1973 Paris Air Show Tu-144 crash

The 1973 Paris Air Show Tu-144 crash was the destruction of the second production Tupolev Tu-144 at Goussainville, Val-d'Oise, France, which killed all six crew and eight people on the ground.[1][2] The crash, at the Paris Air Show on Sunday, 3 June 1973,[3] damaged the development program of the Tupolev Tu-144.[4]

CCCP-77102, the Tu-144S involved in the accident, seen at the 1973 Paris Air Show, the day before the accident | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 3 June 1973 |

| Summary | Structural failure in flight due to sharp manoeuvres |

| Site | Goussainville, Val-d'Oise 49°01′33″N 2°28′28″E |

| Total fatalities | 14 |

| Total injuries | 60 |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Tupolev Tu-144S |

| Operator | Aeroflot |

| Registration | CCCP-77102 |

| Flight origin | Paris–Le Bourget Airport |

| Destination | Paris–Le Bourget Airport |

| Occupants | 6 |

| Passengers | 0 |

| Crew | 6 |

| Fatalities | 6 |

| Survivors | 0 |

| Ground casualties | |

| Ground fatalities | 8 |

| Ground injuries | 60 |

One theory is that a French Mirage jet sent to photograph the aircraft without the knowledge of the Soviet crew caused the pilots to take evasive manoeuvres, resulting in the crash.[5] Another theory is that in a rivalry with the Anglo-French Concorde, the pilots attempted a manoeuvre that was beyond the capabilities of the aircraft.[5][6]

Accident

The aircraft involved was Tupolev Tu-144S CCCP-77102, manufacturer's serial number 01–2, the second production Tu-144.[7] The aircraft had first flown on 29 March 1972.[8] This aircraft had been modified compared to the initial prototype to include landing gear that retracted into the nacelles, and retractable canards.[9] The pilot was Mikhail Kozlov,[6] and the co-pilot was Valery M. Molchanov.[10] Also on board were G. N. Bazhenov, the flight navigator, V. N. Benderov, deputy chief designer and engineer major-general, B. A. Pervukhin, senior engineer, and A. I. Dralin, flight engineer.[11] The crash occurred in front of 250,000 people, including designer Alexei Tupolev, toward the end of the show.[6]

During the show, there was a "fierce competition between the Anglo-French Concorde and the Russian Tu-144".[6] The Soviet pilot, Mikhail Kozlov, had bragged that he would outperform the Concorde.[6] "Just wait until you see us fly," he was quoted as saying. "Then you'll see something."[12] On the final day of the show, the Concorde, which was not yet in production, performed its demonstration flight first.[6] Its performance was later described as being unexciting, and it has been theorized that Kozlov was determined to show how much better his aircraft was.[12]

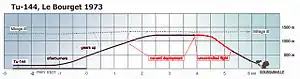

Once in flight, the aircraft made what appeared to be a landing approach, with the landing gear out and the "moustache" canards extended, but then with all four engines full power, climbed rapidly. Possibly stalling below 2,000 ft (610 m), the aircraft pitched over and went into a steep dive.[6] Trying to pull out of the subsequent dive with the engines again at full power, the Tu-144 broke up in mid-air, possibly due to overstressing the airframe. The left wing came away first, and then the aircraft disintegrated and crashed,[6][8][10] destroying 15 houses,[13] and killing all six people on board the Tu-144 and eight more on the ground.[8] Three children were among those killed, and 60 people received severe injuries.[14]

Aftermath

The crew of the Tu-144 were buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow on 12 June 1973.[15]

Following the crash, Marcel Dassault called for the 1975 Paris Air Show to be held at Istres, which is situated in open country 40 km (25 mi) north west of Marseille.[16]

The crash reduced the enthusiasm of Aeroflot for the Tu-144. Restrictions on the Tu-144 following the Paris Air Show crash meant that it only saw limited service during 1977 and 1978, and it was finally withdrawn following another crash in May 1978.[7] The Tu-144's rival, the Concorde, went on to serve with British Airways and Air France for 30 years afterwards, being finally withdrawn from service in 2003 due to low passenger numbers following the crash of Flight 4590, rising service costs and the slump in the aviation industry following the September 11 attacks.[17]

Causes

Investigation

The accident was investigated by the DTCE, part of the French military, which was responsible for accidents involving prototype aircraft in France. The wreckage was recovered to a hangar at Le Bourget, with some of it being flown by an Antonov An-22 to the Soviet Union.[10]

Theories

One theory is that the Tu-144 manoeuvred to avoid a French Mirage chase plane that was attempting to photograph its unique canards,[18] which were advanced for the time, and that the French and Soviet governments colluded with each other to cover up such details.[14] The flight of the Mirage was denied in the original French report of the incident, perhaps because it was engaged in industrial espionage. More recent reports have admitted the existence of the Mirage (and the fact that the Soviet crew were not told about the Mirage's flight) though not its role in the crash. However, the official press release did state: "though the inquiry established that there was no real risk of collision between the two aircraft, the Soviet pilot was likely to have been surprised."[14] Howard Moon, author of Soviet SST: The Techno-Politics Of The Tupolev-144, stresses that last-minute changes to the flight schedule would have disoriented the pilots in a cockpit with notably poor sightlines. He also cites an eyewitness who claims the co-pilot had agreed to take a camera with him, which he may have been operating at the time of the evasive manoeuvre.[14] The initial approach may have been an attempted landing on the wrong runway, which occurred due to a last-minute shortening of the Tu-144's display.[5]

An important contributing factor could be that control surfaces deflection had been de-restricted before the flight, perhaps to allow a more impressive demonstration, giving way for a bug of the electronics flight controls which deflected the elevons 10 degrees down after the retraction of the canards, causing the sudden dive.[8]

Bob Hoover, a pilot on the supersonic Bell X-1 program, believed that the rivalry of the Tu-144 and Concorde led the pilot of the Tu-144 to attempt a manoeuvre that went beyond the abilities of the aircraft: "That day, the Concorde went first, and after the pilot performed a high-speed flyby, he pulled up steeply and climbed to approximately 10,000 [feet] before leveling off. When the Tu-144 pilot performed the same manoeuvre he pulled the nose up so steeply l didn't believe he could possibly recover."[5]

Another theory claims that there was deliberate misinformation on the part of the Anglo-French design-team. The main thrust of this theory was that the Anglo-French team knew that the Soviet team was planning to steal the design plans of the Concorde, and the Soviets were allegedly passed false blueprints with a flawed design. The case, it is claimed, contributed to the imprisonment by the Soviets of Greville Wynne in 1963 for spying.[19][20] Wynne was imprisoned on 11 May 1963 and the development of the Tu-144 was not sanctioned until 16 July.

References

- "Russian SST crashes". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington, U.S.). Associated Press. 4 June 1973. p. 1.

- "Soviet SST crash kills 14". Milwaukee Sentinel. (Wisconsin, U.S.). UPI. 4 June 1973. p. 1.

- "15 killed as Russia's Concorde explodes". Glasgow Herald. 4 June 1973. p. 1.

- " Crash of the Tupolev 144 on 3 June 1973 video." ORTF, 8:00 p.m. news broadcasting, 3 June 1973, on the INA website , ina.fr.

- Zarakohvich, Yuri (7 August 2000). "The Concordski TU-144: A blast from the past". Time Europe. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- Gunston, Bill (7 June 1973). "Concordski and Concorde". New Scientist. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- Greenwood, John T. (1998). "The Designers and their Aircraft". In Robin D. S. Higham; John T. Greenwood; Von Hardesty (eds.). Russian aviation and air power in the twentieth century. Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7146-4784-5.

- Ranter, Harro. "CCCP-77102 Accident description". aviation-safety.net. Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Owen, Kenneth (2001). "The rivals". Concorde: story of a supersonic pioneer. Science Museum. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-900747-42-4.

- "Tu-144 crash investigation". Flight International: 908. 14 June 1973.

- "Once Upon a Time". Kommersant. 3 June 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- "DISASTERS: Deadly Exhibition". Time. 18 June 1973.

- "Paris Air Show: 100 years of Paris air show highlights". Flightglobal. 5 June 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- "Supersonic Spies." Nova PBS air date: 27 January 1998.

- "Tu-144 investigation continues". Flight International. 103 (3354): 938. 21 June 1973. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- "Display dangers". Flight International. 103 (3353): 910. 14 June 1973.

- "Concorde grounded for good". BBC News. 10 April 2003. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Smith, Patrick (24 June 2005). "Ask the pilot". Salon. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- Wynne, Greville. The Man from Odessa. Dublin: Warnock Books, 1983. ISBN 0-586-05709-9.

- Wright, Peter and Paul Greengrass.Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer. London: Viking, 1987. ISBN 0-670-82055-5.