1972 in the Vietnam War

1972 in the Vietnam War saw foreign involvement in South Vietnam slowly declining. Two allies, New Zealand and Thailand, which had each contributed military contingents, left South Vietnam this year. The United States continued to participate in combat, primarily with air power to assist the South Vietnamese army, while negotiators in Paris tried to hammer out a peace agreement and withdrawal strategy for the United States.

| 1972 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) B-52 bombing run | |||

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Strength | |||

|

South Vietnam: 1,048,000 | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

|

US: 641 killed [1] South Vietnam: 39,587 killed[2]:275 | 120,000 - 160,000 killed | ||

January

- 1 January

U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam numbered 133,200, a reduction from more than 500,000 in 1968.[3]

- 10 January

The Cambodian Khmer National Army (ANK) withdrew from the town of Ponhea Kraek (Krek) near the Fishhook abandoning the last remaining road link between Cambodia and South Vietnam. Further south in the Parrot's Beak the South Vietnamese Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) began Operation Prek Ta against the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) in that area of Cambodia. The objective of the offensive was to disrupt the preparations of the North Vietnamese for an anticipated offensive on Tết, 15 February.[4]

- 12 January

Le Duc Tho, Politburo member and secret negotiator for North Vietnam in the Paris peace talks, cabled the head of Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) in South Vietnam that "we and the enemy are preparing for a ferocious confrontation ... during the upcoming spring and summer." In addition to supporting the PAVN troops in South Vietnam, Tho instructed COSVN to devote attention to attacking the Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS) pacification program] and to the political struggle in the cities of South Vietnam.[5]

- 13 January

President Richard Nixon announced that 70,000 American troops would be pulled out of South Vietnam by 1 May, cutting the existing force of 139,000 by half.[6]

- 16 January

Leaders of 46 Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish organizations met in Kansas City and asked for the withdrawal of American military personnel from South Vietnam and a cut-off in aid to the South Vietnamese government.[7]:55

- 20 January

The head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), General Creighton Abrams cabled Washington that "the enemy [North Vietnam] is preparing and positioning his forces for a major offensive.... There is no doubt this is to be a major campaign." Abrams requested additional authority to use U.S. American air power to mount an effective defense.[5]

- 25 January

President Nixon revealed that National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger had been meeting secretly with North Vietnamese representatives for more than 2 years. He also revealed the U.S. peace plan that had been proposed to Hanoi. Nixon proposed that, within six months of an agreement, all U.S. military be withdrawn from South Vietnam, Prisoners of War exchanged, an internationally supervised cease fire implemented, and a presidential election held in South Vietnam. Nixon did not demand the withdrawal of North Vietnamese military forces from South Vietnam.[8]

- 28 January

In a performance at a White House gala dinner by the Ray Conniff Singers, one of the singers, Carole Feraci, held up a banner reading "Stop the Killing" and said "President Nixon, stop bombing human beings, animals and vegetation. You go to church on Sundays and pray to Jesus Christ, if Jesus Christ were here tonight, you would not dare to drop another bomb."[9]

- 31 January

North Vietnam criticized the U.S. for making public the details of secret peace talks. North Vietnam introduced its peace plan which demanded the immediate and unconditional withdrawal of U.S. military personnel from South Vietnam and the resignation of the Thieu government.[10]

February

- 4 February

President Nixon approved additional authority to General Abrams in South Vietnam to use American power to counter the anticipated North Vietnamese offensive. Specifically, the President acknowledged the growing threat from North Vietnamese surface-to-air missiles (SAM) and authorized the United States Air Force (USAF) to strike against SAM sites in the southern part of North Vietnam and neighboring Laos.[11]

The last of Thailand's 12,000 troops in South Vietnam depart to return home.[12]:298

- 5 February

President Nixon ordered the draw down of USAF assets halted and the reassignment (Operation Bullet Shot) of 150 B-52 heavy bombers to Andersen Air Force Base in Guam and U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield in Thailand in anticipation of the PAVN offensive in South Vietnam.[13]

- 6 February - 17 March

Operation Strength was an RLA offensive against PAVN forces in northern Laos to drawn forces away from besieging Long Tieng.[14]:335–6

- 10 February

U.S. and Republic of Vietnam Air Force (RVNAF) aircraft completed a 24-hour period of bombing strikes against North Vietnam, with almost 400 bombing strikes carried out.[15]

- 11 February

G. McMurtrie Godley, U.S. Ambassador to Laos, responded negatively to a proposal by the White House, Defense Department, State Department and CIA that Laotian and Thai troops and American CIA operatives be withdrawn from Long Tieng, the headquarters of Laotian resistance to the communist Pathet Lao and PAVN. Godley argued that withdrawing from Long Tieng would plunge the United States into "an abyss" and be "a dramatic military setback and political disequilibrium at the time of the President's visit to Peking.[16]

- 11 February - 31 March

Operation Sinsay was a planned RLA offensive that was pre-empted by a PAVN attack the reached Pakse, but RLA forces were then deployed to attack the PAVN lines of communications forcing their withdrawal.[14]:339–40

- 12 February

Washington responded to Ambassador Godley in Laos conceding that it was "not in position to give you detailed tactical instructions from this distance." The Department of Defense maintained that Godley should be ordered to "thin out" the forces defending Long Tieng. The State Department, CIA, and White House disagreed and left the proposed thinning out to Godley's discretion.[17] Godley chose to defend Long Tieng and the town was held for another three years until the final Communist victory in Laos.

- 13 February

On this day and the five previous days the U.S. conducted the heaviest U.S. bombing raids of the war to date. The targets were PAVN and Viet Cong (VC) bases and infiltration routes into South Vietnam. The bombing was aimed at disrupting PAVN/VC preparations for the anticipated Tết offensive.[18]

- 15 February

The Tết holiday in Vietnam. The anticipated Tết offensive by the PAVN/VC did not occur.

- 16 February

Three U.S. warplanes were shot down over North Vietnam in raids to destroy artillery positions.[12]:300

- 21 February

Nixon arrived in Beijing, China and met with Mao Zedong in the first direct face to face meeting between a Chinese Communist leader and an American President. North Vietnam feared that the Americans and Chinese would come up with a deal disadvantageous to North Vietnam.[12]:300–1 With the relationship of the United States improving with both the Soviet Union and China the Vietnam War "began to seem an irrelevant, troublesome historical leftover that might endanger the new relationships."[19]:28

- 24 February

The North Vietnamese and VC delegations walked out of the Paris Peace Talks in protest at the recent upsurge in U.S. bombing, they would return to the negotiations the following week.[20]

- 29 February

The Republic of Korea (South Korea) completed the withdrawal of its Marine brigade from South Vietnam. Two Republic of Korea Army divisions totaling 36,000 men remained in South Vietnam. The United States financed the South Korean military force.[12]:301[7]:55

March

- 6-31 March

Operation Strength II was an RLA offensive designed to draw PAVN forces away from besieging Long Tieng. The operation failed to divert PAVN forces.[14]:335–9

- 7 March

U.S. bombing of anti-aircraft installations extended up to 120 miles (190 km) north of the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The 86 air raids carried out in North Vietnam so far in 1972 equaled the number of air raids against North Vietnam during all of 1971.[12]:301

- 10 March

Prime Minister Lon Nol declared President of Cambodia.

The U.S. 101st Airborne Division left South Vietnam, the last U.S. ground combat division to be withdrawn from South Vietnam.[21]

- 21 March

The Khmer Rouge bombarded the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh with artillery, killing more than 100 civilians. This was the heaviest attack on Phnom Penh since the Cambodian Civil War began in 1970.[12]:302

- 21 March - 6 October

The Lavelle Affair began when USAF General John D. Lavelle, commander of Seventh Air Force, was accused of breaching the rules of engagement for reconnaissance patrols and protective reaction strikes over North Vietnam, allowing the falsifying of records to show that U.S. aircraft had been fired on and so allowing them to hit North Vietnamese targets. Lavelle would be forced to retire as a Major General.[22]

- 22 March - 30 April

The PAVN 101D Regiment attacked the ARVN 42nd Ranger Group at Kompong Trach in Cambodia. Each side reinforced and the fighting continued until the end of April when the ARVN withdrew having inflicted heavy losses on the PAVN 1st Division. The battle was the first phase of the Easter Offensive in southern Cambodia and the Mekong Delta.[23]:143–5

- 23 March

The United States boycotted peace negotiations in Paris with the North Vietnamese, citing the failure of North Vietnam to negotiate seriously.[24]

- 30 March

The long anticipated offensive by the PAVN/VC began. Called the Nguyễn Huệ Offensive or Chiến dịch Xuân hè 1972 in Vietnamese and the Easter Offensive in English, three PAVN divisions (30,000–40,000 men) with support from tanks and artillery crossed the DMZ or came from Laos to the west to attack the ARVN 3rd Division. Although a North Vietnamese offensive had been expected, the invasion across the DMZ was a surprise and the ARVN was ill-prepared. Several small firebases were overrun within hours.[25]

North Vietnam's military objectives in launching what would be a three-pronged offensive were the capture of the cities of Quang Tri in the northern part of South Vietnam, Kontum in the Central Highlands and An Loc in the south.[24]

April

- 1-27 April

Operation Fa Ngum was an RLA operation to capture the villages of Ban Ngik and Laongam as bases for incursions onto the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The RLA captured Laongam, but were repulsed by the PAVN in their attacks on Ban Ngik.[14]:340–1

- 2 April

ARVN forces numbering about 1,500 soldiers at Camp Carroll, a former United States Marine Corps base a few miles south of the DMZ, surrendered to the PAVN. Camp Carroll was important to South Vietnam because of its M107 175 mm artillery with a range of up to 20 miles (32 km). The capture of Camp Carroll gave the PAVN control of western Quảng Trị Province.[26]

With the city of Đông Hà near the DMZ threatened, Nixon authorized U.S. naval vessels offshore to strike at the PAVN with warplanes and naval gunfire.[24]

Lieutenant Colonel Iceal Hambleton was the sole survivor of an EB-66 shot down near Đông Hà. His rescue was the longest and most costly search and rescue mission during the war resulting in the loss of five aircraft, 11 U.S. killed and two captured.[27]

- 4 April

Nixon authorized increased bombing of PAVN troops in South Vietnam and B-52 strikes against North Vietnam. He said, "These bastards have never been bombed like they're going to be bombed this time."[24]

The PAVN attacked South Vietnamese positions in northern Binh Dinh province from their stronghold in the An Lao Valley. U.S. and South Vietnamese forces had contested the An Lao valley with the PAVN 3rd Division since Operation Masher in January 1966. PAVN/VC forces overran many ARVN positions.[28]:252–9

- 4–7 April

The second prong of the Easter Offensive was the movement across the border from Cambodia of the VC 5th Division and an attack on 4,000 ARVN defenders at the Battle of Loc Ninh. Lộc Ninh was a small district town in Bình Long Province, approximately 75 miles (121 km) north of Saigon. Nearly all of the ARVN defenders were killed or surrendered.[28]:398–420

- 7 April

Proceeding southward from the Lộc Ninh, PAVN/VC soldiers succeeded in surrounding the city of An Lộc, the capital of Bình Long Province and the objective of the southern prong of the Easter Offensive. The defenders of An Lộc would henceforth be supplied and reinforced by air.[28]:423–4

- 9 April

In Washington, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger warned Soviet Ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin that the U.S. might take "drastic measures to end the [Vietnam] war once and for all."[29]:265

- 10 April

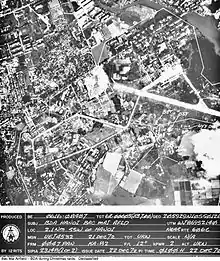

For the first time since November 1968, U.S. B-52s bombed North Vietnam in Operation Freedom Train. Their priority targets were SAM sites. The U.S. called the SAM sites "the most sophisticated air defenses in the history of air warfare.[12]:305

_dropping_bombs_over_Vietnam_c1972.jpg.webp)

- 12 April

A PAVN rocket attack on Da Nang Air Base killed 14 Vietnamese civilians.[30]

- 13 April

The United States Senate voted 68–16 to approve the War Powers Act, which would limit the power of the President to commit American forces to hostilities without Congressional approval. The legislation then moved on to the House.[31]

- 13 April – July 20

After several days of artillery strikes, the PAVN attacked An Lộc with tanks and infantry. They were halted at the city outskirts by ARVN defenders and heavy air attacks by the United States. The Battle of An Lộc became a siege that lasted for 66 days and culminated in a victory for South Vietnam. North Vietnam devoted 35,000 soldiers to the battle and siege. The victory at An Lộc halted the PAVN advance towards Saigon.[32]

- 15–17 April

The U.S. carried out heavy B-52 and fighter bomber strikes against Hanoi and Haiphong in Operation Freedom Porch. Nixon said, "we really left them our calling card this weekend."[29]:266

- 15–20 April

Anti-war demonstrators protested the bombing of North Vietnam throughout the United States. Hundreds of protesters were arrested.[7]:56

- 19 April

_at_Da_Nang%252C_Vietnam%252C_in_April_1972.jpg.webp)

Several Vietnam People's Air Force (VPAF) MiG-17F fighter-bombers attacked United States Navy warships in the Battle of Đồng Hới. This was the first air attack on U.S. warships of the Vietnam War. A gun mount on the USS Higbee was destroyed. The U.S. navy sunk several motor torpedo boats and shot down several VPAF planes and also engaged shore batteries in North Vietnam.[12]:306–7

- 20 April

President Nixon announced that American troops would be reduced in numbers in South Vietnam from 69,000 on this date to 49,000 by 1 July. Many of those being withdrawn from South Vietnam went to Thailand to prosecute the air war from there. USAF strength in Thailand increased from 32,000 to 45,000. In addition, four additional aircraft carriers were stationed off the coast of Vietnam and the number of B-52s stationed in Thailand and Guam was increased from 50 to 200.[19]:19

- 21–25 April

Secretary of State Kissinger visited Moscow and met with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev to prepare for an upcoming summit meeting between Nixon and Brezhnev. Nixon instructed Kissinger that his top priority was to get Soviet cooperation in seeking an agreement to end hostilities in South Vietnam. Brezhnev said he would use Soviet influence but he could not dictate to North Vietnam.[33]:39–42

- 22 April

100,000 people in various cities around the United States protest increased bombing by the US in Vietnam.[12]:307

- 23 April

The PAVN uses AT-3 Sagger anti-tank guided missiles for the first time in combat, attacking the ARVN 20th Tank Regiment destroying one M48A3 and one M113 armored cavalry assault vehicle (ACAV) and damaging a second ACAV.[34]:210

- 23–24 April

After preliminary encounters, the third prong of the Easter Offensive began in the Central Highlands. The PAVN 2nd Division supported by tanks attacked the ARVN 47th Regiment, 22nd Division at Tân Cảnh Base Camp. By nightfall on 24 April, the PAVN had overrun Tan Canh and nearby Dak To II Base Camp and the 22nd Division had disintegrated.[28]:265–84

- 24 April

The U.S. 1st Combat Aerial TOW Team arrived in South Vietnam to test the new BGM-71 TOW anti-armor missile under combat conditions. The team consisted of two UH-1B helicopters each mounting the XM26 TOW weapons system.[34]:215

Da Nang Air Base was hit by PAVN 122mm rockets prompting a call for Marines to provide base security and on 25 May the 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines was deployed to the base.[35]:158–9

- 27 April

The United States Joint Chiefs of Staff assessed the performance of South Vietnamese armed forces thus far in the Easter offensive as "encouraging."[36]

- 28 April

The first kill is made by a PAVN SA-7 Man-portable air-defense system.[37]

- 29 April - 2 May

Approximately 2,000 South Vietnamese civilians are killed by indiscriminate PAVN artillery fire as they fled Quảng Trị along Highway 1.[35]:84–5

May

- 1 May

The city of Quảng Trị was captured by the PAVN, the only provincial capital to fall to them during the Easter Offensive.[19]:2

The preceding week saw South Vietnamese casualties, especially near Quảng Trị, reach their highest level of the entire Vietnam War. The ARVN 3rd and 22nd Divisions had disintegrated.[12]:308

- 2 May

In the first combat kill using the TOW missile the U.S. 1st Combat Aerial TOW Team destroyed an American-made M41 operated by the PAVN near An Lộc.[38]

- 3 May

Lieutenant General Ngô Quang Trưởng assumed command of I Corps replacing the ineffectual General Hoàng Xuân Lãm.

- 4 May

The Paris Peace Talks were suspended indefinitely after the United States and South Vietnam pulled out because of "a lack of progress".[39]

- 6 May

United Press International photographer David Hume Kennerly is awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography for his photos taken in Cambodia and South Vietnam.[40]

- 8 May

Nixon withdrew his demand for a withdrawal of all North Vietnamese forces from South Vietnam as a precondition for a peace agreement. Nixon proposed that all US POWs be released and an internationally supervised cease fire take place. The U.S. would cease bombing and withdraw from South Vietnam within six months after those conditions were met.[41]

Nixon also announced Operation Pocket Money, the mining of Haiphong and other North Vietnamese harbors, calculating correcting that he could take such a step without endangering the U.S.'s improving relationships with China and the Soviet Union.[19]:18 Nixon's action inspired an outbreak of anti-Vietnam War protests around the U.S. with 1,800 arrests of protesters reported.[12]:320

Rear Admiral Rembrandt C. Robinson and two others were killed when their helicopter crashed while landing on USS Providence in the Gulf of Tonkin. He was the only U.S. Navy Flag officer killed in the war.[42]

- 9 May

The PAVN 203rd Tank Regiment attacked Ben Het Camp. ARVN Rangers destroyed the first three PT-76 tanks with BGM-71 TOW missiles, thereby breaking up the attack.[34]:215–217 The Rangers spent the rest of the day stabilising the perimeter ultimately destroying 11 tanks and killing over 100 PAVN.[43]

- 10 May

Lieutenant Duke Cunningham and Lieutenant William P. Driscoll of VF-96 become the only U.S. Navy aces of the war scoring their third, fourth and fifth kills of MiG-17s in a single mission. Their F-4J was then hit by a SAM-2 missile and they ejected successfully over the Gulf of Tonkin and were rescued.[44]

U.S. aircraft achieve their highest number of aerial kills of the war, downing 11 VPAF jets (seven MiG-17s and four MiG-21s)[44]

A U.S. Army CH-47A crashed near Saigon killing all 34 onboard.[45]

- 11 May

USAF First Lieutenant Michael Blassie of the 8th Special Operations Squadron was killed when his A-37B Dragonfly was shot down near An Lộc. His remains and some personal effects were recovered from the crash site by the ARVN five months later and turned over to the U.S. military. The remains were later reclassified as unknown and on 17 May 1984 his remains were designated as the Vietnam Unknown service member. On 28 May 1984 his remains were entombed at Arlington National Cemetery. The remains were exhumed on 14 May 1988 and identified as Blassie through DNA testing. Later in 1988 he was reburied at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.[46]

- 12 May

China condemned the mining of North Vietnamese ports and pledged ongoing support for North Vietnam.[47]:251

- 13 May

The first successful combat use of the laser-guided bomb was accomplished when the Thanh Hóa Bridge was destroyed in North Vietnam, "accomplishing in a single mission what seven years of nonprecision bombing had failed to do". The U.S. had first bombed the 540-foot-long (160 m) concrete and steel structure in 1965.[48]

- 14 May – 9 June

In one of the largest and most intense battles of the Easter Offensive, PAVN forces assaulted the city of Kontum and the nearby South Vietnamese base in the Battle of Kontum. Intensive U.S. airstrikes helped the ARVN fend off the PAVN and retain control of the city and nearby area although fighting in the area would continue.[49]

- 17 May

Operation Enhance began with the objective of replacing material and equipment expended or lost by South Vietnam during the Eastern Offensive. From May to October under Operation Enhance, the U.S. provided the South Vietnamese armed forces with artillery and anti-tank weapons, 69 helicopters, 55 jet fighters, 100 other aircraft and 7 patrol boats.[19]:511

- 22-9 May

Nixon began a state visit to the Soviet Union. The visit was part of his strategy to improve relations with both the Soviet Union and China in order to pressure North Vietnam to accept peace on terms acceptable to the United States.[50]

June

- 2 June

USAF Major Roger Locher, whose F-4D had been shot down on 10 May, was finally rescued after 23 days behind enemy lines. He was 60 miles (97 km) northwest of Hanoi and within 5 miles (8.0 km) of the heavily defended Yên Bái Air Base. His time behind enemy lines and successful rescue was a record for the war and was the farthest penetration of an American search and rescue operation into North Vietnam.[51]

- 3–12 June

Operation Thunderhead was a secret combat mission conducted by U.S. Navy SEAL Team One and Underwater Demolition Team (UDT)-11 in 1972. The mission was conducted off the coast of North Vietnam to rescue two U.S. airmen said to be escaping from a prisoner of war prison in Hanoi.[52]

- 4 June

The first presidential election held in the Khmer Republic resulted in a victory for the incumbent, Lon Nol, although counting within the capital Phnom Penh showed a majority for challenger In Tam. Lon Nol ordered the FANK to collect and count the poll results from the countryside, where In Tam had had greater support, and was soon declared the winner.[53]

- 5 June

An Air America C-46 crashed on approach to Pleiku Air Base killing all 32 onboard.[54]

- 8 June

A South Vietnamese village outside of Trảng Bàng District was bombed with napalm in an errant air strike by the RVNAF. Nick Ut took a photograph that became an iconic symbol of the horrors of war. The wirephoto, published on the front pages of newspapers that evening and the next morning showed children crying in pain from their burns, including a 9-year-old girl, Phan Thị Kim Phúc, who had torn her clothes off after catching fire. The image would win a Pulitzer Prize. [55][56]

- 9 June

John Paul Vann died in a helicopter crash in South Vietnam. Vann, a retired U.S. army Colonel and head of CORDS for the Central Highlands, had directed the defense of Kontum. During his years in Vietnam Vann had acquired much influence and fame and his funeral in Washington was attended by a who's who of U.S. civilian and military leaders.[57]

- 15 June

Cathay Pacific Flight 700Z, operated by a Convair 880 (VR-HFZ) from Bangkok to Hong Kong, disintegrated and crashed while the aircraft was flying at 29,000 feet (8,800 m) over Pleiku after a bomb exploded in a suitcase placed under a seat in the cabin, killing all 81 people on board.[58]

- 15 June - 19 October

Operation Black Lion was an RLA counter-offensive against a PAVN offensive at Khong Sedone. The RLA succeeded in capturing Salavan, but failed to capture Paksan.[14]:349–52

- 18 June

In order to reestablish Soviet supply lines to North Vietnam, China agreed that Soviet bloc ships could unload supplies at Chinese ports which would then be moved by rail into North Vietnam.[47]:254

- 20 June

Responding to a U.S. request for a resumption of secret negotiations, North Vietnam. responded that "clothed by its goodwill, [it] agrees to private meetings." The meetings between Kissinger and Le Duc Tho would begin on 19 July.[59]:8

- 21 June - 21 September 1973

United States Marine Corps aircraft begin operating from Royal Thai Air Base Nam Phong hitting targets in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.[60]

- 28 June – 16 September

The Second Battle of Quảng Trị (Vietnamese: Thành cổ Quảng Trị) began on June 28 and lasted 81 days until September 16, 1972, when the ARVN defeated the PAVN and recaptured most of the province.

- 29 June

The 196th Infantry Brigade departs South Vietnam becoming the last U.S. combat brigade to leave.[60]:286

- 30 June

General Frederick C. Weyand assumes command of MACV from General Abrams who is promoted to Chief of Staff of the United States Army.

July

- 9 July

Brigadier General Richard J. Tallman dies of wounds from PAVN artillery fire in the Battle of An Lộc. He was the last U.S. general officer to be killed in action during the war.[61]

- 11 July

A USMC CH-53D was hit by an SA-7 and crashed near Quảng Trị, killing 3 crewmen and 45 South Vietnamese Marines.[62]

- 12 July

Correspondent Alexander D. Shimkin was killed in a PAVN ambush in Quảng Trị Province. He had earlier raised concerns about potential indiscriminate fire during Operation Speedy Express.[63]

- 15 July

Actress Jane Fonda posed for photographs at a North Vietnamese anti-aircraft gun near Hanoi. Pictures of the actress ran worldwide the next day and earned her the nickname "Hanoi Jane".[64]

- 17 July

The U.S. destroyer USS Warrington was damaged beyond repair by two underwater explosions while operating in the Gulf of Tonkin. The blasts were believed to have been caused by American naval mines that had washed away after having been laid in North Vietnam's ports. The Warrington was towed to Subic Bay Naval Base and decommissioned.[65]

August

- 5–11 August

Task Force Gimlet, Delta Company, 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry undertook the last patrol by U.S. troops in the war to seek out PAVN/VC forces firiing rockets at the city of Da Nang. Two U.S. soldiers were wounded by booby traps. The unit was relieved by ARVN soldiers. Task Force Gimlet departed South Vietnam on 11 August.[28]:544–5

- 6 August - 25 October

Operation Phou Phiang II was an RLA operation to relieve the PAVN siege of Long Tieng. Five columns of RLA/Thai forces attacked PAVN forces but all were defeated despite intensive U.S. air support.[14]:343–8

- 8-22 August

The ARVN 18th Division recapture Quần Lợi Base Camp from the PAVN, using TOW missiles and M-202 rockets to destroy the base's concrete bunkers.[66]

- 12 August

W. Averell Harriman and Cyrus Vance, the two original U.S. negotiators at the Paris Peace Talks, said in a press conference that President Nixon had missed an opportunity in 1969 to end the Vietnam War, at a time when the North Vietnamese had withdrawn most of its combat troops from South Vietnam's northernmost provinces.[67]

C-130E Hercules #62-1853 of the 776th Tactical Airlift Squadron was shot down on takeoff from Sóc Trăng Airfield, killing 30 of 44 passengers and crew on board.[68]

- 13 August

Former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark returned from North Vietnam, where he had traveled as a private individual as part of a factfinding group. Clark said that he had confirmed that the United States was bombing hospitals and dikes, and that he had been told that American prisoners "will be released immediately when we stop this senseless, murderous bombing and end the war and get out, get home, and get to the business of building the peace and giving happiness to little children around the world".[69]

- 28 August

USAF Captain R. Stephen Ritchie became the first USAF ace of the war after downing his fifth VPAF MiG-21 in combat.[70]

- 29 August

President Nixon announced that 12,000 more U.S. soldiers would be withdrawn from South Vietnam over a three-month period, with only 27,000 remaining by 1 December.[71]

- 31 August

U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Ellsworth Bunker said to President Nixon that the South Vietnamese "fear they are not yet well enough organized to compete politically with such a tough, disciplined organization", e.g. North Vietnam.[59]:46

September

- 1 September

Admiral Noel Gayler becomes Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC) replacing Admiral John S. McCain Jr..

- 3 September

The elections for the Khmer Republic's 126-member National Assembly took place. Because of a presidential decree designed to give President Lon Nol's Social Republican Party an advantage, the other parties withdrew from participating. The Socio-Republicans won all 126 seats on what was claimed to be a 78% turnout.[72]

- 9 September

USAF Captain Charles B. DeBellevue became the last and highest scoring U.S. ace of the war with his fifth and sixth MiG kills.[73]

- 13 September

South Vietnamese Marines recaptured Quảng Trị from the PAVN. Quảng Trị had been the only provincial capital to fall to the North Vietnamese in the Easter Offensive.[19]:2

- 14 September

North Vietnamese negotiators in Paris hinted for the first time that they could accept a peace agreement with the United States that did not require the ouster of South Vietnamese President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu.[59]:10

- 17 September

In the first release of prisoners of war since 1969, North Vietnam released three American prisoners, Navy Lieutenants Norris Charles and Markham Gartley and Air Force Major Edward Elias were provided civilian clothes and then allowed to stay in Hanoi with an American welcoming team.[74]

- 26 September

North Vietnamese negotiators in Paris proposed that a "Provisional Government of National Concord" be formed in South Vietnam to organize elections leading to the union of South and North Vietnam.[59]:10

October

- 1 October

An explosion on board the USS Newport News operating off the coast of South Vietnam killed 19 sailors and injured ten others.[75]

- 8 October

In Paris, Le Duc Tho gave Kissinger documents outlining the North Vietnamese proposal for a peace agreement in Vietnam. The proposal dropped demands for the ouster of President Thiệu and called for the withdrawal of all American troops, the release of all American prisoners of war and a cease fire "in place" which would allow PAVN soldiers in South Vietnam to remain there. A tentative text was agreed upon by both sides.[59]:11–3

- 12 October

Kissinger met with Nixon in Washington to explain the draft peace agreement with North Vietnam. Nixon approved the agreement subject to the agreement of President Thiệu.[41]

- 18 October - 22 February 1973

Operation Black Lion III was an RLA offensive to capture Salavan and Paksan. The RLA were initially successful in capturing both cities but were ejected from Paksan by the PAVN in February.[14]:352–3

- 20 October

Operation Enhance Plus began with the objective of providing additional military equipment and support to South Vietnam. Over the next two months the U.S. gave South Vietnam 234 jet fighter planes, 32 transport planes, 277 helicopters, 72 tanks, 117 armored personnel carriers, artillery and 1,726 trucks. The cost of the equipment was more than $750 million ($5.7 billion in 2015 dollars). Moreover, most of the U.S. supplied equipment of two departing South Korean divisions (approximately 38,000 men) was also given to South Vietnam. In addition, the U.S. transferred title of its military bases and all the equipment on the bases to South Vietnam.[76]

- 22 October

After meeting with Kissinger and despite a letter of support from Nixon, President Thiệu said he would never sign the draft peace agreement with North Vietnam. He demanded that all PAVN soldiers be required to leave South Vietnam.[41]

Kissinger in Saigon cabled Nixon in Washington, "While we have a moral case for bombing North Vietnam when it does not accept our proposals, it seems to be really stretching the point to bomb North Vietnam when it has accepted our proposals and South Vietnam has not."[77]:613

- 23 October

The United States halted bombing of North Vietnam above the 20th parallel, bringing to a close Operation Linebacker after nearly six months.

- 25 October

North Vietnam broadcast publicly the terms of the draft peace agreement and accused the United States of negotiating in bad faith.[41]

- 26 October

In Washington, despite the opposition of South Vietnam to the draft peace agreement and the charges by North Vietnam that the U.S. was negotiating in bad faith, Kissinger declared "peace was at hand" in Vietnam.[41]

- 28 October - 22 February 1973

Campaign 972 was a PAVN offensive that effectively succeeded in cutting Laos in two. The operation ended with the ceasefire pursuant to the Vientiane Treaty ending the Laotian Civil War.[14]:394–5

- 31 October

One of the final American special forces operations of the war takes place in an intelligence-gathering mission near Cửa Việt Naval Base, Navy SEAL petty officer Michael E. Thornton saves the life of his commanding officer, Lieutenant Thomas R. Norris; he would later be awarded the Medal of Honor, the latest action in the war for which it was awarded. There were only a dozen Navy SEALs still in Vietnam at the time of the mission.

November

- 7 November

Nixon won reelection with 60.7 percent of the vote.[77]:611

- 14 November

In an attempt to overcome President Thiệu's objection to the draft peace agreement, Nixon wrote him that "You have my absolute assurance that if Hanoi fails to abide by the terms of this agreement, it is my intention to take swift and severe retaliatory action."

- 20 November

Kissinger returned to Paris to meet with Le Duc Tho. Tho accused Kissinger of deception. Kissinger introduced Thiệu's objections to the draft peace agreement. Both North Vietnam and South Vietnam were intransigent, the North Vietnamese demanding the agreement be signed as agreed with the United States, South Vietnam demanding changes.[77]:612–3

- 22 November

The first B-52 to be downed by enemy fire in the war was hit by a SAM while on a raid over Vinh. The crew was forced to abandon the damaged aircraft over Thailand.[78]

- 25 November

Anticipating that the peace agreement would require release of all political prisoners, the government of South Vietnam began charging people detained for political reasons with petty crimes, thus ensuring their continued incarceration. Amnesty International estimated that South Vietnam had imprisoned 200,000 people for political reasons, and would release only 5,000 after the peace agreement came into effect.[59]:48

December

- 4 December

Kissinger returned to Paris for further meetings with Le Duc Tho. The negotiations went nowhere and Kissinger returned to Washington on 13 December.[79]

- 12 December

President Thiệu announced that he still opposed the "false peace" in the draft peace agreement.[19]:2

- 14 December

Nixon met Kissinger and Presidential military aide General Alexander Haig in Washington and the three of them agreed on an intensified bombing campaign against North Vietnam to, in the words of Haig, "strike hard ... and keep on striking until the enemy's will was broken." The weapon of choice would be the B-52, which had never been used before to strike targets in the vicinity of Hanoi and the city of Haiphong.[33]:143–4

All members of the New Zealand armed forces were withdrawn from South Vietnam.[80]

- 16 December

At a press conference, speaking of the negotiations with North Vietnam Kissinger said that "the United States will not be blackmailed into an agreement." Kissinger also warned South Vietnam that "no other party will have a veto over our actions."[33]:145

- 17 December

American warplanes dropped mines off the coast of North Vietnam to prevent ship travel to and from the country.[33]:145

- 18 December

Operation Linebacker II began. Better known as the "Christmas bombings", 129 B-52s and smaller tactical aircraft struck at targets in North Vietnam, including around the city of Hanoi. North Vietnam shot down three B-52s.[33]:145–6

- 19 December

Military adviser Alexander Haig met with Thiệu in Saigon to deliver a letter from Nixon. Nixon said it was his "irrevocable intention" to achieve a peace agreement with North Vietnam, preferably with the cooperation of South Vietnam, "but, if necessary, alone." He pledged continue military support to South Vietnam if Hanoi violated the agreement. Haig told Thiệu, "Under no circumstances will President Nixon accept a veto from Saigon in regard to a peace agreement."[33]:148

North Vietnamese coastal artillery fire hits the USS Goldsborough killing three crewmen.[81]

- 20 December

North Vietnamese negotiator Xuan Thuy responded to Kissinger's remarks of 16 December. He criticized the U.S. for attempting to introduce changes to the draft peace agreement of October.[33]:146

Thiệu kept Haig waiting for five hours before seeing him. He attempted to persuade Haig that the U.S. should require the withdrawal of all PAVN soldiers from South Vietnam in any peace agreement. Haig suggested to Nixon that if a peace agreement was not reached the U.S. could consider a unilateral disengagement from South Vietnam in exchange for the return of American POWs by North Vietnam.[33]:148–9

North Vietnam shot down six B-52s, but depleted their supply of SAMs.[33]:147

- 21 December

Fearing additional losses, the U.S. deployed only 30 B-52s to bomb mostly around Hanoi and Haiphong. Nevertheless, four B-52s were hit by missiles. B-52 crew members complained that the flight patterns assigned to them increased their risk. Flight patterns were changed for subsequent days.[33]:149–50

- 22 December

Nixon offered to suspend the U.S. bombing north of the 20th parallel on 31 December if Hanoi agreed to a 3 January meeting in Paris.[33]:149

The Bach Mai Hospital in Hanoi was struck by seven bombs killing 18 people. The U.S. aircraft were targeting the adjacent Bach Mai Airfield, the VPAF's air defense command and control center.[82]

- 23 December

Opposition to the bombing was extensive among American politicians. In the Senate 45 Senators responding to a poll opposed the bombing as compared to 19 who supported it.[33]:153

- 26 December

After a Christmas truce, the U.S. conducted the largest B-52 raid of the war utilizing 120 B-52s. The U.S. lost 2 airplanes. 215 civilians were killed by bombs dropped on a heavily populated area of Hanoi. North Vietnam proposed a resumption of peace talks on January 8.[33]:150

- 29 December

The last bombs of Operation Linebacker II fell near Hanoi, although the U.S. continued light bombing south of the 20th parallel. Of 200 B-52s engaged in the operation, the U.S. said that 15 were shot down as well as 11 other aircraft, while Hanoi claimed that 34 B-52s had been shot down. 61 B-52 crewmen were killed, captured, or missing. Prior to Linebacker II, during seven years of bombing, only one B-52 had been shot down. Destruction of North Vietnam's military and industrial capacity was substantial. North Vietnam said that 1,623 civilians had been killed in Hanoi and Haiphong although most civilians had been evacuated from the cities before the bombing.[33]:150–3[19]:55

Due to the Operation Linebacker II bombings, 80 percent of North Vietnam's electrical power production capability had been eliminated.

Nixon warned North Vietnam that the bombing would resume if the peace talks collapsed again. North Vietnam declared victory and claimed that heavy losses of American aircraft was the motive behind the bombing halt. General Maxwell Taylor, former Ambassador to South Vietnam, said terminating America's commitment to South Vietnam even without a peace agreement should be considered by the President.[33]:153

- 31 December

U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam numbered 24,200.[83]

- 31 December - 5 February 1973

Operation Maharat II was an RLA offensive to seize the intersection of Routes 7 and 13 from the Pathet Lao. The Pathet Lao withdrew in the face of overwhelming RLA forces.[14]:389–90

Year in numbers

| Armed Force | Strength | KIA | Reference | Military costs - 1972 | Military costs in 2021 US$ | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,048,000 | 39,587 | ||||||

| 24,000 | 641 | [1] | |||||

| 36,790 | 380[84] | [85] | |||||

| 40 | |||||||

| 50 | |||||||

| 50 | |||||||

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vietnam War in 1972. |

- "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. United States Government. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Clarke, Jeffrey (1988). United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965-1973. Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 978-1518612619.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Lewy, Guenter, (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 147

- Deac, Wilfed P. (1996), "Losing Ground to the Khmer Rouge", Vietnam Magazine, Dec 1996, http://www.historynet.com/losing-ground-to-the-khmer-rouge.htm, accessed 9 Jun 2015

- (FRUS) Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976, Volume VIII, Vietnam, January–October 1972, Document 1, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v08/d1#fn3, accessed 8 Jun 2015

- "Nixon Pulls 70,000 More GIs Out of War". Oakland Tribune. 13 January 1972. p. 1.

- Summers, Harry (1999). the Vietnam War Almanac. Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0891416920.

- "Address to the Nation on Plan for Peace in Vietnam", Miller Center. http://millercenter.org/president/nixon/speeches/speech-3879 Archived 2015-03-17 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 8 Jun 2015

- Bob Thompson (27 July 1997). "Richard Nixon and the Oobie-Doobie Girl". The Washington Post.

- "North Vietnam presents 9 Point Peace Proposal," http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/north-vietnam-presents-nine-point-peace-proposal, accessed 8 Jun 2015

- FRUS, document 15, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v08/d15, accessed 8 June 2015

- Bowman, John (1985). The World Almanac of the Vietnam War. Pharos Books. ISBN 978-0886872724.

- Tucker, Spencer, C. (1998), The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, Vol. 1, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 141

- Conboy, Kenneth; Morrison, James (1996). Shadow War: The CIA's Secret War in Laos. Paladin Press. ISBN 0-87364-825-0.

- "400 Bombing Runs Hit Reds". Oakland Tribune. 10 February 1972. p. 1.

- FRUS, document 21, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v08/d21, accessed 10 Jun 2015

- FRUS, document 22, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v08/d22, accessed 10 Jun 2015

- Butterfield, p. 300

- Isaacs, Arnold (1983). Without Honor: Defeat in South Vietnam and Cambodia. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801861079.

- "Reds Walk Out of Paris Talk". Oakland Tribune. 24 February 1972. p. 1.

- Daugherty, Leo (2012), The Vietnam War Day by Day, New York: Chartwell Books, p. 181

- John T. Correll (1 November 2006). "Lavelle". Air Force Magazine.

- Ngo, Quang Truong (1980). The Easter Offensive of 1972 (PDF). U.S. Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "The History Place--Vietnam War 1969-1972", http://www.historyplace.com/unitedstates/vietnam/index-1969.html, accessed 16 Jun 2015

- Clark, p. 481

- Kutler, Stanley I. (1996), Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, pp. 185–186

- Stoffey, Robert; Holloway, James. Fighting to Leave: The Final Years of America's War in Vietnam, 1972-1973. Zenith Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-760333106.

- Andrade, Dale (1994). Trial by Fire: The 1972 Easter Offensive, America's Last Vietnam Battle. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0781802864.

- Prados, John (1995). The Hidden History of the Vietnam War. Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1566630795.

- "United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam 1972-1973 Command History Volume 1" (PDF). United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. 15 July 1973. p. 44. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "War Powers Limits Voted in Senate". Oakland Tribune. 13 April 1972. p. 1.

- Willbanks, James H. (1993), Thiet Giap! The Battle of An Loc April 1972,Combat Studies Institute, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, p. 13 -25-32

- Asselin, Pierre (2002). A Bitter Peace: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807854174.

- Starry, Donn (1978). Mounted Combat In Vietnam Vietnam Studies. Department of the Army. ISBN 978-1780392462.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Melson, Charles (1991). U.S. Marines In Vietnam: The War That Would Not End, 1971–1973. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. ISBN 978-1482384055.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Webb, William J. and Poole, Walter S. (2007), The Joint Chiefs of State and the War in Vietnam, 1971-1973, Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, p. 214. http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/history/vn71_73.pdf%5B%5D, accessed 17 Dec 2015

- "United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam 1972-1973 Command History Annex B" (PDF). United States Military Assistance Command, Vietnam. 15 July 1973. p. B-28. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - McKenna, Thomas (2011). Kontum: The Battle to Save South Vietnam. Battles and Campaigns. University Press of Kentucky. p. 143. ISBN 978-0813165820.

- "U.S., Saigon Call Halt to Paris Talks". Oakland Tribune. 4 May 1972. p. 1.

- "Dave Kennerly of United Press International". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "Memoirs v Tapes: President Nixon and the December Bombings", http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/exhibits/decbomb/chapter-ii.html Archived 2018-07-12 at the Wayback Machine., accessed 23 Jun 2015

- Robinson, John. "Pounding the Do Son Peninsula" (PDF). Naval Institute Proceedings. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- "U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Command History 1972, Annex K. Kontum, 1973. MACV" (PDF). p. K-14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Marolda, Edward (1996). By Sea, Air, and Land: An Illustrated History of the U. S. Navy and the War in Southeast Asia. DIANE Publishing. p. 393. ISBN 9780788132506.

- "Boeing CH-47A Chinook 64-13157". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- "Michael Blassie unknown no more". National Institutes of Heath. 3 May 2006. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Nguyen, Lien-Hang (2012). Hanoi's War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3551-7.

- Gillespie, Paul (2006). Weapons of choice: the development of precision guided munitions. University of Alabama Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0817315320.

- Fulghum, David and Maitland, Terrence (1984), South Vietnam on Trial, Boston: Boston Publishing Company, pp. 156–159

- Nixon, Richard (1985). No More Vietnams. Arbor House Publishing Company. pp. 105–6. ISBN 978-0-87795-668-6.

- Frisbee, John L. (March 1992). "Valor: A Good Thought to Sleep On". 75 (3). AirforceMagazine.com. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dale Eisman (26 February 2008). "Navy honors SEAL killed in secret mission in Vietnam". The Virginian-Pilot.

- Soonthornpoct, Punee (2005). From Freedom to Hell: A History of Foreign Intervention in Cambodian Politics and Wars. Vantage Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0533150830.

- "Aircraft accident Curtiss C-46A-45-CU Commando". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- "South Vietnamese Drop Napalm on Own Troops". New York Times. 9 June 1972. p. 1.

- Chong, Denise (2001). The Girl in the Picture: The Story of Kim Phuc, the Photograph, and the Vietnam War. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140280210.

- Sheehan, Neil (1988), A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam, New York: Vintage Books, pp. 4–21

- "Criminal Occurrence description – Convair CV-880-22M-21 VR-HFZ". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Lipsman, Samuel; Weiss, Stephen (1985). The Vietnam Experience: The False Peace, 1972-1974. Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0939526154.

- Dunham, George R (1990). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Bitter End, 1973–1975 (Marine Corps Vietnam Operational Historical Series). History and Museums Division Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 23-4. ISBN 9780160264559.

- Willbanks, James (2005). The Battle of An Loc. Indiana University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780253344816.

- "ASN Wikibase Occurrence #148204". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- Chad Huntley (17 July 1972). "Newspaperman believes service training kept him from being killed". The Star-News (Marine Edition). United Press International. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "The List: Top 10 Jane Fonda mistakes". Washington Times. 23 December 2012. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "2 Underwater Blasts Batter U.S. Destroyer in Tonkin Gulf". Bridgeport Telegram. 18 July 1972. p. 1.

- Lam, Quang Thi (2009). Hell in An Loc: The 1972 Easter Invasion and the Battle that Saved South Vietnam. University of North Texas Press. pp. 198–201. ISBN 9781574412765.

- "Nixon Ignored Peace Bid, Paris Team Says". Oakland Tribune. 13 August 1972. p. 1.

- "Lockheed C-130 E Hercules Soc Trang". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- "Clark Gives Hanoi Peace Plan". El Paso Herald-Post. 14 August 1972. p. 1.

- Handleman, Philip (2003). Combat in the Sky: The Art of Air Warfare. MBI Publishing. p. 134. ISBN 978-0760314685.

- "Nixon Pulls 12,000 More GIs From War". Oakland Tribune. 29 August 1972. p. 1.

- Peou, Sorpong (2000). Intervention & Change in Cambodia: Towards Democracy?. St. Martin's Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0312227173.

- Futrell, Frank (2002). United States Air Force in Southeast Asia 1965–1973: Aces and Aerial Victories. Air University, Headquarters USAF. pp. 93–105. ISBN 978-1508789918.

- "3 Released POWs Await Trip Home". Oakland Tribune. 18 September 1972. p. 1.

- "19 Killed in Blast Aboard U.S. Cruiser". Oakland Tribune. 1 October 1972. p. 1.

- Jacobs, pp. 48–49, 511

- Langguth, A.J. (2000). Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975. Touchstone Books. ISBN 978-0684812021.

- "Reds Down First B52, Crew Saved". Oakland Tribune. 22 November 1972. p. 1.

- "Memoirs v. Tapes: President Nixon and the December Bombings" http://www.nixonlibrary.gov/exhibits/decbomb/chapter-iv.html#title Archived 2015-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 25 Jun 2015

- Jessup, John (1998). An encyclopedic dictionary of conflict and conflict resolution, 1945-1996 (1998 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 523. ISBN 0-313-28112-2.

- Silverstone, Paul (2011). The Navy of the Nuclear Age, 1947–2007. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 9781135864668.

- "Linebacker and the Law of War". Air University Review. United States Air Force. 37: 25. 1985.

- "Vietnam War Timeline: 1971-1972," http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1971.aspx, accessed 7 Jun 2015

- Benjamin Engel (Summer 2016). "Viewing Seoul from Saigon: Withdrawal from the Vietnam War and the Yushin Regime". The Journal of Northeast Asian History. 13 (1): 98.

- Leepson, Marc; Hannaford, Helen (1999). Webster's New World Dictionary of the Vietnam War. Simon & Schuster. p. 209. ISBN 0028627466.