Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) of the Ottoman Empire took place when the Young Turk movement forced Sultan Abdulhamid II to restore the Ottoman constitution of 1876 and ushered in multi-party politics within the Empire. From the Young Turk Revolution to the Empire's end marks the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire's history. More than three decades earlier, in 1876, constitutional monarchy had been established under Abdulhamid during a period of time known as the First Constitutional Era, which lasted for only two years before Abdulhamid suspended it and restored autocratic powers to himself.

| the Young Turk Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire | |||||||

Declaration of the Young Turk Revolution by the leaders of the Ottoman millets in 1908 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

.svg.png.webp) |

| Timeline |

| Historiography (Ghaza, Decline) |

With a Constitutionalist revolt in the Rumelian provinces instigated by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), Abdulhamid capitulated and announced the restoration of the Constitution. After an attempted monarchist counterrevolution in favor of Abdulhamid the following year, he was deposed and his brother Mehmed V ascended the throne.

Background

Countering the conservative politics of Abdulhamid's reign was the amount of social reform that occurred during this time period. The development of a more liberal environment in Turkey strengthened the culture, and also provided the grounds for the later rebellion. Abdulhamid's political circle was close-knit and ever-changing. When the sultan abandoned the previous politics from 1876, he suspended the Ottoman Parliament in 1878. This left a very small group of individuals able to partake in politics in the Ottoman Empire.[1]

The Young Turks

The origins of the revolution lie within the Young Turk movement, which contained two main factions: Liberals, and Unionists. What united them was opposition to Abdulhamid's regime, repromulgating the 1876 Constitution, and modernization however they disagreed about the Empire's future.[1]

The Liberals represented educated the upper-class groups in the Ottoman Empire and desired a more relaxed form of government with little economic interference. They also pushed for more autonomy of the different ethnic groups, which was popular among the minorities within in the empire.

In a slightly lower class formed a different group- the Unionists, with the preeminent organization being the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). Unionists, (many inspired by the Meiji Restoration) believed in a rapid modernization of the empire so it could stand up to European powers, as well as embracing ideas of nationalism and social Darwinism, and keeping the empire united. The CUP infiltrated many institutions within Abdulhamid's regime, with most recruits being young officers of the Ottoman Army.

Revolution

The event that triggered the Revolution was a meeting in the Baltic port of Reval between Edward VII of the United Kingdom and Nicholas II of Russia in June 1908. Though these imperial powers had experienced relatively few major conflicts between them over the previous hundred years, an underlying rivalry, otherwise known as "the Great Game", had exacerbated the situation to such an extent that resolution was sought. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 brought shaky British-Russian relations to the forefront by solidifying boundaries that identified their respective control in Persia (eastern border of the Empire) and Afghanistan.

The defense of their shrinking state had become a matter of intense professional pride within the military which caused them to raise arms against their state. Many Unionist officers of the Ottoman Third Army based in Salonika (modern Thessaloniki), feared that the meeting was a prelude to the partition of Macedonia and mutinied against Sultan Abdülhamid II. A desire to preserve the state, not destroy it, motivated the revolutionaries. The revolt began in July 1908.[2] Major Ahmed Niyazi, Ismael Enver, Eyub Sabri, and other Unionists within the Third Army fled into the mountains to organize guerilla bands of volunteers and deserters all the while pressuring Abdulhamid to reinstate the constitution. The rapid momentum of the Unionist's organization, intrigues within the military, and discontent with Abdulhamid's autocratic rule and a desire for the constitution meant Abdulhamid was alone and compelled to capitulate.

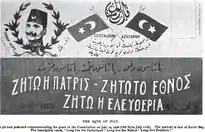

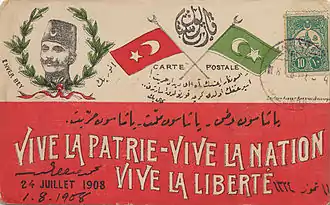

On 24 July, Abdulhamid II capitulated and announced restoration of the 1876 constitution, starting the Ottoman Empire's Second Constitution Era.[3] Importantly, the CUP did not overthrow the government and nominally committed itself to democratic ideals and constitutionalism. In reality however, power was shared between the palace (Abdulhamid) in Istanbul, the Ottoman Chamber of Deputies in Istanbul, and the CUP's Central Committee based in Salonika.

Aftermath

The 1908 Ottoman general election took place during November and December 1908. The candidates backed by the CUP won 60 seats in the parliament. The Senate of the Ottoman Empire reconvened for the first time in over 30 years on 17 December 1908 with the living members from the First Constitutional Era. The Chamber of Deputies' first session was on 30 January 1909. These developments caused the gradual creation of a new governing elite.

Following the revolution, many organizations, some of them previously underground, established political parties.[4] Among these the CUP and Freedom and Accord Party, also known as the Liberal Union or Liberal Entente (LU), were the major parties. There were smaller parties such as Ottoman Socialist Party. On the other end of the spectrum were the ethnic parties which included; People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section), Bulgarian Constitutional Clubs, Jewish Social Democratic Labour Party in Palestine (Poale Zion), Al-Fatat, and Armenians organized under Armenakan, Hunchakian and Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF).

While the Young Turk Revolution had promised organizational improvement, once instituted, the government at first proved itself rather disorganized and ineffectual. Although these working-class citizens had little knowledge of how to control a government, they imposed their ideas on the Ottoman Empire. In a small Liberal victory, Kâmil Pasha, a Liberal supporter and ally to England, was appointed as the Grand Vizier on 5 August 1908. His policies helped to maintain some balance between the Committee of Union and Progress and the Liberals, but conflict with the former led to his removal barely 6 months later, on 14 February 1909.[5]

The Abdulhamid maintained his throne by conceding its existence as a symbolic position, but in April 1909 attempted to seize power (Ottoman countercoup of 1909) by stirring populist sentiment throughout the Empire. The Sultan's bid for a return to power gained traction when he promised to restore the caliphate, eliminate secular policies, and restore the sharia-based legal system. On 13 April 1909, army units revolted, joined by masses of theological students and turbaned clerics shouting, "We want Sharia", and moving to restore the Sultan's absolute power. The 31 March Incident, on 24 April 1909 reversed the actions and restored the parliament by the Army of Action commanded by Mahmud Shevket Pasha. The deposition of Abdulhamid II in favor of Mehmed V followed.

To European powers, took advantage of the chaos by decreasing Ottoman sovereignty in the Balkans. Bulgaria, de jure an Ottoman vassal but de facto all but formally independent, declared its independence on the 5th of October. The day after, Austria-Hungary officially annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina which used to be de jure Ottoman territory but de facto occupied by Austria-Hungary.

Cultural and International Impact

In some communities, such as the Jewish (cf. Jews in Islamic Europe and North Africa and Jews in Turkey), reformist groups emulating the Young Turks ousted the conservative ruling elite and replaced them with a new reformist one.

Armenian Revolutionary Federation, previously outlawed, became the main representative of the Armenian community in the Ottoman Empire,[6] replacing the pre-1908 Armenian elite, which had been composed of merchants, artisans, and clerics.

The revolution and CUP's work had a great impact on Muslims in other countries. The Persian community in Istanbul founded the Iranian Union and Progress Committee. Indian Muslims imitated the CUP oath administered to recruits of the organisation. The leaders of the Young Bukhara movement were deeply influenced by the Young Turk Revolution, and saw it as an example to emulate.

In the 2010 alternate history novel Behemoth by Scott Westerfeld, the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 fails, igniting a new revolution at the start of World War I.

It has been said the Young Turk Revolution has been overshadowed by other revolutions of the time, including the 1917 Russian Revolution and the 1911 Xinhai Revolution.

See also

Bibliography

- Der Matossian, Bedross (2014). Shattered Dreams of Revolution: From Liberty to Violence in the Late Ottoman Empire. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-9263-9.

- Unal, Hasan. "Ottoman policy during the Bulgarian independence crisis, 1908–9: Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria at the outset of the Young Turk revolution." Middle Eastern Studies 34.4 (1998): 135-176.

- Lévy-Aksu, Noémi, and François Georgeon. The Young Turk Revolution and the Ottoman Empire: The Aftermath of 1908 (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017).

- Erickson, Edward (2013). Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137362209.

- Hanioğlu, M Şükrü (2001), Preparation for a Revolution: The Young Turks, 1902–1908, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513463-X.

- Benbassa, Esther (1990), Un grand rabbin sepharde en politique, 1892‐1923 [A great sephardic Rabbi in politics, 1892–1923] (in French), Paris, pp. 27–28.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Young Turk Revolution. |

- Christian Rakovsky, The Turkish Revolution, August 1908

- Zürcher, Erik Jan. "Young Turk Governance in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War." Middle Eastern Studies 55.6 (2019): 897-913 online.

- Zürcher, Erik Jan. "The Young Turk revolution: comparisons and connections." Middle Eastern Studies 55.4 (2019): 481-498 online.

References

- Ahmad, Feroz (July 1968). "The Young Turk Revolution". Journal of Contemporary History. 3 (3): 19–36. doi:10.1177/002200946800300302. JSTOR 259696. S2CID 150443567.

- The Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Edition, 1983, page 788, Volume 13

- Quataert, Donald (July 1979). "The 1908 Young Turk Revolution: Old and New Approaches". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 13 (1): 22–29. doi:10.1017/S002631840000691X. JSTOR 41890046.

- (Erickson 2013, p. 32)

- Somel, Selçuk Akşin (2003). Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire. The Scarecrow Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-8108-4332-3.

- Zapotoczny, Walter S. "The Influence of the Young Turks" (PDF). W zap online. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2011.