Kanchov's statistics, at the end of the 19th century the village had a population of 1,850 Bulgarians and not a single Vlach. For more see: Хр. Христов и колектив, Енциклопедия "Пирински край" в два тома. Том 1: А-М, Редакция "Енциклопедия", 1995, Благоевград, ISBN 954-90006-1-3, стр. 340.

- Mercia MacDermott. For Freedom and Perfection. The Life of Yane Sandansky], 1988, Published by Journeyman, London, ISBN 978-1-85172-014-9, OCLC 16465550, pg. 1.

- Uzer, Tahsin, Mekadonya Eşkiyalık Tarihi ve Son Osmanlı Yönetimi, 3. edition, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 1999 ISBN 975-16-1119-9 p. 118 (in Turkish)

- Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, p. 196.

- We, the People. Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe. Diana Mishkova et al. Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, p. 130.

- Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One, Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, p. 303.

- Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Коста Църнушанов, Унив. изд. "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992, стр. 101.

- When, at the Praty's Congress, some more extreme left-winger began to attack the Bulgarian Exarchate during a debate on education, Yane, who was chairing the session, said: Leave the Exarchate alone! The situation in Turkey is still fluid. There was a great commotion, and Yane adjourned the session. During the interval, he went over to the delegate who had attacked the Exarchate and said: You know nothing! If it should so happen that the Bulgarians in Macedonia don’t get what they want, I shall defend the Exarchate with a weapon in my hand. Mercia MacDermott. For Freedom and Perfection. The Life of Yane Sandansky, 1988, Journeyman, London, ISBN 1-85172-014-6, pg. 425.

- As an organ of the Bulgarian People's Federative Party, Narodna Volya defends and expresses the interests mainly of that part of the Bulgarian population, which comprises its predominant majority, and which is the most important element in that party-the petty owners deprived of all state protection, the landless or poor farmers, petty shopkeepers, craftsmen and merchants. These are the social strata whose interests today are the interests of the Bulgarian nationality in the Empire. We consider that these interests require, in the first place, the strengthening of the constitutional regime, the expansion of liberties and the extension of reforms in the administrative and economic system. Only in this way can we create conditions for the raising of the standard of living and the prosperity of the Bulgarians in the Empire. Excerpt from a leading article entitled 'Our Positions' in the newspaper Narodna Volya, explains the demands of the Bulgarian People's Federative Party; Newspaper Narodna Volya, Soloun, No. 1, Jan. 17th, 1909; the original is in Bulgarian. /The newspaper Narodna Volya subtitled 'Organ of the Bulgarian People's Federal Party,' was the organ of the left faction in the Macedonian-Adrianople movement at the time of the Hürriyet, prepared the ground ideologically for the founding of the People's Federative Party, the Bulgarian section of which was set up at the Congress in August 1909./ Macedonia: Documents and Materials. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 1978.

- If this attitude were not peculiar and different in comparison with their attitude towards the other nationalities in the Empire, we would undoubtedly not even mention the name of the Bulgarian nationality to which we belong. Our basic principle is to struggle for the rights and liberties of all nationalities, without exception, and we strive for the complete equality of all the subjects of the Ottoman Empire, irrespective of nationality and religion. From this standpoint, we shall not hesitate, in the least, to come out in defence of any nationality, provided we are convinced that it is being discriminated against and is below the existing level of liberty and justice enjoyed by all other nationalities. We shall not hesitate either to turn against our own nationality, if it were given some advantages and privileges to the disadvantage of the other nationalities and if its privileged position compromised the regime of universal political and civil equality in the country. A newspaper article in Konstitoutsionna Zarya entitled 'The Peculiar Attitude of the Government towards the Bulgarian Nationality'. November 26th, 1908; the original is in Bulgarian. /A newspaper expressed the views of the left faction in the organization - the group of Yane Sandanski, after the Young Turk Revolution. At the beginning of 1909 it merged with the newspaper Edinstvo, and continued to appear under the name Narodna Volya./ Macedonia: Documents and Materials. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 1978.

- On no account must the population be deceived into hoping for outside help. It must rely on its own forces, and the Organization’s centre of gravity must be shifted from the cheti to the mass of the people, with the cheti acting chiefly as instructors and inspectors. All those who are ‘discontented with the existing regime’ must be brought into the Organization, and this must be understood as meaning not only Bulgarians, but all the nationalities inhabiting the Organization’s territory. Balkan Federation is indicated as an ultimate solution of the national problem, as ‘the sole way for the salvation of all’. See: Pavel Deliradev, Razvitieto na federativnata ideya, Makedonska misal, Book 5-6, 1946, pp. 203-208; also "For freedom and perfection. The Life of Yané Sandansky", Mercia MacDermott, Journeyman, London, 1988, pp. 152-153.

- "Today, all of us, Turks, Bulgarians, Greeks, Albanians, Jews and others, we have all sworn that we will work for our dear Fatherland and will be inseparable, and we will all sacrifice ourselves for it, and, if necessary, we will even shed our blood." - This part of Yané's speech held in the town of Nevrokop during the Young Turk Revolution is quoted from a hand-written leaflet, bearing the seal of the Razlog Committee for Union and Progress, and a price, i.e. the leaflet was one of many copies made for sale. The leaflet was found among the papers of Lazar Kolchagov of Bansko, and was published by Ivan Diviziev in Istoricheski Pregled, 1964, Book 4 (Nov Dokument za Yané Sandansky).

- "Long ago you are regarding our Macedonian-Adrianopole question only as Bulgarian question. The struggle we are on, you consider as the struggle for triumph of the Bulgarian nationality over the others which are living with us. Let forget henceforth who is Bulgarian, who is Greek, who is Serbian, who is Vlah, but remember who is underprivileged slave." - A letter to the Greek citizens of Melnik, (Революционен лист (Revolutionary Sheet), № 3, 17.09.1904)

- Ј. Богатинов - "Спомени", бр.11 од в. "Доброволец", 1945 г.

- According to Todor Romov, Jane Sandanski’s follower from the village of Rozhen, Pirin Macedonia, Sandanski said: “Bulgaria wants to conquer us, to absorb us. They don’t wanna help us. Remember! Even the Ottoman-Turkish regime was better than the eventual Bulgarian one, because during the Turkish regime, at least we had an idea to fight for, on the other hand – Bulgarians would eat us.“ (Стойко Стойков. Табy: Време на страх и страдание - Преследването на Македонците в България по времето на комунизма (1944-1989) - Сборник спомени и документи, pg. 331, Изд.: Дружество на репресираните Македонците в България, Благоевград, 2014 г.)

- The Russian journalist Viktorov-Toparov, who met Yané in May 1913, wrote: At the beginning of 1913, when the Serbian and Greek occupation regime forced the Macedonian Bulgarians once again to consider the fate of their country, serious doubts had assailed Sandanski. And I shall always remember that evening in 1913 when Sandansky came to me to confide his doubts and vacillations: "There, look this always happens when someone is freed by force of arms! How fine it would have been if Macedonia could have freed herself! But now it's happened, our duty is to fight alongside Bulgaria, and for Bulgaria" - Sŭvremena Misŭl, 15.V.1915, pp. 24-25, as citted by Mercia MacDermott. For Freedom and Perfection. The Life of Yane Sandansky, 1988, Journeyman, London, ISBN 978-1-85172-014-9, p. 452.

- ИДЕЯТА ЗА АВТОНОМИЯ КАТО ТАКТИКА В ПРОГРАМИТЕ НА НАЦИОНАЛНООСВОБОДИТЕЛНОТО ДВИЖЕНИЕ В МАКЕДОНИЯ И ОДРИНСКО, 1893-1941, Димитър Гоцев, Изд. на БАН, София, 1983; 1912- 1919 г.

- The Balkan Wars in the Eyes of the Warring Parties: Perceptions and Interpretations, Igor Despot, iUniverse, 2012, ISBN 1475947054, p. 22.

- Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One, Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, pp. 302-303.

- Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. 75.

- The leaders of the VMK were Bulgarian officers, Macedonian-born or descended, who were close to Bulgarian Prince Ferdinand of Coburg (ruled 1887 – 1918) and the willing tools of his self-exalting adventures. Though they repeatedly urged a speedy uprising, they had little faith in the strength of the internal movement, nor were they sensitive to the danger of Macedonia's partition, a threat that caused the BMORK to fight for Macedonia's autonomy within the Turkish state in the first place, rather than for her incorporation within Bulgaria... Autonomy, in other words, was as good as independence. Moreover, from the Macedonian perspective, the goal of independence by autonomy had another advantage. Gotse Delchev (1872 – 1903) and the other leaders of the BMORK were aware of Serbian and Greek ambitions in Macedonia. More important, they were aware that neither Belgrade nor Athens could expect to obtain the whole of Macedonia and, unlike Bulgaria, looked forward to and urged partition of this land. Autonomy, then, was the best prophylactic against partition – a prophylactic that would preserve the Bulgarian character of Macedonia's Christian population despite the separation from Bulgaria proper...The revived Internal Organization was increasingly under the influence of the VMK, though a left wing, associated with the Serres guerrilla group of Jane Sandanski, kept alive the autonomist tradition of Delchev, who had fallen to a Turkish ambush in 1903... "The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics", by Ivo Banac, Cornell University Press, 1984, pp. 314-317.

- Psilos, Christopher (2000) The Young Turk revolution and the Macedonian question 1908-1912, University of Leeds. Chapter 5.7 The Serres Faction and the Creation of the Bulgarian National Federal Party (B.N.F.P.) pp. 98 - 103..

- Considering all these elements, the Macedonian supra-nationalism may seem to be a kind of “mini-Ottomanism,” i.e., a translation of the Empire’s ideology into the smaller scope of Macedonia (and the Adrianople Thrace) as well as into the language of a liberation movement. Ironically but—from this point of view—not surprisingly, in 1908, it was exactly the stubborn left autonomists from Serres department who found a common language with their former enemies in the face of the Young Turks’ Committee of Union and Progress... The “anti-Bulgarian” character of Sandanski’s “Manifesto” still did not mean a Macedonian nationalism, not only because of the loyalty declared to the Empire, but also because its author was in fact Pavel Deliradev, a socialist who was non-Macedonian in origin... Thus, a number of classical liberal ideas, put forward in the Young Turks’ constitutionalism, intermingled with some characteristics of socialism, imported from Bulgaria. We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe, Diana Mishkova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, p. 129

- We went back. We told Yané what had happened, and he was silent as though struck dumb. He was silent, and sighed; only at one time he said: "We’re all Bulgarians, Tatso, and yet we kill each other to no useful purpose whatsoever. This futile bloodshed weighs heavy upon me. . . What do you think?" ‘What could I say to him? I was a simple chetnik. I’m telling you, those were troubled times, and there was plenty of unnecessary bloodshed. . . As for Yané, bright soul, he grieved over everything. As cited by Mercia MacDermott, For Freedom and Perfection. The Life of Yane Sandansky, p. 187 from the memoirs of Atanas Yanev, Eho, No. 21 (590), 26.V.1972.

- ‘. . . It was somewhere around 1905-1906. At that time, the Supremists—Ferdinand’s generals, as we called them—appeared in our part of the country as well. And they managed to get a foothold in the village of Lyubovka. "We are not going to stand for this," Yané decided, and collected a group of us. "Go and wake up Lyubovka! See to it that there’s no bloodshed!" (The words are quoted in the memoirs of his adherent Atanas Yanev and published in "Eho" newspaper, 26.05.1972) as citted by Mercia MacDermott, For Freedom and Perfection. The Life of Yane Sandansky p. 186.

- When, at the People Federative Party Congress, some more extreme left-winger began to attack the Exarchate during a debate on education, Yané, who was chairing the session, rose to his feet and said: ‘Leave the Exarchate alone! The situation in Turkey is still fluid.’ There was a great commotion, and Yané adjourned the session. During the interval, he went over to the delegate who had attacked the Exarchate and said: ‘You know nothing! If it should so happen that the Bulgarians in Macedonia don’t get what they want, I shall defend the Exarchate with a weapon in my hand.(Dnevnik, 11.VIII.1909. The debate in question took place on 7.VIII.1909.)

- Sandanski called his compatriots to discard the propaganda of official Bulgaria in order to live together in a peaceful way with the Turkish people.(Adanır, Ibid., 258.)

- Andonov-Poljanski et al., Ibid., 543-546

- The fifty biggest assaults in Bulgarian history, Blagov, Krum 50-те най-големи атентата в българската история. Крум Благов. Издателство Репортер. 21 September 2000. ISBN 954-8102-44-7

- Yıldız University, Department of Political Science and International Relations, Prof. Dr. Mehmet Hacısalihoğlu.

- Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales, Yane Sandanski as a political leader in Macedonia in the era of the Young Turks, Mehmet Hacısalihoğlu, Cahiers balkaniques, issue 40, 2012: Jeunes-Turcs en Macédoine et en Ionie.

- Igor Despot, The Balkan Wars in the Eyes of the Warring Parties: Perceptions and Interpretations, iUniverse, 2012, ISBN 1475947038, p. 25.

- John B. Allcock, Antonia Young as ed., Black Lambs & Grey Falcons: Women Travellers in the Balkans, Berghahn Books, 2000, ISBN 1571817441, p. 181.

- See abstract from the book "For freedom and perfection: the life of Yané Sandansky".

- During the 20th century, Slavo-Macedonian national feeling has shifted. At the beginning of the 20th century, Slavic patriots in Macedonia felt a strong attachment to Macedonia as a multi-ethnic homeland. They imagined a Macedonian community uniting themselves with non-Slavic Macedonians... Most of these Macedonian Slavs also saw themselves as Bulgarians. By the middle of the 20th. century, however Macedonian patriots began to see Macedonian and Bulgarian loyalties as mutually exclusive. Regional Macedonian nationalism had become ethnic Macedonian nationalism... This transformation shows that the content of collective loyalties can shift.Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Ethnologia Balkanica Series, Klaus Roth, Ulf Brunnbauer, LIT Verlag Münster, 2010, ISBN 3825813878, p. 127.

- Up until the early 20th century and beyond, the international community viewed Macedonians as regional variety of Bulgarians, i.e. Western Bulgarians.Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe, Geographical perspectives on the human past : Europe: Current Events, George W. White, Rowman & Littlefield, 2000, ISBN 0847698092, p. 236.

- "Most of the Slavophone inhabitants in all parts of divided Macedonia, perhaps a million and a half in all – had a Bulgarian national consciousness at the beginning of the Occupation; and most Bulgarians, whether they supported the Communists, VMRO, or the collaborating government, assumed that all Macedonia would fall to Bulgaria after the WWII. Tito was determined that this should not happen. "The struggle for Greece, 1941-1949, Christopher Montague Woodhouse, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1-85065-492-1, p. 67.

- "At the end of the WWI there were very few historians or ethnographers, who claimed that a separate Macedonian nation existed... Of those Slavs who had developed some sense of national identity, the majority probably considered themselves to be Bulgarians, although they were aware of differences between themselves and the inhabitants of Bulgaria... The question as of whether a Macedonian nation actually existed in the 1940s when a Communist Yugoslavia decided to recognize one is difficult to answer. Some observers argue that even at this time it was doubtful whether the Slavs from Macedonia considered themselves to be a nationality separate from the Bulgarians. "The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world", Loring M. Danforth, Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-691-04356-6, pp. 65-66.

- Kaufman Stuart J. Modern hatreds: the symbolic politics of ethnic war, 2001, Cornell University Press, New York, ISBN 0-8014-8736-6, pg. 193; The key fact about Macedonian nationalism is that it is new: in the early twentieth century, Macedonian villagers defined their identity religiously—they were either "Bulgarian," "Serbian," or "Greek" depending on the affiliation of the village priest. While Bulgarian was most common affiliation then, mistreatment by occupying Bulgarian troops during WWII cured most Macedonians from their pro-Bulgarian sympathies, leaving them embracing the new Macedonian identity promoted by the Tito regime after the war.

- The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world|, Loring M. Danforth, Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 0691043566, pg. 64: The political and military leaders of the Slavs of Macedonia at the turn of the century seem not to have heard Misirkov's call for a separate Macedonian national identity; they continued to identify themselves in a national sense as Bulgarian rather than Macedonians.[...] In spite of these political differences, both groups, including those who advocated an independent Macedonian state and opposed the idea of a greater Bulgaria, never seem to have doubted “the predominantly Bulgarian character of the population of Macedonia”

- The IMARO activists saw the future autonomous Macedonia as a multinational polity, and did not pursue the self-determination of Macedonian Slavs as a separate ethnicity. Therefore, Macedonian was an umbrella term covering Bulgarians, Turks, Greeks, Vlachs, Albanians, Serbs, Jews, and so on.” Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, Introduction.

- Contrary to the assertions of Skopje's historiography, Macedonian revolutionaries clearly manifested Bulgarian national identity. Their Macedonian autonomism and “separatism” represented a strictly supranational project, not national. Entangled Histories of the Balkans:, Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, BRILL, 2013, ISBN 900425076X, p. 303.

- IMRO was founded in 1893 in Thessaloníki. Its early leaders included Damyan Gruev, Gotsé Delchev, and Yane Sandanski, men who had a Macedonian regional identity and a Bulgarian national identity. Their goal was to win autonomy for a large portion of the geographical region of Macedonia from its Ottoman Turkish rulers. Encyclopædia Britannica online, Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).

- Hristo Silyanov, Освободителнитѣ борби на Македония, II, Sofia, 1943, pg. 498-515.

- Ivan Katardžiev, Makedonija sto godini po Ilindenskoto vostanie, Skopje: Kultura, 2003, 54-69

- Зоран Тодоровски, Уште робуваме на старите поделби. Разговор со приредувачот на Зборникот документи за Тодор Александров, весник Трибуна од 27.06.2005 г.

- Ivan Katardžiev: Што се однесува до „бугарштината“ на нашите дејци, мора да се знае тоа дека нашите луѓе поминаа низ бугарски образовни институции, низ школите на Егзархијата, која ја спорведуваше бугарската великодржавна политика. Целта на тие школи беше во Македонија да создаваат интелигенција со бугарска свест и таа даде свои резултати од гледна точка на бугарските интереси. (“I believe in the Macedonian national immunity” Archived 2015-07-08 at the Wayback Machine)

- Сто години Илинден или сто години Мисирков? История и политика в Република Македония през 2003. Чавдар Маринов. Вестник "Култура", бр.19/20, 30 април 2004 г. На втория й ден се стигна до шумен скандал между Ристовски и Катарджиев, след като последният подчерта, че в момента на излизане на Мисирковия манифест в Македония съществувала българска нация и че началото на македонската идентичност трябва да се търси едва след Първата световна война.

- Dimitar, Chupovski (1914). "Dimitar Chupovski from the village of Papradishte, Veles region, Vardar Macedonia - "The case of J. Sandanski - not a Macedonian case", published in the newspaper "Makedonskij Golos", year II, issue. 11, Petrograd, Russia, November 20, 1914" (PDF). Strumski Online Library. Archived from the original on 2020.

- Cтoян Бояджиев: Истинският лик на Яне Сандански, Cофия, 1994, cтp. 21.

- Bulgaria, Jonathan Bousfield, Rough Guides, Dan Richardson, Richard Watkins, Edition: 4, Rough Guides, 2002, ISBN 1-85828-882-7, p. 160.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yane Sandanski. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Yane Sandanski |

- Mercia MacDermott. For Freedom and Perfection. The Life of Yane Sandansky, 1988, Published by Journeyman, London, ISBN 1-85172-014-6, ISBN 978-1-85172-014-9, OCLC 16465550

- Memoirs of Yane Sandanski (original edition in Bulgarian)

- Pavel Deliradev: Jane Sandanski (Biography, 1946)

- Hristo Konstantinov: The Chieftain (Jane Sandanski) (Biography, 1939)