Battle of Khe Sanh

The Battle of Khe Sanh (21 January – 9 July 1968) was conducted in the Khe Sanh area of northwestern Quảng Trị Province, Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), during the Vietnam War. The main US forces defending Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB) were two regiments of the United States Marine Corps supported by elements from the United States Army and the United States Air Force (USAF), as well as a small number of Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops. These were pitted against two to three divisional-size elements of the North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN).

| Battle of Khe Sanh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||

A burning fuel dump after a mortar attack at Khe Sanh | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

(Theater) (3rd Marine Div) (Local) |

Võ Nguyên Giáp (Theater) Tran Quy Hai (Local, Military) Lê Quang Đạo (Local, Political) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

~45,000 in total[11] |

Siege at Khe Sanh: ~17,200 (304th and 308th Division)[12] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total (21 January – 9 July): 12,000+ casualties(2,800–3,500 killed, 9,000+ wounded, 7 missing, 250+ captured)[13][Note 1] |

Unknown (1,602 bodies were counted, US official public estimated 10,000–15,000 KIA,[16][17] but MACV's secret report estimated 5,550 KIA[1]) 1,436 wounded (before mid-March)[18] 2,469 KIA (from 20 January until 20 July 1968).[1] | ||||||

The US command in Saigon initially believed that combat operations around KSCB during 1967 were part of a series of minor PAVN offensives in the border regions. That appraisal was later altered when the PAVN was found to be moving major forces into the area. In response, US forces were built up before the PAVN isolated the Marine base. Once the base came under siege, a series of actions was fought over a period of five months. During this time, KSCB and the hilltop outposts around it were subjected to constant PAVN artillery, mortar, and rocket attacks, and several infantry assaults. To support the Marine base, a massive aerial bombardment campaign (Operation Niagara) was launched by the USAF. Over 100,000 tons of bombs were dropped by US aircraft and over 158,000 artillery rounds were fired in defense of the base. Throughout the campaign, US forces used the latest technology to locate PAVN forces for targeting. Additionally, the logistical effort required to support the base once it was isolated demanded the implementation of other tactical innovations to keep the Marines supplied.

In March 1968, an overland relief expedition (Operation Pegasus) was launched by a combined Marine–Army/ARVN task force that eventually broke through to the Marines at Khe Sanh. American commanders considered the defense of Khe Sanh a success, but shortly after the siege was lifted, the decision was made to dismantle the base rather than risk similar battles in the future. On 19 June 1968, the evacuation and destruction of KSCB began. Amid heavy shelling, the Marines attempted to salvage what they could before destroying what remained as they were evacuated. Minor attacks continued before the base was officially closed on 5 July. Marines remained around Hill 689, though, and fighting in the vicinity continued until 11 July until they were finally withdrawn, bringing the battle to a close.

In the aftermath, the North Vietnamese proclaimed a victory at Khe Sanh, while US forces claimed that they had withdrawn, as the base was no longer required. Historians have observed that the Battle of Khe Sanh may have distracted American and South Vietnamese attention from the buildup of Viet Cong (VC) forces in the south before the early 1968 Tet Offensive. Nevertheless, the US commander during the battle, General William Westmoreland, maintained that the true intention of Tet was to distract forces from Khe Sanh.

Prelude

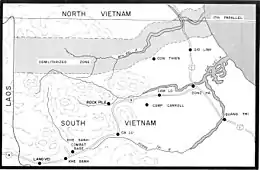

The village of Khe Sanh was the seat of government of Hương Hoa district, an area of Bru Montagnard villages and coffee plantations, situated about 7 miles (11 km) from the Laotian frontier on Route 9, the northernmost transverse road in South Vietnam. The badly deteriorated Route 9 ran from the coastal region through the western highlands, and then crossed the border into Laos. The origin of the combat base lay in the construction by US Army Special Forces of an airfield in August 1962 outside the village at an old French fort.[19] The camp then became a Special Forces outpost of the Civilian Irregular Defense Groups, whose purpose was to keep watch on PAVN infiltration along the border and to protect the local population.[20][Note 2]

James Marino wrote that in 1964, General Westmoreland, the US commander in Vietnam, had determined, "Khe Sanh could serve as a patrol base blocking enemy infiltration from Laos; a base for ... operations to harass the enemy in Laos; an airstrip for reconnaissance to survey the Ho Chi Minh Trail; a western anchor for the defenses south of the DMZ; and an eventual jumping-off point for ground operations to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail."[21] In November 1964, the Special Forces moved their camp to the Xom Cham Plateau, the future site of Khe Sanh Combat Base.[22]

During the winter of 1964, Khe Sanh became the location of a launch site for the highly classified Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (the site was first established near the village and was later moved to the French fort).[23] From there, reconnaissance teams were launched into Laos to explore and gather intelligence on the PAVN logistical system known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail (also known as "Truong Son Strategic Supply Route" to the North Vietnamese soldiers).[22]

According to Marino, "by 1966, Westmoreland had begun to consider Khe Sanh as part of a larger strategy". With a view to eventually gaining approval for an advance through Laos to interdict the Ho Chi Minh Trail, he determined, "it was absolutely essential to hold the base", and he gave the order for US Marines to take up positions around Khe Sanh. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam subsequently began planning for incursion into Laos, and in October, construction of an airfield at Khe Sanh was completed.[21]

The plateau camp was permanently manned by the US Marines during 1967, when they established an outpost next to the airstrip. This base was to serve as the western anchor of Marine Corps forces, which had tactical responsibility for the five northernmost provinces of South Vietnam known as I Corps.[24][25] The Marines' defensive system stretched below the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) from the coast, along Route 9, to Khe Sanh. During 1966 the regular Special Forces troops had moved off the plateau and built a smaller camp down Route 9 at Lang Vei, about half the distance to the Laotian border.[26]

Background

Border battles

During the second half of 1967, the North Vietnamese instigated a series of actions in the border regions of South Vietnam. All of these attacks were conducted by regimental-size PAVN/VC units, but unlike the usual hit-and-run tactics used previously, these were sustained and bloody affairs.[27]

In early October, the PAVN had intensified battalion-sized ground probes and sustained artillery fire against Con Thien, a hilltop stronghold in the center of the Marines' defensive line south of the DMZ in northern Quảng Trị Province.[28] Mortar rounds, artillery shells, and 122 mm rockets fell randomly, but incessantly, upon the base. The September bombardments ranged from 100 to 150 rounds per day, with a maximum on 25 September of 1,190 rounds.[29] Westmoreland responded by launching Operation Neutralize, an aerial and naval bombardment campaign designed to break the siege. For seven weeks, American aircraft dropped from 35,000 to 40,000 tons of bombs in nearly 4,000 airstrikes.[30]

On 27 October, a PAVN regiment attacked an Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) battalion at Song Be, capital of Phước Long Province.[30] The PAVN fought for several days, took casualties, and fell back. Two days later, the PAVN 273rd Regiment attacked a Special Forces camp near the border town of Loc Ninh, in Bình Long Province.[30] Troops of the US 1st Infantry Division were able to respond quickly. After a ten-day battle, the attackers were pushed back into Cambodia. At least 852 PAVN soldiers were killed during the action, as opposed to 50 American and South Vietnamese dead.[30]

The heaviest action took place near Dak To, in the central highlands province of Kon Tum. There, the presence of the PAVN 1st Division prompted a 22-day battle that had some of the most intense close-quarters fighting of the entire conflict.[31] American intelligence estimated between 1,200 and 1,600 PAVN troops were killed, while 362 members of the US 4th Infantry Division, the 173rd Airborne Brigade, and ARVN Airborne elements were killed in action. Nonetheless, three of the four battalions of the 4th Infantry and the entire 173rd were rendered combat ineffective during the battle.[32]

American intelligence analysts were quite baffled by this series of enemy actions. For them, no logic was apparent behind the sustained PAVN/VC offensives, other than to inflict casualties on the allied forces. This they accomplished, but the casualties absorbed by the North Vietnamese seemed to negate any direct gains they might have obtained. The border battles did, however, have two significant consequences that were unappreciated at the time: they fixed the attention of the American command on the border regions, and they drew American and ARVN forces away from the coastal lowlands and cities, in preparation for the Tet Offensive.[33]

Hill fights

Things remained quiet in the Khe Sanh area through 1966. Even so, Westmoreland insisted that it not only be occupied by the Marines, but that it also be reinforced.[34] He was vociferously opposed by General Lewis W. Walt, the Marine commander of I Corps. Walt argued heatedly that the real target of the American effort should be the pacification and protection of the population, not chasing the PAVN/VC in the hinterlands.[35] Westmoreland won out, however, and the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment (1/3 Marines) was dispatched to occupy the camp and airstrip on 29 September. By late January 1967, the 1/3 returned to Japan and was relieved by Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines (1/9 Marines). A single company was replacing an entire battalion.[36]

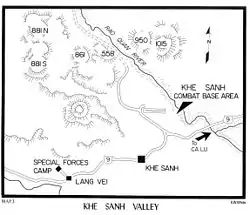

On 24 April 1967, a patrol from Bravo Company became engaged with a PAVN force of unknown size north of Hill 861. This action prematurely triggered a PAVN offensive aimed at taking Khe Sanh. The PAVN forces were in the process of gaining elevated terrain before the launching of the main attack.[37] The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 3rd Marine Regiment, under the command of Colonel John P. Lanigan, reinforced KSCB and were given the task of pushing the PAVN off of Hills 861, 881 North, and 881 South. PAVN forces were driven out of the area around Khe Sanh after suffering 940 casualties. The Marines suffered 155 killed in action and 425 wounded.[38] To prevent PAVN observation of the main base at the airfield (and their possible use as firebases), the hills of the surrounding Khe Sanh Valley had to be continuously occupied and defended by separate Marine elements.[39]

In the wake of the hill fights, a lull in PAVN activity occurred around Khe Sanh. By the end of May, Marine forces were again drawn down from two battalions to one, the 1st Battalion, 26th Marines.[40] Lieutenant General Robert E. Cushman, Jr. relieved Walt as commander of III MAF in June.[41]

On 14 August, Colonel David E. Lownds took over as commander of the 26th Marine Regiment. Sporadic actions were taken in the vicinity during the late summer and early fall, the most serious of which was the ambush of a supply convoy on Route 9. This proved to be the last overland attempt at resupply for Khe Sanh until the following March.[42] During December and early January, numerous sightings of PAVN troops and activities were made in the Khe Sanh area, but the sector remained relatively quiet.[43]

Decisions

A decision then had to be made by the American high command: either commit more of the limited manpower in I Corps to the defense of Khe Sanh or abandon the base.[44][Note 3] Westmoreland regarded this choice as quite simple. In his memoirs, he listed the reasons for a continued effort

Khe Sanh could serve as a patrol base for blocking enemy infiltration from Laos along Route 9; as a base for SOG operations to harass the enemy in Laos; as an airstrip for reconnaissance planes surveying the Ho Chi Minh Trail; as the western anchor for defenses south of the DMZ; and as an eventual jump-off point for ground operations to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[45][Note 4]

Leading Marine officers, however, were not all of the same opinion. Cushman, the new III MAF commander, supported Westmoreland (perhaps wanting to mend Army/Marine relations after the departure of Walt).[48] Other concerns raised included the assertion that the real danger to I Corps was from a direct threat to Quảng Trị City and other urban areas; that a defense would be pointless as a threat to infiltration, since PAVN troops could easily bypass Khe Sanh; that the base was too isolated and that the Marines "had neither the helicopter resources, the troops, nor the logistical bases for such operations". Additionally, Shore argues that the "weather was another critical factor because the poor visibility and low overcasts attendant to the monsoon season made such operations hazardous."[49] Brigadier General Lowell English (assistant commander 3rd Marine Division) complained that the defense of the isolated outpost was ludicrous. "When you're at Khe Sanh, you're not really anywhere. You could lose it and you really haven't lost a damn thing."[50]

As far as Westmoreland was concerned, however, all he needed to know was that the PAVN had massed large numbers of troops for a set-piece battle. Making the prospect even more enticing was that the base was in an unpopulated area where American firepower could be fully employed without civilian casualties. The opportunity to engage and destroy a formerly elusive enemy that was moving toward a fixed position promised a victory of unprecedented proportions.[50]

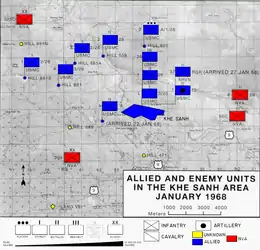

Battle

First skirmishes

In early December 1967, the PAVN appointed Major General Tran Quy Hai as the local commander for the actions around Khe Sanh, with Le Quang Dạo as his political commissar. In the coming days, a campaign headquarters was established around Sap Lit.[51] Two divisions, the 304th and the 325th, were assigned to the operation: the 325th was given responsibility for the area around the north, while the 304th was given responsibility for the southern sector.[52] In attempting to determine PAVN intentions Marine intelligence confirmed that, within a period of just over a week, the 325th Division had moved into the vicinity of the base and two more divisions were within supporting distance. The 324th Division was located in the DMZ area 10–15 miles (16–24 km) north of Khe Sanh while the 320th Division was within easy reinforcing distance to the northeast.[53] They were supported logistically from the nearby Ho Chi Minh Trail. As a result of this intelligence, KSCB was reinforced on 13 December by the 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment. According to the official PAVN history, by December 1967 the North Vietnamese had in place, or within supporting distance: the 304th, 320th, 324th and 325th Infantry Divisions, the independent 270th infantry Regiment; five artillery regiments (the 16th, 45th, 84th, 204th, and 675th); three AAA regiments (the 208th, 214th, and 228th); four tank companies; one engineer regiment plus one independent engineer battalion; one signal battalion; and a number of local force units.[54]

At positions west of Hill 881 South and north of Co Roc Ridge (16.561°N 106.632°E), across the border in Laos, the PAVN established artillery, rocket, and mortar positions from which to launch attacks by fire on the base and to support its ground operations. The PAVN 130 mm and 152 mm artillery pieces, and 122 mm rockets, had a longer range than the Marine artillery support which consisted of 105 mm and 155 mm howitzers. This range overmatch was used by the PAVN to avoid counter-battery fire.[55][56] They were assisted in their emplacement efforts by the continuing bad weather of the winter monsoon.[57]

During the rainy night of 2 January 1968, six men dressed in black uniforms were seen outside the defensive wire of the main base by members of a listening post. After failing to respond to a challenge, they were fired upon and five were killed outright while the sixth, although wounded, escaped.[Note 5] This event prompted Cushman to reinforce Lownds with the rest of the 2nd Battalion, 26th Marines. This marked the first time that all three battalions of the 26th Marine Regiment had operated together in combat since the Battle of Iwo Jima during the Second World War.[59] To cover a defilade near the Rao Quan River, four companies from 2/26 were immediately sent out to occupy Hill 558, with another manning Hill 861A.[60]

On 20 January, La Thanh Ton, a PAVN lieutenant from the 325th Division, defected and laid out the plans for an entire series of PAVN attacks.[61] Hills 881 South, 861, and the main base itself would be simultaneously attacked that same evening. At 00:30 on 21 January, Hill 861 was attacked by about 300 PAVN troops, the Marines, however, were prepared. The PAVN infantry, though bracketed by artillery fire, still managed to penetrate the perimeter of the defenses and were only driven back after severe close-quarters combat.[62]

The main base was then subjected to an intense mortar and rocket barrage. Hundreds of mortar rounds and 122-mm rockets slammed into the base, levelling most of the above-ground structures. One of the first enemy shells set off an explosion in the main ammunition dump. Many of the artillery and mortar rounds stored in the dump were thrown into the air and detonated on impact within the base. Soon after, another shell hit a cache of tear gas, which saturated the entire area.[63] The fighting and shelling on 21 January resulted in 14 Marines killed and 43 wounded.[64] Hours after the bombardment ceased, the base was still in danger. At around 10:00, the fire ignited a large quantity of explosives, rocking the base with another series of detonations.[65]

At the same time as the artillery bombardment at KSCB, an attack was launched against Khe Sanh village, seat of Hướng Hóa District. The village, 3 km south of the base, was defended by 160 local Bru troops, plus 15 American advisers. At dawn on 21 January, it was attacked by a roughly 300-strong PAVN battalion. A platoon from Company D, 1/26 Marines was sent from the base but was withdrawn in the face of the superior PAVN forces. Reinforcements from the ARVN 256th Regional Force (RF) company were dispatched aboard nine UH-1 helicopters of the 282nd Assault Helicopter Company, but they were landed near the abandoned French fort/former FOB-3 which was occupied by the PAVN who killed many of the RF troops and 4 Americans, including Lieutenant colonel Joseph Seymoe the deputy adviser for Quang Tri Province and forcing the remaining helicopters to abandon the mission. On the morning of 22 January Lownds decided to evacuate the remaining forces in the village with most of the Americans evacuated by helicopter while two advisers led the surviving local forces overland to the combat base.[18][66]

To eliminate any threat to their flank, the PAVN attacked Laotian Battalion BV-33, located at Ban Houei Sane, on Route 9 in Laos. The battalion was assaulted on the night of 23 January by three PAVN battalions supported by seven tanks. The Laotians were overrun, and many fled to the Special Forces camp at Lang Vei. The Battle of Ban Houei Sane, not the attack three weeks later at Lang Vei, marked the first time that the PAVN had committed an armored unit to battle.[18]

PAVN artillery fell on the main base for the first time on 21 January. Several rounds also landed on Hill 881.[67] Due to the arrival of the 304th Division, KSCB was further reinforced by the 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment on 22 January. Five days later, the final reinforcements arrived in the form of the 37th ARVN Ranger Battalion, which was deployed more for political than tactical reasons.[68] The Marines and ARVN dug in and hoped that the approaching Tết truce (scheduled for 29–31 January) would provide some respite. On the afternoon of 29 January, however, the 3rd Marine Division notified Khe Sanh that the truce had been cancelled. The Tet Offensive was about to begin.[69][70]

Westmoreland's plan to use nuclear weapons

Nine days before the Tet Offensive broke out, the PAVN opened the battle of Khe Sanh and attacked the US forces just south of the DMZ. Declassified documents show that in response, Westmoreland considered using nuclear weapons. In 1970, the Office of Air Force History published a then "top secret", but now declassified, 106-page report, titled The Air Force in Southeast Asia: Toward a Bombing Halt, 1968. Journalist Richard Ehrlich writes that according to the report, "in late January, General Westmoreland had warned that if the situation near the DMZ and at Khe Sanh worsened drastically, nuclear or chemical weapons might have to be used." The report continues to state, "this prompted Air Force chief of staff, General John McConnell, to press, although unsuccessfully, for JCS (Joint Chiefs of Staff) authority to request Pacific Command to prepare a plan for using low-yield nuclear weapons to prevent a catastrophic loss of the U.S. Marine base."[71]

Nevertheless, ultimately the nuclear option was discounted by military planners. A secret memorandum reported by US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, sent to US President Lyndon B. Johnson on 19 February 1968, was declassified in 2005. It reveals that the nuclear option was discounted because of terrain considerations that were unique to South Vietnam, which would have reduced the effectiveness of tactical nuclear weapons. McNamara wrote: "because of terrain and other conditions peculiar to our operations in South Vietnam, it is inconceivable that the use of nuclear weapons would be recommended there against either Viet Cong or North Vietnamese forces". McNamara's thinking may have also been affected by his aide David Morrisroe (later VP at Cal Tech where McNamara later served as Trustee), whose brother Michael Morrisroe (1960 New York State Chess Champion) was serving at the base.[72]

Operation Niagara

During January, the recently installed electronic sensors of Operation Muscle Shoals (later renamed "Igloo White"), which were undergoing test and evaluation in southeastern Laos, were alerted by a flurry of PAVN activity along the Ho Chi Minh Trail opposite the northwestern corner of South Vietnam. Due to the nature of these activities, and the threat that they posed to KSCB, Westmoreland ordered Operation Niagara I, an intense intelligence collection effort on PAVN activities in the vicinity of the Khe Sanh Valley.[73]

Niagara I was completed during the third week of January, and the next phase, Niagara II, was launched on the 21st,[74] the day of the first PAVN artillery barrage.[67] The Marine Direct Air Support Center (DASC), located at KSCB, was responsible for the coordination of air strikes with artillery fire. An airborne battlefield command and control center aboard a C-130 aircraft, directed incoming strike aircraft to forward air control (FAC) spotter planes, which, in turn directed them to targets either located by themselves or radioed in by ground units.[75] When weather conditions precluded FAC-directed strikes, the bombers were directed to their targets by either a Marine AN/TPQ-10 radar installation at KSCB or by Air Force Combat Skyspot MSQ-77 stations.[76]

Thus began what was described by John Morocco as "the most concentrated application of aerial firepower in the history of warfare".[77] On an average day, 350 tactical fighter-bombers, 60 B-52s, and 30 light observation or reconnaissance aircraft operated in the skies near the base.[78] Westmoreland had already ordered the nascent Igloo White operation to assist in the Marine defense.[73] On 22 January, the first sensor drops took place, and by the end of the month, 316 acoustic and seismic sensors had been dropped in 44 strings.[79] The sensors were implanted by a special naval squadron, Observation Squadron Sixty-Seven (VO-67). The Marines at KSCB credited 40% of intelligence available to their fire-support coordination center to the sensors.[80]

By the end of the battle, USAF assets had flown 9,691 tactical sorties and dropped 14,223 tons of bombs on targets within the Khe Sanh area. Marine Corps aviators had flown 7,098 missions and released 17,015 tons. Naval aircrews, many of whom were redirected from Operation Rolling Thunder strikes against North Vietnam, flew 5,337 sorties and dropped 7,941 tons of ordnance in the area.[81] Westmoreland later wrote, "Washington so feared that some word of it might reach the press that I was told to desist, ironically answering what those consequences could be: a political disaster."[82]

Meanwhile, an interservice political struggle took place in the headquarters at Phu Bai Combat Base, Saigon, and the Pentagon over who should control aviation assets supporting the entire American effort in Southeast Asia.[83] Westmoreland had given his deputy commander for air operations, Air Force General William W. Momyer, the responsibility for coordinating all air assets during the operation to support KSCB. This caused problems for the Marine command, which possessed its own aviation squadrons that operated under their own close air support doctrine. The Marines were extremely reluctant to relinquish authority over their aircraft to an Air Force general.[84] The command and control arrangement then in place in Southeast Asia went against Air Force doctrine, which was predicated on the single air manager concept. One headquarters would allocate and coordinate all air assets, distributing them wherever they were considered most necessary, and then transferring them as the situation required. The Marines, whose aircraft and doctrine were integral to their operations, were under no such centralized control. On 18 January, Westmoreland passed his request for Air Force control up the chain of command to CINCPAC in Honolulu.[85]

Heated debate arose among Westmoreland, Commandant of the Marine Corps Leonard F. Chapman, Jr., and Army Chief of Staff Harold K. Johnson. Johnson backed the Marine position due to his concern over protecting the Army's air assets from Air Force co-option.[86] Westmoreland was so obsessed with the tactical situation that he threatened to resign if his wishes were not obeyed.[87] As a result, on 7 March, for the first time during the Vietnam War, air operations were placed under the control of a single manager.[78] Westmoreland insisted for several months that the entire Tet Offensive was a diversion, including, famously, attacks on downtown Saigon and obsessively affirming that the true objective of the North Vietnamese was Khe Sanh.[88]

Fall of Lang Vei

The Tet Offensive was launched prematurely in some areas on 30 January. On the following night, a massive wave of PAVN/VC attacks swept throughout South Vietnam, everywhere except Khe Sanh. The launching of the largest enemy offensive thus far in the conflict did not shift Westmoreland's focus away from Khe Sanh. A press release prepared on the following day (but never issued), at the height of Tet, showed that he was not about to be distracted. "The enemy is attempting to confuse the issue ... I suspect he is also trying to draw everyone's attention away from the greatest area of threat, the northern part of I Corps. Let me caution everyone not to be confused."[89][90]

Not much activity (with the exception of patrolling) had occurred thus far during the battle for the Special Forces of Detachment A-101 and their four companies of Bru CIDGs stationed at Lang Vei. Then, on the morning of 6 February, the PAVN fired mortars into the Lang Vei compound, wounding eight Camp Strike Force soldiers.[91] At 18:10 hours, the PAVN followed up their morning mortar attack with an artillery strike from 152 mm howitzers, firing 60 rounds into the camp. The strike wounded two more Strike Force soldiers and damaged two bunkers.[91]

The situation changed radically during the early morning hours of 7 February. The Americans had forewarning of PAVN armor in the area from Laotian refugees from camp BV-33. SOG Reconnaissance teams also reported finding tank tracks in the area surrounding Co Roc mountain.[92] Although the PAVN was known to possess two armored regiments, it had not yet fielded an armored unit in South Vietnam, and besides, the Americans considered it impossible for them to get one down to Khe Sanh without it being spotted by aerial reconnaissance.[93]

It still came as a shock to the Special Forces troopers at Lang Vei when 12 tanks attacked their camp. The Soviet-built PT-76 amphibious tanks of the 203rd Armored Regiment churned over the defenses, backed up by an infantry assault by the 7th Battalion, 66th Regiment and the 4th Battalion of the 24th Regiment, both elements of the 304th Division. The ground troops had been specially equipped for the attack with satchel charges, tear gas, and flame throwers. Although the camp's main defenses were overrun in only 13 minutes, the fighting lasted for several hours, during which the Special Forces men and Bru CIDGs managed to knock out at least five of the tanks.[94]

The Marines at Khe Sanh had a plan in place for providing a ground relief force in just such a contingency, but Lownds, fearing a PAVN ambush, refused to implement it. Lownds also rejected a proposal to launch a helicopter extraction of the survivors.[95] During a meeting at Da Nang at 07:00 the next morning, Westmoreland and Cushman accepted Lownds' decision. Army Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Ladd (commander, 5th Special Forces Group), who had just flown in from Khe Sanh, was reportedly, "astounded that the Marines, who prided themselves on leaving no man behind, were willing to write off all of the Green Berets and simply ignore the fall of Lang Vei."[95]

Ladd and the commander of the SOG compound (whose men and camp had been incorporated into the defenses of KSCB) proposed that, if the Marines would provide the helicopters, the SOG reconnaissance men would go in themselves to pick up any survivors.[96] The Marines continued to oppose the operation until Westmoreland actually had to issue an order to Cushman to allow the rescue operation to proceed.[97] The relief effort was not launched until 15:00, and it was successful. Of the 500 CIDG troops at Lang Vei, 200 had been killed or were missing and 75 more were wounded. Of the 24 Americans at the camp, 10 had been killed and 11 wounded.[98][Note 6]

Lownds infuriated the Special Forces personnel even further when the indigenous survivors of Lang Vei, their families, civilian refugees from the area, and Laotian survivors from the camp at Ban Houei Sane arrived at the gate of KSCB. Lownds feared that PAVN infiltrators were mixed up in the crowd of more than 6,000, and lacked sufficient resources to sustain them. Overnight, they were moved to a temporary position a short distance from the perimeter and from there, some of the Laotians were eventually evacuated, although the majority turned around and walked back down Route 9 toward Laos.[100]

The Lao troops were eventually flown back to their homeland, but not before the Laotian regional commander remarked that his army had to "consider the South Vietnamese as enemy because of their conduct."[101] The Bru were excluded from evacuation from the highlands by an order from the ARVN I Corps commander, who ruled that no Bru be allowed to move into the lowlands.[102] Ladd, back on the scene, reported that the Marines stated, "they couldn't trust any gooks in their damn camp."[103] There had been a history of distrust between the Special Forces personnel and the Marines, and General Rathvon M. Tompkins, commander of the 3rd Marine Division, described the Special Forces soldiers as "hopped up ... wretches ... [who] were a law unto themselves."[104] At the end of January, Tompkins had ordered that no Marine patrols proceed more than 500 meters from the Combat Base.[68] Regardless, the SOG reconnaissance teams kept patrolling, providing the only human intelligence available in the battle area. This, however, did not prevent the Marine tanks within the perimeter from training their guns on the SOG camp.[103]

Logistics and supporting fire

Lownds estimated that the logistical requirements of KSCB were 60 tons per day in mid-January and rose to 185 tons per day when all five battalions were in place.[105] The greatest impediments to the delivery of supplies to the base were the closure of Route 9 and the winter monsoon weather. For most of the battle, low-lying clouds and fog enclosed the area from early morning until around noon, and poor visibility severely hampered aerial resupply.[57]

Making matters worse for the defenders, any aircraft that braved the weather and attempted to land was subject to PAVN antiaircraft fire on its way in for a landing. Once the aircraft touched down, it became the target of any number of PAVN artillery or mortar crews. The aircrew then had to contend with antiaircraft fire on the way out. As a result, 65% of all supplies were delivered by paradrops delivered by C-130 aircraft, mostly by the USAF, whose crews had significantly more experience in airdrop tactics than Marine air crews.[106] The most dramatic supply delivery system used at Khe Sanh was the Low Altitude Parachute Extraction System, in which palletized supplies were pulled out of the cargo bay of a low-flying transport aircraft by means of an attached parachute. The pallet slid to a halt on the airstrip while the aircraft never had to actually land.[56] The USAF delivered 14,356 tons of supplies to Khe Sanh by air (8,120 tons by paradrop). 1st Marine Aircraft Wing records claim that the unit delivered 4,661 tons of cargo into KSCB.[107]

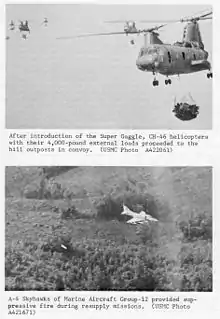

The resupply of the numerous, isolated hill outposts was fraught with the same difficulties and dangers. The fire of PAVN antiaircraft units took its toll of helicopters that made the attempt. The Marines found a solution to the problem in the "Super Gaggle" concept. A group of 12 A-4 Skyhawk fighter-bombers provided flak suppression for massed flights of 12–16 helicopters, which would resupply the hills simultaneously. The adoption of this concept at the end of February was the turning point in the resupply effort. After its adoption, Marine helicopters flew in 465 tons of supplies during February. When the weather later cleared in March, the amount was increased to 40 tons per day.[108]

As more infantry units had been assigned to defend KSCB, artillery reinforcement kept pace. By early January, the defenders could count on fire support from 46 artillery pieces of various calibers, five tanks armed with 90-mm guns, and 92 single or Ontos-mounted 106-mm recoilless rifles.[109] The base could also depend on fire support from US Army 175-mm guns located at Camp Carroll, east of Khe Sanh. Throughout the battle, Marine artillerymen fired 158,891 mixed rounds.[110][111][112] In addition, over 100,000 tons of bombs were dropped until mid-April by aircraft of the USAF, US Navy and Marines onto the area surrounding Khe Sanh.[113] This equates to roughly 1,300 tons of bombs dropped daily — 5 tons for every one of the 20,000 PAVN soldiers initially estimated to have been committed to the fighting at Khe Sanh.[114] Marine analysis of PAVN artillery fire estimated that the PAVN gunners had fired 10,908 artillery and mortar rounds and rockets into Marine positions during the battle.[115]

Communications with military command outside of Khe Sanh was maintained by an U.S. Army Signal Corps team, the 544th Signal Detachment from the 337th Signal Company, 37th Signal Brigade in Danang. The latest microwave/tropospheric scatter technology enabled them to maintain communications at all times. The site linked to another microwave/tropo site in Huế manned by the 513th Signal Detachment. From the Huế site the communication signal was sent to Danang headquarters where it could be sent anywhere in the world. The microwave/tropo site was located in an underground bunker next to the airstrip.[116]

Attacks prior to relief of the base

On the night of the fall of Lang Vei, three companies of the PAVN 101D Regiment moved into jump-off positions to attack Alpha-1, an outpost just outside the Combat Base held by 66 men of Company A, 1st Platoon, 1/9 Marines. At 04:15 on 8 February under cover of fog and a mortar barrage, the PAVN penetrated the perimeter, overrunning most of the position and pushing the remaining 30 defenders into the southwestern portion of the defenses. For some unknown reason, the PAVN troops did not press their advantage and eliminate the pocket, instead throwing a steady stream of grenades at the Marines.[103] At 07:40, a relief force from Company A, 2nd Platoon set out from the main base and attacked through the PAVN, pushing them into supporting tank and artillery fire.[117] By 11:00, the battle was over, Company A had lost 24 dead and 27 wounded, while 150 PAVN bodies were found around the position, which was then abandoned.[118]

On 23 February, KSCB received its worst bombardment of the entire battle. During one 8-hour period, the base was rocked by 1,307 rounds, most of which came from 130-mm (used for the first time on the battlefield) and 152-mm artillery pieces located in Laos.[119] Casualties from the bombardment were 10 killed and 51 wounded. Two days later, US troops detected PAVN trenches running due north to within 25 m of the base perimeter.[120] The majority of these were around the southern and southeastern corners of the perimeter, and formed part of a system that would be developed throughout the end of February and into March until they were ready to be used to launch an attack, providing cover for troops to advance to jumping-off points close to the perimeter.[56] These tactics were reminiscent of those employed against the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, particularly in relation to entrenching tactics and artillery placement, and the realization assisted US planners in their targeting decisions.[121][122]

Nevertheless, the same day that the trenches were detected, 25 February, 3rd Platoon from Bravo Company 1st Battalion, 26th Marines was ambushed on a short patrol outside the base's perimeter to test the PAVN strength. The Marines pursued three enemy scouts, who led them into an ambush. The platoon withdrew following a three-hour battle that left six Marines dead, 24 missing, and one taken prisoner.[120]

In late February, ground sensors detected the 66th Regiment, 304th Division preparing to mount an attack on the positions of the 37th ARVN Ranger Battalion on the eastern perimeter.[123] On the night of 28 February, the combat base unleashed artillery and airstrikes on possible PAVN staging areas and routes of advance. At 21:30, the attack came on, but it was stifled by the small arms of the Rangers, who were supported by thousands of artillery rounds and air strikes. Two further attacks later in the morning were halted before the PAVN finally withdrew. The PAVN, however, were not through with the ARVN troops. Five more attacks against their sector were launched during March.[123]

By mid-March, Marine intelligence began to note an exodus of PAVN units from the Khe Sanh sector.[123] The 325C Divisional Headquarters was the first to leave, followed by the 95C and 101D Regiments, all of which relocated to the west. At the same time, the 304th Division withdrew to the southwest. That did not mean, however, that battle was over. On 22 March, over 1,000 North Vietnamese rounds fell on the base, and once again, the ammunition dump was detonated.[124]

On 30 March, Bravo Company, 26th Marines, launched an attack toward the location of the ambush that had claimed so many of their comrades on 25 February. Following a rolling barrage fired by nine artillery batteries, the Marine attack advanced through two PAVN trenchlines, but the Marines failed to locate the remains of the men of the ambushed patrol. The Marines claimed 115 PAVN killed, while their own casualties amounted to 10 dead, 100 wounded, and two missing.[125] At 08:00 the following day, Operation Scotland was officially terminated. Operational control of the Khe Sanh area was handed over to the US Army's 1st Air Cavalry Division for the duration of Operation Pegasus.[115]

Cumulative friendly casualties for Operation Scotland, which began on 1 November 1967, were: 205 killed in action, 1,668 wounded, and 25 missing and presumed dead.[126] These figures do not include casualties among Special Forces troops at Lang Vei, aircrews killed or missing in the area, or Marine replacements killed or wounded while entering or exiting the base aboard aircraft. As far as PAVN casualties were concerned, 1,602 bodies were counted, seven prisoners were taken, and two soldiers defected to allied forces during the operation. American intelligence estimated that between 10,000 and 15,000 PAVN troops were killed during the operation, equating to up to 90% of the attacking 17,200-man PAVN force.[115][126] The PAVN acknowledged 2,500 men killed in action.[127] They also reported 1,436 wounded before mid-March, of which 484 men returned to their units, while 396 were sent up the Ho Chi Minh Trail to hospitals in the north.[18]

President Johnson orders that the base be held at all costs

The fighting at Khe Sanh was so volatile that the Joint Chiefs and MACV commanders were uncertain that the base could be held by the Marines. In the US, the media following the battle drew comparisons with the 1954 Battle of Dien Bien Phu, which proved disastrous for the French.[128][129] Nevertheless, according to Tom Johnson, President Johnson was "determined that Khe Sanh [would not] be an 'American Dien Bien Phu'". He subsequently ordered the US military to hold Khe Sanh at all costs. As a result, "B-52 Arc Light strikes originating in Guam, Okinawa, and Thailand bombed the jungles surrounding Khe Sanh into stubble fields" and Khe Sanh became the major news headline coming out of Vietnam in late March 1968.[130]

Operation Pegasus (1–14 April 1968)

Planning for the overland relief of Khe Sanh had begun as early as 25 January 1968, when Westmoreland ordered General John J. Tolson, commander, First Cavalry Division, to prepare a contingency plan. Route 9, the only practical overland route from the east, was impassable due to its poor state of repair and the presence of PAVN troops. Tolson was not happy with the assignment, since he believed that the best course of action, after Tet, was to use his division in an attack into the A Shau Valley. Westmoreland, however, was already planning ahead. Khe Sanh would be relieved and then used as the jump-off point for a "hot pursuit" of enemy forces into Laos.[131]

On 2 March, Tolson laid out what became known as Operation Pegasus, the operational plan for what was to become the largest operation launched by III MAF thus far in the conflict. The 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment (2/1 Marines) and the 2/3 Marines would launch a ground assault from Ca Lu Combat Base (16 km east of Khe Sanh) and head west on Route 9 while the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Brigades of the 1st Cavalry Division, would air-assault key terrain features along Route 9 to establish fire support bases and cover the Marine advance. The advance would be supported by 102 pieces of artillery.[132] The Marines would be accompanied by their 11th Engineer Battalion, which would repair the road as the advance moved forward. Later, the 1/1 Marines and 3rd ARVN Airborne Task Force (the 3rd, 6th, and 8th Airborne Battalions) would join the operation.[133]

Westmoreland's planned relief effort infuriated the Marines, who had not wanted to hold Khe Sanh in the first place and who had been roundly criticized for not defending it well.[134] The Marines had constantly argued that technically, Khe Sanh had never been under siege, since it had never truly been isolated from resupply or reinforcement. Cushman was appalled by the "implication of a rescue or breaking of the siege by outside forces."[135]

Regardless, on 1 April, Operation Pegasus began.[136] Opposition from the North Vietnamese was light and the primary problem that hampered the advance was continual heavy morning cloud cover that slowed the pace of helicopter operations. As the relief force made progress, the Marines at Khe Sanh moved out from their positions and began patrolling at greater distances from the base. Things heated up for the air cavalrymen on 6 April, when the 3rd Brigade encountered a PAVN blocking force and fought a day-long engagement.[137]

On the following day, the 2nd Brigade of the 1st Air Cavalry captured the old French fort near Khe Sanh village after a three-day battle. The link-up between the relief force and the Marines at KSCB took place at 08:00 on 8 April, when the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment entered the camp.[138] The 11th Engineers proclaimed Route 9 open to traffic on 11 April. On that day, Tolson ordered his unit to immediately make preparations for Operation Delaware, an air assault into the A Shau Valley.[137] At 08:00 on 15 April, Operation Pegasus was officially terminated.[139] Total US casualties during the operation were 92 killed, 667 wounded, and five missing. Thirty-three ARVN troops were also killed and 187 were wounded.[140] Because of the close proximity of the enemy and their high concentration, the massive B-52 bombings, tactical airstrikes, and vast use of artillery, PAVN casualties were estimated by MACV as being between 10,000 and 15,000 men.[141]

Lownds and the 26th Marines departed Khe Sanh, leaving the defense of the base to the 1st Marine Regiment. He made his final appearance in the story of Khe Sanh on 23 May, when his regimental sergeant major and he stood before President Johnson and were presented with a Presidential Unit Citation on behalf of the 26th Marines.[142][143]

Operation Scotland II

On 15 April, the 3rd Marine Division resumed responsibility for KSCB, Operation Pegasus ended, and Operation Scotland II began with the Marines seeking out the PAVN in the surrounding area.[139] Operation Scotland II would continue until 28 February 1969 resulting in 435 Marines and 3304 PAVN killed.[144]

Author Peter Brush details that an "additional 413 Marines were killed during Scotland II through the end of June 1968".[1] He goes on to state that a further 72 were killed as part Operation Scotland II throughout the remainder of the year, but that these deaths are not included in the official US casualty lists for the Battle of Khe Sanh. Twenty-five USAF personnel who were killed are also not included.[1]

Operation Charlie: evacuation of the base

The evacuation of Khe Sanh began on 19 June 1968 as Operation Charlie.[145] Useful equipment was withdrawn or destroyed, and personnel were evacuated. A limited attack was made by a PAVN company on 1 July, falling on a company from the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, who were holding a position 3 km to the southeast of the base. Casualties were heavy among the attacking PAVN, who lost over 200 killed, while the defending Marines lost two men.[146] The official closure of the base came on 5 July after fighting, which had killed five more Marines. The withdrawal of the last Marines under the cover of darkness was hampered by the shelling of a bridge along Route 9, which had to be repaired before the withdrawal could be completed.[7]

Following the closure of the base, a small force of Marines remained around Hill 689 carrying out mopping-up operations.[7] Further fighting followed, resulting in the loss of another 11 Marines and 89 PAVN soldiers, before the Marines finally withdrew from the area on 11 July.[1] According to Brush, it was "the only occasion in which Americans abandoned a major combat base due to enemy pressure" and in the aftermath, the North Vietnamese began a strong propaganda campaign, seeking to exploit the US withdrawal and to promote the message that the withdrawal had not been by choice.[1]

The PAVN claim that they began attacking the withdrawing Americans on 26 June 1968 prolonging the withdrawal, killing 1,300 Americans and shooting down 34 aircraft before "liberating" Khe Sanh on 15 July. The PAVN claim that during the entire battle they "eliminated" 17,000 enemy troops, including 13,000 Americans and destroyed 480 aircraft.[147]

Regardless, the PAVN had gained control of a strategically important area, and its lines of communication extended further into South Vietnam.[10] Once the news of the closure of KSCB was announced, the American media immediately raised questions about the reasoning behind its abandonment. They asked what had changed in six months so that American commanders were willing to abandon Khe Sanh in July. The explanations given out by the Saigon command were that "the enemy had changed his tactics and reduced his forces; that PAVN had carved out new infiltration routes; that the Marines now had enough troops and helicopters to carry out mobile operations; that a fixed base was no longer necessary."[148]

While KSCB was abandoned, the Marines continued to patrol the Khe Sanh plateau, including reoccupying the area with ARVN forces from 5–19 October 1968 with minimal opposition.[149] On 31 December 1968, the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion was landed west of Khe Sanh to commence Operation Dawson River West, on 2 January 1969 the 9th Marines and 2nd ARVN Regiment were also deployed on the plateau supported by the newly established Fire Support Bases Geiger and Smith; the 3-week operation found no significant PAVN forces or supplies in the Khe Sanh area.[150] From 12 June to 6 July 1969, Task Force Guadalcanal comprising 1/9 Marines, 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry Regiment and 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 2nd ARVN Regiment occupied the Khe Sanh area in Operation Utah Mesa.[151] The Marines occupied Hill 950 overlooking the Khe Sanh plateau from 1966 until September 1969 when control was handed to the Army who used the position as a SOG operations and support base until it was overrun by the PAVN in June 1971.[152][153] The gradual withdrawal of US forces began during 1969 and the adoption of Vietnamization meant that, by 1969, "although limited tactical offensives abounded, US military participation in the war would soon be relegated to a defensive stance."[154]

According to military historian Ronald Spector, to reasonably record the fighting at Khe Sanh as an American victory is impossible.[7] With the abandonment of the base, according to Thomas Ricks, "Khe Sanh became etched in the minds of many Americans as a symbol of the pointless sacrifice and muddled tactics that permeated a doomed U.S. war effort in Vietnam".[155]

Aftermath

Termination of the McNamara Line

Commencing in 1966, the US had attempted to establish a barrier system across the DMZ to prevent infiltration by North Vietnamese troops. Known as the McNamara Line, it was initially codenamed "Project Nine" before being renamed "Dye Marker" by MACV in September 1967. This occurred just as the PAVN began the first phase of their offensive, launching attacks against Marine-held positions across the DMZ. These attacks hindered the advancement of the McNamara Line, and as the fighting around Khe Sanh intensified, vital equipment including sensors and other hardware had to be diverted from elsewhere to meet the needs of the US garrison at Khe Sanh. Construction on the line was ultimately abandoned and resources were later diverted towards implementing a more mobile strategy.[9]

Assessment

The precise nature of Hanoi's strategic goal at Khe Sanh is regarded as one of the most intriguing unanswered questions of the Vietnam War. According to Gordon Rottman, even the North Vietnamese official history, Victory in Vietnam, is largely silent on the issue.[156] This question, known among American historians as the "riddle of Khe Sanh" has been summed up by John Prados and Ray Stubbe: "Either the Tet Offensive was a diversion intended to facilitate PAVN/VC preparations for a war-winning battle at Khe Sanh, or Khe Sanh was a diversion to mesmerize Westmoreland in the days before Tet."[157] In assessing North Vietnamese intentions, Peter Brush cites the Vietnamese theater commander, Võ Nguyên Giáp's claim "that Khe Sanh itself was not of importance, but only a diversion to draw U.S. forces away from the populated areas of South Vietnam".[158] This has led other observers to conclude that the siege served a wider PAVN strategy; it diverted 30,000 US troops away from the cities that were the main targets of the Tet Offensive.[159]

Whether the PAVN actually planned to capture Khe Sanh and whether the battle was an attempt to replicate the Việt Minh triumph against the French at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu has long been a point of contention. Westmoreland believed that the latter was the case and this belief was the basis for his desire to stage "Dien Bien Phu in reverse".[160] Those who agree with Westmoreland reason that no other explanation exists as to why Hanoi would have committed so many forces to the area instead of deploying them for the Tet Offensive. The fact that the North Vietnamese only committed about half of their available forces to the offensive (60–70,000), the majority of whom were VC, is cited in favor of Westmoreland's argument. Other theories argued that the forces around Khe Sanh were simply a localized defensive measure in the DMZ area, or that they were serving as a reserve in case of an offensive American end run in the mode of the American invasion at Inchon during the Korean War. However, North Vietnamese sources claim that the Americans did not win a victory at Khe Sanh, but they were forced to retreat to avoid destruction. The PAVN claimed that Khe Sanh was "a stinging defeat from both the military and political points of view": Westmoreland was replaced two months after the end of the battle and his successor explained the retreat in different ways.[7]

General Creighton Abrams has also suggested that the North Vietnamese may have been planning to emulate Dien Bien Phu. He believed that the PAVN's actions during Tet proved it.[161] He cited the fact that it would have taken longer to dislodge the North Vietnamese at Hue if the PAVN had committed the three divisions at Khe Sanh to the battle there (although the PAVN did commit three regiments to the fighting from the Khe Sanh sector), instead of dividing their forces.[162]

Another interpretation was that the North Vietnamese were planning to work both ends against the middle. This strategy has come to be known as the Option Play. If the PAVN could take Khe Sanh, all well and good for them. If they could not, they would occupy the attention of as many American and South Vietnamese forces in I Corps as they could to facilitate the Tet Offensive.[163] This view was supported by a captured (in 1969) North Vietnamese study of the battle. According to it, the PAVN would have taken Khe Sanh if they could, but the price they were willing to pay had limits. Their main objectives were to inflict casualties on US troops and to isolate them in the remote border regions.[164]

Another theory is that the actions around Khe Sanh (and the other border battles) were simply a feint, a ruse meant to focus American attention (and forces) on the border. General and historian Dave Palmer accepts this rationale: "General Giap never had any intention of capturing Khe Sanh ... [it] was a feint, a diversionary effort. And it had accomplished its purpose magnificently."[165][Note 7]

Marine General Rathvon M. Tompkins, commander of the 3rd Marine Division, has pointed out that had the PAVN actually intended to take Khe Sanh, PAVN troops could have cut the base's sole source of water, a stream 500 m outside the perimeter of the base. Had they simply contaminated the stream, the airlift would not have provided enough water to the Marines.[127] Marine Lieutenant General Victor Krulak seconded the notion that there was never a serious intention to take the base by also arguing that neither the water supply nor the telephone land lines were ever cut by the PAVN.[167][168]

One argument leveled by Westmoreland at the time (and often quoted by historians of the battle) was that only two Marine regiments were tied down at Khe Sanh compared with several PAVN divisions.[169] At the time Hanoi made the decision to move in around the base, though, Khe Sanh was held by only two (or even just one) American battalions. Whether the destruction of one battalion could have been the goal of two to four PAVN divisions was debatable. Yet, even if Westmoreland believed his statement, his argument never moved on to the next logical level. By the end of January 1968, he had moved half of all US combat troops—nearly 50 maneuver battalions—to I Corps.[170]

Use during Operation Lam Son 719

On 30 January 1971, the ARVN and US forces launched Operation Dewey Canyon II, which involved the reopening of Route 9, securing the Khe Sanh area and reoccupying of KSCB as a forward supply base for Operation Lam Son 719. On 8 February 1971, the leading ARVN units marched along Route 9 into southern Laos while the US ground forces and advisers were prohibited from entering Laos. US logistical, aerial, and artillery support was provided to the operation.[171][172] Following the ARVN defeat in Laos, the newly re-opened KSCB came under attack by PAVN sappers and artillery and the base was abandoned once again on 6 April 1971.[173][174]

References

Footnotes

- Not including ARVN Ranger, RF/PF, Forward Operation Base 3 – U.S. Army, Royal Laotian Army and SOG commandos losses. The low figure often cited for US casualties (205 killed in action, 443 wounded, 2 missing) does not take into account U.S. Army or Air Force casualties or those incurred during Operation Pegasus.[15]

- For a succinct overview of the creation of the CIDG program and its operations.[20]

- Only nine US battalions were available from Hue/Phu Bai northward.[44]

- Westmoreland had been forwarding operational plans for an invasion of Laos since 1966. First there had been Operation Full Cry, the original three-division invasion plan. This was superseded by the smaller contingency plans Southpaw and High Port (1967). With Operation El Paso the General returned to a three-divisional plan in 1968. Another plan (York) envisioned the use of even larger forces.[46][47]

- A myth has grown up around this incident. The dead men have been described as wearing Marine uniforms; that they were a regimental commander and his staff on a reconnaissance; and that they were all identified, by name, by American intelligence.[58]

- The official North Vietnamese history claimed that 400 South Vietnamese troops had been killed and 253 captured. It claimed, however, that only three American advisors were killed during the action.[99]

- This is also the position taken in the official PAVN history, but which offers no further explanation of the strategy.[166]

Citations

- Brush, Peter (2006). "Recounting the Casualties at Khe Sanh". Jean and Alexander Heard Library, Vanderbilt University. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013.

- "The Battle of Khe Sanh 40th Anniversary: Casualties in May 1968". Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "The Battle of Khe Sanh 40th Anniversary: Casualties in June 1968". Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Kelley, p. 5.

- Willbanks, p. 104.

- Dougherty, p. 236.

- Brush, Peter (12 June 2006). "The Withdrawal from Khe Sanh". HistoryNet. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "The Battle of Khe Sanh: 40th Anniversary: Casualties in November 1968". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

- "The McNamara Line". US History. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Rottman, p. 90.

- Staff (9 February 1968). "Khe Sanh: 6,000 Marines Dug In for Battle". Life. Time. pp. 26–29.

- Rottman, p. 51.

- Rottman, pp. 90–92.

- Tucker 2010, p. 2450.

- Prados and Stubbe, p. 454.

- Shulimson, pp. 234–235.

- Shore, p. 131.

- Prados, John. "Khe Sanh: The Other Side Of The Hill". The VVA Veteran. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014.

- Shulimson, p. 59.

- Stanton, pp. 35–48.

- Marino, James I. "Strategic Crossroads at Khe Sanh". HistoryNet. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Boston Publishing Company, p. 131.

- US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Command History 1965, Annex N. Saigon, 1966, p. 18.

- Prados, pp. 140–146

- Dougan, Weiss, et al., p. 42.

- Shulimson, p. 60.

- Eggleston, pp. 16–122.

- Telfer, Rogers, and Fleming, pp. 129–131.

- Maitland and McInerney, p. 164.

- Maitland and McInerney, p. 165.

- Stanton, pp. 160–169.

- Maitland and McInerney, p. 183.

- Palmer, pp. 213–215.

- Dougan and Weiss, p. 432.

- Murphy 2003, pp. 3–7, 13–14.

- Telfer, Rogers, and Fleming, p. 33.

- Murphy 2003, p. 79.

- Shore, p. 17.

- Shulimson, pp. 60–61.

- Murphy 1997 p. 165.

- Long 2016, p. 125.

- Prados, p. 155.

- Murphy 2003, p. 233.

- Prados and Stubbe, p. 159.

- Westmoreland, p. 236.

- US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Command History, 1966, Annex M. Saigon, 1967, p. 60.

- Van Staaveren, pp. 230 & 290.

- Shulimson, p. 67.

- Shore, p. 47.

- Dougan and Weiss p. 42.

- Clarke, p. 146.

- Clarke, p. 46.

- Dougan and Weiss, p. 43.

- Military Institute of Vietnam, p. 216.

- Shore, pp. 58–59.

- Barry, William A. "Air Power in the Siege of Khe Sanh". HistoryNet. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- Shore, p. 72.

- Prados and Stubbe, p. 215.

- Shore, pp. 30–31.

- Shore, p. 31.

- Shulimson, p. 72.

- Shulimson, pp. 258–259.

- Dougan and Weiss, p. 44.

- Shulimson, p. 261.

- Shulimson, p. 260.

- Shulimson, p. 261-4.

- Shulimson, pp. 260–261.

- Shulimson, p. 269.

- Nalty, p. 107.

- Shulimson, p. 270.

- Ehrlich, Richard (17 April 2008). "The US's secret plan to nuke Vietnam, Laos". Asia Times. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- McNamara, Robert. "Memorandum for the President, 19 February 1968". Khe Sanh Declassified Documents. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Van Staaveren, p. 290.

- Pearson, p. 35.

- Shore, pp. 93–94.

- Nalty, pp. 66–67.

- Morocco, p. 52.

- Morocco, p. 178.

- Prados, p. 301.

- Nalty, p. 95.

- Prados, p. 297.

- Westmoreland, p. 252.

- Shulimson, pp. 487–515.

- Prados, pp. 295–297.

- Nalty, pp. 68–69.

- Prados, p. 223.

- Prados, p. 295.

- Donaldson, p. 115.

- Prados, p. 286.

- Pisor, p. 152.

- Pike 2013, p. 35.

- Plaster, p. 154

- Prados, pp. 319–320.

- Prados, p. 329.

- Shulimson, p. 276.

- Prados, pp. 332–333.

- Prados, p. 333.

- Dougan and Weiss, p. 47.

- Military History Institute of Vietnam, p. 222.

- Shulimson, pp. 276–277.

- Prados, p. 338.

- Prados, p. 340.

- Shulimson, p. 277.

- Pisor, p. 76.

- Shore, p. 90.

- Dougan and Weiss, p. 49.

- Shore, p. 79.

- Shore, p. 89.

- Shore, p. 33.

- Shore, p. 107.

- Browne, Malcolm W. (13 May 1994). "Battlefields of Khe Sanh: Still One Casualty a Day". New York Times. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Ankony, pp.145–155.

- Anderson, Ray and Brush, Peter. "The US Army Quartermaster Air Delivery Units and the Defense of Khe Sanh". Vietnam Airdrop History. Retrieved 5 October 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Operation Niagara: Siege of Khe Sanh". HistoryNet. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Shulimson, p. 283.

- "1st Signal Brigade". Army Historical Foundation. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Prados, p. 348.

- Shulimson, p.278.

- Shulimson, p. 279.

- Shulimson, pp. 279–280.

- Wirtz, p.197.

- Shore, p. 111.

- Shulimson, p. 281.

- Shulimson, p. 282.

- Shulimson, pp. 282–283.

- Shore, p.131

- Dougan and Weiss, p. 55.

- Ryan 1984, p.75.

- Welburn 1996, p. 51.

- Johnson, Chapter 18.

- Prados, pp. 418–420.

- Prados, p. 428.

- Prados, p. 419.

- Murphy 2003, pp. 239–240. See also Pisor, p. 108.

- Murphy 2003, p. 240.

- Shulimson, p. 284.

- Shulimson, p. 287.

- Shulimson, p. 286.

- Shulimson, p. 289.

- Sigler, p. 72.

- Tucker 1998, p. 340.

- Shulimson, pp. 287–289.

- Jones, Chapters 21 & 22.

- Smith, Charles (1988). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: High Mobility and Standdown 1969. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. p. 23. ISBN 9781494287627.

- Shulimson, p. 324.

- Shulimson, p. 326.

- Military History Institute of Vietnam (2002). Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975. trans. Pribbenow, Merle. University of Kansas Press. pp. 229–30. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- Dougan and Weiss, p. 54.

- Shulimson, pp. 409–410.

- Smith, pp. 18–19.

- Smith, pp. 71–72.

- Smith, p. 152.

- Long 2013, pp. 355–362.

- Stanton, p. 246.

- Ricks, Thomas E. (5 June 2014). "5 things you didn't know about Khe Sanh". FP. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Rottman, Opposing plans.

- Prados, p. 173.

- Brush, Peter. "The Battle of Khe Sanh". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- Page and Pimlott, p. 324.

- Pisor, p. 61.

- Warren, p. 333.

- Dougan and Weiss, p. 38.

- Pisor, p. 210.

- Shulimson, pp. 67–68.

- Palmer, p. 219.

- Military History Institute of Vietnam, pp. 216–217.

- Krulak, p. 218.

- Shulimson p. 289.

- Pisor, p. 240.

- Murphy 2003, p. 235.

- Hinh, pp. 8–12.

- Nolan, p. 31.

- 8th Battalion, 4th Artillery (9 May 1971). "Operational Report Lessons Learned, Headquarters, 8th Battalion 4th Artillery, Period Ending 30 April 1971". Department of the Army. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Thies, Donald E. "Narrative of Events of Company B, 2nd Battalion, 506th Infantry, 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile) During LAM SON 719". Retrieved 4 October 2017.

Sources

Unpublished government documents

- US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Command History 1965, Annex N. Saigon, 1966.

- US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, Command History 1966, Annex M. Saigon, 1967.

Published government documents

- Hinh, Nguyen Duy (1979). Operation Lam Sơn 719. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 227845251.

- Military History Institute of Vietnam (2002). Victory in Vietnam: A History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954–1975. trans. Pribbenow, Merle. Lawrence KS: University of Kansas Press. ISBN 0-7006-1175-4.

- Nalty, Bernard C. (1986). Air Power and the Fight for Khe Sanh (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2003. LCC DS557.8.K5 N34 1986

- Pearson, Willard (2013) [1975]. The War in the Northern Provinces 1966–1968. Vietnam Studies. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-092093-6.

- Shore, Moyars S. III (1969). The Battle of Khe Sanh. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Marine Corps Historical Branch. OCLC 923350777.

- Shulimson, Jack; Blaisol, Leonard; Smith, Charles R.; Dawson, David (1997). The U.S. Marines in Vietnam: 1968, the Decisive Year. Washington, D.C.: History and Museums Division, United States Marine Corps. ISBN 0-16-049125-8.

- Telfer, Gary L.; Rogers, Lane; Fleming, V. Keith (1984). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: 1967, Fighting the North Vietnamese. Washington, D.C.: History and Museums Division, United States Marine Corps. LCC DS558.4 .U55 1977

- Van Staaveren, Jacob (1993). Interdiction in Southern Laos, 1961–1968. Washington, D.C.: Center of Air Force History. LCC DS558.8 .V36 1993

Autobiographies

- Westmoreland, William C. (1976). A Soldier Reports. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-00434-6.

Secondary sources

- Ankony, Robert C. (2009). Lurps: A Ranger's Diary of Tet, Khe Sanh, A Shau, and Quang Tri (Revised ed.). Landham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-76184-373-3.

- Boston Publishing Company (2014). The American Experience in Vietnam: Reflections on an Era. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-76034-625-9.

- Clarke, Bruce B. G. (2007). Expendable Warriors – The Battle of Khe Sanh and the Vietnam War. Westport, Connecticut & London: Praeger International Security. ISBN 978-0-275-99480-8.

- Donaldson, Gary (1996). America at War Since 1945: Politics and Diplomacy in Korea, Vietnam, and the Gulf War. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27595-660-8.

- Dougherty, Martin J. (2012). 100 Battles, Decisive Battles that Shaped the World. Bath: Parragon. ISBN 978-1-44546-763-4.

- Dougan, Clark; Weiss, Stephen; et al. (1983). Nineteen Sixty-Eight. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-06-9.

- Eggleston, Michael A. (2017). Dak To and the Border Battles of Vietnam, 1967–1968. McFarland. ISBN 978-147666-417-0.

- Johnson, Tom A. (2006). To the Limit: An Air Cav Huey Pilot in Vietnam. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-446-2.

- Jones, Gregg (2014). Last Stand at Khe Sanh – The US Marines' Finest Hour in Vietnam. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82139-4.

- Kelley, Michael P. (2002). Where We Were in Vietnam. Hellgate Press. ISBN 1-55571-625-3.

- Krulak, Victor (1984). First to Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-161-0.

- Long, Austin (2016). The Soul of Armies: Counterinsurgency Doctrine and Military Culture in the US and UK. London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-50170-390-4.

- Long, Lonnie (2013). Unlikely Warriors: The Army Security Agency's Secret War in Vietnam 1961–1973. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4759-9059-1.

- Maitland, Terrence; McInerney, John (1983). A Contagion of War. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-05-0.

- Morocco, John (1984). Thunder from Above: Air War, 1941–1968. Boston: Boston Publishing Company. ISBN 0-939526-09-3.

- Murphy, Edward F. (2003). The Hill Fights:The First Battle of Khe Sanh. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-129910-828-8.

- Murphy, Edward F. (1997). Semper Fi: Vietnam: From Da Nang to the DMZ, Marine Corps Campaigns, 1965–1975. Random House. ISBN 978-0-30741-661-2.

- Nolan, Keith William (1986). Into Laos: The Story of Dewey Canyon II/Lam Son 719. Novato CA: Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0-89141-247-2.

- Page, Tim; Pimlott, John (1988). Nam – The Vietnam Experience. New York: Mallard Press. ISBN 978-0-79245-003-0.

- Palmer, Dave Richard (1978). Summons of the Trumpet: The History of the Vietnam War from a Military Man's Viewpoint. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-34531-583-0.

- Pike, Thomas F. (2013). Military Records, February 1968, 3rd Marine Division: The Tet Offensive. ISBN 978-1-4812-1946-4.

- Pike, Thomas F. (2015). Operations and Intelligence, I Corps Reporting: February 1969. ISBN 978-1-5194-8630-1.

- Pike, Thomas F. (2017). I Corps Vietnam: An Aerial Retrospective. ISBN 978-1-366-28720-5.

- Pisor, Robert (1982). The End of the Line: The Siege of Khe Sanh. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-34531-092-7.

- Plaster, John L. (1997). SOG: The Secret Wars of America's Commandos in Vietnam. New York: New American Library. ISBN 0-451-23118-X.

- Prados, John; Stubbe, Ray (1991). Valley of Decision: The Siege of Khe Sanh. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-395-55003-3.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Khe Sanh 1967–68: Marines Battle for Vietnam's Vital Hilltop Base. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-863-2.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2006). Viet Cong and NVA Tunnels and Fortifications of the Vietnam War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-003-X.

- Ryan, Rapheal (1984). "The Siege of Khe Sanh". Military History. 2 (2: February): 74–81.

- Sigler, David Burns (1992). Vietnam Battle Chronology: U.S. Army and Marine Corps Combat Operations, 1965–1973. Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1706-4.

- Smith, Charles (1988). U.S. Marines in Vietnam: High Mobility and Standdown 1969. History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. ISBN 978-1-4942-8762-7.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1985). Green Berets at War: U.S. Army Special Forces in Southeast Asia, 1956–1975. Novato, California: Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0-89141-238-0.

- Stanton, Shelby L. (1985). The Rise and Fall of an American Army: U.S. Ground Forces in Vietnam, 1965–1973. New York: Dell. ISBN 0-89141-232-8.

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Volume 6: 1950–2008. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. OCLC 838055731.

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. (1998). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Volume One. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0874369835.

- Warren, James (2005). "The Mystery of Khe Sanh". In Robert Cowley (ed.). The Cold War: A Military History. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-30748-307-2.

- Welburn, Chris (1996). "Vietnam Sieges: Dien Bien Phu and Khe Sanh – Any Comparison?". Australian Defence Force Journal (119: July/August): 51–63. ISSN 1320-2545.

- Willbanks, James H. (2008). The Tet Offensive: A Concise History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12841-4.

- Wirtz, James J. (2017). The Tet Offensive: Intelligence Failure in War. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-50171-335-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Khe Sanh. |

- Bibliography: The Tet Offensive and the Battle of Khe Sanh

- PBS.org – the Siege of Khe Sanh (extensive information on the battle)

- US Government-produced film on The Battle of Khe Sanh

- USMC CAP Oscar (extensive information on the CAP program and the CAP Company at Khe Sanh)

- Vietnam-war.info – the Siege of Khe Sanh (mainly details of battle)