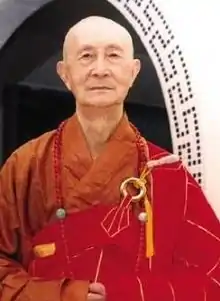

Yin Shun

(Master) Yin Shun (印順導師, Yìnshùn Dǎoshī) (5 April 1906 – 4 June 2005) was a well-known Buddhist monk and scholar in the tradition of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism. Though he was particularly trained in the Three Treatise school, he was an advocate of the One Vehicle (or Ekayana) as the ultimate and universal perspective of Buddhahood for all, and as such included all schools of Buddha Dharma, including the Five Vehicles and the Three Vehicles, within the meaning of the Mahayana as the One Vehicle.[2] Yin Shun's research helped bring forth the ideal of "Humanistic" (human-realm) Buddhism, a leading mainstream Buddhist philosophy studied and upheld by many practitioners.[3] His work also regenerated the interests in the long-ignored Āgamas among Chinese Buddhist society and his ideas are echoed by Theravadin teacher Bhikkhu Bodhi. As a contemporary master, he was most popularly known as the mentor of Cheng Yen (Pinyin: Zhengyan), the founder of Tzu-Chi Buddhist Foundation, as well as the teacher to several other prominent monastics.

Yin Shun 印順 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Venerable Master |

| Other names | Sheng Zheng(盛正) |

| Personal | |

| Born | Zhang Luqin April 5, 1906 Zhejiang Province, Qing Dynasty |

| Died | June 4, 2005 (aged 99) Hualien County, Republic of China |

| Religion | Mahayana Buddhism |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Other names | Sheng Zheng(盛正) |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Taixu (太虛), Qingnian (清念)[1] |

Although Master Yin Shun is closely associated with the Tzu-Chi Foundation, he has had a decisive influence on others of the new generation of Buddhist monks such as Sheng-yen of Dharma Drum Mountain and Hsing Yun of Fo Guang Shan, who are active in humanitarian aid, social work, environmentalism and academic research as well. He is considered to be one of the most influential figures of Taiwanese Buddhism, having influenced many of the leading Buddhist figures in modern Taiwan.

Biography

Yin Shun was born on 5 April 1906 (The traditional Chinese calendar: March 12, 丙午) in a village in Zhejiang Province, China. His birth name was Zhang Luqin (Wade–Giles: Chang Luch'in). At the time of Zhang's birth, it was the end of the Qing Dynasty. Eleven days after his birth, Zhang was critically ill and nearly died. He began school at age seven.

In his studies, he stumbled upon the subject of immortality—a subject that Zhang found interesting. His parents found what Zhang was doing to be very unusual, so they required him to teach at other schools.

Zhang turned his attention to Confucianism and Taoism, but neither of their philosophies could help him find the truth. At one point, Christianity sparked light into his heart. However, Zhang still felt empty, and could not commit himself to Christianity after two years. One day, Zhang was looking for something to read. He stumbled onto the words "the Buddha Dharma". This immediately sparked interest into his heart again, like what Christianity did for him, and Zhang zealously looked for anything that had to do with Buddhism.

Becoming a monastic

Searching for the Dharma

In 1930, Zhang applied to a Buddhist college in Beijing. For many days he had traveled from his home to Beijing, with high hopes. He arrived too late for acceptance.

While pondering where he could go next, Zhang thought of a temple called "Tiantong Temple". Zhang then went to Mount Putuo, where he met a young man named Wang. Both searched for an abode where they could study the Buddha Dharma. They eventually found a small place where they could do so, where their abbot who was well cultivated. They asked to study under him.

The elder monk then referred Zhang and Wang to another place called Fuzhun Monastery (福泉庵), less than a half mile from where they were. The two hurried to Fuzhun Monastery. Later, on October 11, 1930, the abbot, Master Qingnian (清念和尚), shaved Zhang Luqin's head and gave him the Dharma name of Yin Shun (印順).

Three Systems of Mahayana

Master Taixu 太虛 (1890–1947) divided Mahayana Buddhism into three types. They are: School of śūnyatā and prajña (faxing konghui zong 法性空慧宗, Madhyamaka), School of dharmalaksana and vijnaptimatra (faxiang weishi zong 法相唯識宗) and School of dharma-dhatu and perfect enlightenment (fajie yuanjue zong 法界圓覺宗). Furthermore, he states that dharma-dhatu is on the highest level, complete and the final dharma. On the following levels are Madhyamaka and Vijnaptimatra.

By contrast, Yinshun 印順 (1906–2005), Tiaxu’s disciple, took a different direction from that of his teacher. He claims that Mahayana Buddhism can be divided into three systems. They are: School of śūnyatā and name only (xingkong 性空唯名系, Madhyamaka), School of illusion and Vijñapti-mātra (weishi 虛妄唯識系, Vijñapti-mātra) and School of genuine and permanent mind (zhenchang 真常唯心系, Tathāgata-garbha).

For him, early Mahayana Buddhism is characterized by Nāgārjuna’s 龍樹 prajñapāramitā thought. Mahayana Buddhism, in its middle stage, is characterized by Vijñapti-mātra which was upheld by Asanga and Vasubandhu. Later Mahayana Buddhism is mainly characterized by Tathāgata-garbha thought 如來藏思想. Therefore, it is clear that Yinshun distanced himself from his teacher’s position.[4]

Achievements

In March 2004, he was awarded the Order of Propitious Clouds Second Class, for his contributions to the revitalization of Buddhism in Taiwan.[5]

Encounter with Master Cheng Yen

On February 1963, a thirty-two-day novitiate for Buddhist monks and nuns was held in Taipei. Monks and nuns came from all over Taiwan to register. All were accepted except a young female devotee from Hualien, a county in eastern Taiwan.

Master Yin Shun recalled the day he first met Master Cheng Yen:[6]

Huiyin, a student of mine, brought her to the Hui Ri Lecture Hall, where I lived, to purchase The Complete Teachings of Master Taixu. Huiyin told me that the woman had been rejected from the novitiate because she had shaved her own head and her teacher was a layman. Someone said she could have just asked any of the monks or nuns present to accept her as a disciple, but she claimed that she needed to seek her master carefully. After she bought the book, there was a heavy rain shower and she couldn't leave. She then begged Huiyin to tell me that she wished to become my disciple. She had no idea that I rarely accept disciples¹. As if the heavens had heard her wish, I happened to walk out of my room just then. Huiyin came toward me and told me what was going on. I couldn't figure out why she chose me as her master, but I consented.

¹At the time, Yin Shun only had three disciples. All three now are teaching the Buddha Dharma in the United States.

Master Yin Shun then said to her, "Our karmic relationship is very special. As a nun, you must always be committed to Buddhism and to all living beings."

Since the registration for the novitiate was about to end within the hour, the venerable master quickly gave the young disciple her Buddhist name, Cheng Yen, and told her to get going and begin the novitiate promptly. At that moment, the conditions for the creation of the Tzu-Chi Foundation began.

In the summer of 1979, Master Yin Shun came to Hualien. Living in this beautiful but undeveloped part of the island, Cheng Yen told Master Yin Shun about her aspiration to build a high-quality hospital for the people living in eastern Taiwan, where there were few medical facilities.

As he listened to her, he could foresee the daunting challenges lying ahead. Like a father sharing his life experiences with his daughter, he said, "Just like the time you told me you intended to begin charity work, I reminded you to think whether you would have the strength and the money when more people came to you for help. The task can only be realized with unwavering commitment."

Seeing his disciple's resolution, Master Yin Shun's mind was put at ease. With this talk, the hospital construction project began. Although Cheng Yen would soon face many insurmountable difficulties and challenges, Master Yin Shun's support gave Cheng Yen the strength to go on. He transferred virtually all the monetary offerings made to him by his followers to the hospital construction. The sum accumulated throughout the years was truly sizable.

Death and funeral

On June 4, 2005, Master Yin Shun died after fighting pulmonary tuberculosis since 1954.[7] He died in Tzu-Chi hospital in Hualien at the age of 100.[8] In Taiwan, many were stunned to hear of his death, even though his death was expected in the coming months. Tzu-Chi, along with other Buddhist organizations and monasteries influenced by Yin Shun, joined in mourning for eight days, the length of his funeral.

Among those attending the services were Taiwanese President Chen Shui-bian, ROC Premier Frank Hsieh, and other legislators.[9] Several monastics from many parts of the world, predominantly the United States, also attended Master Yin Shun's funeral. Monastics who were disciples of Master Yin Shun also attended the funeral, including Master Cheng Yen herself.

Master Yin Shun had a simple and spartan lifestyle in the last days of his life, so his disciples decided to keep his funeral simple but solemn. His funeral was held at Fu Yan Vihara in Hsinchu, where he had lived for many years until his death. Master Yin Shun was later cremated on June 10 and his ashes and his portrait used during the services were placed inside a hall alongside the remains of other monastics.

Works

- The Way To Buddhahood: Instructions From A Modern Chinese Master, Boston: Wisdom Books, 1998

- "Selected Translations of Miao Yun" (PDF). Archived from the original on May 28, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link), Buddha Dharma Education Association 1995. This a translation of selections of Sublime Clouds Collection 《妙雲集》, a major collection of Yin Shun's writings.

- A Sixty-Year Spiritual Voyage on the Ocean of Dharma, Noble Path Buddhist Education Fellowship, 2009. Translation of Yun Shun's autobiography 《游心法海六十年》 by Yu-Jung L. Avis, Po-Hui Chang, and Maxwell E. Siegel.

- An Investigation into Emptiness: Parts One and Two, Towaco, NJ: Noble Path Buddhist Education Fellowship Incorporated, 2017. Translation of 《空之探究》 by Shi Hui Feng.

- Over 50 works in Chinese Mandarin, on a range of issues, covering many thousands of pages. These are presently in the process of translation into English.

References

- "印順法師─教證得增上,聖道耀東南".

1930年,在福泉庵禮清念和尚為師,落髮出家...回佛頂山閱藏三年餘,期間曾奉太虛之函,往閩南佛學院授課。

- See page 357 of The Way To Buddhahood: Instructions From A Modern Chinese Master

- Zheng Xin's Guide

- Wong, L.C. (2013). "From the Vijñapti-mātra Thoughts of Dharmapāla 's lineage translated by Master Xuanzang to the Maitreya Studies in Modern Greater China". First International Academic Forum on Maitreya Studies. Hong Kong: Institute of Maitreya Studies.

- Carsten Storm; Mark Harrison, eds. (2007). The Margins of Becoming: Identity and Culture in Taiwan. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 85. ISBN 978-3-447-05454-6 – via Google Books.

On the 5th of March 2004, only two weeks before the 2004 presidential election, CHEN SHUIBIAN 陳水扁 awarded the monk YINSHUN the er deng qing yun xun zhang 二等卿雲勳章 (Second-Class Order of Propitious Clouds).

- 潘, 煊 (2005). 法影一世紀. Taiwan: 天下文化出版社. ISBN 986-417-475-4.

- O'Neill, Mark (2010). Tzu Chi: Serving with Compassion. John Wiley & Sons. p. 182. ISBN 9780470825679.

- "Buddhist master Yin Shun dies at 100". Taipei Times. June 5, 2005. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- "President, premier pay last respects to Yin Shun". Taipei Times. June 11, 2005. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

Bibliography

- Bingenheimer, Marcus (2004), Der Mönchsgelehrte Yinshun (*1906) und seine Bedeutung für den Chinesisch-Taiwanischen Buddhismus im 20. Jahrhundert. [The Scholar Monk Yinshun 印順 – His Relevance for the Development of Chinese and Taiwanese Buddhism.] (PDF), Heidelberg: Edition Forum (Würzburger Sinologische Schriften), ISBN 3-927943-26-6, archived from the original on June 23, 2014, retrieved April 21, 2013CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Bingenheimer, Marcus (2007)."Some Remarks on the Usage of Renjian Fojiao 人間佛教 and the Contribution of Venerable Yinshun to Chinese Buddhist Modernism" (PDF). Archived from the original on June 23, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2012.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) In: Development and Practice of Humanitarian Buddhism: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Mutsu Hsu, Jinhua Chen, and Lori Meeks (Eds.). Hua-lien (Taiwan): Tzuchi University Press, pp. 141–161.

- Bingenheimer, Marcus (2009)."Writing History of Buddhist Thought in the Twentieth Century: Yinshun (1906–2005) in the Context of Chinese Buddhist Historiography". Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) Journal of Global Buddhism Vol.10, pp. 255–290. ISSN 1527-6457.

- Hurley, Scott (2001). A study of Master Yinshun's hermeneutics: An interpretation of the tathagatagarbha doctrine, PhD Thesis, University of Arizona

- Hurley, Scott (2004). The Doctrinal Transformation of 20th Century Chinese Buddhism: Master Yinshun's interpretation of the tathagatagarbha doctrine at the Wayback Machine (archived June 1, 2014), Contemporary Buddhism 5 (1), 29–46

- Pan, Shuen (2002). The Story of Dharma Master Yin Shun. Tzu Chi Quarterly Summer 2002: Translated by Teresa Chang and Adrian Yiu.

- Travagnin, Stefania (2004). Master Yinshun and the Pure Land Thought: A Doctrinal Gap Between Indian Buddhism and Chinese Buddhism. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 57 (3), 271–328

External links

- Yin Shun Foundation

- yinshun.org, Chinese language site

- Buddhism discussion group A on-line discussion group concentrated on Master Yin-Shun's books.

- Pu Ti Guang Classroom A classroom dedicated to Master Yin-Shun's teachings.