Gangtok

Gangtok (/ˈɡæŋtɒk/ (![]() listen), Nepali: [ˈgantok]) is a city, municipality, the capital and the largest town of the Indian state of Sikkim. It is also the headquarters of the East Sikkim district. Gangtok is in the eastern Himalayan range, at an elevation of 1,650 m (5,410 ft). The town's population of 100,000 are from different ethnicities such as Bhutia, Lepchas and Indian Gorkhas. Within the higher peaks of the Himalaya and with a year-round mild temperate climate, Gangtok is at the centre of Sikkim's tourism industry.

listen), Nepali: [ˈgantok]) is a city, municipality, the capital and the largest town of the Indian state of Sikkim. It is also the headquarters of the East Sikkim district. Gangtok is in the eastern Himalayan range, at an elevation of 1,650 m (5,410 ft). The town's population of 100,000 are from different ethnicities such as Bhutia, Lepchas and Indian Gorkhas. Within the higher peaks of the Himalaya and with a year-round mild temperate climate, Gangtok is at the centre of Sikkim's tourism industry.

Gangtok | |

|---|---|

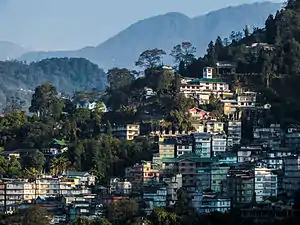

A view of Gangtok from nearby Ganesh Tok point | |

Gangtok Location of Gangtok in Sikkim  Gangtok Gangtok (India)  Gangtok Gangtok (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 27.33°N 88.62°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Sikkim |

| District | East Sikkim |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Body | Gangtok Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Shakti Singh Choudhary[1] (SDF) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 19.2 km2 (7.4 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,650 m (5,410 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 100,290 |

| • Density | 5,223/km2 (13,530/sq mi) |

| Languages[3][4] | |

| • Official | |

| • Additional official | |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 737101 |

| Telephone code | 03592 |

| Vehicle registration | SK-01 |

| Website | gmcsikkim |

Gangtok rose to prominence as a popular Buddhist pilgrimage site after the construction of the Enchey Monastery in 1840. In 1894, the ruling Sikkimese Chogyal, Thutob Namgyal, transferred the capital to Gangtok. In the early 20th century, Gangtok became a major stopover on the trade route between Lhasa in Tibet and cities such as Kolkata (then Calcutta) in British India. After India won its independence from Britain in 1947, Sikkim chose to remain an independent monarchy, with Gangtok as its capital. In 1975, after the integration with the union of India, Gangtok was made India's 22nd state capital.

Etymology

The precise meaning of the name "Gangtok" is unclear, though the most popular meaning is "hill cut".[5]

History

Like the rest of Sikkim, not much is known about the early history of Gangtok.[6] The earliest records date from the construction of the hermitic Gangtok monastery in 1716.[7] Gangtok remained a small hamlet until the construction of the Enchey Monastery in 1840 made it a pilgrimage center. It became the capital of what was left of Sikkim after an English conquest in the mid-19th century in response to a hostage crisis. After the defeat of the Tibetans by the British, Gangtok became a major stopover in the trade between Tibet and British India at the end of the 19th century.[8] Most of the roads and the telegraph in the area were built during this time.

In 1894, Thutob Namgyal, the Sikkimese monarch under British rule, shifted the capital from Tumlong to Gangtok, increasing the city's importance. A new grand palace along with other state buildings was built in the new capital. Following India's independence in 1947, Sikkim became a nation-state with Gangtok as its capital. Sikkim came under the suzerainty of India, with the condition that it would retain its independence, by the treaty signed between the Chogyal and the then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.[9] This pact gave the Indians control of external affairs on behalf of Sikkimese. Trade between India and Tibet continued to flourish through the Nathula and Jelepla passes, offshoots of the ancient Silk Road near Gangtok. These border passes were sealed after the Sino-Indian War in 1962, which deprived Gangtok of its trading business.[10] The Nathula pass was finally opened for limited trade in 2006, fuelling hopes of economic boom.[11][12]

In 1975, after years of political uncertainty and struggle, including riots, the monarchy was abrogated and Sikkim became India's twenty-second state, with Gangtok as its capital after a referendum. Gangtok has witnessed annual landslides, resulting in loss of life and damage to property. The largest disaster occurred in June 1997, when 38 were killed and hundreds of buildings were destroyed.[13]

Geography

Gangtok is located at 27.3325°N 88.6140°E (coordinates of Gangtok head post office).[2] It is situated in the lower Himalayas at an elevation of 1,650 m (5,410 ft).[14] The town lies on one side of a hill, with "The Ridge",[8][15] a promenade housing the Raj Bhawan, the governor's residence, at one end and the palace, situated at an altitude of about 1,800 m (5,900 ft), at the other. The city is flanked on east and west by two streams, namely Roro Chu and Ranikhola, respectively.[13] These two rivers divide the natural drainage into two parts, the eastern and western parts. Both the streams meet the Ranipul and flow south as the main Ranikhola before it joins the Teesta at Singtam.[13] Most of the roads are steep, with the buildings built on compacted ground alongside them.[16]

Most of Sikkim, including Gangtok, is underlain by Precambrian rocks which contains foliated phyllites and schists; slopes are therefore prone to frequent landslides.[17] Surface runoff of water by natural streams (jhora) and man-made drains has contributed to the risk of landslides.[13] According to the Bureau of Indian Standards, the town falls under seismic zone-IV (on a scale of I to V, in order of increasing seismic activity), near the convergent boundary of the Indian and the Eurasian tectonic plates and is subject to frequent earthquakes. The hills are nestled within higher peaks and the snow-clad Himalayan ranges tower over the town from the distance. Mount Kanchenjunga (8,598 m or 28,208 ft)—the world's third-highest peak—is visible to the west of the city. The existence of steep slopes, vulnerability to landslides, large forest cover and inadequate access to most areas have been a major impediment to the natural and balanced growth of the city.[13]

There are densely forested regions around Gangtok, consisting of temperate, deciduous forests of poplar, birch, oak, and elm, as well as evergreen, coniferous trees of the wet alpine zone.[17] Orchids are common, and rare varieties of orchids are featured in flower shows in the city. Bamboos are also abundant. In the lower reaches of the town, the vegetation gradually changes from alpine to temperate deciduous and subtropical.[17] Flowers such as sunflower, marigold, poinsettia, and others bloom, especially in November and December.

Climate

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

29.9 (85.8) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 16.4 (61.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.0 (75.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

13.9 (57.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

16.4 (61.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

1.3 (34.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.4 (34.5) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

10.8 (51.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 27.1 (1.07) |

72.2 (2.84) |

126.4 (4.98) |

296.9 (11.69) |

496.4 (19.54) |

609.8 (24.01) |

626.3 (24.66) |

565.9 (22.28) |

438.7 (17.27) |

173.4 (6.83) |

37.9 (1.49) |

19.5 (0.77) |

3,490.4 (137.42) |

| Average rainy days | 2.4 | 5.4 | 9.2 | 15.2 | 20.1 | 23.6 | 27.0 | 24.7 | 20.8 | 8.4 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 161.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 77 | 78 | 76 | 78 | 85 | 89 | 92 | 92 | 90 | 83 | 79 | 77 | 83 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[18][19][20] | |||||||||||||

Gangtok features a monsoon-influenced subtropical highland climate (Köppen: Cwb). Because of its elevation and sheltered environment, Gangtok enjoys a mild, temperate climate all year round. Like most Himalayan towns, Gangtok has five seasons: summer, monsoons, autumn, winter, and spring. Temperatures range from an average maximum of 22 °C (72 °F) in summer to an average minimum of 4 °C (39 °F) in winter.[21] Summers (lasting from late April to June) are mild, with maximum temperatures rarely crossing 25 °C (77 °F). The monsoon season from June to September is characterised by intense torrential rains often causing landslides that block Gangtok's land access to the rest of the country. Rainfall starts to rise from pre-monsoon in May, and peaks during the monsoon, with July recording the highest monthly average of 649.6 mm (25.6 in).[21] In winter temperature averages between 4 °C (39 °F) and 7 °C (45 °F).[21] Snowfall is rare, and in recent times, Gangtok has received snow only in 1990, 2004, 2005[17] and 2020.[22] Temperatures below freezing are also rare.[17] During this season the weather can be unstable, and change abruptly from bright sunshine and clear skies to heavy rain within a couple of hours. During spring and autumn the weather is generally sunny and mild. Owing to its elevation, Gangtok is often enveloped in fog during the monsoon and winter months.

Banjhakri Falls and Energy Park, Gangtok

Banjhakri Falls and Energy Park, Gangtok River Teesta is the lifeline of Gangtok

River Teesta is the lifeline of Gangtok Gangtok from Tibet Road

Gangtok from Tibet Road An overhead view of Gangtok from the ropeway facility

An overhead view of Gangtok from the ropeway facility

Economy

Gangtok is the main base for Sikkim tourism.[23] Summer and spring seasons are the most popular tourist seasons. Many of Gangtok's residents are employed directly and indirectly in the tourism industry, with many residents owning and working in hotels and restaurants.[24]

Mahatma Gandhi Marg (MG Marg) and Lal Market are prominent business areas and tourist spots in Gangtok.[25]

Ecotourism has emerged as an important economic activity in the region which includes trekking, mountaineering, river rafting and other nature oriented activities.[23] An estimated 351,000 tourists visited Sikkim in 2007, generating revenue of about Rs 50 crores (Rs 500 millions).[24]

The Nathula Pass, located about 50 km (31 mi) from Gangtok, used to be the primary route of the wool, fur and spice trade with Tibet and spurred economic growth for Gangtok till the mid-20th century. In 1962, after the border was closed during the Sino-Indian War, Gangtok fell into recession.[10] The pass was reopened in 2006 and trade through the pass is expected to boost the economy of Gangtok.[23] The Sikkim government is keen to open a Lhasa–Gangtok bus service via Nathula pass.[26] Sikkim's mountainous terrain results in the lack of train or air links, limiting the area's potential for rapid industrial development.[23] The government is the largest employer in the city,[13] both directly and as contractors.

Gangtok's economy does not have a large manufacturing base, but has a thriving Cottage industry in watch-making, country-made alcohol and handicrafts.[23] Among the handicrafts are the handmade paper industry made from various vegetable fibres or cotton rags. The main market in Gangtok provides many of the state's rural residents a place to offer their produce during the harvest seasons. The majority of the private business community is made up of Marwaris and Biharis. As part of Sikkim, Gangtok enjoys the status of being an income-tax free region as per the state's 1948 Income tax law.[27] As Sikkim is a frontier state, the Indian army maintains a large presence in the vicinity of Gangtok. This leads to a population of semi-permanent residents who bring money into the local economy.[28] The Sikkim government started India's first online lottery Playwin to boost government income, but this was later closed by a ruling from the Sikkim High Court.[29]

Agriculture is a large employer in Sikkim and in 2003 the Sikkim state government declared the goal of converting the whole sector to organic production.[30] The goal of 100% organic was achieved in 2016.[30] This achievement offers new export opportunities to grow the agriculture sector, to achieve premium prices and new opportunities for agritourism.[30]

Civic administration

The "White Hall" complex on "The Ridge" houses the residences of the Chief Minister and Governor of Sikkim.

The "White Hall" complex on "The Ridge" houses the residences of the Chief Minister and Governor of Sikkim. Sikkim Legislative Assembly in Gangtok. Fog is common in Gangtok.

Sikkim Legislative Assembly in Gangtok. Fog is common in Gangtok.

Gangtok is administered by the Gangtok Municipal Corporation (GMC) along with the various departments of the Government of Sikkim, particularly the Urban Development and Housing Department (UDHD) and the Public Health Engineering Department (PHED).[13][31] These departments provide municipal functions such as garbage disposal, water supply, tax collection, license allotments, and civic infrastructure. An administrator appointed by the state government heads the UDHD.[32]

As the headquarters of East Sikkim district, Gangtok houses the offices of the district collector, an administrator appointed by the Union Government of India. Gangtok is also the seat of the Sikkim High Court, which is India's smallest High Court in terms of area and population of jurisdiction.[33] Gangtok does not have its own police commissionerate like other major cities in India. Instead, it comes under the jurisdiction of the state police, which is headed by a Director General of Police, although an Inspector General of Police oversees the town.[34] Sikkim is known for its very low crime rate.[35] Rongyek jail in Gangtok is Sikkim's only central jail.[36]

Gangtok is within the Sikkim Lok Sabha constituency that elects a member to the Lok Sabha (Lower House) of the Indian Parliament. The city elects one member in the Sikkim state legislative assembly, the Vidhan Sabha. The Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) won both the parliamentary election in 2009 and the state assembly seat in the 2009 state assembly polls.[37][38]

Utility services

Electricity is supplied by the power department of the Government of Sikkim. Gangtok has a nearly uninterrupted electricity supply due to Sikkim's numerous hydroelectric power stations. The rural roads around Gangtok are maintained by the Border Roads Organisation, a division of the Indian army. Several roads in Gangtok are reported to be in a poor condition,[13] whereas building construction activities continue almost unrestrained in this city lacking proper land infrastructure.[13] Most households are supplied by the central water system maintained and operated by the PHED.[13] The main source of PHED water supply is the Rateychu River, located about 16 km (9.9 mi) from the city, at an altitude of 2,621 m (8,599 ft). Its water treatment plant is located at Selep. The river Rateychu is snow-fed and has perennial streams. Since there is no habitation in the catchment area except for a small army settlement, there is little environmental degradation and the water is of very good quality.[13] 40 seasonal local springs are used by the Rural Management and Development Department of Sikkim Government to supply water to outlying rural areas.

Around 40% of the population has access to sewers.[13] However, only the toilet waste is connected to the sewer while sullage is discharged into the drains.[13] Without a proper sanitation system, the practice of disposing sewage through septic tanks and directly discharging into Jhoras and open drains is prevalent.[13] The entire city drains into the two rivers, Ranikhola and Roro Chu, through numerous small streams and Jhoras. Ranikhola and Roro Chu rivers confluence with Teesta River, the major source of drinking water to the population downstream. The densely populated urban area of Gangtok does not have a combined drainage system to drain out the stormwater and wastewater from the buildings.[13] The estimated solid waste generated in Gangtok city is approximately 45 tonnes.[13] Only around 40% of this is collected by UDHD, while the remainder is indiscriminately thrown into Jhora, streets and valleys.[13] The collected waste is disposed in a dump located about 20 km (12 mi) from the city. There is no waste collection from inaccessible areas where vehicles cannot reach, nor does any system of collection of waste exist in the adjoining rural areas. The city is under a statewide ban on the use of polythene bags.[13]

Transport

Gangtok cable car

Gangtok cable car The Teesta River runs along the National Highway 31A connecting Gangtok to Siliguri.

The Teesta River runs along the National Highway 31A connecting Gangtok to Siliguri. National Highway 31A by the night.

National Highway 31A by the night.

Road

Taxis are the most widely available public transport within Gangtok.[17] Most of the residents stay within a few kilometres of the town centre[39] and many have their own vehicles such as two-wheelers and cars.[40] The share of personal vehicles and taxis combined is 98% of Gangtok's total vehicles, a high percentage when compared to other Indian cities.[17] City buses comprise less than one percent of vehicles.[17] Those travelling longer distances generally make use of share-jeeps, a kind of public taxis. Four wheel drives are used to easily navigate the steep slopes of the roads. The 1 km (0.6 mi) long cable car with three stops connects lower Gangtok suburbs with Sikkim Legislative assembly in central Gangtok and the upper suburbs.[41]

Gangtok is connected to the rest of India by an all-weather metalled highway, National Highway 10,[42] earlier known as National Highway 31A, which links Gangtok to Siliguri, located 114 km (71 mi) away in the neighbouring state of West Bengal. The highway also provides a link to the neighbouring hill station towns of Darjeeling and Kalimpong, which are the nearest urban areas. Regular jeep, van, and bus services link these towns to Gangtok. Gangtok is a linear city that has developed along the arterial roads, especially National Highway 31A.[13] Most of the road length in Gangtok is of two lane undivided carriageway with footpath on one side of the road and drain on the other. The steep gradient of the different road stretches coupled with a spiral road configuration constrain the smooth flow of vehicular as well as pedestrian traffic.[13]

Rail

The nearest railhead connected to the rest of India is the station of New Jalpaiguri (NJP) in Siliguri, situated 124 km (77 mi) via NH10 away from Gangtok. Work has commenced for a broad gauge railway link from Sevoke in West Bengal to Rangpo in Sikkim[43] that is planned for extension to Gangtok.[44]

Air

Pakyong Airport is a greenfield airport near Gangtok, the state capital of Sikkim, India.[45] The airport, spread over 400 ha (990 acres), is located at Pakyong town about 35 km (22 mi) south of Gangtok.[46] At 4500 ft, Pakyong Airport is one of the five highest airports in India.[47] It is also the first greenfield airport to be constructed in the Northeastern Region of India,[48] the 100th operational airport in India, and the only airport in the state of Sikkim.[49][50]

The airport was inaugurated by India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 24 September 2018[51] and the first commercial flight operations from the airport began on 4 October 2018 between Pakyong and Kolkata.[52]

Demographics

| Gangtok population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | %± | |

| 1951 | 2,744 | — | |

| 1961 | 6,848 | 149.6% | |

| 1971 | 13,308 | 94.3% | |

| 1981 | 36,747 | 176.1% | |

| 1991 | 25,024 | −31.9% | |

| 2001 | 29,354 | 17.3% | |

| 2011 | 98,658 | 236.1% | |

| Population 1951–2011.[23] Negative growth attributed to reduction of notified town limits. | |||

According to the Provisional Population Totals 2011 census of India, the population of Gangtok Municipal Corporation has been estimated to be 98,658. Males constituted 53% of the population and females 47%. The Gangtok subdivision of the East Sikkim district had a population of 281,293, Gangtok has an average literacy rate of 82.17%, higher than the national average of 74%: male literacy is 85.33%, and female literacy is 78.68.[53] About 8% of Gangtok's population live in the nine notified slums and squatter settlements, all on Government land. More people live in areas that depict slum-like characteristics but have not been notified as slums yet because they have developed on private land.[54] Of the total urban population of Sikkim, Gangtok Municipal Corporation has a share of 55.5%. Including Gangtok, East District has a share of 88% of the total urban population. The quality of life, the pace of development and availability of basic infrastructure and employment prospects has been the major cause for rapid migration to the city. With this migration, the urban services are under pressure, intensified by the lack of availability of suitable land for infrastructure development.[13]

Ethnic Nepalis, who settled in the region during British rule,[55] comprise the majority of Gangtok's residents. Lepchas, native to the land, and Bhutias also constitute a sizeable portion of the populace.[55] Additionally, a large number of Tibetans have immigrated to the town. Immigrant resident communities not native to the region include the Marwaris,[13] Biharis and Bengalis.

Hinduism and Buddhism are the most significant religions in Gangtok.[23] Gangtok also has a sizeable Christian population and a small Muslim minority.[23] The North East Presbyterian Church, Roman Catholic Church and Anjuman Mosque in Gangtok are places of worship for the religious minorities.[56] The town has not been communalised, having never witnessed any sort of inter-religious strife in its history.[57] Nepali is the most widely spoken language in Sikkim as well as Gangtok.[58] English and Hindi being the official language of Sikkim and India respectively, are also widely spoken and understood in most of Sikkim, particularly in Gangtok.[59][60] Other languages spoken in Gangtok include Bhutia (Sikkimese), Tibetan and Lepcha.

Culture

The Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Museum displays rare Lepcha tapestries, masks and Buddhist statues.

The Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Museum displays rare Lepcha tapestries, masks and Buddhist statues. View of downtown Gangtok city from Crown Prince Tenzing Kunzang Namgyal Walkway.

View of downtown Gangtok city from Crown Prince Tenzing Kunzang Namgyal Walkway. Rumtek Monastery, located on the outskirts of Gangtokone, is one of Buddhism's holiest monasteries.

Rumtek Monastery, located on the outskirts of Gangtokone, is one of Buddhism's holiest monasteries.

Apart from the major religious festivals of Dashain, Tihar, Christmas, Holi etc., the diverse ethnic populace of the town celebrates several local festivals. The Lepchas and Bhutias celebrate new year in January, while Tibetans celebrate the new year (Losar) with "Devil Dance" in January–February. The Maghe sankranti, Ram Navami are some of the important Nepalese festivals. Chotrul Duchen, Buddha Jayanti, the birthday of the Dalai Lama, Loosong, Bhumchu, Saga Dawa, Lhabab Duechen and Drupka Teshi are some other festivals, some distinct to local culture and others shared with the rest of India, Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet.[23][61]

A popular food in Gangtok is the momo,[62] a steamed dumpling containing pork, beef and vegetables cooked in a doughy wrapping and served with watery soup. Wai-Wai is a packaged snack consisting of noodles which are eaten either dry or in soup form. A form of noodle called thukpa,[62] served in soup form is also popular in Gangtok. Other noodle-based foods such as the chowmein, thenthuk, fakthu, gyathuk and wonton are available. Other traditional Sikkimese cuisine include shah-phaley (Sikkimese patties with spiced minced meat in a crisp samosa-like case) and Gack-ko soup.[63] Restaurants offer a wide variety of traditional Indian, continental and Chinese cuisines to cater to the tourists. Churpee, a kind of hard cheese made from cow's or yak's milk is sometimes chewed. Chhang is a local frothy millet beer traditionally served in bamboo tankards and drunk through bamboo or cane straws.[63]

Football (soccer), cricket and archery are the most popular sports in Gangtok.[23] The Paljor Stadium, which hosts football matches, is the sole sporting ground in the city. Thangka—a notable handicraft—is an elaborately hand-painted religious scroll in brilliant colours drawn on fabric hung in a monastery or a family altar and occasionally carried by monks in ceremonial processions.[61] Chhaams are vividly costumed monastic dances performed on ceremonial and festive occasions, especially in the monasteries during the Tibetan new year.[61]

City institutions

Temple of the Maharajas, Gangtok. 1938.

Temple of the Maharajas, Gangtok. 1938. The Himalayan black bear is seen here in the Himalayan Zoological Park.

The Himalayan black bear is seen here in the Himalayan Zoological Park.

A centre of Buddhist learning and culture, Gangtok's most notable Buddhist institutions are the Enchey monastery,[5] the Do-drul Chorten stupa complex and the Rumtek Monastery. The Enchey monastery is the city's oldest monastery and is the seat of the Nyingma order.[56] The two-hundred-year-old baroque monastery houses images of gods, goddesses, and other religious artifacts.[56] In the month of January, the Chaam, or masked dance, is performed with great fanfare. The Do-drul Chorten is a stupa which was constructed in 1945 by Trulshik Rimpoché, head of the Nyingma order of Tibetan Buddhism.[56] Inside this stupa are complete set of relics, holy books, and mantras. Surrounding the edifice are 108 Mani Lhakor, or prayer wheels.[56] The complex also houses a religious school.

The Rumtek Monastery on the outskirts of the town is one of Buddhism's most sacred monasteries. The monastery is the seat of the Kagyu order, one of the major Tibetan sects, and houses some of the world's most sacred and rare Tibetan Buddhist scriptures and religious objects in its reliquary. Constructed in the 1960s, the building is modeled after a similar monastery in Lhasa, Tibet. Rumtek was the focus of international media attention in 2000 after the seventeenth Karmapa, one of the four holiest lamas, fled Lhasa and sought refuge in the monastery.[64][65]

The Namgyal Institute of Tibetology, better known as the Tibetology Museum, houses a huge collection of masks, Buddhist scriptures, statues, and tapestries.[66] It has over two hundred Buddhist icons, and is a centre of study of Buddhist philosophy. The Thakurbari Temple, located in the heart of the city, established in 1935 on a prime piece of land donated by the then Maharaja of Sikkim, is one of the oldest and best-known Hindu temples in the city.[67][68] The Ganesh Tok and the Hanuman Tok, dedicated to the Hindu gods Ganpati and Hanuman and housing important Hindu deities, are located in the upper reaches of the city.[69][70] The Himalayan Zoological Park exhibits the fauna of the Himalayas in their natural habitats. The zoo features the Himalayan black bear, red pandas, the barking deer, the snow leopard, the leopard cat, Tibetan wolf, masked palm civet and the spotted deer, amongst the others.[71] Jawaharlal Nehru Botanical Gardens, near Rumtek, houses many species of orchid and as many as fifty different species of tree, including many oaks.[72]

Education

Gangtok's schools are either run by the state government or by private and religious organizations. Schools mainly use English and Nepali as their medium of instruction. The schools are either affiliated with the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education, Central Board of Secondary Education or the National Institute of Open Schooling. Notable schools include the Tashi Namgyal Academy,[73] Paljor Namgyal Girls School, Holy Cross School, Taktse International School and Kendriya Vidyalaya.[74]

Colleges conferring graduate degrees include Sikkim Government College, Sikkim Government Law College and Damber Singh College.[13] Sikkim University established in 2007 is functioning in Gangtok; the university has been allotted land in neighbouring Yang Yang town for establishment of its own campus. The university offers a diverse range of courses and has a number of institutes affiliated to it. 8 km (5.0 mi) from here is the headquarters of the Sikkim Manipal University, which houses Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences and Sikkim Manipal Institute of Technology.[13] The Indira Gandhi National Open University also has a regional center in the city. There are other institutions offering diplomas in Buddhist literature, catering and other non-mainstream fields.[13] District Institute of Education and Training and State Institute of Education conduct teacher training programs.[75][76]

Media

More than 50 newspapers are published in Sikkim.[77] Multiple local Nepali and English newspapers are published,[78] whereas regional and national Hindi and English newspapers, printed elsewhere in India, are also circulated. The English newspapers include The Statesman and The Telegraph, which are printed in Siliguri; The Hindu and The Times of India, which are printed in Kolkata. Sikkim Herald, the newsweekly of the Government of Sikkim is published in thirteen languages of the state.[77]

Gangtok has two cinema halls featuring Nepali, Hindi and English-language films.[56] The town also has a public library.[56]

The main service providers are Sikkim Cable, Nayuma,[79] Dish TV and Doordarshan. All India Radio has a local station in Gangtok, which transmits various programs of mass interest. Along that, other three fm stations Nine fm, Radio Misty and Red fm are the four radio stations in the city. BSNL, Vodafone, Jio and Airtel have the four largest cellular networks in the town with 4G services available within the city limits. There is a Doordarshan TV station in Gangtok.[80]

See also

References

- "Gangtokmunicipalcorporation.org". Gangtokmunicipalcorporation.org. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "Gangtok, India page". Global Gazetteer Version 2.1. Falling Rain Genomics, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- "1977 Sikkim government gazette" (PDF). sikkim.gov.in. Governor of Sikkim. p. 188. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). 16 July 2014. p. 109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Bannerjee, Parag (14 October 2007). "Next weekend you can be at ... Gangtok". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- Shangderpa, Pema Leyda (6 October 2003). "Kids to learn hill state history". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Bernier, Ronald M. (1997). Himalayan Architecture. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 0-8386-3602-0.

- Lepcha, N.S. "Gangtok Capital Attraction". Himalayan Travel Trade Journal. MD Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 August 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "History of Skkim". sikkim.nic.in. National Informatics Center, Sikkim. Archived from the original on 30 October 2006. Retrieved 20 May 2008.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Jha, Prashant (August 2006). "Special report: A break in the ridgeline". Himal South Asia. South Asia Trust. Archived from the original on 30 October 2006. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- "Historic India-China link opens". BBC News. 6 July 2006. Archived from the original on 7 July 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2006.

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2011). China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2

- "Section 4: City Assessment" (PDF). City Development Plan-Gangtok City. Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Geographical Location". Meteorological Center, Gangtok. India Meteorological Department, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Negi, S. S. (1998). Discovering the Himalaya. Indus Publishing. p. 563. ISBN 81-7387-079-9.

- "Gangtok City". mapsofindia.com. Compare Infobase Limited. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- "Section 2: Introduction To The State And Its Capital" (PDF). City Development Plan-Gangtok City. Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- "Station: Gangtok Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 279–280. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M190. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Gangtok Climatological Table 1971–2000". India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Meteorological data in respect of Gangtok and Tadong station". Meteorological Center, Gangtok. India Meteorological Department, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India. Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- "Gangtok sees snowfall after 15 years » Northeast Today". Northeast Today. 7 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Section 3: Social, Demographic & Economic Profile" (PDF). City Development Plan-Gangtok City. Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Press Trust of India (24 April 2008). "Tourist inflow in Sikkim up 10% in 2007". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- Sen, Piyali (27 January 2020). "Secret Gangtok: 5 Things That No One Will Tell You About". Outlook. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- Sinha, A. C. (September 2005). "Nathula: Trading in uncertainty". Himal South Asia. South Asia Trust. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Atreya, Satikah (4 March 2008). "Decision to exempt incomes of Sikkim subjects hailed". The Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 1 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Mohan, C. Raja (29 June 2003). "Building a gateway to Tibet". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 4 May 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- Shangderpa, Pema Leyda (12 July 2003). "Ducking court blow, Gangtok retailers play to win". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 12 July 2003.

- Paull, John (2017) "Four New Strategies to Grow the Organic Agriculture Sector" Archived 4 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Agrofor International Journal, 2(3):61-70.

- "Introduction". Urban Development and Housing Department. Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- "Section 8: City Management and Institutional Strengthening" (PDF). City Development Plan-Gangtok City. Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Mitta, Manoj (27 December 2006). "Gangtok turns 'kaala paani' for high court judges". The Times of India. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "List of IPS officers and place of posting". Department of Information Technology, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- "Sikkim Police: History". Sikkim police website. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Maps". Prison Statistics India: 2005. National Crime Records Bureau, Government of India. June 2007. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- "Election Result of Sikkim Lok Sabha Constituency". Biographical Sketch, Member of Parliament, 12th Lok Sabha. Indian Parliament, National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Sikkim Assembly Elections 2004 Results". Assembly Elections 2004, Indian-Elections. Election Commission of India. Archived from the original on 10 June 2004. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "City Assessment: Physical Infrastructure" (PDF). City Development Plan-Gangtok City. Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. pp. 4–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "City Assessment: Physical Infrastructure" (PDF). City Development Plan-Gangtok City. Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. pp. 4–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Gangtok ready for ropeway ride". The Telegraph. 26 November 2003. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- Khanna, Rohit (11 August 2015). "Bengal-Sikkim tussle over NH-10". Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "Gangtok". Sikkiminfo website. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Internet Archive Wayback Machine" (PDF). 30 March 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "Sikkim to have 100th functional airport in India". 2 May 2018.

- "Wait for Sikkim air link".

- "Sikkim's Greenfield Airport". Punjlloyd. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "Sikkim's Pakyong airport stuns before it flies". 24 September 2018.

- "Sikkim to get its first airport at Pakyong". The Indian Express. 17 November 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "Pakyong airport in Sikkim to become the 100th functional airport in India: Jayant Sinha". Financial Express. PTI. 3 May 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "PM Narendra Modi inaugurates Sikkim's Pakyong airport". The Economic Times. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Sikkim's Pakyong Airport welcomes first commercial flight in state with water cannon salute". First Post. First Post. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "Population of Sikkim – 2011 census results". populationindia.com. 14 May 2011. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Section 5: Urban Poor and Housing Situation" (PDF). City Development Plan-Gangtok City. Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "People". Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- "Tourism". Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- Dorjee, C. K. (5 December 2003). "The Ethnic People of Sikkim". Features. Press Information Bureau, Government of India. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "People of Sikkim". Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- "Introduction to Sikkim". Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- "Constitution of India as of 29 July 2008" (PDF). The Constitution of India. Ministry of Law & Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "Festivals of Sikkim". Culture. Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- Shangderpa, Pema Leyda (3 September 2002). "Sleepy capital comes alive to beats of GenX". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- Gantzer, Hugh; Colleen Gantzer (11 June 2006). "The seat of esoteric knowledge". Deccan Herald. The Printers (Mysore) Private Ltd. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2008.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Harding, Luke (30 April 2001). "Tibetan leader at crossroads". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Cheung, Susanna Chui-Yung (5 April 2000). "The flight of the Karmapa and the security of South Asia". The Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Museum". Namgyal Institute of Tibetology. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2008.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- "Some Aspect of Bhutia Culture in Sikkim (a Case Study)" (PDF). 18 January 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Silk Route Tour Package". The Weekender Info. 2 March 2019. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Slides snap road links in hill state". The Telegraph. 17 July 2007. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Army lands in row over Baba". The Telegraph. 4 January 2007. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- "Himalayan Zoological Park". Forests, Environment and Forests Management Department, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- "Jawaharlal Nehru Botanical Garden". BharatOnline.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2008.

- Chettri, Naresh (21 April 2011). "Annual Prize Day held at Tashi Namgyal Academy". isikkim.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Kendriya Vidyalaya". Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan. National Informatics Centre (NIC), Government of India. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "District Institute of Education and Training, Gangtok". National Informatics Centre (NIC), Sikkim State Centre. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- "Education Statistics". Sikkim: A Statistical Profile. Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- "About Us". Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

- "Newspapers in Sikkim". Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Shangderpa, Pema Leyda (28 January 2003). "Bhandari adds political colour to cable war". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- "Facts and Figures about Sikkim". Government of Sikkim. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gangtok. |

Gangtok travel guide from Wikivoyage

Gangtok travel guide from Wikivoyage- Gangtok at the Encyclopædia Britannica