13th Cavalry Regiment

The 13th Cavalry Regiment ("13th Horse"[1]) is a unit of the United States Army. The 2nd Squadron is currently stationed at Fort Bliss, Texas, as part of the 3rd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division.

| 13th Cavalry Regiment | |

|---|---|

13th Cavalry Regiment coat of arms | |

| Active | 1901–present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Cavalry and armor |

| Size | Regiment |

| Nickname(s) | 13th Horse (special designation)[1] |

| Motto(s) | "It Shall Be Done" |

| Engagements | Philippine–American War

|

| Decorations | Meritorious Unit Commendation |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia |  |

U.S. Cavalry Regiments | |

|---|---|

| Previous | Next |

| 12th Cavalry Regiment | 14th Cavalry Regiment |

_in_1915.jpg.webp)

History

The 13th Cavalry Regiment was first constituted on 2 February 1901 in the Regular Army, and its first active component was K Troop. The Regiment was organized on 26 July 1901 at Fort Meade, South Dakota. Immediately following the American takeover of the Philippines after the Spanish–American War in 1898, Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo led a rebellion against American rule and the Philippine–American War erupted in 1899. By 1902, Aguinaldo had sworn allegiance to the United States and the war was officially declared to be over, but insurgents still plagued the countryside, prompting the deployment of the 13th Cavalry Regiment to the Philippine Islands. From 1903 to 1905 the 13th Cavalry conducted counter-insurgency operations against Filipino rebels and bandits until their return to the United States. In 1909 they returned to the Philippines and continued to conduct counter-insurgency operations until 1910.[2]

Border War

In 1911, the 13th Cavalry Regiment’s Headquarters was moved to Fort Riley, Kansas, but their attention quickly shifted to defending the Mexico–United States border. From 1911 to 1916 the 13th Cavalry patrolled the desert landscape of the border on horseback, deterring bandito raids and protecting American border towns from the violence seeping over from the ongoing Mexican Revolution. One such instance was the hunt for the infamous Mexican outlaw Pascual Orozco. He was placed under house-arrest in El Paso, Texas for violating US neutrality laws, but managed to escape. A posse consisting of 8 local deputies, 13 Texas Rangers, and 26 Troopers of the 13th Cavalry was formed to pursue him. Orozco managed to steal a herd of horses until the posse caught up to him and his gang at High Lonesome in the Van Horn Mountains and killed them in a gunfight.

Raid on Columbus, NM

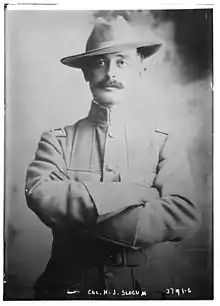

Under the command of COL Herbert Jermain Slocum, four Troops and a Machine-Gun Troop of the 13th Cavalry were posted at “Cavalry Camp” in Columbus, New Mexico when raiders under Mexican Revolutionary Pancho Villa attacked across the border in the dead of night on 9 March 1916.[3] Most of the garrison was asleep when the raiders entered Columbus from the west and southeast shouting "¡Viva Villa! ¡Viva México!" and other phrases. The Cavalrymen awoke to an army of 600 Villistas burning the city and looting the homes. Despite being taken by surprise, the Troopers quickly recovered. Even the cooks, already up and working on breakfast for the Troopers, fought back, throwing boiling water at the attackers. Soon after the attack began, 2LT John P. Lucas, commanding the 13th Cavalry's Machine-Gun Troop, made his way barefooted from his quarters to the camp's barracks. He organized a hasty defense around the camp's guard tent, where his machine-guns were kept under lock, with two men and a Hotchkiss M1909 machine-gun. He was soon joined by the remainder of his unit and 30 Troopers armed with M1903 Springfield rifles led by 2LT Horace Stringfellow, Jr. The Troop's four machine-guns fired more than 5,000 rounds apiece during the fight, their targets illuminated by fires of burning buildings.[3]

The battle raged until a Mexican bugler sounded the retreat after 90 minutes of fighting, and rode away to the south. 8 Cavalry Troopers were killed and 8 were wounded in this raid, but their tenacious defense inflicted over 100 enemy casualties. MAJ Frank Tompkins, commanding the Regiment's 3rd Squadron and acting as its Executive Officer, asked and received permission from COL Slocum to pursue the withdrawing Mexicans. He led two Troops 15 miles into Mexico in pursuit of a force approximately six times the size of his, engaged Villa's rearguard four times, and inflicted some losses on them before withdrawing back across the border after running low on ammunition and water. MAJ Tompkins was awarded the Army Distinguished Service Medal and the Distinguished Service Cross in 1918 for this action.[4]

Punitive Expedition

Pancho Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico on 9 March 1916 was a casus belli in the eyes of US President Woodrow Wilson, and he ordered General John "Black Jack" Pershing to lead a Punitive Expedition into Mexico on 16 March 1916. Four cavalry regiments, two infantry regiments, and two batteries of artillery formed the main body of the expedition, and the 13th Cavalry was in the vanguard, taking point for the expedition.[4]

In early April 1916, MAJ Frank Tompkins, who fought in the Battle of Columbus, persuaded GEN Pershing to allow him to lead 8 officers and 120 men of Troops K and M, 13th Cavalry, on a raid deep into Mexican territory. MAJ Tompkins' intentions were to chase and eventually engage the elusive rebels of Pancho Villa. After preparations were completed, the force left camp on 5 April. The Americans made a quick ride across the Mexican desert, traveling 85 miles in 50 hours. Following several days in the wilderness, MAJ Tompkins wrote; "We were ragged, shoes were gone and nearly everyone had a beard. We certainly presented a hard-boiled, savage appearance." The Americans were hoping to rest at the city of Parral for a day, and they were told they'd be welcome by a Carrancista (Mexican Constitutionalist) officer along the way. However, when the column arrived at Parral in the early morning of 12 April, the Carrancista commander of the city, General Ismael Lozano, informed MAJ Tompkins that coming to the city was a bad idea and that he must leave immediately. Tompkins agreed so the Americans left Parral not long after getting there.[3]

On the way out of town, a group of Mexicans began shouting "Viva Villa", and other phrases, so MAJ Tompkins shouted the same back. A few minutes later, as the column was just outside town, a cavalry force of about 550 Carrancistas launched an attack on the American column. MAJ Tompkins had been betrayed. Within the first few shots a Sergeant standing next to Tompkins was hit and killed while a second man was seriously wounded. Heavily outnumbered, the 13th Cavalry had no choice but to keep going so they dismounted a rear guard to take up positions on a small hill and engage the pursuing Mexicans. In this first skirmish, an estimated 25 Mexicans were killed and the rest were driven off. The rear guard then regrouped with the main force where they withstood another attack. During the second skirmish, an estimated 45 Mexicans were killed. The Troopers continued their ride to Santa Cruz de Villegas, a fortified town, 8 miles from Parral, that the Americans could defend. The Cavalry reached their town, but the Mexicans were not far away, and MAJ Tompkins was facing the possibility of his 100-man force being besieged by hundreds of Carrancistas, so he sent out dispatch riders for reinforcements.

Just before 0800, a force of Buffalo Soldiers from the 10th Cavalry, arrived. They had recently engaged about 150 Villistas at the Battle of Agua Caliente on 1 April . Following the arrival of reinforcements, the Mexicans retreated back to Parral and there was no more fighting. Two Americans were killed in the battle and six others were wounded, including MAJ Tompkins. The enemy, however, suffered much greater losses.[5] The Battle of Parral was a turning point in the Mexican Expedition, it marked America's furthest penetration into Mexico during the operation, 516 miles from the border, and marked the beginning of a slow withdrawal from Mexico which ended in early 1917. When General Pershing heard of the Carrancista government's betrayal, he was "mad as hell" and demanded a formal apology, but it never came. The 13th Cavalry Regiment's exceptional performance in America's last great mounted cavalry campaign earned it the special designation; 13th Horse.[3]

Interbellum

The period between the Mexican Expedition and World War II was a tumultuous time for the 13th Cavalry. The United States entered World War I in April 1917, but the Regiment remained on the Mexican border and patrolled the area to protect against future raids. In 1921 it returned to Fort Riley, Kansas where it was key in developing the Army's future mechanized and armored force. The Troopers received M1 Combat Cars for their reconnaissance roles, but some remained mounted on horseback. In 1933, it was assigned to the 2nd Cavalry Division, and was soon transferred to the 7th Cavalry Brigade (Mechanized) at Fort Knox, Kentucky in 1936. Here, the troopers dismounted their loyal horses for the final time and went on to become a fully mechanized unit.

The 13th Cavalry, in their new vehicles, was sent to Pine Camp, New York to participate in some of the Army’s first ever mechanized warfare exercises. This training helped to identify the advantages and shortcomings of the Army’s new mechanized cavalry forces, and the 13th Cavalry played a major role in the Army’s modernization. On 15 June 1940, the 13th Cavalry Regiment was redesignated as the 13th Armored Regiment (Light) and was assigned to the newly formed 1st Armored Division. As a Light Armored Regiment, the 13th had an authorized complement of 91 Officers and 1,405 Enlisted Men, along with 82 M3 Scout Cars for reconnaissance, and 136 M3 Stuart Light Tanks.[6] With the 1st AD, the 13th Armor (Light) participated in the Arkansas, Louisiana, and Carolina Maneuvers of 1941, which were the Army’s first training exercises in large-scale armored warfare.

These maneuvers helped the Army’s fledgling mechanized force identify its strengths and weaknesses, and helped the Army develop new strategies and tactics regarding the implementation of armored units, and how to coordinate between reconnaissance, armor, infantry, and artillery for combined arms maneuver. In this regard, the 13th Armored Regiment (Light) was a true pioneer in the development of the US Army's Armor Branch. On 7 December 1941, the Regiment was redesignated as the 13th Armored Regiment after it received larger tanks and underwent a significant reorganization; 1st Battalion consisted of the M3 Stuart light tanks and was used in a reconnaissance and security role. 2nd and 3rd Battalions consisted of M3 Lee medium tanks for use in direct action.

That same day, 7 December 1941, the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, thrusting the United States into World War II. On 11 December, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy declared war on the United States as well, thus setting the stage for America's involvement in a two-front war. The men of the 13th Armored Regiment would not have long to wait until they could test their newfound skills as an armored force in battle. [3]

World War II

The 1st Armored Division was one of the first American units to sail across the Atlantic to do battle with the Axis. Leaving from Fort Dix, New Jersey on 11 April 1942, the Old Ironsides patch set foot on European soil in Northern Ireland on 16 May 1942. Here, they trained with a new intensity as they prepared to go into battle for the first time.

Algeria-French Morocco

On 8 November 1942, almost a full year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Allied American, Free French, and British armies launched Operation Torch, the seaborne invasion of French North Africa. The 13th Armored Regiment was assigned to the 1st Armored Division's Combat Command B, or CCB, and was split between “Task Force Red” and “Task Force Green” for the invasion. At this time, the commander of the 13th Armored Regiment was COL Paul McDonald Robinett. Standing at five feet four, he was known to his men as “Little Napoleon,” “Little Caesar,” or “Robbie.” A cavalryman at heart, he was on the United States Olympic Equestrian Team and studied at the French Cavalry School at Saumur. He offered a dollar to any Soldier who could out-shoot him, and only one man ever collected.[7]

The M3 Lee tanks were too large for the US and British naval landing craft, so the initial armored elements would be limited to M3 Stuart light tanks and lighter vehicles. 1-13 Armor, under LTC John H. Todd, was ordered to land just west of Oran in Algeria, with the objective of forming a flying column to seize Lourmel Airfield before French planes could take off, then drive east toward La Sénia airfield. However, France's collaborationist government, Vichy France, was determined to resist the Allied invasion in order to save their country from further German retribution.

As part of TF Green, 1LT Richard Van Nostrand’s 1st Platoon, 13th AR Reconnaissance Company was the first to land. They began racing for their objectives at 0603. To the west, the remainder of 13th Armor Reconnaissance Company under CPT G. Samuel Yeiter, was the first unit to land as part of TF Red. Despite struggling through the soft sand on the beachhead, their Jeeps and M3 half-tracks began rolling to their objectives by 0820. By 0900, 1LT Van Nostrand’s Platoon received the 1st Armored Division’s first hostile fire from French snipers.[8] Soon after, the remainder of the flying column landed with M3 Stuart tanks and pressed on their objectives. Lourmel was secured by 1-13 Armor, and LTC Todd pushed east, breaking through a French roadblock. By the end of the day, 2-13 Armor’s tanks were being unloaded at the newly captured docks at Arzew. Attacking towards La Sénia near Oran, TF Green was halted by the French at Misserghin, seven miles from the airfield. A frontal attack by tanks and artillery was thwarted, and a flanking attack was tried, but this failed as well. One tank was knocked out on the road, forming a partial roadblock, and slowing Task Force Green’s advance. The strongpoint was eventually bypassed in the middle of the night, but the 13th Armor had learned valuable lessons in this battle. Its lack of infantry support made attacking anti-tank guns costly.[8] These lessons shaped how the 1st Armored Division would fight in the future.

Despite stronger than expected Vichy French resistance to the American landings, nothing could stop the 1st Armored Division, and the 13th Armored Regiment entered the city of Oran two days after landing. Two M3 Lee tanks from 2-13 Armor led the way into the city. An enemy shell struck one and disabled it, but the following tanks bypassed the position and pressed into the city. At this point, many of the Vichy French soldiers joined the Free French and the Allied cause, and the Vichy government was dissolved by the Germans.[8] The Vichy soldiers fought halfheartedly against an erstwhile enemy they didn't hate, but the 13th Armored Regiment's next enemy would not be so easy.

Tunisia

After Vichy French forces ceased resistance to the Allied landings of Operation Torch, the 1st Armored Division pushed east into Tunisia where they would meet a tougher enemy. The German Afrika Korps was a battle-hardened force which had been fighting the British and Free French armies in the deserts of North Africa for several years. When the tanks of the 13th Armored Regiment encountered them, they were some of the first American troops to encounter Panzer Mark IVs. From 1-4 December 1942, the 10th Panzer Division attacked positions occupied by the 13th Armor near Djedeida and Tebourba in Tunisia. In a valiant effort, tanks from Companies E and F, 2-13 Armor, sortied against the attacking Germans, but were stopped with many casualties and 7 tanks lost. During this action, PVT Casimir Gajek, E Co, earned the Distinguished Service Cross for carrying his wounded NCO, SGT Evans, out of a burning tank, and remaining with him under fire until medics could arrive. 1-13 Armor’s light tanks made a similar daylight charge on 10 December but were defeated by the heavier Panzers. The experienced Germans were not impressed with American tank tactics but noted that the tankers of the 1st Armored Division made up for their flaws with bravery. After withdrawing on 11 December 1st AD concluded that its M3 Stuart tanks were too light for modern warfare and began replacing them with heavier tanks.[8][9]

A series of counterattacks steadily pushed the Germans back towards Tunis, the final Allied objective in Tunisia, and the 13th Armor did well in several smaller tank battles in the desert. The year of 1943 began well for the 1st AD, but the Germans were not finished yet. In February 1943, Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel led a German combined-arms attack against the American and British positions known as the Battle of Kasserine Pass. Their superior maneuver and weaponry defeated elements of the 13th Armor and forced the Americans back over 50 miles before they rallied and halted the enemy offensive. Despite being forced from their positions, 2nd Battalion 13th Armored Regiment made a stand at the town of Sbeitla in the face of the German advance. G Company, 3-13 under CPT Herman T. McWatters covered the withdrawal of CCA along the Faïd-Sbeitla road, until they could be relieved by the rest of LTC Ben Crosby's 3rd Battalion. From their positions, their forward elements spotted a German armored column headed west towards the positions of 2nd Battalion at Sbeitla. Fortified in hull-down or partially concealed positions, 2nd Battalion awaited the enemy advance. Their right flank was covered by 2nd Battalion 6th Infantry, and the 1st AD Reconnaissance Company screened the flank and reported enemy movements. At least 40 tanks of the 21st Panzer Division were bearing down on them. Holding their concealed positions until the enemy drew near, the tanks of 2-13 Armor opened fire when their Commander, LTC Henry E. Gardiner commanded “Boys, let them have it!” 15 Panzers were destroyed or disabled, and the surprised enemy faltered, but the determined Germans managed to drive away 2nd Battalion's supporting M3 tank destroyers.[9]

While the rest of the battalions in CCB withdrew, 2-13 Armor stayed in Sbeitla to cover the withdrawal. When LTC Gardiner asked permission to withdraw, he was told to hold on a little longer, so the rest of the command could get through Kasserine Pass. At 1730 on 18 February 2nd Battalion was finally permitted to withdraw to safety. The withdrawal under fire was perilous, and the battalion lost nine M3 Lee tanks. LTC Gardiner made sure he was the last man to leave the field, but his tank was destroyed in the process and he was severely wounded, but managed to escape to friendly lines on foot during the night. For his outstanding leadership and courage in the defense of Sbeitla, LTC Gardiner received the Distinguished Service Cross. Rommel later praised the battalion's defense of Sbeitla, saying it was “clever and well fought.”[9]

The Germans were eventually stopped by the remnants of 2-13 and 3-13 Armor near Thala on 22 February. Although the enemy had pushed back the Allies, they were tired and spread thin. The Allied counter strike culminated at the Battles of El Guettar and Mateur, where tankers from 13th Armor showed the Germans that they had learned from their early mistakes, and were capable of fighting, and winning against the best. In early May 1943, one week before German forces in Africa ceased resistance, 2nd Battalion, 13th Armored Regiment was poised to take the seaside town of Bizerte. During the push to the city, 1LT Dwight Varner, from Piatt County, Illinois and a recent graduate of the University of Illinois, was leading his platoon in the attack, when his tank and eight others were knocked out by German anti-tank guns. 1LT Varner escaped his burning tank and managed to drag several crewmen to safety and provide first aid. However, he was wounded and captured. While marching to Tunis, he managed to escape his captors after three days and 40 miles of marching. Upon encountering seven Italian soldiers, he turned the tables and captured them by bluffing that the mess kit spoon in his pocket was a pistol. Commandeering the enemy’s vehicle, he then captured 18 unsuspecting Germans and drove them all back to American lines. 1LT Varner was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extreme gallantry and risk of his life while facing the enemy.[10][11][12]

All Germans in Africa surrendered by 15 May 1943, and the 13th Armor began training for its next assignment.[8]

Naples-Foggia

After victory in North Africa, the 1st Armored Division began training for its next operation. It was moved across the desert west to French-Morocco and was quartered in and around the city of Rabat where it underwent a major reorganization. General Ernest N. Harmon, commander of the 1st Armored Division, placed COL Hamilton H. Howze in command of the 13th Armored Regiment, and he quickly saw fit to rearm the Regiment with more modern equipment. The M3 Stuart light tanks were replaced by M5 Stuart light tanks, and the M3 Lee tanks were replaced by the M4 Sherman.[8] The Sherman tank would become the workhorse of the US Army, with over 50,000 of them being built during World War II. While 1st Armored Division was refitting in Morocco, other Allied forces invaded Sicily, and the men of Old Ironsides knew they would soon be headed into combat again. In September 1943, General Harmon reported to the Fifth Army commander, General Mark W. Clark, that the 1st Armored Division had completed rigorous training and was ready for combat operations once again. The 13th Armor landed in Italy near Naples in November 1943, where Allied units had already carved out a beachhead. After assembling in Capua, the Regiment waited in reserve. Their mission was to attack through the Liri Valley once infantry units had seized the surrounding heights.[8]

However, unlike Africa, the terrain of Italy is not suited for armored warfare. The Germans broke dams and flooded the countryside whenever they withdrew to mire the Allied advance. This also provided breeding ground for mosquitoes, leading to a malaria outbreak among Allied soldiers.[8] The winding rivers and steep mountains also proved difficult for the 13th Armor tanks to negotiate. Despite the cold, wet and miserable conditions, Christmas 1943 was greeted with considerable activity. Father Flaherty, the 13th Armored Regimental Chaplain, celebrated Mass in a Medieval village church. There was caroling, Christmas tree decoration, and music. The festivities ended on New Year’s Day, and the year of 1944 began with a German artillery barrage, further miring the Liri Valley and halting any hope of an American armored attack. The Allies began to look for other ways to break the stalemate in Southern Italy.[8]

Anzio

By January 1944, Allied forces had become stalemated along the German Gustav Line, which was anchored around the strong fortifications of Monte Cassino. The mud, mountains, and rivers made an armored breakthrough impossible. In order to defeat this defensive line, the Allies launched Operation Shingle, the amphibious invasion of Anzio, behind the Gustav Line. Combat Command A (CCA) of the 1st Armored Division was part of the initial landings, but CCB, including the 13th Armored Regiment, remained in the Cassino area ready to exploit any German weakness and attack through the Liri Valley should the opportunity arise. After intense German counterattacks on the Anzio beachhead and no meaningful progress south of the Gustav Line, it was decided to reunite the 1st Armored Division in order to make a decisive armored thrust to break out of Anzio. 13th Armor was shipped north to Anzio in early May 1944 after months of waiting. There, they received extensive training on breaching and the 191st Tank Battalion was attached to the Regiment for the coming attack. After rehearsing infantry-tank cooperation, the Regiment was in its pre-attack positions near Cisterna by 22 May.[8] On 23 May, 2nd Battalion 13th Armor jumped off at first light with D Co to the west, F Co to the east, and E Co in reserve. Attacking toward Torrecchia Nuova, the Battalion ran into an American minefield that was not properly marked. 40 total vehicles from CCB were damaged as a result.[8] D Co had so many tanks lose their tracks to mines that E Co advanced and assumed their mission. Despite this early setback, the tanks of Companies E and F rapidly advanced. They knocked out enemy anti-tank guns, bunkers, and trenches before setting into local security positions for the night.

Meanwhile, near Carano Creek on the American left flank, the German Army had launched a counterattack in the afternoon. 3-13 Armor, under LTC Cairns in Division reserve, drove away the Germans with the help of accurate artillery support. Tank recovery operations to repair damaged tracks and return the damaged tanks of 2-13 Armor to action went on for the duration of the night. Nearly all lost tanks were operational again within 48 hours.[8] The next day, 24 May, the attack continued. 2-13 Armor went forward, supporting 3-6 Infantry, and cleared out enemy positions in a forest and captured two artillery batteries. F Co, under CPT John C. Elliott, was sent to assist the 3rd Infantry Division to the west while the rest of 2-13 went into reserve. The light tanks of LTC Carr’s 1-13 Armor passed through 2-13’s lines and seized the Regimental objective, Torrecchia Nuova. The next day, 25 May, COL Howze was ordered to seize Giulianello, and the attack jumped off at dawn. Near the town of Valmontone, the 13th Armor engaged the infamous German Hermann Göring Division. 3-13 Armor blocked the road to west while 1-13 flanked the retreating Germans, capturing many. 2-13 Armor’s attack went well, but a German artillery shell killed its Executive Officer, MAJ George Johnson, and the attack stalled.[8] In order to capitalize on their gains, Task Force Howze (consisting of 3-13 Armor and supporting units) was formed to take Velletri and Giulianello. Working well with infantry support, the tanks of both CCB and TF Howze broke through the enemy lines while other armored units were halted by German anti-tank guns. The main highways to Rome, Routes 6 and 7, were opened for an Allied attack by 2 June 1944. During the Battle of Anzio, the 13th Armored Regiment saw its first real combat in the Italian Campaign. Although the fighting here was difficult and not ideal for armored warfare, the 13th Armor secured an Allied breakthrough and helped end the stalemate in Southern Italy.[8] Rome, the Italian capital, was finally within reach.

Rome-Arno

After achieving a breakout from the Anzio beachhead, 1st Armored Division tanks were positioned just south of Rome by 2 June 1944. Allied planners wanted to waste no time, and immediately ordered the tanks of the 13th Armored Regiment to advance to the “Eternal City.” LTC Cairns’ 3rd Battalion 13th Armor, part of Task Force Howze, led the way down Highway 6.[8] Despite sporadic enemy resistance, the retreating Germans could not stop the rapid advance. Meanwhile, on 3 June, the bulk of the 1st Armored Division advanced up Highway 7, with 1-13 and 2-13 Armor in Combat Command B (CCB). Allied units from across Italy were in a rush to be the first to enter Rome. The morning of 4 June 1944 began as a race. A Co, 1-13 Armor was sent ahead as a flying column while the rest of CCB broke into three columns advancing down parallel roads along Highway 7 to bypass Allied traffic and German defenses. TF Howze, to the east of the city, ran into strong German resistance just outside of city limits. By 0615, its 3rd Battalion, 13th Armor broke through and continued down Highway 6; eager infantrymen holding onto the backs of the fast-moving tanks. By 0715, H Co, 3-13 Armor, under CPT John A. Beale, became the first American element to enter the Eternal city; The lead tank was commanded by SGT Abner.[8] However, after turning a corner, his tank and another were both hit by anti-tank gun fire; the Germans weren’t going to give up so easily.[8] For hours, TF Howze battled with German roadblocks in the city, slowly clearing the streets. Companies G, H, and I rolled to the northwest to cut off a German armored counterattack. After his tank was disabled, LTC Cairns, commanding 3-13 Armor, took command of CPT Beale’s tank, resulting in the odd scenario where a Company Commander acted as the gunner for his Battalion Commander. Together, the two commanders found and knocked out several enemy vehicles.[8]

Meanwhile, the rest of the 13th Armored Regiment advanced quickly up from the south, capturing numerous prisoners and surprising many Germans who didn’t expect the Allies to be so far north. By the end of 4 June 1944, Rome was completely in Allied hands. Italian citizens thronged the streets, kissing the GIs and giving them flowers.[8] The 1st Armored Division quickly moved north of the city and prepared for the next attack; along the coastal plain to the Arno River. Although the capture of Rome was a major win for the Allies, public and military attention quickly shifted elsewhere. On 6 June 1944, the Invasion of Normandy began, opening another front against the Axis. Allied forces in Italy would now be a secondary effort.

From 6-10 June, 1-13 and 2-13 advanced 25 miles north of Rome meeting only scant resistance. The relatively flat land of the Italian coastal plain was much more suited to armored warfare than the terrain of Southern Italy. By 22 June, 1AD again ran into steep mountainous terrain, and all attacks north were stalled.[8] Grinding north again, the 13th Armor engaged and defeated German elements in numerous battles and skirmishes as the retreating enemy tried to delay the Allied advance. CCB and TF Howze became adept at defeating German armored elements, and the Arno River was finally reached on 18 July 1944, but the 1st Armored Division needed a rest. After pulling back, the Division was completely reorganized on 20 July. The 13th Armored Regiment was reduced in size and was redesignated as the 13th Tank Battalion. 1-13 Armor was disbanded, and its tanks and crews went on to replace others lost in combat. Companies D, E, and F of 2-13 Armor became Companies A, B, and C of the 13th Tank Battalion (M4 Shermans). B Co of 1st Armored Regiment became D Co, 13th Tank Battalion (M5 Stuarts). Companies G, H, and I of 3-13 Armor left and formed the 4th Tank Battalion. The 13th Tank Battalion now had an effective strength of 804 tanks, and it soon began preparing to meet the next formidable German defensive position; the Gothic Line.[8]

North Apennines

Despite a rapid Allied advance into and beyond Rome, the Italian Front had stalemated once again at the German Gothic Line. The 13th Tank Battalion, commanded by LTC Henry E. Gardiner, was assigned to Combat Command B (CCB), commanded by COL Lawrence Russell Dewey, for the coming offensive. On 1 September 1944, CCB crossed the Arno river with combined tank and infantry columns and met only scant resistance. Swiftly advancing, CCB captured the town of Altopascio on 4 September, and the 13th Tank Battalion continued its steady advance.[8] On 10 September, the tankers faced their first real German resistance of the offensive, but they continued to apply pressure to the enemy’s western flank to divert German troops from Fifth Army’s main effort at Il Giogo Pass. On 25 September 1st Armored Division was split up. The steep mountains and foothills of the Apennine Range were ill-suited to rapid armored assaults, and the Combat Commands of the Division were attached to infantry units to provide them with necessary tank support. 13th Tank Battalion was assigned to “Task Force 92” under BG John E. Wood. TF 92 was a component of the 92nd Infantry Division, a “Colored Division” in the segregated Army of WWII. TF 92 and 13th Tank Battalion worked together well, and from 26-29 September, they launched a large attack on German positions on the Gothic Line.[8] They managed to capture the town of Lucchio and push the enemy out of the Serchio Valley. By the end of September 13th Tank Battalion and TF 92 was attacking down Highway 64 toward Vergato, operating independently of the 1st Armored or the 92nd Infantry Divisions.[8]

On 6 October 13th Tank was temporarily attached to the “6 South African Armoured Division.” The 1st Armored Division now held the extreme western flank of the II Corps Zone.[8] Throughout October, the 13th Tank Battalion, on the left flank of CCB, pushed up the mountain slopes along Highway 64. First they reached Porretta Terme, and then near the end of the month, arrived beyond the town of Riola. An attack on 29 October against German positions at Castelnuovo was stopped short. The Germans counterattacked, but 13th Tank defeated them. In a last-ditch effort, the enemy destroyed all nearby bridges, forcing CCB to halt its attack. On 10 December 1944, after a month of inactivity on the front-line, 13th Tank Battalion was attached to the Allied Brazilian Expeditionary Force in an attack against Monte Castello, but they were repulsed by the Germans.[8] As the winter cold and rain set in, both sides in this sector maintained defensive positions along the stalemated front. Late in 1944 and in early 1945, D Company’s M5 Stuart light tanks began to be replaced by the more modern M24 Chaffee light tanks. The Chaffee was a vast improvement over the Stuart, as its 75mm gun more than doubled the firepower of the Stuart’s 37mm gun. Throughout the winter, Companies A, B, C, and D conducted training and refitting for the coming campaign.[8]

Po Valley

By early 1945, German forces in Western Europe had been defeated at the Battle of the Bulge, and Allied units were steadily advancing into Germany. In Italy, the German and Fascist Italian remnants were depleted, but still occupied strong defensive positions anchored by steep mountains ranges. Beyond this line, lay the Po Valley to the north. The Po Valley is flat, wide, and perfect for offensive armored warfare; if Allied forces could break through to it, the war in Italy could be swiftly won.[8] Furthermore, Allied units needed to reach the valley in order to cut off retreating German forces before they could reach the Alps in Austria and Bavaria and set up stronger defenses. 1st Armored Division began its attack on 14 April 1945. A Co, and 2nd Platoon of C Co, were in Combat Command B (CCB), the Division’s main effort, while the remainder of 13th Tank Battalion was placed in reserve. A Co and 2nd Platoon of C Co had 34 tanks, including 17 Shermans equipped with high velocity 76mm guns, and 9 M4A3 Shermans equipped with 105mm guns. The tanks were to support the 6th, 11th, and 14th Armored Infantry Battalions in their advance. At 1630, the attack jumped off under the cover of a smoke screen laid down by Division Artillery. The tanks and infantry met determined German resistance but captured their objectives by 17 April.[8]

Meanwhile, an M4 Sherman platoon from 13th Armor was detached to assist the 81st Cavalry Squadron in seizing Piano di Venola. After meeting stiff resistance along Highway 64, the Troopers and Tankers of the force were near their objective by 17 April as well.[8] During the advance, the rest of 13th Tank Battalion remained in Division reserve, ready to exploit a breakthrough. On 20 April, 13th Tank Battalion was attached to Combat Command A (CCA). With A Co on the right, B Co on the left, and C Co in reserve, 13th Tank Battalion attacked alongside the 6th Armored Infantry Battalion into the Po Valley. After a rapid advance, 13th Tank encountered fierce resistance at the town of Oliveto, losing 3 tanks from C Co, but ultimately securing victory, and taking 179 German prisoners. 1st Armored Division elements had at last reached the Po Valley, and were ready to strike. 13th Tank Battalion’s Commander, LTC Henry E. Gardiner, took A Co and D Co to cut Highway 9, while the Executive Officer, MAJ John C. Elliot, took B Co and C Co northwest to occupy Castelfranco. By the end of 21 April, these objectives were secured, and many Germans were taken prisoner. The 13th Tank Battalion continued its audacious drive north and west, cutting through German lines and defeating or capturing any enemies it encountered. By the end of 23 April, the Battalion had crossed the Po River, and it captured the city of Verona by 26 April.[8] Speeding to the northwest, the 1st AD began capturing thousands of German prisoners; they knew the war was lost and were not keen on fighting powerful Allied armored units anymore. On 28 April, it was revealed that Mussolini had been captured and executed by Italian partisans, and soon after, C Co of the 13th Tank Battalion entered the city of Milan.[8] The next day, the German commander, General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, surrendered and the fighting in Italy ceased on 2 May 1945. Hitler committed suicide soon after, and WWII in Europe ended on 8 May 1945. The 13th Tank Battalion soon moved into occupied West Germany to begin its post-war duties. WWII was the 13th’s longest and deadliest conflict. Despite a steep learning curve at Kasserine Pass, the unit proved itself in Tunisia and Italy, earning itself a decorated place in American military history.

Cold War

As part of the post-war Allied Occupation of Germany, The 13th Tank Battalion was converted, reorganized, and redesignated on 1 May 1946 as the 13th Constabulary Squadron, an element of the 10th Constabulary Regiment.[13] It was inactivated on 20 September 1947 in Coburg, West Germany and relieved from assignment to the 10th Constabulary Regiment. On 7 March 1951, it was reactivated as the 13th Medium Tank Battalion and was assigned, once again, to the 1st Armored Division at Fort Hood, Texas. On 20 May 1953, its designation was changed back to the 13th Tank Battalion. The Battalion was inactivated on 15 February 1957 at Fort Polk, Louisiana and was reactivated later that year, 1 October 1957, and was assigned to the 3rd Armored Division in Germany.[13]

On 3 February 1962 2nd Battalion, 13th Armor was relieved from assignment to the 3rd Armored Division and was assigned to the 1st Armored Division.[13] On 5 May 1971 it was relieved from assignment to the 1st Armored Division and was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division at Fort Hood and was inactivated on 23 April 1973. On 20 June 1974, 1st Battalion, 13th Armor rejoined the 1st Armored Division at Illesheim, Germany until 20 February 1987, when the Battalion moved to Vilseck, Germany. 13th Tank remained here until 1988, when it was inactivated and re-designated as 2nd Battalion, 13th Armor at Fort Knox, Kentucky.[13]

Bosnia

At Fort Riley, Kansas in March 1996, 3rd Battalion, 37th Armor Regiment cased its colors and reflagged as the 1st Battalion, 13th Armored Regiment, with the Soldiers exchanging their 1st Infantry Division patches for the "Old Ironsides" patches of the 1st Armored Division. LTC Richard G. Jung Sr. commanded the "Dakota" Battalion from 1996–98, honoring the Regiment's history with the Battalion name and call sign. Called "13th Tank" by those who served in the unit, 1-13 Armor was one of two armor battalions in 3rd Brigade, 1st AD (Bulldogs) under the command of COL Joseph F.H. Peterson.

In January 1997, A Company (Ironhorse), 1-13 Armor, under CPT Paul P. Reese, was alerted for deployment to Europe as part of the ongoing peacekeeping effort in the former Yugoslavia. In March, A Company was attached to 1st Battalion, 41st Infantry Regiment, 1-41 Infantry, and deployed to Bosnia-Herzegovina in support of Operation Joint Guard. The Company was stationed at Camp Dobol near the zone of separation (ZOS) as the first iteration of "SFOR" or the "Stabilization Force" after the designation changed from "IFOR" or the "Implementation Force" in early 1997, "Team Tank" conducted a variety of missions and patrols in accordance with the General Framework Agreement for Peace (GFAP) and corresponding rules of engagement (ROE) while operating within its area of responsibility. The company operated near the Bosnian-Serbian (Republika Srpska) towns of Šekovići, Bratunac and the infamous Srebrenica. A/1-13 AR consisted of 2 M1A1 tank platoons and 1 M2A2 Bradley platoon (1 organic tank platoon was detached and assigned to A/1-41 IN at Camp Demi). Ironhorse company returned to the 1st Battalion, 13th Armored Regiment in December, 1997 upon redeployment to Fort Riley at the successful completion of their mission.

Iraq War

In March 2003, the United States invaded Ba'athist Iraq to depose the dictator Saddam Hussein and remove Iraq as a safe haven for international Islamic terrorism. 1st Battalion, 13th Armor Regiment, known as Task Force Dakota, arrived on 1 April 2003 to augment units of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division who had spearheaded US assaults to the south of Baghdad.[14] The Brigade was attached to the 3rd Infantry Division and controlled the Kadhimiya area of Baghdad immediately after the initial invasion of Iraq. TF Dakota participated in numerous operations aimed at subduing insurgents including Operation Bulldog Flytrap, Operation Bulldog Mammoth, and Operation Cancer Cure. The Battalion redeployed to Fort Riley, Kansas on 2 April 2004.[15] Less than a year later, in February 2005, the 3rd BCT deployed to Iraq for a second time, again attached to the 3rd Infantry Division. TF Dakota was primarily stationed north of Baghdad in the Taji, Mushahda, Tarmiyah, Husseiniya, and Rashidiya districts. The Battalion was redeployed to Ft. Riley in January 2006.[16][17]

The 2nd Squadron, 13th Cavalry Regiment stood up in 2008 as part of 4th Brigade Combat Team (Highlanders), 1st Armored Division at Ft Bliss, Texas. The Squadron deployed to Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom from May 2009 to May 2010. The 1st Squadron, 13th Cavalry Regiment (Warhorse) stood up in 2009 as part of the 3rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division at Fort Bliss, TX. In April 2009, 4th Brigade, including 2-13 Cavalry, deployed to the southern Iraqi provinces of Dhi Qar, Maysan, and Al-Muthanna, as the Army's first "advise and assist brigade," a concept in which US forces would take a backseat to Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) and local government officials. The Brigade, under the command of COL Peter A. Newell and CSM Phillip D. Pandy, partnered with provincial reconstruction teams, civil affairs teams, US Department of State officials, and military transition teams, while assisting ISF and the Government of Iraq. The Brigade's partnership allowed over one million voters to participate in the election of 2010. For their actions in assisting elections in Iraq, 2nd Squadron, 13th Cavalry Regiment earned the Meritorious Unit Commendation.

In July 2011, the 4/1 AD Highlanders deployed to Iraq in support of Operation New Dawn. The Brigade deployed under the command of COL Scott McKean, who later served as the 1AD Deputy Commanding General for Operations. 2-13 Cavalry served with the Brigade for the entirety of this deployment and was a key part in maintaining security while US forces withdrew from Iraq. 4th Brigade was one of the last units to withdraw from Iraq as part of the closing of Operation New Dawn.

Afghanistan War

1st Squadron, 13th Cavalry Regiment (TF 1-13 Cavalry), as part of the 3rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Division, (TF 3-1AD), deployed from Fort Bliss, Texas to eastern Afghanistan (RC-East) on 16 October 2011. The Brigade conducted combined, population-centric counterinsurgency operations in Logar, Wardak, and Bamyan provinces, relieving the 4th Brigade, 10th Mountain Division. TF 3-1 AD and partners worked to secure Highway 1, a vital line of communication, neutralize insurgent and criminal networks, and train the Afghan National Security Forces in order to expand the Kabul Security Zone and extend the Afghan Government's influence among the local people. In mid-October, TF 3-1 AD launched the brigade's first operation, Operation Shamshir. Planned in support of an RC-East operation to disrupt insurgents from the Haqqani Network across eastern Afghanistan, the operation disrupted and dislodged insurgents from their entrenched positions and forced them into the open. A total of 14 villages in the Kharwar District were cleared and the operation concluded with a Shura among key leaders. As the Afghan winter set in, TF 3-1 AD continued to target insurgent supply caches, disrupt support zones, and expand the Afghan government's authority. The Brigade and their Afghan partners continued to push the enemy south, expanding the Kabul security zone.

On 15 April 2012, insurgents launched the opening salvos of their spring offensive. Coordinated attacks targeting coalition and Afghan military bases and embassies were carried out in Kabul, Paktiya, Kunar, and Logar Provinces. The enemy attacks were defeated by a combination of TF 3-1 AD Soldiers, Afghan partners, and close air support. In all, 11 insurgents were killed in action. In May 2012, TF 1-13 Cavalry assumed control for all of northern Logar Province and planned and resourced the movement of two additional Afghan National Army battalions (Kandaks) into the area. On 15 July 2012, TF 1-13 Cavalry and the rest of TF 3-1 AD returned to Fort Bliss, Texas.

Global Security Rotations

Following the 4th Brigade's re-flagging as 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division in 2015, 1-13 Cavalry inactivated on 15 April 2015 as part of the Brigade's inactivation, and the 2nd Squadron 13th Cavalry Regiment, now part of 3rd ABCT, participated in the Brigade's Regionally Aligned Force mission throughout the continent of Africa. The Squadron sent Troopers on various train and assist missions to multiple countries on the African continent to include: Malawi, Morocco, Ethiopia, Namibia, and Zambia. As a result of these missions, the Squadron directly supported the United Nations' Peace Keeping operations, enhanced the Army's geo-political impact, and increased the readiness of America's African allies and partners throughout the continent.

In July 2016, 2-13 Cavalry Squadron assumed responsibility of the US Army Central Command theater security cooperation and partnership missions at Camp Buehring, Kuwait, in support of Operation Spartan Shield. By strengthening partnerships with the United Arab Emirates Armed Forces, the Royal Army of Oman, and the Kingdom of Bahrain, the efforts of the entire Squadron contributed to peace and stability in the region.[18]

From fall 2018 to the summer of 2019, 2-13 Cavalry served in the Republic of Korea, working closely and training with the ROK Army. Their rotation on the Korean Peninsula helped deter North Korean aggression and maintained peace in the region.

Current status

2nd Squadron is the armored reconnaissance squadron of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division stationed at Fort Bliss, Texas. With the inactivation of 1-13 CAV in April 2015, 2nd Squadron became the Regimental Home-Base Squadron.[19] It currently remains the only active Squadron in the 13th Cavalry Regiment.

The Squadron's composition is as follows:

- Hatchet Troop - Headquarters

- Apache Troop - M2A3 Bradley Reconnaissance

- Blackfoot Troop - M2A3 Bradley Reconnaissance

- Crazy Horse Troop - M2A3 Bradley Reconnaissance

- Damage Troop - M1A2 Abrams Tank

- Dagger Company - Forward Support Company

See also

References

- "Special Unit Designations". United States Army Center of Military History. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/1-13ar.htm

- Army, The Campaign for the National Museum of the United States (28 January 2015). "13th Armor". The Campaign for the National Museum of the United States Army. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Prieto, Julie (2016). The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War I: The Mexican Expedition 1916-1917. Alexandria, VA: St. John's Press.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 July 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Cameron, Robert (2017). ARMOR IN BATTLE: Special Edition for the Armored Force 75th Anniversary. Fort Benning, GA: U.S. Army Armor School.

- Atkinson, Rick. An Army at Dawn.

- Howe, George (1954). The Battle History of the First Armored Division. Washington, D.C.: Combat Forces Press.

- "13th Cavalry Regiment". Association of 3d Armored Division Veterans. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018.

- Republican, Journal. "Dwight Steve Varner". Journal Republican. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- News-Gazette, The. "Steve Varner". The News-Gazette. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Robinett, Paul McDonald (2017). Armor Command: The Personal Story of a Commander of the 13th Armored Regiment, of CCB, 1st Armored Division, and of the Armored School during World War II. Arcole Publishing. p. 289.

- "2d Squadron, 13th Cavalry Regiment | Lineage and Honors | U.S. Army Center of Military History (CMH)". history.army.mil. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- "3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- 13th Armor Regiment

- "Operation Lightning: Soldiers strike at Terrorists in Taji - DefendAmerica News Article". Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Armor and Cavalry Regimental Guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2019.