Yaqui Uprising

The Yaqui Uprising, also called the Nogales Uprising, was an armed conflict that took place in the Mexican state of Sonora and the American state of Arizona over several days in August 1896. In February, the Mexican revolutionary Lauro Aguirre drafted a plan to overthrow the government of President Porfirio Díaz. Aguirre's cause appealed to the local Native Americans, such as the Yaqui, who organized an expedition to capture the customs house in the border town of Nogales on August 12.

| Yaqui Uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Yaqui Wars | |||||||

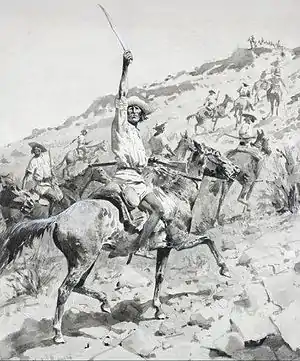

Uprising of the Yaqui Indians - Yaqui Warriors in Retreat, by Frederic Remington. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Mexican Revolutionaries | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Teresa Urrea Lauro Aguirre Tomas Urrea | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~3 killed | |||||||

During the battle that followed, several people were killed or wounded and the rebels were ultimately forced to retreat, ending the conflict after one encounter. It is notable for being one of the final episodes of the American Indian Wars, and for having involved simultaneous participation from American militia and Buffalo Soldiers, Mexican infantry, and local police, all of whom participated in an inconclusive pursuit of the hostiles.[1]

Background

The conflict stemmed from resistance to dictator Porfirio Díaz and his "anti-agrarian and anti-indigenous Mexican policies". It was propagated by the fact that the Mexican Army and the Yaquis had been fighting a largely uninterrupted war against one another for several decades prior to 1896. The war forced many of the natives to flee north into the U.S. state of Arizona, where they settled around Tucson and Phoenix, occasionally recrossing the border to fight the Mexican soldiers. Díaz was known for censoring his critics in the media, which created unrest among the civilian population of Mexico and in the United States.

At the town of Solomonville, in southern Arizona, journalist Lauro Aguirre and Flores Chapa established the anti-Díaz newspaper El Independiente, and on February 5, 1896, they wrote the Plan Restaurador de Constitucion y Reformista. The plan claimed that Díaz had violated the Constitution of 1857 in multiple ways and was mistreating native Mexicans, particularly by deporting them to the Yucatán. It also proposed free elections and the use of force to overthrow the Díaz regime. The Yaqui and the Pima were long-time enemies of Mexico, so Aguirre had no trouble in recruiting local natives to support his cause.

Uprising

In March 1896, the United States government arrested Aguirre and Chapa because the Mexican consul accused them of conspiring to re-enter Mexico and engage in revolutionary actions, but both of the men were acquitted in federal court after the American consul's investigation concluded that they were innocent of any wrongdoing. However, the plan was signed by twenty-three people, including Aguirre, and one other man believed to be Tomas Urrea, the father of the revolutionary Teresa Urrea. Because Tomas Urrea had close relations with many of the people involved in the uprising, Teresa Urrea was suspected of being the mastermind. Sixty to seventy Yaqui, Pima and Mexican revolutionaries, many of them employees of the Southern Pacific Railroad, united in a rebel band calling themselves "Teresitas" to participate in a raid, with the goal being to "capture the arms, ammunition, and money in the Mexican custom-house at Nogales."[1][2][3][4][5]

Nogales, Sonora, and Nogales, Arizona are immediately opposite each other on the U.S.–Mexico border, so on August 12, when the Teresitas attacked, the Mexican consulate, Manuel Mascarena, requested aid from the Americans in or around the American Nogales. A militia was hastily assembled on the Arizona side of the border and sent in to help rout the rebels during the battle. On the next day Brigadier General Frank Wheaton dispatched elements of the 24th Infantry. At least three men were killed in the fighting and several others were wounded, but other sources claim that seven Mexicans died while the Teresitas lost about the same amount. When the rebels retreated they were pursued by a posse of Sonoran policemen. The police eventually caught up with the Teresitas later that day and fought another skirmish which left the Mexican commander dead. On the day after that, a large force of Mexican Army troops, under the command of Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky, joined in the pursuit while two companies of the 24th Infantry conducted their own separate operations. Both of the pursuing parties failed to catch up with the rebels, a portion of whom dispersed to their homes in southern Arizona. After that there was no further conflict, and the successful defense of Nogales was effective in suppressing the uprising.

Aftermath

Aguirre continued to print and circulate news critical of the Díaz regime but in 1902 he was forced to leave his home in Mexico out of fear that Díaz was trying to kidnap him. Aguirre continued writing in the United States and later attempted to take over the city of Ciudad Juárez, but this plot was foiled. On September 11, 1896, Teresa Urrea publicly denied having had anything to do with the uprising, but Porfirio Díaz held her responsible so he pressured the American government into moving Urrea from El Paso, Texas to Clifton, Arizona, away from the volatile border region.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

See also

References

- Johnson, pg. 664-665

- Garcia, pg. 173-176

- Ruiz, pg. 97-117

- URREA, TERESA | The Handbook of Texas Online| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)

- Garza, pg. 40-41

- Huachuca Illustrated, vol 1, 1993: Fort Huachuca: The Traditional Home of the Buffalo Soldier

- Garcia, Mario T. (1981). Desert Immigrants: The Mexicans of El Paso, 1880-1920. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02520-3.

- Ruiz, Vicki; Virginia Sánchez Korrol (2005). Latina legacies: identity, biography, and community. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515399-5.

- Johnson, Alfred S.; Clarence A. Bickford (1896). The Cyclopedic review of current history, Volume 6. Garretson, Cox & Co.

- Garza, Hedda (1994). Latinas: Hispanic women in the United States. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2360-X.

_troops_return_colors_to_Union_League_Club._Men_draw_._._._-_NARA_-_533590.tif.jpg.webp)