Battle of El Guettar

The Battle of El Guettar was a battle that took place during the Tunisia Campaign of World War II, fought between elements of the Army Group Africa under General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim, along with Italian First Army under General Giovanni Messe, and U.S. II Corps under Lieutenant General George Patton in south-central Tunisia. It was the first battle in which U.S. forces were able to defeat the experienced German tank units, but the followup to the battle was inconclusive.[2]

| Battle of El Guettar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tunisia Campaign of World War II | |||||||

An American soldier hands out cigarettes to captured Bersaglieri of the 131st Armored Division "Centauro" near El Guettar in March 1943. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

22 tanks lost 4 halftracks lost[3] 4,000–5,000 killed or wounded |

37 tanks lost[3] 4,000–6,000 killed or wounded in 3 weeks | ||||||

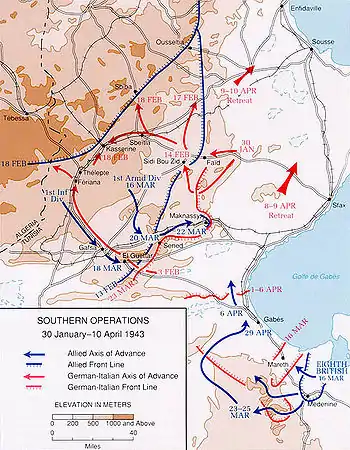

Background

The U.S. II Corps had been badly mauled in its first encounter with Axis forces in Tunisia during a series of battles that culminated in the disastrous Battle of the Kasserine Pass in late February 1943. Erwin Rommel—poised on the threshold of a complete tactical victory—turned from the battle to return to his eastward-facing defenses at the Mareth Line when he heard of the approach of Bernard Montgomery′s British 8th Army. Thus the battle concluded with the U.S. forces still in the field, but having lost ground and men, and with little confidence in some key commanders.

In the last week of January 1943, despite a massive artillery bombardment, the Italian 14th Bersaglieri Battalion of the 131st Armoured Division Centauro dug in near Djebel Rihana.[4] Harold V. Boyle, an Irish war correspondent, wrote that a second attack was required using grenades and bayonets in order to evict the Italians:

Artillery and aircraft may harass but cannot dislodge him. Only bullets and bayonets of rival riflemen can do that. This was well illustrated in the Ousseltia Valley campaign in January when tanks and artillery laid down one of the finest barrages of the campaign but couldn't rout Italians dug in like moles in the hills bordering the road to Kairouan. The artillery was beautiful to see but they couldn't do the job alone. Finally American infantry swarmed up the hills at night and flushed the Italians out in droves with hand grenades and the pointed persuasion of their bayonets.[5]

The American command reacted to its reverses against German and Italian forces with a prompt and sweeping series of changes in command, discipline, and tactics. Also, large units were kept massed rather than being broken up into smaller, unsupported elements as had been done under U.S. II Corps Commander Lloyd Fredendall. Close air support was also improved.

On 6 March 1943, George Patton took command of the U.S. II Corps from Lloyd Fredendall, who had been in command before and during the Kasserine engagement. His first move was to organize his U.S. II Corps for an offensive back toward the Eastern Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains. If successful, this would threaten the right rear of the Axis forces defending the Mareth Line facing Montgomery's 8th Army and ultimately make their position untenable. Patton's style of leadership was very different from his predecessor: he is reported to have issued an order in connection with an attack on a hill position ending "I expect to see such casualties among officers, particularly staff officers, as will convince me that a serious effort has been made to capture this objective".[6]

On 17 March, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division moved forward into the almost abandoned plains, taking the town of Gafsa and preparing it as a forward supply base for further operations. On the 18th, the 1st Ranger Battalion—led by Colonel William O. Darby—pushed ahead, and occupied the oasis of El Guettar, again meeting with little opposition. The Italian defenders instead retreated and took up positions in the hills overlooking the town, thereby blocking the mountain pass (of the same name) leading south out of the interior plains to the coastal plain. Another operation by the Rangers raided an Italian position and took 200[7] prisoners on the night of 20 March, scaling a sheer cliff and passing ammunition and equipment up hand-over-hand.

Battle

The Axis army commanders had become aware of the U.S. movements and decided that the 10th Panzer Division should stop them. Rommel had departed Tunisia for Germany on 9 March before the battle, leaving von Arnim in control of the newly named Africa Korps. Von Arnim also held Rommel's opinion on the low quality of the American forces and felt that a spoiling attack would be enough to clear them from the Eastern Dorsals again.

At 06:00 on 23 March, 50 tanks of Broich's 10th Panzer emerged from the pass into the El Guettar valley at 34°20′12″N 8°56′53″E. German motorised units in halftracks and motorcycle sidecars broke off from formation and charged the infantry on the top of the hill. The halftracks would move up the hill as far they could and then the infantry they carried would dismount while covered by fire from 88mms. The Germans were maneuvering to hit American artillery anchored on the hill. They quickly overran front-line infantry and artillery positions. Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr.—commanding the U.S. 1st Infantry Division—was threatened when two tanks came near his headquarters, but he shrugged off suggestions of moving, "I will like hell pull out, and I'll shoot the first bastard who does."[8]

The German attack lost momentum when it ran into a minefield. When the Germans slowed to reorganise, U.S. artillery and anti-tank guns engaged, including 31 M10 tank destroyers which had recently arrived. Over the next hour, 30 of the 10th Panzer's tanks were destroyed, and by 09:00 they retreated from the valley.

A second attempt was made at 16:45, after waiting for the infantry to form up. Once again the U.S. artillery was able to disrupt the attack, eventually breaking the charge and inflicting heavy losses. Realizing that further attacks were hopeless, the rest of the 10th Panzer Division dug in on hills to the east or retreated back to the German headquarters at Gabès.

Allied attacks

On 19 March, the British 8th Army launched their attack on the Mareth Line, at first with little success.

Over the next week, the U.S. forces slowly moved forward to take the rest of the interior plains and set up lines across the entire Eastern Dorsals. The German and Italian defenses and reserves were heavy, and the progress was both slow and costly. On 23 March, the 10th Panzer Division attacked Lieutenant-Colonel Robert H. York's 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, and the German tanks broke through the valley between the 3rd and 1st Battalions of the 1st Division, reaching a position about six miles to the rear of the 1st Battalion.[9] In the action, the German tanks and self-propelled guns along with German troops riding in carriers and trucks overran the 32nd Field Artillery Battalion and part of the 5th Field Artillery Battalion,[10] and the Italian High command reported that 40 tanks had been destroyed and 170 Allied troops had been captured in "central and southern Tunisia".[11]

On 26 March, in Operation Supercharge II, a British force sent via an outflanking inland route attacked the Tebaga Gap to the north of the Mareth line, and their breakthrough left the Mareth defenses untenable. The Axis forces retreated about 40 miles to a new line set up at Wadi Akarit, north of Gabès at 33°53′3″N 10°5′33″E. This made the U.S. position even more valuable, since the road through El Guettar led directly into Gabès.

By 30 March the U.S. forces were in position for an offensive south from El Guettar. In order to start a breakout, the two original Italian strongpoints on Hill 369 34°14′29″N 9°7′16″E and Hill 772 34°12′7″N 8°59′36″E had to be taken, one after the other.[12]

The U.S. plan involved the U.S. 1st and 9th Infantry Divisions, and Combat Command 1/3 of the U.S. 1st Armored Division, collectively known as "Benson Force". This force attacked Hill 369 on the afternoon of 30 March but ran into mines and anti-tank fire, losing five tanks and a rifle company from the 2nd Battalion of Colonel Edwin H. Randle's 47th Infantry Regiment that was forced to surrender.[13] The tanks were withdrawn, and the 1st and 9th attacked again the next day at 06:00, gaining some ground and taking several hundred prisoners. However, an Italian counter-attack drove them back from their newly gained positions, and by 12:45 they were back where they started with the loss of nine tanks and two tank destroyers. A further attempt the next day on 1 April also failed, after barely getting started. Private Emil J. Dedonato remembers that Patton drove up to the 47th Regiment's command post, unhappy that the initial attacks had failed:

Patton was in a huffy mood and stormed over to see Colonel Randle in his Jeep. It was obvious he wasn't pleased with the initial results of the night attack. I'll never forget Colonel Randle's instructions as they moved into El Guettar: "Where we're going you won't need a physic!"[14]

At this point Patton received orders to start the attempt on Hill 772, even though Hill 369 was still under Italian control. The 9th was moved to Hill 772, leaving the 1st on Hill 369. By 3 April, the 1st had finally cleared Hill 369, but the battle on Hill 772 continued. The Italian commander—General Messe—then called in support from the German 21st Panzer Division, further slowing progress. The tempo of the operations slowed, and the lines remained largely static.

Aftermath

On 6 April, the British 8th Army once again overran the Axis lines at the Battle of Wadi Akarit, and a full retreat started. On the morning of 7 April, Benson Force moved through the positions held by the 1st and 9th divisions, and raced down the abandoned El Guettar-Gabès road, where it met the lead elements of the 8th Army at 17:00. With the last Axis line of defense in the south of Tunisia broken, the remaining forces made a run to join the other Axis forces in the north. Tunis fell to the Allies in early May.

Dramatic portrayals

- The first part of the battle is portrayed in a lengthy scene in the 1970 biographical film Patton.

Footnotes

- Hooker Jr. p. 85

- Haycock p. 42

- "American Tank Destroyers at El Guettar". Warfare History Net.

- Terrible Terry Allen: Combat General of World War II - The Life of an American Soldier, Gerald Astor, p. 139, Random House, 2008

- Tunisia Campaign Puts U.S. Infantryman Back On Pedestal

- Hunt (1990), p. 169.

- "In March 1943 the 1st Ranger Battalion led Gen. Patton's drive to capture the heights of El Guettar with a 12-mile night march across mountainous terrain, with intent to surprise the enemy positions from the rear. By dawn the Rangers swooped down on the surprised Italians, cleared the El Guettar Pass, captured 200 prisoners, and then held their positions against a series of enemy counterattacks." Darby's Rangers 1942-45, Mir Bahmanyar, p. 9, Osprey Publishing, 2012

- Atkinson, p. 440

- Infantry Journal, Volumes 54-55, p. 42, United States Infantry Association, 1944

- George F. Howe (1957), "Chapter XXVIII: Gafsa, Maknassy, and El Guettar (17-25 March)", Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Northwest Africa: Seizing the Initiative In the West, United States Army in World War II

- "Yankee Units Within Hour's Drive of Sea; Blast 30 Nazi Tanks" Reading Eagle March 24, 1943 p18

- "Fought in the rugged region south of Gafsa, the Battle of El Guettar was a bona fide victory that did show American mettle ... Infantrymen of the 9th Infantry Division were in the thick of the action in the mountainous region. Italians accounted for most of the enemy forces." I Was with Patton, D. A. Lande, p.50, Turner Zenith Imprint, 2002

- The 9th Infantry Division: Old Reliables, John Sperry, p.11, Turner Publishing Company, 2000

- 9th Division Veterans www.ww2survivorstories.com

Bibliography

- Atkinson, Rick (2002). An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942–1943. New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 0-8050-6288-2.

- Hunt, David (1990) [1966]. A Don at War (rev. ed.). Great Britain: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-3383-6.

- Anderson, Charles R. (1993). Tunisia 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-038106-1. CMH Pub 72-12.

- Haycock, D.J. (2004). Eisenhower and the Art of Warfare: A Critical Appraisal. McFarland. ISBN 9780786418947.

- Hooker Jr, Richard D (2014). Wrath Of Achilles: Essays On Command In Battle. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 9781782893905.

- Howe, G. F. (1957). Northwest Africa: Seizing the Initiative in the West. Washington: Department of the Army. Reprinted in 1991. ISBN 0160019117 OCLC 23304011

- Howe, George F. (1954). The Battle History of the 1st Armored Division, "Old Ironsides.". Washington: Combat Forces Press. OCLC 1262858.

- Kelly, Orr (2002). Meeting the Fox: The Allied Invasion of Africa, from Operation Torch to Kasserine Pass to Victory in Tunisia. New York: Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-41429-2.

- King, Michael J. (1985). Rangers: Selected Combat Operations in World War II. US Army Combat Studies Institute, Command and General Staff College. LCCN 85015691. OCLC 12263177.

- Levine, Alan (1999). The War Against Rommel's Supply Lines. Westport, CT.: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-96521-1.

- Middleton, Drew (20 March 1943). "US Force at Pass". The New York Times.

- Moorhead, Alan (1968). The March to Tunis: The North African War, 1940-1943. New York: Dell Publishing. OCLC 12298236.

- Wickware, F. G. (1944). The American Yearbook. New York: Nelson.