67th Guards Rifle Division

The 67th Guards Rifle Division was formed as an elite infantry division of the Red Army in January, 1943, based on the 1st formation of the 304th Rifle Division, and served in that role until after the end of the Great Patriotic War. It was officially redesignated in the 65th Army of Don Front, in recognition of that division's leading role in reducing the German 6th Army during Operation Ring, the destruction of the encircled German and Romanian forces at Stalingrad. During the following months it was substantially rebuilt while moving north during the spring of the year. The division put up a very strong defense in the Battle of Kursk, facing some of the main elements of Army Group South, and then attacked through the western Ukraine after the German defeat. Along with the rest of 6th Guards Army it moved further north to join 2nd Baltic and later 1st Baltic Front in the buildup to the summer offensive against Army Group Center, winning a battle honor and shortly after the Order of the Red Banner in the process. During the rest of 1944 it advanced through the Baltic states and ended the war near the Baltic Sea, helping to besiege Army Group Courland in 1945. The 67th Guards was disbanded in 1946.

| 67th Guards Rifle Division (January 21, 1943 – July, 1946) | |

|---|---|

Maj. Gen. A. I. Baksov, Hero of the Soviet Union | |

| Active | 1943–1946 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Division |

| Role | Infantry |

| Engagements | Operation Ring Battle of Kursk Belgorod-Kharkov Offensive Operation Battle of Nevel (1943) Operation Bagration Vitebsk-Orsha Offensive Baltic Offensive Operation Doppelkopf Šiauliai Offensive Memel Offensive Operation Courland Pocket |

| Decorations | |

| Battle honours | Vitebsk |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Maj. Gen. Serafim Pavlovich Merkulov Maj. Gen. Aleksei Ivanovich Baksov Maj. Gen. Yakov Filippovich Eremenko Col. Mikhail Petrovich Pugaev |

Formation

The 67th Guards was one of two Guards rifle divisions (the other being the 66th Guards) created prior to the German surrender during the Battle of Stalingrad. When formed, its order of battle was as follows:

- 196th Guards Rifle Regiment from 807th Rifle Regiment

- 199th Guards Rifle Regiment from 809th Rifle Regiment

- 201st Guards Rifle Regiment from 812nd Rifle Regiment

- 138th Guards Artillery Regiment from 404th Artillery Regiment

- 73rd Guards Antitank Battalion from 336th Antitank Battalion[1]

- 83rd Guards Antiaircraft Battery (until April 24, 1943)

- 68th Guards Reconnaissance Company

- 76th Guards Sapper Battalion

- 96th Guards Signal Battalion

- 71st Guards Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 66th Guards Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Company

- 69th Guards Motor Transport Company

- 70th Guards Field Bakery

- 72nd Guards Divisional Veterinary Hospital

- 799th Field Postal Station

- 892nd Field Office of the State Bank

Col. Serafim Pavlovich Merkulov, who had commanded the 304th prior to its redesignation, remained in command and was promoted to the rank of major general on January 27.

Operation Ring

The final stage of Operation Ring was scheduled to begin on January 22, but in the event began in earnest the day before with a strong reconnaissance-in-force by elements of the 24th, 65th and 21st Armies against the entire northwestern corner of 6th Army's defenses beginning just before 1000 hours. During the day this attack shattered the defenses of the VIII Army Corps' 113th, 76th and 44th Infantry Divisions in the 10 km-wide sector from just south of Novaya Nadezhda State Farm southward to Hill 134.4. The 76th was seriously damaged and Army Group Don reported in the evening that "the 44th ID seems to be crushed." Furthermore a gap 6 km wide had been carved into 6th Army's western front with no hope of being closed and Gumrak airfield was now within range of Soviet medium artillery. These successes were enough to secure Guards status for the 293rd and 304th Rifle Divisions by the end of the day.[2]

During January 25 the 65th Army pressed forward with the 27th and 67th Guards, 23rd and 233rd Rifle Divisions, converging on Aleksandrova and the western half of Gorodishche, capturing both towns as well as Razgulaevka Station. As they advanced these divisions pushed the 76th and 113rd Infantry back toward the Vishnevaia Balka and the western end of the Barrikady workers' settlement. The 67th Guards, 233rd and 24th Rifle Divisions then oriented their assault to the western edge of the Krasny Oktyabr village with the goal of linking up with the left wing of 62nd Army, specifically the 13th Guards and 284th Rifle Divisions. This was intended to chop 6th Army's pocket in two and succeeded just after dawn on January 26, catching the German defenders disorganized and demoralized by the previous day's combat. During the day the 67th Guards, with the 24th and 233rd, faced tough fighting against the remnants of the 76th Infantry, advancing 3–5 km. The division made the best progress, reaching and capturing Marker 73.6, less than 1000m from the western edge of the two factory villages.[3]

The southern German pocket, including Field Marshal F. Paulus, surrendered on January 31. The next day Don Front concentrated its artillery and airpower, along with the 62nd, 65th and 66th Armies against the roughly 50,000 men remaining in the northern pocket. The attack began at 0830 hours with a 90-minute artillery preparation with about 1,000 guns directly supporting 65th Army. The division gave support to the main attack by the 23rd and 24th Divisions across the Vishnevaia Balka which soon gained anywhere from 600-1,200m and resulted in the capture of up to 20,000 German soldiers and the through demoralization of the remainder. All but a few holdouts surrendered on February 2, and the 67th Guards and 214th Rifle Divisions drew the duty of clearing these from the factory district:

On 3 February... [t]he division of Biriukov concentrated on Verkhovnianskaia Street side by side with the men of Merkulov's division. They seized 600 prisoners that day. We, accompanied by Colonel Prozorov, went into the ruins... Approaching, we quietly peeped into a shallow shaft of concrete. On the bottom, wrapped up in unimaginable clothes, sat three German officers dealing cards... "Hands up." The Germans obediently stood up. The trump card flew into the snow. The game had ended.

Within days the division was transferred to 21st Army along with the 23rd Division, which became the 71st Guards Rifle Division on March 1.[4]

By the beginning of March, Don Front had become Central Front and at about the same time the 21st Army was re-designated as 6th Guards Army, joining Voronezh Front later that month. Along with nearly all of the Stalingrad divisions, the 67th Guards required extensive rebuilding during these months. During April it was assigned to 22nd Guards Rifle Corps and 6th Guards Army moved inside the Kursk salient, helping to fortify the south face of the bulge.[5][6] On June 23 General Merkulov handed his command over to Col. Aleksei Ivanovich Baksov, who would be promoted to major general on June 3, 1944.[7]

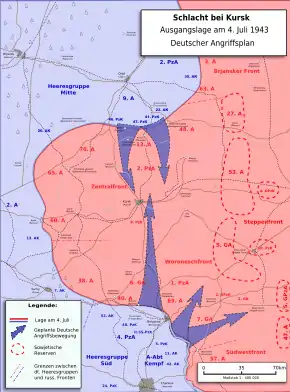

Battle of Kursk

As of July 1 the 22nd Guards Corps had the 67th and 71st Guards deployed in the first echelon and the 90th Guards Rifle Division in second echelon. The boundary between the 67th and 71st was secured with assets of the latter including a battery of its 151st Guards Artillery Regiment, a battery of regimental guns, two batteries of 82mm mortars, 11 antitank guns, 14 antitank rifles, three heavy and nine light machine guns. The 67th Guards disposed of somewhat fewer weapons. These were located southwest and south of the village of Cherkasskoe which was roughly the boundary between the divisions although held by the 67th. A minefield and an antitank ditch barred the approaches to its forward edge.[8] As a further part of the plan of defense Voronezh Front was committed to a counter-artillery preparation at such time it became clear that the German attack was imminent. The 67th Guards was to employ its 138th Guards Artillery Regiment, its regimental guns, and its 82mm and 120mm mortars on the approaches to Cherkasskoe. In the event this plan was preempted by forward detachments of 4th Panzer Army which attacked at 1610 hours on July 4, following bombing attacks and a 10-minute artillery preparation, with the goals of destroying the division's security outposts and seizing high ground for observation, but made only limited progress.[9]

Both divisions were struck at 0600 hours on the opening day of the German offensive by XXXXVIII Panzer Corps. This powerful formation included the 11th Panzer Division, Großdeutschland Panzer-Grenadier Division and the 10th Panzer Brigade, which was equipped with the first Panther tanks to enter service. The main German thrust came from the Gertsovka to Butovo area toward Korovino and Cherkasskoe with the 67th Guards facing an infantry regiment reinforced by 70 tanks and supported by 70 aircraft; this first effort was beaten off. Even before the attack began the German forces encountered serious problems due to minefields and other Soviet fixed defenses, as well as overcrowding on a very narrow attack sector. The Panthers became stuck in the minefields, blocking the tanks of Großdeutschland and forcing the infantry to go in without direct armor support. A marshy gully in front of the 196th Guards Rifle Regiment, which had been skilfully strengthened with a system of anti-tank obstacles, proved to be a difficult and time-consuming barrier. A second attack followed at 0710, this time with two infantry regiments and up to 100 tanks. Thanks to artillery fire from an antitank strongpoint which had been prepared near Cherkasskoe, as well as divisional and army artillery, this attack was also beaten back to its start line. Further attacks followed at 0800 and 1030 with no better results. Soviet observers recorded 25 tanks and up to 300 infantrymen blown up on the minefields in front of the village. By late in the morning the 27th Antitank Brigade arrived from 6th Guards Army reserve to help secure the boundary between the two Guards divisions.[10][11]

As the day wore on elements of the 3rd Panzer Division and Großdeutschland struck at the boundary between the two divisions, attempting to overrun the village strongpoints and also to outflank Cherkasskoe from the east. Successive bombing attacks cleared a path for their tanks and the infantry following; the armor advanced at low speed (no more than 5–10 km/h) with frequent stops while waiting for the infantry to come up. At noon an infantry regiment supported by 30 tanks attacked from Butovo toward heights 244.5 and 237.8, finally penetrating into the 67th Guards' defense. Despite this partial success the panzers became stuck between the two villages for the rest of the day, in heavy fighting, only establishing a tenuous hold on part of Cherkasskoe by midnight, a very poor showing for what was planned to be a major breakthrough of the Soviet defenses. The Soviet engineering technical service (TOS) had played an important role in assisting the defense, accounting for up to 200 German infantry and five tanks using delayed-action mines and booby traps near height 244.5 and on the approaches to Cherkasskoe.[12][13]

During this fighting a battalion of the 196th Guards Regiment defending an antitank strongpoint was ordered by Colonel Baksov to fall back to an alternate defensive line to the north. A platoon under command of Jr. Lt. Alekov was tasked with covering the battalion's withdrawal; Alekov reportedly motivated his 15 men with the shout, "The Guard may die, but does not retreat!" Covered by the fire of this platoon the battalion was able to fall back in an organized fashion and halt any further German advance, although Alekov and all members of his platoon were killed. By day's end the day the two divisions occupied a line from Bubny to Nova-Ivanovka to Yarki to Trirechnoe.[14]

On July 6 the 67th Guards Rifle continued in savage combat with the XXXXVIII Panzer Corps. The German attack began at 1000 hours with an artillery and air preparation; the plan was to launch two concentric attacks along the Oboyan axis with one, involving the 11th Panzer, Großdeutschland, and the 332nd Infantry Division, to encircle Cherkasskoe before pressing on toward Pokrovka.[15] Masses of heavy armor, including Tiger tanks, pushed against the division's positions without making a breakthrough. For its part, the division employed tank-hunting dogs very successfully:

Lieutenant Lisitin's platoon, which was operating in the sector of the 67th Guards Rifle Division's 196th Guards Rifle Regiment, blew up 12 tanks with its dogs, for which 16 dogs were expended (4 dogs were killed as they approached the enemy tanks).[16]

When German armor arrived at Dmitrievka the combat became very intense as individual antitank men, armed with Molotov cocktails and grenades, were sent forth to repulse the attack. The chief of the 199th Guards Regiment's chemical service, Cpt. Batanov, led his group of tank destroyers until the panzers advanced within 15-20m, at which point their projectiles halted or destroyed up to 12 tanks.[17] In spite of these successes, the division's line was overrun by Großdeutschland and the 11th Panzer Division, and 6th Guards Army ordered the division to fall back to a further line in the Syrtsevo to Dubrova area. The situation was made worse by lack of cooperation and communications between 22nd Guards Corps and the 1st Tank Army, which was intended to be a backstop to 6th Guards.[18] By nightfall the division was partly encircled and had to slip out through German lines, with substantial losses. On the morning of July 7 it was moved into the Army reserve along with the 51st and 52nd Guards Rifle Divisions of the neighboring 23rd Guards Rifle Corps where it began putting itself in order in the Berezovka area. Overnight the division occupied defensive positions along the line of the southern outskirts of Verkhopene to Shchenyachii woods to Stanovaya woods. The following day the 67th and 51st Guards cooperated with elements of the 3rd Mechanized and 6th Tank Corps in blocking any German advance along the direct paved road to Oboyan. In order to create more favorable conditions for a renewed attack on July 9 a German infantry regiment supported by 60 tanks attacked the division at 0200 hours along the southern outskirts of the strongpoint of Verkhopene and pushed them back to the north. The main assault unfolded at 0900 following a massive airstrike. On the Verkhopene to Stanovaya woods sector up to 200 panzers struck units of the 3rd Mechanized and 67th Guards defending the southern slopes of height 242, 3.5 km east of the village. The first attack was beaten off by the fire of antitank artillery and dug-in tanks with significant losses and a further attempt at 1130 hours fared similarly. The German forces now undertook to outflank Verkhopene to the east, heading for Kalinovka; at the same time German infantry renewed the attack from the village's southern outskirts and, following fierce street fighting, reached the northeastern outskirts. By 1300 the division had fallen back to a line from the southern outskirts of Kalinovka to height 251.4 and by day's end had suffered considerable casualties and had retreated farther north to the Kalinovka to Vladimirovka area to regroup. The German breakthrough attempt in the area had been stymied by the combined Soviet forces, including the 309th Rifle Division which was now covering the 67th Guards and 3rd Mechanized.[19]

Throughout July 10 the XXXXVIII Panzer Corps continued to attack the division and the 10th Tank and 3rd Mechanized Corps, attempting to advance west of the Oboyan road with up to 100 tanks, but by the onset of darkness the defenders continued to hold their positions. Overnight these were reinforced by elements of the 40th Army. At about this time the division was reassigned to the 23rd Guards Rifle Corps, which also contained the 309th and 204th Rifle Divisions. Overnight on July 10/11 Voronezh Front made plans to go over to the counteroffensive with the 23rd Guards Corps attacking from the line of Kalinovka to height 244.8 in the general direction of Krasnaya Dubrava and Pokrovka on the morning of July 12. At 0400 hours the Corps occupied its jumping-off positions. While the major tank battle at Prokhorovka took place the Corps, along with units of the 3rd Mechanized and 31st Tank Corps, attacked from 0830 until 1700 hours; the 204th and 309th Divisions gained some ground but the 67th Guards did not. Further efforts on July 14 made no progress and on the morning of the 15th the 6th Guards Army went over to the defense. The 67th division played little role in the rest of the battle, and once again had to be substantially rebuilt.[20][21] By the beginning of August it had returned to 22nd Guards Corps with the 71st and 90th Guards.[22]

Belgorod-Kharkov Offensive

On July 24 the STAVKA announced on Moscow radio that the German forces had been forced back to their lines of July 5. While the Belgorod-Kharkov Offensive did not officially start until August 3, in fact fighting continued through these ten days. The new offensive was led by 5th Guards Army with 6th Guards, three other field armies and two tank armies in support. Belgorod was liberated on August 5. Two days later the offensive began to focus in the area of Bogodukhov and 6th Guards was brought up to reinforce 1st Tank Army. By August 11 the Army was advancing on Poltava and in a directive from the Front commander on the afternoon of August 13 the 67th and 71st Guards were ordered to reach a line from Berezovka to Kolomak and secure it to prevent any German breakthrough along this sector. However a counterthrust on August 15 by 3rd SS Panzergrenadier Division Totenkopf flanked the Army and drove it off to the north, reaching the line of the Merla River. The German forces went over to the defense on this axis on August 17.[23][24]

Redeployment to the North

On September 21 the 138th Guards Artillery Regiment was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for "the exemplary performance of command assignments in battles, and display of valor and courage."[25] At about the same time the 6th Guards Army was withdrawn to the Reserve of the Supreme High Command and began to redeploy to the north-central sector of the front, arriving in 2nd Baltic Front in October; the 67th Guards remained in 22nd Guards Corps.[26]

Battle of Nevel

The Army soon entered the salient west of Nevel that had been created by the 3rd and 4th Shock Armies in early October and on November 10 went into action in the lake region northeast of the town. It went over to the attack in the narrow sector between Lake Bolshoi Ivan and Lake Nevel against German defenses at Karataia manned by the 56th and 69th Infantry Divisions of 16th Army's I Army Corps. 22nd Guards Corps was deployed on the right with the 67th Guards in second echelon. The assault was supported by two tank brigades but made only painful progress, as indicated in the history of the 71st Guards:

The division's first echelon regiments advanced 600-700 meters on the first day of combat and approached right up to the forward edge of the enemy's defense... Occupying dominating heights, the enemy had created powerful and well-camouflaged defensive positions. The division artillery was not able to destroy or even suppress the enemy's firing systems. The terrain, which was broken up by ravines and swamps, did not permit the full use of tanks in the attack and the foul weather hindered the deployment of aircraft. The attack by the division and the other formations of 6th Guards Army did not produce the expected results at that time.

The Army went over to the defense on November 15. By the end of the month the 67th and 71st Guards were reassigned to the 96th Rifle Corps, still in 6th Guards Army.[27]

On December 8 the German 122nd Infantry Division punched a small penetration through the defenses of the 71st Guards which required intervention by the 23rd Guards Corps. This helped convince the Soviet command to finally eliminate the German salient from Novosokolniki south nearly to Nevel. In late December the Front began a new offensive in the direction of Idritsa and Pustoshka, while 1st Baltic Front continued attacking south towards Vitebsk. 2nd Baltic was caught off-guard when 16th Army began evacuating the salient on December 29. The 67th Guards was now in the 97th Rifle Corps directly north of Nevel and took part in the pursuit of the retreating German forces, along with the 51st and 71st Guards and backed by two tank brigades and a regiment. While the history of 6th Guards Army states that I Army Corps was driven back in heavy fighting it appears from German records and Soviet casualty figures that most of the combat occurred when the new German defense line at the base of the salient was reached on January 6, 1944. Within a month the Red Army offensives at Leningrad and Novgorod forced 16th Army to wheel its defenses westward to near Pskov.[28]

Operation Bagration

During January the division was transferred to the 12th Guards Rifle Corps before returning to the 23rd Guards Corps in February when the 6th Guards Army was transferred to the 1st Baltic Front.[29] The division would remain in this Corps for the duration of the war.

In the planning for Operation Bagration, the Corps was given an assault role, compressed into a front of just 10 km, working with the two assault corps of the adjacent 43rd Army. 6th Guards Army had been moved in secrecy into the line north of the German-held Vitebsk salient over three nights previous to the attack.[30] It deployed the 22nd and 23rd Guards Corps in the first echelon with the 103rd and 2nd Guards Rifle Corps in the second. The 23rd Guards was to break through the German defense between Byvalino and Novaya Igumenshchina and then drive headlong in the direction of Dobrino, cut the rail line and highway between Vitebsk and Polotsk, and capture a line from Verbali to Gubitsa. Subsequently it was to attack toward Zheludova and Pyatigorsk and clear a passage for the commitment of the 1st Tank Corps.[31] The Soviet assault on June 22 began at dawn with a very heavy artillery barrage against the positions of the German 252nd Infantry Division and Corps Detachment D. By noon the assault battalions of the division had broken through the second German defense line and reached the Obol River. The following armored group crossed the river and advanced a total of 7 km by evening. On the second day an additional advance of 16 km was made, and during the following night Corps Detachment D collapsed. By the evening of the 24th, the division crossed the Dvina River north of Beshenkovichi and held a 50 km front along the river; the gap between 6th Guards Army attacking from the north and 39th Army from the south was narrowed to just 10 km. On the 25th the other two divisions of 23rd Guards Rifle Corps used the 67th Guards Rifle's bridgehead to develop the offensive westward, and late that day, farther to the east, the pincers closed on the Vitebsk salient, trapping what remained of five German divisions.[32] In recognition of its achievements in this offensive, the 67th Guards was awarded its honorific:

"VITEBSK... 67th Guards Rifle Division (Maj. Gen. Baksov, Aleksei Ivanovich)... By order of the Supreme High Command of 26 June 1944, and a commendation in Moscow, the troops who participated in the liberation of Vitebsk are given a salute of 20 salvoes by 224 guns."[33]

On July 22 the commander of the 201st Guards Rifle Regiment, Lt. Col. Georgi Aleksandrovich Inozemtsev, was named as a Hero of the Soviet Union. Born at Bataysk he had been a historian and civil servant, as well as a Red Army reservist, before the war. He took command of the Regiment on September 16, 1943 after having served as the chief of staff of the 199th Guards Regiment at Kursk. Conducting a reconnaissance-in-force on the evening of June 22 he led the Regiment into the German defense line and captured the village of Ratkovo. The next day the Regiment cut the Vitebsk - Polotsk railway line and crossed the Dvina River, during which Inozemtsev was wounded, but did not leave his command. After fighting off several German counterattacks the 201st secured the crossing of the rest of the 67th Guards. During the day the Regiment claimed over 700 enemy soldiers and officers killed or wounded, and captured 37 prisoners. Inozemtsev went on to command the 71st Guards Division in early 1945 and published a number of articles and books on the history and prehistory of the Rostov region before his death in 1957.[34]

Baltic Offensives

The destruction of German LIII Army Corps at Vitebsk helped to open a large gap between their Army Groups Center and North. By June 26 the 67th Guards was located near Obol, north of the Dvina and about 35 km southeast of Polotsk.[35] On June 30 the 23rd Guards Corps, led by 1st Tank Corps, was ordered into the gap, bypassing south of the remaining German positions at Polotsk. That city was liberated on July 4 and on July 23 the division would be awarded the Order of the Red Banner for its part in this victory.[36]

By the beginning of August the 6th Guards Army had advanced deep into the "Baltic Gap" and had crossed the border into Lithuania and the division had reached the area of Rokiškis.[37] On August 8 General Baksov was given command of the 2nd Guards Rifle Corps and was replaced in command of the division by Maj. Gen. Yakov Filippovich Eremenko; Baksov would go on to be promoted to the rank of colonel general in 1963. At the start of the German Operation Doppelkopf in mid-August the division was located north of Biržai and after helping to fight off the counteroffensive advanced on Šiauliai.[38] On October 31 all three rifle regiments of the division would be decorated for their roles in the fighting for this city, with the 196th winning the Order of the Red Banner, the 199th receiving the Order of Suvorov, 3rd Degree, and the 201st being presented the Order of Kutuzov, 3rd Degree.[39]

Over the following months the 1st Baltic Front pushed through to the Baltic coast, and what remained of Army Group North was confined to the Courland Pocket. On January 12, 1945 General Eremenko was succeeded in command by Hero of the Soviet Union Col. Lev Illarionovich Puzanov, but this officer was in turn replaced a week later by Col. Mikhail Petrovich Pugaev, who would remain in command for the duration. The division remained in this region for the duration as part of the confining forces; in April, 1945, it was reassigned, along with the rest of its corps, to 67th Army.[40]

Postwar

At the war's end the division's men and women shared the full title of 67th Guards Rifle, Vitebsk, Order of the Red Banner Division. (Russian: 67-я гвардейская стрелковая Витебская Краснознамённая дивизия.) After the war, the division was based at Liepāja in western Latvia.[41] In September it came under command of Maj. Gen. Vladimir Arkadievich Rodionov who held this position for the remainder of the division's existence. It was disbanded at Liepāja in September, 1946.[42]

References

Citations

- Charles C. Sharp, "Red Guards", Soviet Guards Rifle and Airborne Units 1941 to 1945, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. IV, 1995, p. 71

- David M. Glantz, Endgame at Stalingrad, Book Two, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2014, pp. 506-09

- Glantz, Endgame at Stalingrad, Book Two, pp. 525-26, 530, 536

- Glantz, Endgame at Stalingrad, Book Two, pp. 564-67, 575

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 63, 87, 111

- Sharp, "Red Guards", p. 72

- http://www.generals.dk states that Merkulov left command of the division on February 2: http://generals.dk/general/Merkulov/Serafim_Petrovich/Soviet_Union.html. Zamulin gives the date of Baksov's command as June 30; Zamulin, The Battle of Kursk - Controversial and Neglected Aspects, p. 231

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., Book 1, ch. 1, 2

- Valeriy Zamulin, The Battle of Kursk - Controversial and Neglected Aspects, ed. & trans. S. Britton, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2017, pp. 207, 210

- Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, ed. & trans. S. Britton, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2011, p. 103

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., Book 1, ch. 3

- Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 103-04

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., Book 1, ch. 3

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., Book 1, ch. 3. This source does not state who recorded Alekov's words.

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., Book 1, ch. 3.

- Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, p. 117. This source mistakenly gives the number of the regiment as the "169th".

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., Book 1, ch. 3.

- Zamulin, The Battle of Kursk - Controversial and Neglected Aspects, p. 238

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., Book 1, ch. 3.

- Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 123, 427

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., Book 1, ch. 3.

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 193

- Roman Töppel, Kursk 1943: The Greatest Battle of the Second World War, Helion & Co., Ltd., Warwick, UK, 2018, Kindle ed., ch. 2, sect. Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev

- Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., Book 2, ch. 2

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 200.

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 263, 273

- Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2016, pp. 148-51

- Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 235-39, 304-06, 691

- Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 38, 68

- Walter S. Dunn, Jr. Soviet Blitzkrieg, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, US, 2008, pp. 97-98

- Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., vol. 1, ch. 3

- Dunn, Jr., Soviet Blitzkrieg, pp. 95-98, 102-07

- http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-1.html. Retrieved October 6, 2017.

- http://www.warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=10638. In Russian; English translation available. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- The Gamers, Inc., Baltic Gap, Multi-Man Publishing, Inc., Millersville, MD, 2009, p. 9

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 398.

- The Gamers, Inc., Baltic Gap, p. 22

- The Gamers, Inc., Baltic Gap, pp. 27, 28

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, pp. 533-34.

- Sharp, "Red Guards", p. 72

- Feskov et al 2013, p. 441

- Feskov et al 2013, p. 147

Bibliography

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967a). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть I. 1920 - 1944 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part I. 1920–1944] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow.

- Feskov, V.I.; Golikov, V.I.; Kalashnikov, K.A.; Slugin, S.A. (2013). Вооруженные силы СССР после Второй Мировой войны: от Красной Армии к Советской [The Armed Forces of the USSR after World War II: From the Red Army to the Soviet: Part 1 Land Forces] (in Russian). Tomsk: Scientific and Technical Literature Publishing. ISBN 9785895035306.

- Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. pp. 186–87

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941 – 1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. p. 322

External links

- Serafim Petrovich Merkulov

- Aleksei Ivanovich Baksov

- Yakov Filippovich Eremenko

- HSU Serafim Petrovich Merkulov

- HSU Aleksei Ivanovich Baksov

- HSU Georgi Aleksandrovich Inozemtsev

- HSU Lev Illarionovich Puzanov

- HSU Vladimir Arkadievich Rodionov

- Brief combat path of the 67th Guards. In Russian typescript.

- Combat path of the 67th Guards. In Russian manuscript.