2018 Japan–South Korea radar lock-on dispute

The 2018 Japan–South Korea radar lock-on dispute is about an incident between a Japanese aircraft and a South Korean vessel. The aircraft was part of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), while the vessel was part of the Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN). The event occurred on 20 December 2018, without the firing of any weapon, and was followed by a large diplomatic dispute between Japan and South Korea.

| 2018 Japan–South Korea radar lock-on dispute | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Ministry of Defense released a video of the scene taken from P-1. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Republic of Korea Navy Korea Coast Guard | Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 destroyer 1 Coast Guard Vessel | 1 maritime patrol aircraft | ||||||

.png.webp)

| Japan–South Korea radar lock-on dispute South Korean Navy radar lock-on incident | |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanji | 韓国海軍レーダー照射問題 | ||||

| Hiragana | かんこくかいぐんレーダーしょうしゃもんだい | ||||

| |||||

| Korean name | |||||

| Hangul | 한일해상군사분쟁 | ||||

| Hanja | 韓日海上軍事紛爭 | ||||

| |||||

Incident

The Government of Japan stated [3] a Republic of Korea Navy destroyer, ROKS Gwanggaeto the Great (DDH-971 광개토대왕),[4] allegedly directed its fire-control radar (STIR-180 similar to AN/SPG-55) at a maritime patrol aircraft, Kawasaki P-1 belonging to the Fleet Air Wing 4 of JMSDF, which was conducting surveillance off the Noto Peninsula in the Sea of Japan on Thursday 20 December 2018 at around 3:00 p.m. (JST).[3][5] claiming that aiming the fire-control radar at a plane is violation of the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES),[6] pointing out a lock with the FC radar is generally considered as a hostile act one step before actual firing.[7] The Ministry of Defense (MOD) explained the irradiation of the P-1 plane by the radar hit multiple times continuously over a certain period.[4]

In contrast, the Government of South Korea denied Japan's claims, stating that it did not operate STIR-180 radar (FC radar) but MW08 radar for the rescue when the Japanese plane arrived at the site. MW08 radar is a 3D radar for medium-range air and surface surveillance, target acquisition and tracking, capable of gun control against surface targets.[8] MW08 is regarded as an FC radar, but it is not connected with the fire-control system in the destroyer.[9][10] In addition, the South Korea claimed that the aircraft made a threatening "8-shape" flight by continuously flying with 500 meter (approximately 1600 feet) distance and 150 meter (approximately 500 feet) altitude while the warship was participating in the rescue of a distressed North Korean fishing boat.[11]

Timeline

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

2018

- On 20 December, the Japanese Ministry of Defense (MoD) claimed a Kawasaki P-1 maritime patrol aircraft from Fleet Air Wing 4 of the JMSDF was irradiated several times for a few minutes by a destroyer of the Republic of Korea Navy with a FCR. The incident occurred off the Noto Peninsula within a joint fishing zone of the two countries,[12] surrounded by both countries Exclusive economic zone,[13][14] away from the disputed Liancourt Rocks. After receiving the radiation, the P-1 patrol aircraft tried repeatedly to contact the other party by radio to ascertain their intentions, but got no response from the South Korean naval ship.[15]

- On 21 December, the Japanese Minister of Defense, Takeshi Iwaya, held a press conference to clarify the facts of the incident. While he told the reporters that the intention of the Korean side was not clearly understood, he criticized the incident as an extremely dangerous action.[16][17]

- On 22 December, the Japanese MoD conducted a careful and detailed analysis of the incident, and concluded that the irradiation was from STIR-180, which is unsuitable for broad searches.[18] Accordingly, the MoD stated that irradiation with a FCR was a very dangerous action that could lead to unexpected contingencies. Even though it had been searching for a ship in distress, it greatly endangered other ships and aircraft in the vicinity. The Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES), which both Japan and South Korea have adopted, suggests avoiding any radar irradiation from a FCR to aim at ships and aircraft.[18] For these reasons, Japan strongly requested South Korea prevent any recurrence of the incident.

- On 22 December, Korean Ministry of National Defense (MND) announced that they did not use the FCR (STIR-180) but it was operating an MW08 radar with the surveillance and tracking functions. Korean MND also claimed that there was no intent to aim it at the Japanese aircraft.[6][19]

- On 23 December, Korean MND argued that it had already explained its position to Japan and would strive harder to ensure that there would not be any "misunderstanding".[20]

- On 23 December, the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tarō Kōno, withheld any direct criticism, and announced that he would like to ask the Government of South Korea to respond to the incident in order to prevent relations between Japan and South Korea deteriorating.

- On 24 December, the Director-General of the Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kenji Kanasugi, visited the South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs to express Japan's strong regret and make a request for the prevention of the recurrence of this kind of incident. The Government of South Korea continuously denied the usage of STIR-180 while admitting the usage of MW08 for the rescue.[21][22] After the statement of the Government of South Korea, Takeshi Iwaya pointed out at a press conference that the Government of South Korea had some misunderstanding about the incident, and published a statement by the Japanese MoD that the maritime patrol aircraft had been repeatedly irradiated with electromagnetic waves characteristic of a FCR continuously for certain periods.[23][24]

- On 26 December, a member of the South Korean minor progressive Justice Party accused the Japanese Government, particularly the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, of "trying to antagonize South Korea by making up the allegation that the radar was pointed at the patrol plane."[25]

- On 27 December, Japan and South Korea held working-level teleconference over this issue between Mr. Hidehiro Ikematsu (Joint Staff Principal Councilor of the Japanese MoD) and Major General Kim Jeong-yoo (Operations Director of the Korean JCS), etc.[26] According to the informed sources of the Korean military, Both JMSDF and ROKN proposed to bring data received by Japanese aircraft and information on radar equipped by Korean destroyers, but they failed to meet an agreement due to security problem.[27][28] According to the release of the Korean MND, the defense authorities of the two nations "exchanged opinions regarding the truth and technical analysis to remove misunderstandings.", and agreed "to continue consultations on the matter. In case the two sides fail to settle the conflict through working-level talks, higher-level meetings could be held later"[29]

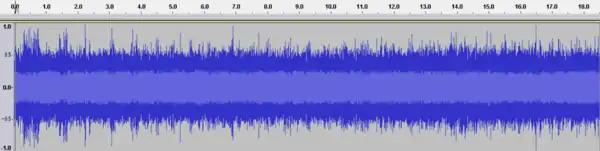

- On 28 December, the Japanese MoD released a video taken by the maritime patrol aircraft during the incident.[7][15] The video shows that a crewmember asked the destroyer in English several times via three frequencies(international VHF (156.8 MHz) and emergency frequencies 121.5 MHz and 243 MHz) about the FC antenna directed at the P-1, but the destroyer stayed silent. The video also shows the gray destroyer sailing near a pair of rubber boats and a North Korean vessel.[7] Sankei Shimbun reported that Japanese Prime Minister Abe had directed Japanese Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya to release the video publicly, though the Defense Minister was reluctant to release the video, worrying about a possible backlash from South Korea.[30] Korean MND expressed deep concerns and regrets over Japan's release of video footage related to an ongoing military radar spat just one day after two governments started a "working level conference" on 27 December, and accused Tokyo of releasing "inaccurate" facts.[31] Korean MND argued that "The video material released by Japan contains only footage of the Japanese patrol plane circling above the surface of the sea and the (audio) conversation between the pilots and it cannot by common sense be regarded as objective evidence supporting the Japanese claims. There's no change to the fact that our military did not operate tracking radar on a Japanese patrol plane."

2019

- On 2 January, Korean MND released a statement demanding an apology from Japan that the P-1 patrol aircraft was flying dangerously low over their naval destroyer.[32]

- On 4 January, Japanese Foreign Minister Taro Kono and Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha agreed over a phone conference to resolve the issue through "consultations between their military authorities".[33] Korean MND released a video criticizing Japan for the low flying altitude of the maritime patrol aircraft. The video also claimed that the Korean destroyer did not illuminate any tracking radar. The video mainly consists of the materials released by the Japanese MoD a week before.

- On 8 January, Japanese Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya repeatedly commented that Japan would be able to exchange radar wave records with the South Korean military to deepen discussion with South Korea.[34]

- On 14 January, Japan and South Korea held conference at Singapore. At this conference, some of misunderstandings were explained like the communication, later found that the communication personnel in the destroyer had misheard the radio communication.[35] Both countries suggested to analyze recorded data together, but they did not reach an agreement on major issues: about the usage of the radar and the threatening flight. The radar problem couldn't be resolved; the dissatisfaction of Japanese side about the radar was that Japan was asked to present the record of the RWR record first, not exchanging the records of both countries at the same time to avoid forgery, and the discontent of Korean side was that the Japan will show only a part of the P-1's record, excluding received frequencies,[36] while Korean side was asked to disclose entire radars' specification and frequencies of the destroyer.[37][38][39][40] About the matter of the threatening flight, Japan claimed "the MSDF P-1 maintained (even at its closet flight) a sufficiently safe altitude (approx.150m) and distance (approx. 500m) from the ROK destroyer" and requested ROK for the objective evidence to support their claim, but ROK had failed to provide such evidence and had repeatedly responded “if the subject of the threat feels threatened, it is then a threat," [35] while Korean MND claimed that "safe altitude (approx.150m) and distance (approx. 500m)" is based on ICAO applying to civil flight, not a flight made by a government. They also claimed that when flights with altitude and distance admitted by Japanese were made to Japanese ship, JMSDF would also protest. Although Japanese MoD replied that they would not protest against it,[41] Japan didn't acknowledge it as an official statement when Korean representatives asked whether they can declare it internationally.[42] Both Japan and South Korea promised to hold further negotiations.

- On 21 January, Japanese MoD released the final statement regarding this incident including the location-relationship-diagram and the sound file of the radar reception(also known as RWR records). Japanese MoD also pointed out that this sound file evidence(RWR records) was rejected to be examined by Korean MND at the time of working-level consultations held on 14 January.[35] After Japan's final statement, Choi hyon-su, official spokesperson of Korean MND, on the official regular briefing, stated "(from the sound records released on January.21) We couldn't interpret the sound records since we were not passed conversion logs for the records from Japan,[43][44] and RWR reception record cannot exactly prove the usage of STIR-180 since various radars were used at the time, like Kelvin radar making similar frequencies, using I-band, in Sambongho, Korea Coast Guard's vessel, and MW08 that can be identified as FC radar, that could have confused P-1's ESM recorder."[45][46] Japan declared there would be no more working-level consultations while Korean MND suggesting further joint investigations comparing each countries' data.[47]

- On 22 January, Korean MND released the formal statement summarizing their previous arguments explaining issues about the radar and the flight. Korean MND stated "The fundamental nature of this issue is the JMSDF patrol aircraft's threatening low-altitude flight towards the ROK Navy vessel that had been conducting a humanitarian rescue operation. ... We express our deepest regrets to Japan for discontinuing the working-level meetings without providing any decisive evidence. Along with the solid ROK-US Combined Defense Posture, our government will continue its efforts to strengthen security cooperation between the ROK and Japan despite the current incident."[44]

- On 23 January, according to the Korean MND, a Japanese patrol aircraft flew at an altitude of 200–230 feet (61–70 m) within 1,800 feet (550 m) of a South Korean naval vessel on the afternoon of 23 January off Socotra Rock (Iŏdo) in the Yellow Sea, which lies some 100 miles (160 km) southeast of the South Korean island, Jeju.[48] The South Korean military called this action a "clear provocation" that "if such activity repeats again, our military will respond strongly based on our response rules." The Japanese Defense Minister denied the allegation, saying "the altitude of the Japanese aircraft claimed by Korea, 200–230 feet (61–70 m), is not accurate, we are properly recording our flight. The Japanese aircraft was flying higher than altitude of 150 meters, following the international and domestic law.[49] Japan Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga encouraged better communication between the military forces of the two countries.[50]

- On 24 January, Korean MND released 5 pictures taken by a camcorder and a thermal camera connected with a radar in the destroyer with recorded height and distance of the patrol plane.Korean MND explained that it detected the exact altitude and distance using a maritime surveillance radar.[51] [52] Japan stated that (regarding the photo with Japanese patrol aircraft P3C) it does not prove the altitude of the aircraft since the surface of the sea is not included in the picture.[53]

- On 25 January, the spokesperson of Korean MND, Choi hyon-su stated, "If Japan cannot trust our radar data that we revealed in yesterday, Japan should suggest more reliable evidence."[54] Japan stated "We have no reason or intention to threaten Korea's destroyer. If the two approaches, our patrol aircraft is not armed and the other is the destroyer, the unarmed will feel more threatened"[55][56]

- On 27 January, Korean Minister of National Defense Jeong Kyeong-doo declared, "If we judge that Japan performed a provocative act again, we will respond strongly based on our domestic law," suggesting the use of weapons.[57]

- On 1 June, Japanese Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya expressed his decision to end talks about the dispute to Korean Minister of National Defense Jeong Kyeong-doo. While both defense ministers could not reach a conclusion together, both have pledged to make to efforts to improve relations between the two countries.[58]

Views and opinions

Toshio Tamogami, a retired general and ex-Chief of Staff of the JASDF, has given his views on his Twitter denying the offensiveness of aiming FC radar.[59] However, Toshiyuki Ito, a retired JMSDF admiral and ex-commandant of the Joint Staff College, rebutted Tamogami's view since the former had been retired for ten years and has no experience as a pilot.[60]

The Government of South Korea claimed this flight of P-1 was menacing and unfriendly to the warship of a neighbour country which was operating a rescue mission in the high seas. According to the Government of Korea, it is Japan, not Korea, if any, that acted ungentlemanly and menacingly to the neighbour country at the site and should apologize to the other.[61] However, Paul Giarra, a retired U.S. naval aviator and ex-senior Country Director for Japan in the Office of the ASD (ISA), pointed it out that there was absolutely no danger in the actions of the Japanese aircraft.[62]

Some Korean media were concerned about the friction between Seoul and Tokyo. On 7 January 2019, JoongAng Daily editorial argued that the two governments "should join forces to address the nuclear threats from North Korea and other urgent issues" and that "This emotional fighting does not help. Though what really happened at the moment has not yet been found, either side did not suffer substantial damage. Therefore, if Korean destroyer really aimed its FCR at the approaching airplane, our military authorities should apologize to Japan and wrap up the case. If the Japanese aircraft was really confused about the radar signal, it should apologize", and that "[i]t is time to take a deep breath and find a reasonable solution".[63]

While there is no international law regulating the altitude of military flights, Japan, the US Army, and NATO assert they follow the custom of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) to keep a distance of 150 meters from vessels under normal operations.[64]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2018 Japan–South Korea radar lock-on dispute. |

| Japanese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- 2013 Chinese Navy radar lock-on incident

External links

References

- http://www.mod.go.jp/e/press/release/2018/12/28z.html

- http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/international/japan/875429.html

- "Regarding the incident of an ROK naval vessel directing its fire-control radar at an MSDF patrol aircraft". Ministry of Defense. 21 December 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- "Japan releases footage of South Korean destroyer's radar lock-on on JMSDF patrol plane". Naval Today.com. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- Kajimoto, Tetsushi; Shin, Hyonhee (21 December 2018). "Japan accuses South Korea of 'extremely dangerous' radar lock on plane". Reuters. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- "Regarding the incident of an ROK naval vessel directing its fire-control radar at an MSDF patrol aircraft". Ministry of Defense. 22 December 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- "Japan shows video of alleged radar lock-on by SKorea warship". The Washington Post. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Forecast International (May 2013). Radar Forecast -MW08 (PDF) (Report).

- "[기획 한국군 무기 37] 해군 최초의 '방공구축함' 광개토대왕급". 31 May 2010.

- "한국-일본, '초계기 레이더 조준' 진실공방 격화". mbn.mk.co.kr (in Korean). 2 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "일본 레이더 공세에 軍 영상 맞불…대치 심화되나 [박수찬의 軍]". 일본 레이더 공세에 軍 영상 맞불…대치 심화되나 [박수찬의 軍] - 세상을 보는 눈, 글로벌 미디어 - 세계닷컴 - (in Korean). 5 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "광개토대왕함 사건은 일본의 기획도발?". news.donga.com (in Korean). 29 December 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- http://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez/393?chart=catch-chart&dimension=taxon&measure=tonnage&limit=10

- "Japan and South Korea's Unnecessary Squabble". thediplomat.com. 12 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "Regarding the incident of an ROK naval vessel directing its FCR at an MSDF patrol aircraft". Ministry of Defense. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Press Release: Regarding the incident of an ROK naval vessel directing its fire-control radar at an MSDF patrol aircraft". www.mod.go.jp. Japan Ministry of Defense. 21 December 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Japan accuses South Korea of 'extremely dangerous' radar lock on plane". Reuters. 21 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Types of Radars and its Characteristics" (PDF). Ministry of Defense (Japan). 28 December 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "South Korea denies warship locked FCR on Japanese plane". Independent. 25 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Korea's military rejects claim of targeting Japanese patrol aircraft". TheKoreaHerald. 23 December 2018.

- https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=025&aid=0002873587

- http://www.arirang.co.kr/News/News_View.asp?nseq=228851

- Panda, Ankit. "Japan, South Korea in Row Over Alleged Radar-Lock Incident". The Diplomat. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- "Press Release: Regarding the incident of an ROK naval vessel directing its fire-control radar at an MSDF patrol aircraft". www.mod.go.jp. Japan Ministry of Defense. 25 December 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "김종대 의원 "일본 극우층이 한국에 의식적으로 도발"" [Kim Jong-Dae, "Japan's LDP Party Convicts Korea"]. Chungcheong Today (in Kanuri). Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Ministry of Defense (27 December 2018). Announcement of Japan-Republic of Korea Working-Level Meeting (Report).

- Moonkwan Kim (29 December 2018). "Japan denied to reveal ESM recorder". Chosun ilbo (in Korean).

- Makino Yoshihiro (8 January 2019). "Republic of Korea refuses to provide data Evidence of radar irradiation". Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese).

- "S. Korea, Japan hold talks over radar strife". Yonhapnews.

- "Video release represents Abe's political intention". TheKoreaTimes. 30 December 2018.

- "Korea voices 'deep concern, regrets' about Japan's footage release amid radar spat". TheKoreaHerald. 28 December 2018.

- "South Korea demands apology from Japan for flight over navy warship". The Japan Times. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Top diplomats of S. Korea, Japan agree to pursue future-oriented ties amid radar spat". The Korea Herald. 3 January 2019.

- "Japan ready to exchange radar records with South Korea over maritime lock-on incident". JapanTimes. 9 January 2019.

- MoD (21 January 2019). MOD's final statement regarding the incident of an ROK naval vessel directing its fire-control radar at an MSDF patrol aircraft (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "Extended conflict between Japan and S.Korea". Financial news (in Korean). 16 January 2019.

- https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20190115082000503?input=1195m

- "S. Korea, Japan Fail to Narrow Differences on Radar Incident". world.kbs.co.kr. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Japan, S.Korea remain split over radar incident". NHK WORLD. NHK. 15 January 2019. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Makino Yoshihiro; Shinichi Fuziwara (15 January 2019). "Korea "Japan is rude and non-gentleman" conflict in negotiations over radar issues". Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese).

- Makino Yoshihiro (16 January 2019). "South Korea "If Japan fly low-flying we also" radar irradiation problem". Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese).

- "No resolution on the Radar spat". Yonhap news. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Extended radar spat...Japan: Disclosure of the sound file vs ROK: Japanese file is not provable". Herold Economics (in Korean). 21 January 2019.

- Statement of Korean MND regarding the incident about Japanese patrol plane (Report). Korean Ministry of National Defense. 22 January 2019.

- "Japan revealed RWR record...continuous dispute between Japan and S.Korea". Yonhap news (in Korean). 21 January 2019.

- "Entire story of the incident is on the log files". Kyunghyang Shinmun (in Korean). 21 January 2019.

- "Japan stopped negotiations. Korean MND expressed "Deep regret"". Seoul News (in Korean). 22 January 2019.

- https://www.defensenews.com/global/asia-pacific/2019/01/24/accusations-fly-between-south-korea-and-japan-over-threatening-aircraft-maneuvers-radar-targeting/

- Jiji Press. 23 January 2019 https://www.jiji.com/jc/article?k=2019012301335&g=soc. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Tong-Hyung, Kim (23 January 2019). "Seoul accuses Japanese patrol plane of threatening flight". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- https://news.v.daum.net/v/20190124170048215. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ""machines never lie"...The pictures show show the red circle on the plane". MBC News (in Korean). 24 January 2019.

- "S.Korean MND released images of JSDF's "threatening flight"". Sankei News (in Japanese). 24 January 2019.

- "MND requested more relible evidence from Japan". Yonhap News (in Korean). 25 January 2019.

- "Japan,"We are not going to reveal the data"". Yonhap News (in Korean). 25 January 2019.

- "The threatened is our patrol plane". TV Asahi (in Japanese). 25 January 2019.

- ""日 추가 도발 시 강력 대응"…軍, 무기 가동 검토". MBC news (in Korean). 27 January 2019.

- Tachikawa, Tomoyuki (1 June 2019). "Japan hints at ending talks about radar lock-on issue with S. Korea". Kyodo News. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Mr. Tamogami's controversial tweets and the safety of the FCR irradiated by South Korea". Nikkan Gendai (in Japanese). 27 December 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Former admiral refuted Mr. Tamogami's statement about the risk of Korean radar irradiation". Tokyo Sports (in Japanese). 7 January 2019.

- "Korea continues to demand Japan's apology over radar row". TheKoreaHerald. 2 January 2019.

- ""No dangerous movement on the Japanese side" US experts analyzed videos". TV Asahi (in Japanese). 5 January 2019. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019.

- "Time to end this spat with Japan (KOR)". JoongAngDaily. 7 January 2019.

- "韓国国防省、写真5枚を公開「威嚇飛行」 日本は否定". Asahi Press (in Japanese). 24 January 2019.