A Few Good Men

A Few Good Men is a 1992 American legal drama film based on Aaron Sorkin's 1989 play of the same name. Directed by Rob Reiner, who produced the film with David Brown and Andrew Scheinman was written from a screenplay by Sorkin himself and stars an ensemble cast, including Tom Cruise, Jack Nicholson, Demi Moore, Kevin Bacon, Kevin Pollak, J. T. Walsh, Cuba Gooding Jr. and Kiefer Sutherland.

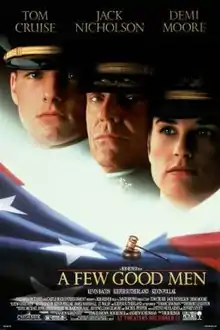

| A Few Good Men | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Rob Reiner |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | Aaron Sorkin |

| Based on | A Few Good Men by Aaron Sorkin |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Marc Shaiman |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | Robert Leighton |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $33–40 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $243.2 million[1] |

The film revolves around the court-martial of two U.S. Marines charged with the murder of a fellow Marine and the tribulations of their lawyers as they prepare a case to defend their clients.

Produced by Castle Rock Entertainment, the film was released by Columbia Pictures on December 11, 1992 and premiered on December 9, 1992 at Westwood. The film received universal acclaim for its screenwriting, direction, themes and acting (particuarly that of Cruise's, Nicholson's and Moore's) and became a box office hit with grossing over $243 million against a budget of $40 million.

In addition to its critical and commercial success, the film was nominated for four Academy Awards including Best Picture.[3]

Plot

U.S. Marines Lance Corporal Harold Dawson (Wolfgang Bodison) and Private First Class Louden Downey (James Marshall) are facing a general court-martial, accused of murdering fellow Marine William Santiago at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. Santiago had poor relations with his fellow Marines, compared unfavorably to them, and broke the chain of command in an attempt to get transferred out of Guantanamo. Base Commander Colonel Nathan Jessup (Jack Nicholson) and his officers argue about the best course of action: while Jessup's executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Markinson (J. T. Walsh), advocates that Santiago be transferred, Jessup dismisses the option and instead orders Santiago's commanding officer, Lieutenant Jonathan James Kendrick (Kiefer Sutherland), to "train" Santiago to become a better Marine.

While it is believed that the motive in Santiago's murder was retribution for naming Dawson in a fenceline shooting, Naval investigator and lawyer Lieutenant Commander JoAnne Galloway (Demi Moore) largely suspects Dawson and Downey carried out a "code red" order: a violent extrajudicial punishment. Galloway wants to defend the two, but the case is given to Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Daniel Kaffee (Tom Cruise) – an inexperienced and unenthusiastic lawyer with a penchant for plea bargains. Galloway and Kaffee instantly conflict, with Galloway unsettled by Kaffee's apparent laziness whilst Kaffee resents Galloway's interference. Kaffee and Galloway travel to Guantanamo base Cuba to question Colonel Jessup and others. Under questioning, Jessup claims Santiago was set to be transferred the next day.

When Kaffee negotiates a plea bargain with the prosecutor Captain Jack Ross, Dawson and Downey refuse to go along, insisting that Kendrick had indeed given them the "code red" order and that they never intended Santiago to die. Dawson shows outright contempt for Kaffee, refusing to salute or acknowledge him as an officer because Dawson sees him as having no honor by choosing a plea bargain over defending their actions. Lt. Col Markinson disappears. Kaffee plans to have himself removed as counsel as he sees going to trial as pointless. At the arraignment, Kaffee unexpectedly enters a plea of not guilty, explaining to Galloway and Weinberg that he realized the reason he was chosen to handle this case was because it was expected he would accept a plea, and the matter would be kept quiet.

After the case begins, Markinson later reveals himself to Kaffee and states, unequivocally, that Jessup never ordered a transfer for William Santiago. The defense manages to establish that Cpl Dawson had been denied promotion for smuggling food to a Marine who had been sentenced to go without food, painting Dawson in a good light and proving "code reds" had been ordered before. However, the defense then suffer two major setbacks: Downey, under cross-examination, reveals he was not actually present when Dawson received the supposed "code red" order, and Markinson, after he tells Kaffee that Jessup never ordered the transfer, but, ashamed that he failed to protect a Marine under his command, commits suicide before he can testify.

Without Markinson's testimony, Kaffee believes the case lost. He later returns home in a drunken stupor, lamenting that he fought the case instead of taking a deal. Galloway encourages Kaffee to call Jessup as a witness, despite the risk of being court-martialed for smearing a high-ranking officer. Jessup spars evenly with Kaffee's questioning, but is unnerved when Kaffee points out a contradiction in his testimony: Jessup stated his Marines never disobey orders and that Santiago was to be transferred for his own safety; if, Kaffee asks, Jessup ordered his men to leave Santiago alone, then how could Santiago be in danger? Irate at being caught in a lie and disgusted by what he sees as Kaffee's impudence towards the Marines, Jessup extols the military's importance, and his own, to national security. When asked point-blank if he ordered the "code red", Jessup continues with his self-important rant until, after repeatedly being asked the question, he bellows with contempt that, in fact, he did order the "code red." Jessup tries to leave the courtroom but is promptly arrested.

Dawson and Downey are cleared of the murder and conspiracy charges, but found guilty of "conduct unbecoming" and ordered to be dishonorably discharged. Dawson accepts the verdict, but Downey does not understand what they did wrong. Dawson explains that they had failed to defend those too weak to fight for themselves, like Santiago. As the two are leaving, Kaffee tells Dawson that he does not need to wear a patch on his arm to have honor. Dawson sheds his previous contempt for Kaffee, acknowledges him as an officer, and renders a salute. The film ends with Kaffee and Ross exchanging kudos before Ross departs to arrest Kendrick.

Cast

- Tom Cruise as Lieutenant (junior grade) Daniel Kaffee, USN, JAG Corps

- Jack Nicholson as Colonel Nathan R. Jessup, USMC

- Demi Moore as Lieutenant Commander JoAnne Galloway, USN, JAG Corps

- Kevin Bacon as Captain Jack Ross, USMC, Judge Advocate Division

- Kiefer Sutherland as First Lieutenant Jonathan James Kendrick, USMC

- Kevin Pollak as Lieutenant Sam Weinberg, USN, JAG Corps

- Wolfgang Bodison as Lance Corporal Harold W. Dawson, USMC

- James Marshall as Private Louden Downey, USMC

- J. T. Walsh as Lieutenant Colonel Matthew Andrew Markinson, USMC

- J. A. Preston as Judge Julius Alexander Randolph, USMC

- Michael DeLorenzo as Private William Santiago, USMC

- Noah Wyle as Corporal Jeffrey Owen Barnes, USMC

- Cuba Gooding Jr. as Corporal Carl Edward Hammaker, USMC

- Xander Berkeley as Captain Whitaker, USN

- Matt Craven as Lieutenant Dave Spradling, USN, JAG Corps

- John M. Jackson as Captain West, USN, JAG Corps

- Christopher Guest as Commander (Dr.) Stone, USN, MC

- Joshua Malina as Jessup's clerk

- Harry Caesar as newspaper stand operator Luther

Cast notes:

- Joshua Malina is the only actor to reprise his role from the original Broadway production.

- Aaron Sorkin makes a cameo appearance as a lawyer bragging in a tavern

Production

Screenwriter Aaron Sorkin got the inspiration to write the source play, a courtroom drama called A Few Good Men, from a phone conversation with his sister Deborah, who had graduated from Boston University Law School and signed up for a three-year stint with the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General's Corps.[4] She was going to Guantanamo Bay to defend a group of Marines who came close to killing a fellow Marine in a hazing ordered by a superior officer. Sorkin took that information and wrote much of his story on cocktail napkins while bartending at the Palace Theatre on Broadway.[5] His roommates and he had purchased a Macintosh 512K, so when he returned home, he would empty his pockets of the cocktail napkins and type them into the computer, forming a basis from which he wrote many drafts for A Few Good Men.[6]

In 1988, Sorkin sold the film rights for his play to producer David Brown before it premiered, in a deal reportedly "well into six figures".[7] Brown had read an article in The New York Times about Sorkin's one-act play Hidden in This Picture, and he found out Sorkin also had a play called A Few Good Men that was having off-Broadway readings.[8]

William Goldman did an uncredited rewrite of the script that Sorkin liked so much, he incorporated the changes made into the stage version.[9]

Brown was producing a few projects at TriStar Pictures, and he tried to interest them in making A Few Good Men into a film, but his proposal was declined due to the lack of star-actor involvement. Brown later got a call from Alan Horn at Castle Rock Entertainment, who was anxious to make the film. Rob Reiner, a producing partner at Castle Rock, opted to direct it.[8]

The film had a production budget of between $33 and 40 million.[2]

Nicholson would later comment on the $5 million he received for his role, "It was one of the few times when it was money well spent."[10]

The film starts with a performance of "Semper Fidelis" by a U.S. Marine Corps marching band, and a Silent Drill performed by the Texas A&M University Corps of Cadets Fish Drill Team (portraying the United States Marine Corps Silent Drill Platoon).[11][12]

Several former Navy JAG lawyers have been identified as the basis for Tom Cruise's character Lt. Kaffee. These include Don Marcari, now an attorney in Virginia; former U.S. Attorney David Iglesias; Chris Johnson, now practicing in California; and Walter Bansley III, now practicing in Connecticut. However, in a September 15, 2011, article in The New York Times, Sorkin was quoted as saying, “The character of Dan Kaffee in A Few Good Men is entirely fictional and was not inspired by any particular individual.”[13][14][15][16][17]

Wolfgang Bodison was a film location scout when he was asked to take part in a screen test for the part of Dawson.[18]

Reception

Box office

The film premiered at the Odeon Cinema, Manchester, England,[19] and opened on December 11, 1992, in 1,925 theaters. It grossed $15,517,468 in its opening weekend and was the number-one film at the box office for the next three weeks. Overall, it grossed $141,340,178 in the U.S. and $101,900,000 internationally for a total of $243,240,178.[20]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 83% based on 64 reviews, with an average rating of 7.09/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "An old-fashioned courtroom drama with a contemporary edge, A Few Good Men succeeds on the strength of its stars, with Tom Cruise, Demi Moore, and especially Jack Nicholson delivering powerful performances that more than compensate for the predictable plot."[21] On Metacritic the film has a score of 62 out of 100, based on 21 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews."[22] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A+" on an A+ to F scale, one of fewer than 60 films in the history of the service to earn the score.[23]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone magazine said, "That the performances are uniformly outstanding is a tribute to Rob Reiner (Misery), who directs with masterly assurance, fusing suspense and character to create a movie that literally vibrates with energy."[24] Richard Schickel in Time magazine called it "an extraordinarily well-made movie, which wastes no words or images in telling a conventional but compelling story."[25] Todd McCarthy in Variety magazine predicted, "The same histrionic fireworks that gripped theater audiences will prove even more compelling to filmgoers due to the star power and dramatic screw-tightening."[26] Roger Ebert was less enthusiastic in the Chicago Sun-Times, giving it two-and-a-half out of four stars and finding its major flaw was revealing the courtroom strategy to the audience before the climactic scene between Cruise and Nicholson. Ebert wrote, "In many ways this is a good film, with the potential to be even better than that. The flaws are mostly at the screenplay level; the film doesn't make us work, doesn't allow us to figure out things for ourselves, is afraid we'll miss things if they're not spelled out."[27]

Widescreenings noted that for Tom Cruise's character Daniel Kaffee, "Sorkin interestingly takes the opposite approach of Top Gun," where Cruise also starred as the protagonist. In Top Gun, Cruise plays Mitchell who is a "hotshot military underachiever who makes mistakes because he is trying to outperform his late father. Where Maverick Mitchell needs to rein in the discipline, Daniel Kaffee needs to let it go, finally see what he can do." Sorkin and Reiner are praised in gradually unveiling Kaffee's potential in the film.[28]

Home media

A Few Good Men was released on VHS and Laserdisc by Columbia TriStar Home Video on June 30, 1993, and was released on DVD on October 7, 1997. The VHS was again released along with a DVD release on May 29, 2001 and later a Blu-Ray release followed on September 8, 2007. The Double Feature of the film and Jerry Maguire was released on DVD on December 29, 2009 by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. A 4K UHD Blu-Ray release occurred on April 24, 2018.[29]

Awards and honors

Academy Awards nominations

The film was nominated for four Academy Awards:[30]

- Best Picture

- Best Supporting Actor (Jack Nicholson)

- Best Film Editing (Robert Leighton)

- Best Sound Mixing (Kevin O'Connell, Rick Kline and Robert Eber)

Golden Globe nominations

The film was nominated for five Golden Globe Awards:

- Best Motion Picture – Drama

- Best Director (Rob Reiner)

- Best Actor (Tom Cruise)

- Best Supporting Actor (Jack Nicholson)

- Best Screenplay (Aaron Sorkin)

Other honors

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Colonel Nathan R. Jessup – Nominated Villain[31]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- Col. Nathan Jessup: "You can't handle the truth!" – #29[32]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- #5 Courtroom Drama Film[33]

See also

References

- "A Few Good Men (1992 – Box Office Mojo)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- "A Few Good Men – budget". Nash Information Services. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- "The 65th Academy Awards". oscars.org. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- "4 Lawyers Claim to be the hero in a few good men," New York Times. 9.16.2011.

- "London Shows – A Few Good Men". thisistheatre.com. E&OE. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- "Aaron Sorkin interview". Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- Henry III, William (November 27, 1989). "Marine Life". Time. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008.

- Prigge, Steven (October 2004). Movie Moguls Speak: Interviews with Top Film Producers. McFarland & Company. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-7864-1929-6.

- "A Few Good Men (1992)". IMDb.

- Jack Nicholson. IMDb

- Daily Dose of Aggie History (December 11, 2016). "Dec. 11, 1992: A&M Fish Drill Team appears in 'A Few Good Men'". myAggieNation.com. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Nading, Tanya (February 11, 2001). "Corps Fish Drill Team reinstated — Front Page". College Media Network. Archived from the original on June 23, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- Glauber, Bill (April 10, 1994). "Ex-Marine who felt 'A Few Good Men' maligned him is mysteriously murdered". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- Gisick, Michael (May 10, 2007). "Fired U.S. Attorney David Iglesias embraces the media in his quest for vindication". The Albuquerque Tribune. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- Johnson, Christopher D. "Christopher D. Johnson, Esquire". Archived from the original on May 13, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- Beach, Randall (March 18, 2009). "Allegation delays homicide trial". New Haven Register. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2010.

- "Lawyer Didn't Act Like a "Few Good Men," Cops Say". NBC Connecticut. August 26, 2010. Retrieved October 28, 2010.

- Noted in the A Few Good Men DVD commentary

- "Historic Odeon faces final curtain". Manchester Evening News. February 15, 2007. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- "A Few Good Men – box office data". Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- "A Few Good Men (1992)". Fandango. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- "A Few Good Men reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- "CinemaScore". cinemascore.com.

- "Rotten Tomatoes – A Few Good Men review". Flixster Inc. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- Schickel, Richard (December 14, 1992). "Close-Order Moral Drill". Time Monday, Dec. 14, 1992. Time, Inc. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- McCarthy, Todd (November 12, 1992). "A Few Good Men – Review". RBI, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- Ebert, Roger (December 11, 1992). "A Few Good Men". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- "A Few Good Men DVD Release Date". DVDs Release Dates. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "The 65th Academy Awards (1993) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- "AFI's 10 Top 10: Top 10 Courtroom Drama". American Film Institute. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: A Few Good Men |