9K38 Igla

The 9K38 Igla (Russian: Игла́, "needle", NATO reporting name SA-18 Grouse) is a Russian/Soviet man-portable infrared homing surface-to-air missile (SAM) system. A simplified, earlier version is known as the 9K310 Igla-1, or SA-16 Gimlet, and the latest variant is the 9K338 Igla-S (SA-24 Grinch).

| Igla | |

|---|---|

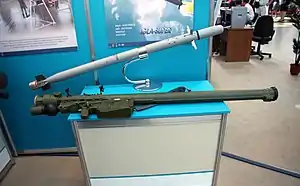

9K338 Igla-S (SA-24) missile and launch tube. | |

| Type | Man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS) |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1981 - Present |

| Used by | See Operators |

| Wars | Gulf War Cenepa War Yugoslav Wars Bosnian War Iraq War Second Chechen War Somali Civil War First Libyan Civil War Syrian Civil War,[1] Ukrainian Crisis (War in Donbass) Insurgency in Egypt (2013–present) (Sinai insurgency) Kurdish-Turkish conflict (2015-present) 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | KB Mashinostroyeniya – Developer of the system |

| Produced | 1981 - Present |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | Missile weight: 10.8 kg (24 lb) Full system: 17.9 kg (39 lb) |

| Length | 1.574 m (5.16 ft) |

| Diameter | 72 mm |

| Warhead | 1.17 kg (2.6 lb) with 390 g (14 oz) explosive |

Detonation mechanism | Contact and grazing fuze |

| Engine | Solid fuel rocket motor |

Operational range | 5.0 km (3.1 mi) - Igla-1 5.2 km (3.2 mi) - Igla 6.0 km (3.7 mi) - Igla-S |

| Flight ceiling | 3.5 km (11,000 ft) |

| Maximum speed | 570m/s[2] (peak), about Mach 1.9 |

Guidance system | Dual waveband infra-red (S-version)[3] |

The Igla-1 entered service in 1981, the Igla in 1983, and the Igla-S in 2004.[4] The Igla is being supplemented by the 9K333 Verba since 2014.[5]

History

The development of the Igla short-range man-portable air defense system (MANPADS) began in the Kolomna OKB in 1972. Contrary to what is commonly reported, the Igla is not an improved version of the earlier Strela family (Strela-2 and Strela-3), but an all-new project. The main goals were to create a missile with better resistance to countermeasures and wider engagement envelope than the earlier Strela series MANPADS systems.

Technical difficulties in the development quickly made it obvious that the development would take far longer than anticipated, however, and in 1978 the program split in two: while the development of the full-capability Igla would continue, a simplified version (Igla-1) with a simpler IR seeker based on that of the earlier Strela-3 would be developed to enter service earlier than the full-capability version could be finished.

Igla-1

The 9K310 Igla-1 system and its 9M313 missile were accepted into service in the Soviet army on 11 March 1981. The main differences from the Strela-3 included an optional Identification Friend or Foe system to prevent firing on friendly aircraft, an automatic lead and super elevation to simplify shooting and reduce minimum firing range, a slightly larger rocket, reduced drag and better guidance system extend maximum range and improve performance against fast and maneuverable targets, an improved lethality on target achieved by a combination of delayed impact fuzing, terminal maneuver to hit the fuselage rather than jet nozzle, an additional charge to set off the remaining rocket fuel (if any) on impact, an improved resistance to infrared countermeasures (both decoy flares and ALQ-144 series jamming emitters), and slightly improved seeker sensitivity.

The seeker has two detectors – a cooled MWIR InSb detector for detection of the target and uncooled PbS SWIR detector for detection of IR decoys (flares). The built-in logic determines whether the detected object is a target or a decoy. The latest version (Igla-S) is reported to have additional detectors around the main seeker to provide further resistance against pulsed IRCM devices commonly used on helicopters.

The 9M313 missile features an aerospike mounted on a tripod (Igla's 9M39 missile has aerospike attached directly to the seeker dome), which reduces a shock wave, thus providing less dome heating and greater range. The name Igla is derived from these devices.

Like many other MANPADS, Igla-1 and Igla feature so-called rolling airframe missiles. These missiles roll in flight (900 – 1200 rpm) so steering the missile requires just a single pair of control surfaces, unlike roll-stabilized missiles, which require separate control surfaces for pitch and yaw. Both 9M313 and 9M39 missiles contain a gas generator, which drives a small gas turbine to provide electrical power, and the pistons, which move the canards used to steer the missile in a bang-bang mode. In addition to that, two exhaust tubes of the gas generator are placed perpendicular to the steering canards to provide maneuverability immediately after launch when the missile airspeed is too low for canards to be effective. Later versions of Igla are reported to use proportional control to drive the canards, which enables greater precision and less oscillation of the flight path.

According to the manufacturer, South African tests have shown the Igla's superiority over the contemporary (1982 service entry) but smaller and lighter American FIM-92A Stinger missile. According to Kolomna OKB, the Igla-1 has a Pk (probability of kill) of 0.30 to 0.48 against unprotected targets which is reduced to 0.24 in the presence of decoy flares and jamming.[6] In another report, the manufacturer claimed a Pk of 0.59 against an approaching and 0.44 against receding F-4 Phantom II fighter not employing infrared countermeasures or evasive maneuvers.

Igla

.jpg.webp)

The full-capability 9K38 Igla with its 9M39 missile was finally accepted into service in the Soviet Army in 1983. The main improvements over the Igla-1 included much improved resistance against flares and jamming, a more sensitive seeker, expanding forward-hemisphere engagement capability to include straight-approaching fighters (all-aspect capability) under favourable circumstances, a slightly longer range, a higher-impulse, shorter-burning rocket with higher peak velocity (but approximately same time of flight to maximum range).

The naval variant of 9K38 Igla has the NATO reporting name SA-N-10 Grouse.

The Igla–1M missile consists of a Ground Power Supply Source (GPSS), Launching Tube, Launching Mechanism & Missile (9M313–1).

There is also a two-barrel 9K38 missile launcher called Dzhigit.[7][8]

9K338 Igla-S (SA-24 Grinch)

The newest variant, which is a substantially improved variant with longer range, more sensitive seeker, improved resistance to latest countermeasures, and a heavier warhead. Manufacturer reports hit probability of 0.8–0.9.[9] State tests were completed in December 2001 and the system entered service in 2002. Series produced by the Degtyarev plant since 1 December 2004.[3]

Replacement

Since 2014 the Igla is being replaced in Russian service by the new 9K333 Verba (Willow) MANPADS.[5] The Verba's primary feature is its multispectral optical seeker, using three sensors as opposed to the Igla-S' two. Cross-checking sensors against one another better discriminates between relevant targets and decoys, and decreases the chance of disruption from countermeasures, including lasers that attempt to blind missiles.[10]

Operational history

Operation Trishul Shakti (1992)

28 July – 2 August 1992: Indian Army launched Operation Trishul Shakti to protect the Bahadur post in Chulung when it was attacked by a large Pakistani assault team. On 1 August 1992, Pakistani helicopters were attacked by an Indian Igla missile and Brig. Masood Navid Anwari (PA 10117) then Force Commander Northern Areas and other accompanying troops were killed. This led to a loss of momentum on the Pakistani side and the assault stalled.[11]

Desert Storm (1991)

The first combat use of the Igla-1E was during the Gulf War Operation GRANBY. On 17 January 1991, a Panavia Tornado bomber of the Royal Air Force was shot down by an Iraqi MANPADS that may have been an Igla-1E (or Strela-3) after an unsuccessful bombing mission. The crew, Flt Lts J G Peters and A J Nichol, were both captured and held as prisoners of war (POWs) until the cessation of hostilities.[12][13]

In addition, an Igla-1E shot down an American F-16 on 27 February 1991. The pilot was captured.[14]

It is uncertain if an AC-130H lost was hit by a 'Strela' missile or a more recent Igla since Iraq had SA-7, SA-14 and SA-16 missiles at the time, according to the SIPRI database.

From 2003

During the Iraq War, American and coalition forces suffered a number of helicopter losses. A third of them, around 40 aircraft were due to hostile fire, including losses to small arms fire, Anti Aircraft guns, Rocket-propelled grenades and MANPADS; any kind of combat helicopter was shot down from small observation helicopters to armoured Apache gunships. Among the losses to MANPADS, some were reported as losses to older Strela-2 (SA-7) or Strela-3 (SA-14) while others were due to more modern Igla-1E (SA-16) missiles.

Rwanda

Igla-1E missiles were used in the 1994 shoot down of a Rwandan government flight, killing the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi and sparking the Rwandan genocide.[15]

Cenepa War

During the Cenepa War between Ecuador and Peru, both the Ecuadorian Army and the Peruvian Army (which had 90 functioning firing units) utilized Igla-1E missiles against aircraft and helicopters.

A Peruvian Air Force Mi-25 attack helicopter was shot down on 7 February 1995 around Base del Sur, killing the 3 crewmen, while an Ecuadorian Air Force A-37 Dragonfly was hit but managed to land on 11 February. Hits on additional Ecuadorian aircraft were claimed but could not be confirmed.[16]

Bosnia

During Operation Deliberate Force, on 30 August 1995; a French Mirage 2000D was shot down over Pale by an Igla fired by air defence units of the Army of Republika Srpska.[17] The pilots, Lt. Jose-Manuel Souvignet (pilot) and Capt. Frederic Chiffot (back-seater), were captured and freed in December 1995.[18]

Chechnya

The 2002 Khankala Mi-26 crash occurred on 19 August 2002 when a team of Chechen separatists brought down a Russian Mil Mi-26 helicopter in a minefield with an Igla; this resulted in the death of 127 Russian soldiers in the greatest loss of life in the history of helicopter aviation. It was also the most deadly aviation disaster ever suffered by the Russian armed forces,[19] as well as their worst loss of life in a single day since 1999.[20]

Egypt

On 26 January 2014, the militant group Ansar Bait al-Maqdis shot down an Egyptian Mi-17 over the northern Sinai peninsula using a suspected Igla-1E or Igla. How the group came to obtain the weapon is currently unknown.[21]

Libya

During the 2011 military intervention in Libya, Libyan loyalist forces engaged coalition aircraft with a certain number of Igla-S. Three Igla-S were fired against British Apache attack helicopters of the 656 Squadron Army Air Corps operating from the amphibious assault ship HMS Ocean. According to the squadron commander at the time, they were all dodged by insistent use of decoy flares by the gunships who in exchange successfully engaged the shooters.[22][23]

On 23 March 2015, a Libya Dawn-operated MiG-23UB was shot down with an Igla-S (reportedly a truck-mounted Strelets variant) while bombing Al Watiya airbase (near Zintan), controlled by forces from the internationally recognized House of Representatives. Both pilots were killed.[24][25]

Plot against Air Force One

On 12 August 2003, as a result of a sting operation arranged as a result of cooperation between the American, British and Russian intelligence agencies, Hemant Lakhani, a British national, was intercepted attempting to bring what he had thought was an older-generation Igla into the United States. He is said to have intended the missile to be used in an attack on Air Force One, the American presidential plane, or on a commercial US airliner, and is understood to have planned to buy 50 more of these weapons.

After the Federalnaya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti (FSB) detected the dealer in Russia, he was approached by US undercover agents posing as terrorists wanting to shoot down a commercial plane. He was then provided with an inert Igla by undercover Russian agents, and arrested in Newark, New Jersey, when making the delivery to the undercover US agent. An Indian citizen residing in Malaysia, Moinuddeen Ahmed Hameed and an American Yehuda Abraham who allegedly provided money to buy the missile were also arrested.[26] Yehuda Abraham is President and CEO of Ambuy Gem Corp.[27][28] Lakhani was convicted by jury in April 2005, and was sentenced to 47 years in prison.[29]

Syria

Video has surfaced showing rebels using an Igla-1E on a Syrian government helicopter. Such weapons were believed to have been looted from a Syrian army base in Aleppo in February 2013. In 2014, a member of the rebel group Harakat Hazm was filmed aiming an Igla-1E into the air on the same day that the group was filmed operating BGM-71 TOW missiles.[30] Whether these weapons were raided from regime stockpiles or supplied via overseas is unknown. However, Russia reportly denied Syrian demand for Iglas in 2005 and 2007, fearing these weapons to be used by Hezbollah.[31]

Ukraine

On 14 June 2014, rebel forces near Luhansk International Airport in Eastern Ukraine shot down an IL-76 of the Ukrainian Airforce probably using an Igla MANPADS, killing all 49 Ukrainian service personnel on board.[32]

Nagorno Karabakh

On 12 November 2014, Azerbaijani forces shot down an Armenian Army Mi-24 of a formation of two which were flying near the Azerbaijani border. All three on board died when the helicopter crashed while flying at low altitude and was hit by an Igla-S MANPADS fired by Azerbaijani soldiers.[33][34][35]

Turkey

On 13 May 2016, PKK militants shot down a Turkish Army Bell AH-1W SuperCobra attack helicopter using 9K38 Igla (SA-18 Grouse) version of this missile system. The missile severed the tail section from the rest of the helicopter, causing it to fragment in midair and crash, killing the two pilots on board. The Turkish government first claimed that it fell due to technical failure before it became clear that it was shot down. The PKK later released video footage of the rocket being fired and striking the helicopter.[36]

Variants

.jpg.webp)

- Igla-1 is a simplified early production version. It is known in the West as SA-16 Gimlet. It had a maximum range of 5 000 m and could reach targets at a maximum altitude of 2 500 m.

- Igla-1E is an export version. It has been exported to a number of countries.

- Igla (SA-18 Grouse) is a standard production version. It was adopted in 1983. Currently it is in service with more than 30 countries, including Russia.

- Igla-D, version developed specially for the Soviet airborne troops. Its launch tube can be disassembled and carried in two separate sections in order to reduce dimensions.

- Igla-M is a naval version for the naval boats. Its Western designation is SA-N-10 Grouse.

- Igla-V is an air-to-air version, used on helicopters.

- Igla-N is a version with much larger and more powerful warhead.

- Igla-S, sometimes referred as Igla-Super. It is an improved variant in the Igla, which entered service with Russian Army in 2004. It is known in the West as SA-24 Grinch.

Comparison chart to other MANPADS

| 9K34 Strela-3 /SA-14 | 9K38 Igla /SA-18 | 9K310 Igla-1 /SA-16 | 9K338 Igla-S /SA-24 | FIM-92C Stinger | Grom [37] |

Starstreak [38][39] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service entry | 1974 | 1983 | 1981 | 2004 | 1987 | 1995 | 1997 |

| Weight, full system, ready to shoot kg (lb) |

16.0 (35.3) | 17.9 (39) | 17.9 (39) | 19 (42) | 14.3 (32) | 16.5 (36) | 20.00 (44.09) |

| Weight, missile kg (lb) |

10.3 (23) | 10.8 (24) | 10.8 (24) | 11.7 (26) | 10.1 (22) | 10.5 (23) | 14.00 (30.86)[38] |

| Weight, warhead kg (lb) g (oz) |

1.17 (2.6), 390 (14) HMX |

1.17 (2.6), 390 (14) HMX |

1.17 (2.6), 390 (14) HMX |

2.5 (5.5), 585 (20.6) HMX |

2.25 (1.02) HTA-3[40] | 1.27 (2.8) | 3x 0.90 (2.0) tungsten alloy darts, 3x 450 (16) PBX-98 |

| Warhead type | Directed-energy blast fragmentation |

Directed-energy blast fragmentation |

Directed-energy blast fragmentation |

Directed-energy blast fragmentation |

Annular blast fragmentation | Blast fragmentation | Blast fragmentation |

| Fuze type | Impact and grazing fuze. | Delayed impact, magnetic and grazing. |

Delayed impact, magnetic and grazing. |

Delayed impact, magnetic and grazing. |

Delayed impact. | Impact. | Delayed impact, armour-piercing. |

| Flight speed, average / peak m/s (mph) |

470 (1,100) sustained |

600 (1,300) / 800 (1,800) |

570 (1,300) sustained (in + temperature) |

? | 700 (1,600) / 750 (1,700) |

580 (1,300) / 650 (1,500) |

1,190 (2,700) / 1,360 (3,000)[41] |

| Maximum range m (ft) |

4,100 (13,500) | 5,200 (17,100) | 5,000 (16,000) | 6,000 (20,000) | 4,500 (14,800) | 5,500 (18,000) | 7,000 (23,000)+ |

| Maximum target speed, receding m/s (mph) |

260 (580) | 360 (810) | 360 (810) | 400 (890) | ? | 320 (720) | ? |

| Maximum target speed, approaching m/s (mph) |

310 (690) | 320 (720) | 320 (720) | 320 (720) | ? | 360 (810) | ? |

| Seeker head type | Nitrogen-cooled, lead sulfide (PbS) |

Nitrogen-cooled, Indium antimonide (InSb) and uncooled lead sulfide (PbS) |

Nitrogen-cooled, Indium antimonide (InSb) |

? | Argon-cooled, Indium antimonide (InSb) |

? | SACLOS and SALH |

| Seeker scanning | FM-modulated | FM-modulated | FM-modulated | FM-modulated | FM-modulated | FM-modulated | Low intensity modulated-laser-homing darts |

| Seeker notes | Aerospike to reduce supersonic wave drag |

Tripod-mounted nosecone to reduce supersonic wave drag |

Low laser beam energy levels ensuring no warning to target |

Operators

Igla and Igla-1 SAMs have been exported from the former Soviet Union to over 30 countries, including Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cuba, East Germany, Egypt, Ecuador, Eritrea, Finland, Hungary, India, Iran, Iraq, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, North Korea, North Macedonia, Peru, Poland, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Vietnam and Zimbabwe. Several guerrilla and terrorist organizations are also known to have Iglas. Alleged Operatives of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam a rebel organization fighting for a homeland for Tamils in the island of Sri Lanka were arrested in August 2006 by undercover agents of the FBI posing as arms dealers, while trying to purchase the Igla. In 2003 the unit cost was approximately US$60,000–80,000.

Large numbers have been sold to the government of Venezuela, raising United States concerns that they may end up in the hands of Colombian guerrillas.[42] Photo evidence of the truck mounted twin version in service with the Libyan Army emerged in March 2011. 482 Igla-S missiles were imported from Russia in 2004. Some were unaccounted at the end of the civil war and they could have ended up in Iranian inventory.[43][44][45] Israeli officials say Igla-S systems were looted from Libyan warehouses in 2011 and transported by Iranians through Sudan and turned over to militants in Gaza and Lebanon.[46]

Igla-1E (SA-16)

Current operators

Al-Shabaab[47]

Al-Shabaab[47] Angola

Angola Armenia

Armenia Bosnia and Herzegovina: 20 pieces.

Bosnia and Herzegovina: 20 pieces. Botswana[48]

Botswana[48] Bulgaria: Produced locally by VMZ Sopot.[49]

Bulgaria: Produced locally by VMZ Sopot.[49] Croatia

Croatia Cuba

Cuba Ecuador

Ecuador Georgia

Georgia Hungary

Hungary Hezbollah[50]

Hezbollah[50] Iran

Iran Iraq[51]

Iraq[51] Kazakhstan[52]

Kazakhstan[52] Malaysia: 40 Djigit launchers, 382 MANPADS bought in 2002[53]

Malaysia: 40 Djigit launchers, 382 MANPADS bought in 2002[53] Myanmar : Licenced production since 2004.According to Arms Trade RTF by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute,1000 SA-16 have been produced as of 2014.[54]

Myanmar : Licenced production since 2004.According to Arms Trade RTF by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute,1000 SA-16 have been produced as of 2014.[54] North Korea: Locally produced.[49]

North Korea: Locally produced.[49] South Korea: Imported SA-16 from Russia as debt repayment by Russia to South Korea.[55]

South Korea: Imported SA-16 from Russia as debt repayment by Russia to South Korea.[55] Peru: SA-16. Upgrades/improvements by Diseños Casanave.[56]

Peru: SA-16. Upgrades/improvements by Diseños Casanave.[56] Romania: Igla-1M for marine forces and on Delfinul submarine.

Romania: Igla-1M for marine forces and on Delfinul submarine. Russia

Russia Serbia

Serbia Sri Lanka: provided by India in 2007, 54 operational as of 2020[57]

Sri Lanka: provided by India in 2007, 54 operational as of 2020[57] Singapore: Produced under license.[58]

Singapore: Produced under license.[58] South Sudan[59]

South Sudan[59] Ukraine

Ukraine United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates Vietnam Produce under license.[58] 48 launchers supplied in 2001-2002.[53]

Vietnam Produce under license.[58] 48 launchers supplied in 2001-2002.[53]

Vietnam People's Navy (400 missiles)[60]

Vietnam People's Navy (400 missiles)[60]

Former operators

Finland: known as ItO 86; former operator.

Finland: known as ItO 86; former operator. East Germany: Received around 1988-1989, passed on to successor states.

East Germany: Received around 1988-1989, passed on to successor states. Soviet Union: Passed on to successor states.

Soviet Union: Passed on to successor states. UNITA[47]

UNITA[47] Islamic Courts Union[47]

Islamic Courts Union[47] Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam[61]

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam[61]

Evaluation-only operators

Poland: Skarżysko-Kamienna plant produced a derivative, as Grom[49]

Poland: Skarżysko-Kamienna plant produced a derivative, as Grom[49]

Igla (SA-18)

Current operators

Armenia

Armenia Belarus

Belarus Brazil

Brazil Bulgaria

Bulgaria Cuba

Cuba Ecuador

Ecuador Egypt

Egypt Eritrea

Eritrea Georgia[62]

Georgia[62] Hungary

Hungary Indonesia

Indonesia India: 2,500 launchers supplied in 2001-2002[53]

India: 2,500 launchers supplied in 2001-2002[53] Iran

Iran Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan North Macedonia

North Macedonia Myanmar

Myanmar Malaysia

Malaysia Mexico: 50 launchers supplied in 2002[53]

Mexico: 50 launchers supplied in 2002[53]

Morocco

Morocco Mongolia

Mongolia North Korea Locally produced[63]

North Korea Locally produced[63] Peru

Peru Russia

Russia Singapore

Singapore

Slovakia

Slovakia Slovenia

Slovenia Serbia

Serbia Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Slovakia

Slovakia Thailand

Thailand Ukraine

Ukraine Vietnam

Vietnam Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Former operators

Finland: Known as ItO-86M; former operator

Finland: Known as ItO-86M; former operator Soviet Union: Passed on to successor states

Soviet Union: Passed on to successor states Hizbul Islam[64]

Hizbul Islam[64]

Igla-S (SA-24)

Current operators

Armenia: 200 missiles.[67] Received more as of 2018.[68]

Armenia: 200 missiles.[67] Received more as of 2018.[68] Azerbaijan: 300 launchers with 1500 missiles.[69]

Azerbaijan: 300 launchers with 1500 missiles.[69] Brazil

Brazil Libya

Libya Myanmar

Myanmar Islamic State Sinai Province[70]

Islamic State Sinai Province[70] Russia

Russia Slovenia

Slovenia.svg.png.webp) Syrian rebels: Photo evidence of SA-24 MANPADS (man-portable) in the possession of Syrian rebels was first reported on 13 November 2012. "As far as I know, this is the first SA-24 Manpads ever photographed outside of state control," said one expert.[71]

Syrian rebels: Photo evidence of SA-24 MANPADS (man-portable) in the possession of Syrian rebels was first reported on 13 November 2012. "As far as I know, this is the first SA-24 Manpads ever photographed outside of state control," said one expert.[71] Thailand[72]

Thailand[72] Venezuela[73]

Venezuela[73] Vietnam[74]

Vietnam[74]

Potential operators

Bangladesh: In March 2018, a tender was issued for procuring 181 Man-portable air-defense systems. Here, Chinese FN-16, Russian Igla-S and Swedish RBS 70 systems has been shortlisted.[75]

Bangladesh: In March 2018, a tender was issued for procuring 181 Man-portable air-defense systems. Here, Chinese FN-16, Russian Igla-S and Swedish RBS 70 systems has been shortlisted.[75]

Failed bids

Finland: Newer models were offered to the Finnish Army to replace older models in service, but American FIM-92 Stinger was selected instead.[76]

Finland: Newer models were offered to the Finnish Army to replace older models in service, but American FIM-92 Stinger was selected instead.[76]

Other uses

- The GLL-8 (Gll-VK) Igla is a recent Russian scramjet project conducted by TsIAM.

See also

- List of Russian weaponry

- Anza

- Misagh-2

- RBS 70

- Starstreak

- Mistral

References

- Hollybats (16 December 2014). "Isis Syria War FSA fire an Igla SAM at a regime aircraft over Nebbel 16.12.2014" – via YouTube.

- SA-18 Grouse 9K38 Igla man-portable missile technical data sheet specifications description pictures | Russia Russian army light heavy weapons UK | Russia Russian army military equipment vehicles UK Archived 1 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Armyrecognition.com (18 December 2011). Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- "9К338 Игла-С – SA-24 GRINCH". Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- 9K338 9M342 Igla-S / SA-24 Grinch Archived 4 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved on 6 January 2017.

- New Russian Verba MANPADS will replace Igla-S Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine - Armyrecognition.com, 15 September 2014

- ""Игла-1" и "Игла" / Оружие современной пехоты. Иллюстрированный справочник Часть II". www.nnre.ru. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- DJIGIT (SA-18). warfare.be

- https://armstrade.org/includes/periodics/news/2021/0127/101561429/detail.shtml

- New-generation man-portable air defence system Verba revealed to public at Army 2015 exhibition Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine – Armyrecognition.com, 19 June 2015

- Harish Kapadia. Siachen Glacier: The Battle of Roses. Rupa Publications Pvt. Ltd. (India).

- Lawrence, Richard R.. Mammoth Book Of How It Happened: Battles, Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2002.

- Statement on the Loss of RAF Tornado Aircraft in Combat During the Conduct of Air Operations against Iraq Archived 11 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Raf.mod.uk. Retrieved on 6 January 2017.

- "Aircraft Database on F-16.net" Archived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Aircraft profile records for Tail 84-1390. Retrieved: 11 May 2011.

- The Continuing Threat of Libyan Missiles Archived 8 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Stratfor. Retrieved on 6 January 2017.

- Cooper, Tom. "Peru vs. Ecuador; Alto Cenepa War, 1995". ACIG.org. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- Fulghum, David A. (14 January 2010) Anti-Aircraft Missiles Stolen by Guerrillas in Peru. Aviation Week

- "Serbs free two French pilots". USA Today. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Chechen gets life for killing 127 Russian soldiers, The Guardian, 30 April 2004

- A calamity, yet no end of war in sight Archived 12 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Economist, 22 August 2002

- Binnie, Jeremy. "Egyptian militants downed helo with Igla-type MANPADS". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- BOOK REVIEW – Apache Over Libya | Naval Historical Foundation Archived 6 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Navyhistory.org (2 September 2016). Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- Army Apache crew members honoured for actions over Libya – Announcements Archived 24 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. GOV.UK (26 March 2012). Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- Binnie, Jeremy (22 March 2015) Libya Dawn aircraft crashes during raid on Zintan. London, IHS Jane's Defence Weekly

- Michael Horowitz on Twitter: "Picture: Igla manpad reportedly used to shoot down a #Libya Dawn Airplane that carried out an airstrike over Zintan http://t.co/65DONM1RRq" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Twitter.com. Retrieved on 6 January 2017.

- "Three Men Charged with Smuggling Missiles". Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Ambuy Gem Corp". Manta. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "FBI's press release". FBI. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales Highlights Success in the War on Terror at the Council on Foreign Relations". US Department of Justice. 1 December 2005. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "حركة حزم التصدي للطيران الحربي فوق بلدة حيش". Archived from the original on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- Small Arms Survey (2015). "Trade Update: After the 'Arab Spring'" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2015: weapons and the world (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 107. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- Luhn, Alec (14 June 2014). "Bloodiest day in Ukraine conflict as rebel missiles bring down military jet". Observer. Archived from the original on 15 June 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- "BBC News – Azerbaijan downs Armenian helicopter". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Harro Ranter. "ASN Aircraft accident 12-NOV-2014 Mil Mi-24". Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Ağdamda helikopterin vurulma anı (həqiqi görüntülər)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Cunningham, Erin. (14 May 2016) Kurdish militants reportedly shoot down Turkish security forces helicopter Archived 18 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post. Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- Kwasek, Tomasz (18 August 2011) Przeciwlotniczy zestaw rakietowy PPZR Grom i Piorun. dziennikzbrojny.pl

- StarStreak High Velocity Missile (HVM) Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. thalesgroup.com

- STARSTREAK Armoured Vehicle System (AVS) Archived 7 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. thalesgroup.com

- http://ugcsurvival.com/FieldManuals/FM%201-140%2019960329-Helicopter%20Gunnery.pdf

- Starstreak – Close Air Defence Missiles Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Defencejournal.com. Retrieved on 6 January 2017.

- Forero, Juan (15 December 2010). "Venezuela acquired 1,800 Russian antiaircraft missiles in '09". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

leak

- SA-24 Grinch 9K338 Igla-s portable air defense missile system technical data sheet specifications UK Archived 20 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Army Recognition (23 March 2011). Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- Coughlin, Con (22 September 2011). "Iran 'steals surface-to-air missiles from Libya'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- The deadly dilemma of Libya's missing weapons Archived 3 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine. CSMonitor.com (7 September 2011). Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- Fulghum, David (13 August 2012). "Israel's Long Reach Exploits Unmanned Aircraft". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- "Guided light weapons reportedly held by non-state armed groups 1998-2013" (PDF). Small Arms Survey. March 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Martin, Guy. "Botswana - defenceWeb". www.defenceweb.co.za. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- Small Arms Survey 2004, p. 82.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Small Arms Survey 2004, p. 83.

- Small Arms Survey (2012). "Blue Skies and Dark Clouds: Kazakhstan and Small Arms". Small Arms Survey 2012: Moving Targets. Cambridge University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-521-19714-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Small Arms Survey 2004, p. 87.

- "SIPRI Trade Register". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- http://www.segye.com/newsView/20120522022045

- https://web.archive.org/web/20180816154534/http://www.discasanave.com/productos-militares/optimizacion-de-cohetes-y-misiles

- "341 Indra Radar Spares worth LKR 200 million gifted by India". newswire.lk. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- Small Arms Survey (2004). "Big Issue, Big Problem?: MANPADS" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2004: Rights at Risk. Oxford University Press. p. 81. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- Military Balance 2017

- "Thống kê hợp đồng mua sắm đạn dược của Việt Nam". Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Small Arms Survey 2004, p. 89.

- "SA-16 (Gimlet) / 9K310 Igla-1 Man-Portable, Shoulder-Launched Anti-Aircraft Missile System - Soviet Union". Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Small Arms Survey (2008). "Light Weapons: Products, Producers, and Proliferation". Small Arms Survey 2008: Risk and Resilience. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-88040-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- https://www.aselsan.com.tr/en/capabilities/air-and-missile-defense-systems/air-and-missile-defense-systems/missileigla-launching-system

- https://www.rostec.ru/en/news/4516471/

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute – Trade Register Archived 13 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, entries for Armenia 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "Armenia receives $200mln worth of weapons from Russia". TASS. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- APA – List of weapons and military vehicles sold by Russia to Azerbaijan last year publicized Archived 22 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. En.apa.az (19 June 2013). Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- Blanchard, Christopher M.; Humud, Carla E. (2 February 2017). "The Islamic State and U.S. Policy" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Chivers, C.J. (13 November 2012). "Possible Score for Syrian Rebels: Pictures Show Advanced Missile Systems". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- จรวดต่อสู้อากาศยาน SA-24 Grinch Igla-S Archived 10 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Venezuela compra en Rusia sistemas portátiles de defensa antiaérea. Vedomosti | Noticias | RIA Novosti Archived 23 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Sp.rian.ru (19 November 2008). Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- ’Kẻ hủy diệt’ trực thăng của Phòng không Việt Nam – ’Ke huy diet’ truc thang cua Phong khong Viet Nam – DVO – Báo Đất Việt Archived 17 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Baodatviet.vn (14 March 2013). Retrieved on 2017-01-06.

- "Tender for surface to air missile" (PDF). DGDP. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Gromy nie dla Finlandii - DziennikZbrojny.pl". Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 9K38 Igla. |