1955 British Kangchenjunga expedition

The 1955 British Kangchenjunga expedition succeeded in climbing the 28,168-foot (8,586 m) Kangchenjunga, the third highest mountain in the world, for the first time. The expedition complied with a request from the Sikkim authorities that the summit should not be trodden on so the climbers deliberately stopped about five feet below the summit. George Band and Joe Brown reached the top on 25 May 1955, and they were followed the next day by Norman Hardie and Tony Streather. The expedition was led by Charles Evans who had been deputy leader on the 1953 British Mount Everest expedition.

Back: Tony Streather, Norman Hardie, George Band and John Clegg

Front: Neil Mather, John Jackson, Charles Evans and Joe Brown

The expedition trekked from Darjeeling in India along the border with Sikkim and then through Nepal to the Yalung Valley. They unsuccessfully attempted a climbing route reconnoitred by a team led by John Kempe the year before but succeeded along a different route up the Yalung Face, one that Aleister Crowley's 1905 Kanchenjunga expedition had first attempted.

In mountaineering circles at the time and more recently, the climb is sometimes regarded as a greater achievement than the ascent of Mount Everest two years earlier.

Background

Political

Following the ascent of Everest in 1953 and K2 in 1954, Kangchenjunga, the third highest mountain in the world, had become the highest unclimbed mountain.[1] The mountain is on the border between Nepal and Sikkim and can be approached from either side.[2] It is the most widely visible of the 8000-metre peaks and can be well seen from Darjeeling in West Bengal. In 1955 Sikkim had a degree of control over its internal affairs and would not allow any attempt to climb the mountain.[3] However, from 1950 Nepal had been permitting a few mountaineering expeditions, particularly enabling reconnaissance of routes to Everest, and were willing to allow an attempt on Kangchenjunga from the west.[4]

Exploration

Kangchenjunga is a highly active mountain with avalanches constantly streaming down its sides. It is somewhat distanced from the line of the Himalayas and, because it is near where the monsoon approaches from the Bay of Bengal the monsoon season persists longer than for any other of the eight-thousanders.[5] Throughout the 20th century and from even before that time, the mountain had been explored by many teams and the two routes attempted in 1955 – up the Yalung Face of the mountain from the Yalung glacier – had been reconnoitred in 1905 by a Swiss team led by Jules Jacot-Guillarmod with Aleister Crowley as climbing leader[note 1] and by John Kempe in 1954.[note 2] Kempe's report led to the Alpine Club agreeing to sponsor a reconnaissance effort which might also attempt to reach the summit.[7][8]

A detailed map of the region was produced by Marcel Kurz in 1931.[9]

Expedition planning and departure

Team membership

The members of the team were Charles Evans (36 years at the time of the climb), who had been deputy leader on the 1953 British Mount Everest expedition. Norman Hardie (30 years), a New Zealander, who was deputy leader and had explored the Barun Valley with Edmund Hillary in 1954. George Band (26 years), had been on the 1953 Mount Everest expedition and was responsible for food. Joe Brown (24 years), an outstanding rock climber in Britain and the Alps. John Clegg (29 years), the expedition doctor and an Alpine climber. John Jackson (34 years), with considerable Himalayan experience. He had been on the 1954 Kangchenjunga reconnaissance expedition. Tom McKinnon (42 years), the expedition photographer with considerable Himalayan experience. Neil Mather (28 years), an ice and snow climber in the Alps. Tony Streather (29 years), with broad mountaineering experience including on the 1953 American Karakoram expedition. He was responsible for porters and had knowledge of Hindustani. Dawa Tensing (about 45 years), was sirdar (chief Sherpa). He had been Evans' personal Sherpa on the 1952 Cho Oyu and 1953 Everest expeditions where he had twice reached the South Col.[note 3] Annullu, deputy sirdar, had also been at the South Col in 1953. There were about 30 Sherpas from Solu Khumbu[note 4] and 300 porters from Darjeeling.[11]

Equipment

Considerable advances had been made in equipment for the 1953 Everest expedition and so changes for 1955 were less substantial. Rather than taking vacuum packed high-altitude food they took packs for ten-man-days to be shared out so individual tastes could be better accommodated. Their high-altitude boots were of a neater design which allowed for canvas overboots and crampons on top of the whole lot. Their oxygen equipment was improved in design. The climbers used supplemental oxygen above Camp 3 and the Sherpas above Camp 5. They took two closed-circuit sets, largely for experimental purposes but they relied on open-circuit which were also found to be generally more satisfactory. A set weighed only 80% of the Everest design.[12] The flow valves were made of rubber to avoid problems of blockage by ice but unfortunately, when the rubber became cold and rigid overnight, the valves would leak badly when turned on in the morning. Early starts were sometimes delayed while the equipment was being warmed up.[13] Another problem was that the climbers lost weight during the climb so that their face masks no longer fitted well and this also caused a waste of gas. Worse, the leak could cause their goggles to mist up – removing these, even just to wipe them, risked becoming snowblind.[14][15] In all, 6 long tons (6.1 tonnes) of supplies had to be carried from Darjeeling.[16]

Departure for Darjeeling

Shortly before they sailed from Liverpool on 12 February 1955 they were told that for spiritual reasons the Sikkim government objected to any attempt at all to climb the mountain, even from Nepal, so before they departed Darjeeling Evans went to Gangtok to visit the Dewan (prime minister) with whom he reached a compromise that the expedition could go ahead provided that once they were sure of being able to reach the summit they would go no higher and they would not desecrate the vicinity of the summit.[3][17][note 5]

March-in and first base camp

They left Darjeeling on 14 March for the 16-mile (26 km) journey to Mane Bhanjyang transporting their baggage in a convoy of dilapidated trucks.[note 6] This was the last large village on the road before their 10-day trek started on a track up to the crest of the Singalila Ridge from where, at 10,000 feet (3,000 m), there were three Indian government rest houses along the route north, the first being at Tonglu. At Phalut they turned west to enter the jungles of Nepal.[20] After Chyangthapu they headed north again through intensively cultivated terraced land. At Khebang (now Khewang) there was a long climb up to the pass leading to the Yalung valley where there was again jungle, which eventually turned into the gravel outwash of the Yalung glacier. After Tseram (now Cheram) was the remains of a monastery at Ramser and near the terminal moraine of the 13-mile (21 km) Yalung glacier at 13,000 feet (4,000 m), the porters were paid off because the route up the glacier was too difficult for them. Yalung Camp was established as a substantial camp from where to acclimatise by climbing many nearby peaks.[21][2] [note 7] Accurate theodolite measurements were taken of features in the vicinity of Kangchenjunga's Yalung, or southwest, face. A supply chain for food for the Sherpas – tsampa and atta – was organised from Ghunsa village two days carry away. Also, plans were made for the future moving of goods from Yalung to a base camp much higher up the glacier.[21]

The trek to Yalung Camp had taken 10 days and when they left after their acclimatisation period there was a four-day trek up the glacier to a base camp to be established at the foot of Kempe's Buttress, at the foot of the route suggested by the reconnaissance of the year before. Because the porters had been paid off the trek to base camp had to be done repeatedly in very poor weather. The left bank (southeastern side) of the glacier was subject to continual avalanches from Talung so they took the right bank even though the ice was very broken there.[23][24]

Attempt via Kempe's Buttress

Kempe's Buttress flanks the eastern side of an icefall that descends Kangchenjunga from about 23,500 feet (7,200 m) to the glacier at 18,000 feet (5,500 m). The top of the buttress is at 19,500 feet (5,900 m) and from there Kempe had thought there might be a feasible way further up the icefall.[note 8][25][26][27] From the top of the Buttress, however, Band and Hardie took two days trying to get onto the icefall itself. Evans and Jackson joined the effort and although they then managed to get onto the icefall they could make no further progress. Band, who had climbed Everest's Khumbu Icefall, wrote:

We spent two days of the most exhilarating ice-climbing of our lives, trying to find a route through ... it made the Khumbu Icefall look like a children’s playground … Were we to be defeated so soon?

Fortunately, Hardie spotted a small glacier descending the Western Buttress, the wall on the far side of the glacier and reaching down from a location they called the "Hump" to a point on the icefall roughly level with their position.[note 9] So, they decided to abandon their present attempt and try all over again hoping to reach the western side of the icefall. The intention was to climb up to the Hump along the western side of the Western Buttress and to achieve this involved moving base camp.[30]

| Attempt starting at Kempe's Buttress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Altitude[note 10] | Date occupied (1955) |

Description | |

| feet | metres | |||

| Base | 18,000[31] | 5,500[31] | 12 April[31] | Kempe's second base camp[31] |

| Camp 1 | 19,500[32] | 5,900 | 19 April[33] | Top of Kempe's buttress[note 11] |

| high point | 20,000[35] | 6,100 | 22 April[36] | Height reached on this route by 1955 party. They descended after observing an alternative route.[36] |

Attempt from Pache's grave

Lower slopes

As it happens the location of the second base camp was where, on Crowley's 1905 expedition, Alexis Pache and three porters were laid to rest after they had been killed in an avalanche. The wooden cross and gravestone still stood there.[36][37] Kempe's team had investigated the area the previous year but considered it would tend to lead towards Kangchenjunga West leaving a difficult traverse to the main summit. Also, the route was vulnerable to avalanches.[38][39][28]

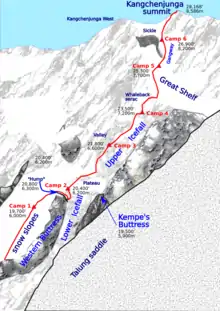

Evans' plan was to climb to the Hump and then drop down to the Lower Icefall. They would then attempt the short climb to the top of the Lower Icefall to reach a plateau at the foot of the Upper Icefall. From there the Great Shelf – a snow shelf cutting across the Yalung Face from about 23,500 feet (7,200 m) in the southeast to 25,500 feet (7,800 m) in the northwest – should lead to a dark rock cirque, the "Sickle", beside a steep snow gangway leading to within striking distance of the summit.[note 12][41] The rocks of the Sickle were the first outcrop to be reached after the Hump.[42]

| Locations of camps | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camp | Altitude[note 10] | Date occupied (1955) |

Description | |

| feet | metres | |||

| Base | 18,100[43] | 5,500 | 23 April[44] | at Pache's Grave[44] |

| Camp 1 | 19,700[45] | 6,000 | 26 April[46] | above the "narrows"[45] |

| Camp 2 | 20,400[45] | 6,200 | 28 April[47] | on the "Plateau" above Lower Icefall[46] |

| Camp 3 | 21,800[45] | 6,600 | 4 May[note 13][48] | Advanced Base camp at the "Valley" below Upper Icefall[49][50] |

| Camp 4 | 23,500[45] | 7,200 | 12 May[49] | above Upper Icefall, level with and before Great Shelf[51] |

| Camp 5 | 25,300[45] | 7,700 | 13 May[52] | ledge below ice cliff at foot of "Sickle" and "Gangway".[53] |

| Camp 6 | 26,900[45] | 8,200 | 24 May[52] | small site dug out halfway up "Gangway"[52] |

| Summit | 28,168[1] | 8,586 | 25 May[note 14][54] | stopped five feet below summit.[55] |

Lower and upper icefall

By 26 April Band and Hardie had pitched Camp 1 two-thirds of the way up the very steep snow slopes on the western side of the Western Buttress. To go higher involved crossing a crevasse 20 feet (6.1 m) wide which was eventually made suitable for Sherpas with a ladder and 200 feet (61 m) of ropes. Up to the Hump and down the ramp on the other side the slopes were about 40° and the descent to the icefall was a drop of some 400 feet (120 m). They struggled up the edge of the icefall to reach the spacious avalanche-free plateau[note 15] between the Upper and Lower Icefall. The Plateau was an excellent location for Camp 2 which was soon established by Evans and Brown.[56][57] For three weeks without a single day being missed, supplies were ferried between Base Camp and Camp 2, stopping overnight at Camp 1 on the way up.[58]

On 29 April Evans and Brown were close to the eventual site of Camp 3 but that night a storm hit and they tried to descend to Camp 1 but the depth of snow and the severe avalanches meant they had to go back to Camp 2 where they were short of food. It was only on 4 May they could reach the site for Camp 3 – by 9 May it was fully equipped as Advance Base Camp at 21,800 feet (6,600 m) by teams of Sherpas and climbers ferrying up and down the mountain.[59] On 12 May Evans and Hardie set up Camp 4 and next day they were able to attain the Great Shelf where there were good snow conditions and they went on to find a suitable location for Camp 5, sheltered by an ice cliff at 25,300 feet (7,700 m), the greatest height ever reached on the mountain.[60]

Upper camps

Streather, Mather and their Sherpas started stocking Camp 4 while the rest of the climbers returned to recuperate at Base Camp. When there, Evans announced the detailed plans for the next few days – the reconnaissance had turned into a bid for the summit. Jackson, McKinnon and their Sherpas would stock Camp 5. Brown and Band, the first summit pair, supported by Evans, Mather and four Sherpas would follow a day later. The supporting climbers would establish Camp 6 as near to the top of the Gangway as possible. Hardie and Streather would be a second assault team, supported by two Sherpas and moving up a day later still.[61]

Things did not get off to a good start. Streather became snowblind and was unable to get above Camp 4 and many of the supplies had to be dumped below Camp 5. Jackson and McKinnon were unable to descend to Camp 3 so had to stay at Camp 4 with Brown and Band. That night a blizzard developed and it seemed the monsoon might be imminent. However, Jackson and McKinnon were able to descend to Camp 3. On the third day the storm conditions abated so Evans, Mather, Brown, Band and three Sherpas set off for Camp 5 only to find an avalanche has swept away many of the supplies that had been dumped there. After a day of unscheduled rest at Camp 5 they then made good progress but when they reached a rocky outcrop at the planned height for Camp 6, 26,900 feet (8,200 m), there was nowhere at all suitable. They had to dig a ledge out of the 45° snow slope where, after two hours work, they created a ledge 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 m) wide for a tent 5 feet (1.5 m) wide. Despite the conditions they had an evening meal of asparagus soup, lambs' tounges and drinking chocolate. Band and Brown remained at Camp 6 for the night of 24 May, wearing all their clothes, including boots, inside their sleeping bags and using a low flow of supplemental oxygen.[62][63]

Summit attempts

| Kangchenjunga expedition videos | |

|---|---|

Marking the 65th anniversary of the first ascent of Kangchenjunga. In particular an interview with Joe Brown (2m30s–11m30s)[64] | |

(no sound) Background information in Horrell (2018). | |

Report of 2011 expedition by Gatta (2011). |

25 May 1955 – Brown and Band

At 05:00 a fine day beckoned and by 08:15 Brown and Band were ready to set off up the Gangway where they found very good snow conditions.[65][66] Going to the top of the Gangway would have led to an awkward lengthy route along the west ridge to the summit so their plan was to veer to the right off the Gangway onto the southwest face and so reach the ridge quite close to the summit. A suitable line had been spotted from below but it was unclear where to actually turn off the Gangway. In the event they turned too soon and had to backtrack, so wasting 1½ hours. The next stage involved rock climbing and then there was a 60° snow slope. They could only afford to use a low rate of oxygen (two litres a minute each) and this seemed to sustain Brown better than Band so they stopped alternating the lead climbing and Brown stayed going first. After over five hours of continuous climbing they reached the ridge and the summit pyramid could be seen 400 feet (120 m) above.[67]

They took a brief rest and a snack until 14:00 when they had two hours of oxygen left – they had to reach the summit by 15:00 to avoid an emergency bivouac on the way down. Brown led a final rock climb up a 20-foot (6 m) tall crack with a slight overhang at the top (grade about "very difficult" ignoring the altitude [68]). This required oxygen at six litres a minute and the climb led to a stance from where, to their surprise, the actual summit was just 20 feet (6 m) away and five feet (1.5 m) higher up. It was 14:45 on 25 May 1955.[69][70] Even though this was the first ascent of the mountain, as agreed they did not go up onto the summit itself.[71] There was a layer of cloud at 20,000 feet (6,100 m) so they could only see the highest peaks – Makalu,[note 16] Lhotse and Everest, 80 miles (130 km) away to the west.[69]

They started the descent, discarding their oxygen sets when they were empty after one hour. As it got dark they reached their tent to be greeted by Hardie and Streather who had arrived there to make a second attempt if the first had failed. Band and Brown thought it was too dangerous to continue straight down to Camp 5 so that night four men had to survive in the small two-man tent that jutted out over the edge of the narrow ledge cut into the steep slope.[73] Brown was in great pain through the night suffering from snowblindness.[73][74]

26 May 1955 – Hardie and Streather

Next morning Hardie and Streather decided a second summit attempt was worthwhile so they set off along the same route but avoiding the previous pair's detour. At the rock wall immediately before the summit Brown and Band had left a sling hanging to help them climb but Hardie and Streather continued further around the base of the wall and found an easy snow slope up to just below the summit which they reached at 12:15.[75][76] They spent an hour at the top before descending successfully. Hardie and Streather had taken 2400 litres of oxygen each compared to Band and Brown's 1600 litres but unfortunately a couple of mishaps led to about half of it leaking away and Streather ended up having to descend without supplementary oxygen. They stayed at Camp 6 overnight and next day continued down to Camp 5 to be met by Evans and Dawa Tensing who had been waiting there to support both pairs of climbers attempting the summit.[77][78]

Departure

Pemi Dorje, one of the Sherpas and Dawa Tenzing's brother-in-law, died at base camp on 26 May. On 19 May he had fallen into a crevasse and become exhausted helping with the carry to Camp 5 and, although he got safely down to base camp and initially appeared to be recovering, he sadly died.[79][80][81] As the various parties started to come down the mountain snow and ice were rapidly melting leaving some snow bridges and ladders in an increasingly dangerous state. Evans decided to leave the mountain quickly only taking equipment that could be readily carried and abandoning the rest. By 28 May the expedition had left the mountain.[82]

On the initial march-in, to avoid high passes that might be snowbound, they had left the Singalila Ridge quite far south at Phulat to head down into the jungle of Nepal. On the return march in heavy rain they went up onto the ridge further north, after Ramser, and followed along the crest to avoid leeches infesting the valleys at the time of the monsoon.[83][20][note 17] On 13 June they were back at Darjeeling[85]

Assessment

In a 1956 American Alpine Journal editorial Francis Farquhar said[86]

The ascent of Kangchenjunga last year by the party led by Charles Evans deserves a good deal more acclaim than seems to have been accorded it. In several respects it was a greater mountaineering achievement than the ascent of Everest. Although not quite the highest mountain in the world it is so close to it as to be definitely in the same pre-eminent class. But in sheer magnitude, in the vastness of its quadruple system of glaciers, in its enormous cliffs, and in its interminable ridges, it is unequalled on the earth’s surface. Moreover, until Evans undertook to solve its problems last year it seemed as if it might be the one great mountain in the world that could not be climbed.

Over fifty years later Doug Scott, who had climbed Mount Everest and Kangchenjunga, wrote it was[5]

... a remarkable climb and one of the finest achievements in the annals of British mountaineering. ... The first ascent of Everest was a remarkable achievement but what made the climbing of Kangchenjunga even more impressive was that on Everest only 900 ft of the ascent route remained unexplored since the Swiss had got so high the year before. On Kangchenjunga there was 9000 ft of untested ground to negotiate and this was found to be more technically difficult than on Everest, with most of the difficulties near the summit.

The expedition was little reported on in the newspapers and none of the team received national honours at the time. Evans' and Band's publications did not encourage any of the usual nationalist feelings: their reports made no mention of flags placed on the summit.[75][87] In 2005 Ed Douglas wrote for the British Mountaineering Council: "In 1955 British climbers made the first ascent of Kangchenjunga, a mountain with an even more formidable reputation than Everest. The nation may have forgotten a unique sporting achievement ...".[88]

Right back in 1956 Evans was prescient when he wrote of the Sherpas he so much admired:[89]

It would be naive to suppose that they can never change. Except those of the strongest character, it is unlikely that they can be proof against the great growth of Himalayan travel, and the penetration into the remotest places of caravans whose assumption is that it is money that matters. We are lucky to have enjoyed their friendship in days when they have not yet been much exposed to the chance of harm.

Notes

- Crowley describes the 1905 expedition in The Confessions of Aleister Crowley.[6]

- Kempe (1955) describes the 1954 expedition.

- Dawa Tensing is not to be confused with Tenzing Norgay who had also been on the 1952 Swiss and 1953 British Everest expeditions.

- Sherpas named were: Dawa Tensing, Annullu, Aila, Ang Dawa (from Kunde), Ang Dawa (from Namche Bazaar), Ang Norbu, Ang Temba, Changjup, Da Tsering, Gyalgen, Hlakpa Sonar, Ila Tenzing, Lobsang, Mingma Tenzing, Pasang Sonar, Phurchita, Pemi Dorje, Tashi, Topke, Urkien.[10]

- Doug Scott wrote: The expedition was brilliantly led by Charles Evans who created a wonderful team effort that put George [Band] and Joe Brown in position to make the first ascent ... to within 10 ft of the summit. There they stopped, in deference to the people of Sikkim who had requested that the climbers not disturb the protecting deities that they said dwelt on the summit.[5]

- From Darjeeling to Kangchenjunga in a direct line is some 46 miles (74 km) but the party's route was twice as long.[18][19]

- Jannu and Kabru were particularly conspicuous from Yalung Camp but these mountains were not climbed.[22]

- Band says the Upper Icefall is 3,500 feet (1,100 m) and the Lower 2,000 feet (610 m) high descending to the Yalung Glacier at 18,000 feet (5,500 m). Kempe estimated the altitude of the top of Buttress at 20,000–21,000 feet (6,100–6,400 m) whereas Evans says 19,500 feet (5,900 m).

- Braham says this ramp was spotted on the 1954 reconnaissance from the slopes of Talung Peak.[28] The 1955 party estimated the altitude of the pass over the Hump as 20,500 feet (6,200 m).[29]

- Altitudes in metres calculated from referenced figures in feet.

- Kempe's high point (but estimated by Kempe at 20,000–21,000 feet (6,100–6,400 m).[34][27].

- The Great Shelf, Gangway and Sickle can all be clearly seen from Darjeeling.[40]

- Established 9 May

- Second party summited 26 May 1955.

- The Plateau was about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) long and 0.25 miles (0.40 km) wide.

- Although the British team knew about the ongoing French expedition to Makalu, they did not know Makalu had been successfully climbed ten days earlier.[72]

- Crowley has a good deal to say about the leeches in this region.[84]

References

Citations

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 321.

- Evans (1956), p. 2.

- Band (1955), pp. 211–212.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 238–241.

- Scott (2012), pp. 287–288.

- Crowley (1969), chapters 51–52.

- Braham (1996), pp. 33–35.

- Side (1955), pp. 83–95.

- Bauer (1932), p. 20, inserted at page 20 in the pdf but at page 176 in printed edition.

- Evans (1956), pp. 6–8,14,91,96.

- Band (1996), pp. 208–210.

- Band (1955), pp. 210–211,220.

- Evans (1956), pp. 162–163.

- Evans (1956), pp. 97–98.

- Band (1955), pp. 220–221.

- Evans & Band (1956), p. 2.

- Evans (1956), p. 13.

- Band (1955), p. 211.

- Evans (1956), p. 15.

- Band (1955), p. 212.

- Band (1955), pp. 213–214.

- Evans (1956), pp. 19,23.

- Evans & Band (1956), pp. 2–3.

- Band (1955), pp. 214–216.

- Band (1955), p. 215.

- Evans (1956), p. 34.

- Kempe (1955), p. 430.

- Braham (1996), p. 34.

- Evans & Band (1956), p. 6.

- Band (1955), pp. 216–218.

- Evans (1956), p. 41.

- Evans (1956), p. 6.

- Evans (1956), p. 48.

- Evans (1956), p. 43.

- Evans (1956), pp. 43,55.

- Evans (1956), p. 55.

- Band (1955), p. 218.

- Kempe (1955), pp. 428–431.

- Evans (1956), p. 8.

- Evans (1956), p. 12.

- Evans (1956), pp. 5–6,54.

- Evans (1956), p. 114.

- Band (1955), p. 217.

- Evans (1956), p. 58.

- Evans (1956), p. 57.

- Evans (1956), p. 60.

- Evans (1956), pp. 56,65.

- Evans (1956), pp. 72,80.

- Band (1955), p. 219.

- Evans (1956), p. 73.

- Evans (1956), p. 85.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 323.

- Evans (1956), p. 89.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), pp. 324–325.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 325.

- Band (1955), pp. 217–218.

- Evans (1956), pp. 6,56–65.

- Evans (1956), p. 71.

- Evans (1956), pp. 67–80.

- Band (1955), pp. 219–220.

- Band (1955), p. 220.

- Band (1955), pp. 220–223.

- Evans (1956), pp. 117–118.

- Alpine Club (2020).

- Band (1955), p. 223.

- Alpine Club (2020), 2 min 30 sec.

- Band (1955), pp. 223–224.

- Alpine Club (2020), 6 min 40 sec.

- Band (1955), pp. 224–225.

- Evans (1956), p. 127.

- Scott (2012), p. 288.

- Evans (1956), p. 136.

- Band (1955), p. 225.

- Alpine Club (2020), 9 min 20 sec.

- Isserman & Weaver (2008), p. 326.

- Band (1955), p. 226.

- Band (1955), pp. 225–226.

- Streather (1996), p. 41.

- Evans (1956), pp. 138–139.

- Band (1955), pp. 221,226.

- Evans & Band (1956), p. 7.

- Evans (1956), p. 141.

- Evans (1956), p. 143.

- Crowley (1969), chapter 52.

- Evans (1956), p. 144.

- Farquhar (1956).

- Barnett (2005).

- Douglas (2005).

- Evans (1956), p. 146.

Works cited

- Alpine Club: Smith, Nick (presenter); Dickinson, Leo; Brown, Joe; Conefrey, Mick; Jackson, Stevan; Kaltenbrunner, Gerlinde (11 June 2020). A Kangchenjunga Special. Alpine ClubCast 9: A Kangchenjunga Special. Alpine Club.

- Band, George (1955). "Kangchenjunga Climbed" (PDF). Alpine Journal. 60: 207–226.

- Band, George (1996). "Kangchenjunga Revisited 1955–1995" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 207–226.

- Barnett, Shaun (May–June 2005). "The Forgotten Climb". New Zealand Geographic (073).

- Bauer, Paul (1932). "Kangchenjunga,1931: the Second Bavarian Attempt" (PDF). Alpine Journal. 44: 13–24.

- Braham, Trevor (1996). "Kangchenjunga: The 1954 Reconnaissance" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 33–35.

- Crowley, Aleister (1969). "Chapter 51–52". The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography. Part Three: The Advent of the Aeon of Horus.

- Evans, Charles (1956). Kangchenjunga, the Untrodden Peak. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Evans, Charles; Band, George (March 1956). "Kangchenjunga Climbed". Geographical Journal. 122 (1): 1–12. doi:10.2307/1791469. JSTOR 1791469.

- Douglas, Ed (22 May 2005). "A Quiet Triumph". British Mountaineering Council.

- Farquhar, Francis P. (1956). "Success on Kangchenjunga Editorial". American Alpine Journal. 10 (1).

- Gatta, Philippe (2011). "The 2011 Kangchenjunga Expedition". Kangchenjunga (8,586 m), Southwest Face Himalaya, Nepal.

- Horrell, Mark (11 April 2018). "Archive footage of the 1955 first ascent of Kangchenjunga". Footsteps on the Mountain.

- Isserman, Maurice; Weaver, Stewart (2008). "The Golden Age of Himalayan Climbing". Fallen Giants : A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire to the Age of Extremes (1 ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300115017.

- Kempe, John (1955). "Kangchenjunga Reconnaissance, 1954" (PDF). Alpine Journal. 59: 428–431.

- Scott, Doug (2012). "Obituary: George Band OBE 2 February 1929—26 August 2011". Geographical Journal. 178 (3): 287–288. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 23263291.

- Side, Douglas (1955). "Towards Kangchenjunga" (PDF). Alpine Journal. 60: 83–95.

- Streather, Tony (1996). "Dawa Tenzing: A Great Sherpa" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 41–53.

Further reading

- Catterall, Peter, ed. (1996). "A Kangchenjunga Seminar" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 15–30.

- Conefrey, Mick (22 May 2020). The Last Great Mountain: The First Ascent of Kangchenjunga. Michael Conefrey. ISBN 9781838039622. and an accompanying article Conefrey, Mick (25 May 2020). "Kangchenjunga - The Last Great Mountain". UKClimbing.

- Freshfield, Douglas W. (April 1902). "The Glaciers of Kangchenjunga" (PDF). Geographical Journal. 19 (4): 453–472. doi:10.2307/1775242.

- Horrell, Mark (21 November 2012). "Joe Brown provides a rare glimpse of Kangchenjunga". Footsteps on the Mountain. Mark Horrell.

- Morrow, Baiba; Morrow, Pat (1999). Footsteps in the clouds: Kangchenjunga a century later. Vancouver: Raincoast Books. ISBN 9781551922263.

- Scott, Doug (1996). "Kangchenjunga 1979" (PDF). Alpine Journal: 44–49.

- Stirling, Sarah (25 May 2020). "First Ascent of Kanchenjunga: 65 years ago this week". British Mountaineering Council.