Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan

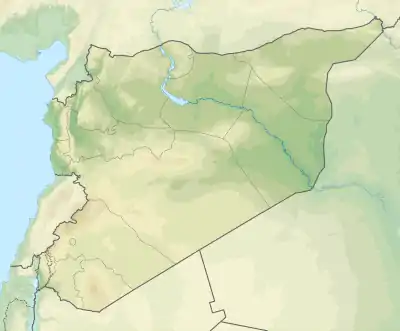

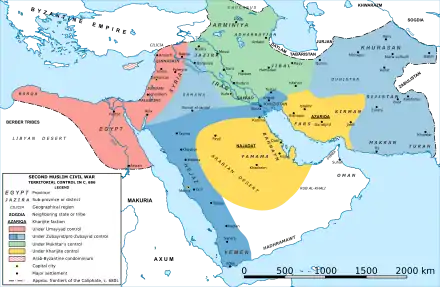

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ibn al-Hakam (Arabic: عبد الملك ابن مروان ابن الحكم, romanized: ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam; July/August 644 or June/July 647 – 9 October 705) was the fifth Umayyad caliph, ruling from April 685 until his death. A member of the first generation of born Muslims, his early life in Medina was occupied with pious pursuits. He held administrative and military posts under Caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), founder of the Umayyad Caliphate, and his own father, Caliph Marwan I (r. 684–685). By the time of Abd al-Malik's accession, Umayyad authority had collapsed across the Caliphate as a result of the Second Muslim Civil War and had been reconstituted in Syria and Egypt during his father's reign.

| Abd al-Malik عبد الملك | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amīr al-muʾminīn Khalīfat Allāh[lower-alpha 1] | |||||

| |||||

| 5th Caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 12 April 685 – 9 October 705 | ||||

| Predecessor | Marwan I | ||||

| Successor | Al-Walid I | ||||

| Born | July/August 644 or June/July 647 Medina, Rashidun Caliphate | ||||

| Died | 9 October 705 (Aged 61) Damascus, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | Outside of Bab al-Jabiya, Damascus | ||||

| Wives |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Marwanid | ||||

| Dynasty | Umayyad | ||||

| Father | Marwān I | ||||

| Mother | ʿĀʾisha bint Muʿāwiya ibn al-Mughīra | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

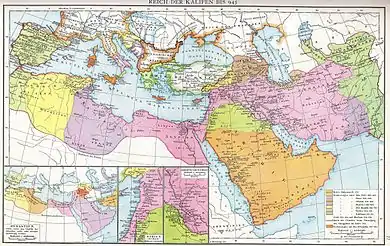

Following a failed invasion of Iraq in 686, Abd al-Malik focused on securing Syria before making further attempts to conquer the greater part of the Caliphate from his principal rival, the Mecca-based caliph Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr. To that end, he concluded an unfavorable truce with the reinvigorated Byzantine Empire in 689, quashed a coup attempt in Damascus by his kinsman, al-Ashdaq, the following year, and reincorporated into the army the rebellious Qaysi tribes of the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) in 691. He then conquered Zubayrid Iraq and dispatched his general, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, to Mecca where he killed Ibn al-Zubayr in late 692, thereby reuniting the Caliphate under Abd al-Malik's rule. The war with Byzantium resumed, resulting in Umayyad advances into Anatolia and Armenia, the destruction of Carthage and the recapture of Kairouan, the launchpad for the later conquests of western North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, in 698. In the east, Abd al-Malik's viceroy, al-Hajjaj, firmly established the caliph's authority in Iraq and Khurasan, stamping out opposition by the Kharijites and the Arab tribal nobility by 702. Abd al-Malik's final years were marked by a domestically peaceful and prosperous consolidation of power.

In a significant departure from his predecessors, rule over the Caliphate's provinces was centralized under Abd al-Malik, following the elimination of his rivals. Gradually, loyalist Arab troops from Syria were tasked with maintaining order in the provinces as dependence on less reliable, local Arab garrisons receded. Tax surpluses from the provinces were forwarded to Damascus and the traditional military stipends to veterans of the early Muslim conquests and their descendants were abolished, salaries being restricted to those in active service. The most consequential of Abd al-Malik's reforms were the introduction of a single Islamic currency in place of Byzantine and Sasanian coinage and the establishment of Arabic as the language of the bureaucracy in place of Greek and Persian in Syria and Iraq, respectively. His Muslim upbringing, the conflicts with external and local Christian forces and rival claimants to Islamic leadership all influenced Abd al-Malik's efforts to prescribe a distinctly Islamic character to the Umayyad state. Another manifestation of this initiative was his founding of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, the earliest archaeologically attested religious monument built by a Muslim ruler and the possessor of the earliest epigraphic proclamations of Islam and the prophet Muhammad. The foundations established by Abd al-Malik enabled his son and successor, al-Walid I (r. 705–715), who largely maintained his father's policies, to oversee the Umayyad Caliphate's territorial and economic zenith. Abd al-Malik's centralized government became the prototype of later medieval Muslim states.

Early life

Abd al-Malik was born in July/August 644 or June/July 647 in the house of his father Marwan ibn al-Hakam in Medina in the Hejaz (western Arabia).[8][9][lower-alpha 3] His mother was A'isha, a daughter of Mu'awiya ibn al-Mughira.[11][12] His parents belonged to the Banu Umayya,[11][12] one of the strongest and wealthiest clans of the Quraysh tribe.[13] The Islamic prophet Muhammad was a member of the Quraysh, but was ardently opposed by the tribe before they embraced Islam in 630. Not long after, the Quraysh came to dominate Muslim politics.[14] Abd al-Malik belonged to the first generation of born-Muslims and his upbringing in Medina, Islam's political center at the time, was generally described as pious and rigorous by the traditional Muslim sources.[8][15] He took a deep interest in Islam and possibly memorized the Qur'an.[16]

Abd al-Malik's father was a senior aide of their Umayyad kinsman, Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656).[8] In 656, Abd al-Malik witnessed Uthman's assassination in Medina,[11] an "event [that] had a lasting effect on him" and contributed to his "distrust" of the townspeople of Medina, according to the historian A. A. Dixon.[17] Six years later, Abd al-Malik distinguished himself in a campaign against the Byzantines as commander of a Medinese naval unit.[18][19][lower-alpha 4] He was appointed to the role by his distant cousin, Caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680), founder of the Umayyad Caliphate.[11] Afterward, he returned to Medina, where he operated under his father, who had become governor of the city,[8] as the kātib (secretary) of Medina's dīwān (bureaucracy).[18] As with the rest of the Umayyads in the Hejaz, Abd al-Malik lacked close ties with Mu'awiya, who ruled from his power base in Damascus in Syria.[8] Mu'awiya belonged to the Sufyanid line of the Umayyad clan, while Abd al-Malik belonged to the larger Abu al-As line. When a revolt broke out in Medina in 683 against Mu'awiya's son and successor, Caliph Yazid I (r. 680–683), the Umayyads, including Abd al-Malik, were expelled from the city.[11] The revolt was part of the wider anti-Umayyad rebellion that became known as the Second Muslim Civil War.[11] On the way to the Umayyad capital in Syria, Abd al-Malik encountered the army of Muslim ibn Uqba, who had been sent by Yazid to subdue the rebels in Medina.[11] He provided Ibn Uqba intelligence about Medina's defenses.[11] The rebels were defeated at the Battle of al-Harra in August 683, but the army withdrew to Syria after Yazid's death later that year.[11]

The deaths of Yazid and his son and successor Mu'awiya II in relatively quick succession in 683–684 precipitated a leadership vacuum in Damascus and the consequent collapse of Umayyad authority across the Caliphate.[21] Most provinces declared their allegiance to the rival Mecca-based caliph Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr.[22] In parts of Syria, older-established Arab tribes who had secured a privileged position in the Umayyad court and military, in particular the Banu Kalb, scrambled to preserve Umayyad rule.[21] Marwan and his family, including Abd al-Malik, had since relocated to Syria, where Marwan met the pro-Umayyad stalwart Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad, who had just been expelled from his governorship in Iraq. Ibn Ziyad persuaded Marwan to forward his candidacy for the caliphate during a summit of pro-Umayyad tribes in Jabiya hosted by the Kalbi chieftain Ibn Bahdal.[23] The tribal nobility elected Marwan as caliph and the latter became dependent on the Kalb and its allies, who collectively became known as the "Yaman" in reference to their ostensibly shared South Arabian (Yamani) roots.[23] Their power came at the expense of the Qaysi tribes, relative newcomers who had come to dominate northern Syria and the Jazira under Mu'awiya I and had defected to Ibn al-Zubayr.[23] The Qays were routed by Marwan and his Yamani backers at the Battle of Marj Rahit in 684, leading to a long-standing blood feud and rivalry between the two tribal coalitions.[23] Abd al-Malik did not participate in the battle on religious grounds, according to the contemporary poems compiled in the anthology of Abu Tammam (d. 845).[24]

Reign

Accession

Abd al-Malik was a close adviser of his father.[8] He was headquartered in Damascus and became its deputy governor during Marwan's expedition to conquer Zubayrid Egypt in late 684.[25] Upon the caliph's return in 685, he held a council in Sinnabra where he appointed Abd al-Malik governor of Palestine and designated him as his chosen successor,[26][27][28] to be followed by Abd al-Malik's brother, Abd al-Aziz.[29] This designation abrogated the succession arrangements reached in Jabiya, which stipulated Yazid's son Khalid would succeed Marwan, followed by another Umayyad, the former governor of Medina, Amr ibn Sa'id al-Ashdaq.[30] Nonetheless, Marwan secured the oaths of allegiance to Abd al-Malik from the Yamani nobility.[29] While the historian Gerald Hawting notes that Abd al-Malik was nominated despite his relative lack of political experience, Dixon maintains he was chosen "because of his political ability and his knowledge of statecraft and provincial administration", as indicated by his "gradual advance in holding important posts" from an early age.[25] Marwan died in April 685 and Abd al-Malik's accession as caliph was peacefully managed by the Yamani nobles.[8][15] He was proclaimed caliph in Jerusalem, according to a report by the 9th-century historian Khalifa ibn Khayyat, which the modern historian Amikam Elad considers to be seemingly "reliable".[28]

At the time of his accession, critical posts were held by members of Abd al-Malik's family.[8] His brother, Muhammad, was charged with suppressing the Qaysi tribes, while Abd al-Aziz maintained peace and stability as governor of Egypt until his death in 705.[8][31] During the early years of his reign, Abd al-Malik heavily relied on the Yamani nobles of Syria, including Ibn Bahdal al-Kalbi and Rawh ibn Zinba al-Judhami, who played key roles in his administration;[8] the latter served as the equivalent to the chief minister or wazīr of the later Abbasid caliphs.[32] Furthermore, a Yamani always headed Abd al-Malik's shurṭa (elite security retinue).[33] The first to hold the post was Yazid ibn Abi Kabsha al-Saksaki and he was followed by another Yamani, Ka'b ibn Hamid al-Ansi.[33][34][35] The caliph's ḥaras (personal guard) was typically led by a mawlā (non-Arab Muslim freedman; pl: mawālī) and staffed by mawālī.[33]

Early challenges

Though Umayyad rule had been restored in Syria and Egypt, Abd al-Malik faced several challenges to his authority.[8] Most provinces of the Caliphate continued to recognize Ibn al-Zubayr, while the Qaysi tribes regrouped under Zufar ibn al-Harith al-Kilabi and resisted Umayyad rule in the Jazira from al-Qarqisiya,[36] a Euphrates river fortress strategically located at the crossroads of Syria and Iraq.[37]

Failure in Iraq

Re-establishing Umayyad rule across the Caliphate was the major priority of Abd al-Malik.[36] His initial focus was the reconquest of Iraq, the Caliphate's wealthiest province.[33] Iraq was also home to a large population of Arab tribesmen,[33] the group from which the Caliphate derived the bulk of its troops.[38] In contrast, Egypt, which provided significant income to the treasury, possessed a small Arab community and was thus a meager source of troops.[39] The demand for soldiers was pressing for the Umayyads as the backbone of their military, the Syrian army, remained fractured along Yamani and Qaysi lines. Though the roughly 6,000 Yamani soldiers of Abd al-Malik's predecessor were able to consolidate the Umayyad position in Syria, they were too few to reassert authority throughout the Caliphate.[38] Ibn Ziyad, a key figure in the establishment of Marwanid power, set about enlarging the army by recruiting widely among the Arab tribes, including those which nominally belonged to the Qays faction.[38]

Ibn Ziyad had been tasked by Abd al-Malik's father with the reconquest of Iraq.[40] At the time, Iraq and its dependencies were split between the pro-Alid forces of al-Mukhtar al-Thaqafi in Kufa and the forces of Ibn al-Zubayr's brother Mus'ab in Basra. In August 686, Ibn Ziyad's 60,000-strong army was routed at the Battle of Khazir and he was slain, alongside most of his deputy commanders, at the hands of al-Mukhtar's much smaller pro-Alid force led by Ibrahim ibn al-Ashtar.[11][36] The decisive defeat and the loss of Ibn Ziyad represented a major setback to Abd al-Malik's ambitions in Iraq. He refrained from further major campaigns in the province for the next five years, during which Mus'ab defeated and killed al-Mukhtar and his supporters and became Iraq's sole ruler.[11][36]

Abd al-Malik shifted his focus to consolidating control of Syria.[36] His efforts in Iraq had been undermined by the Qaysi–Yamani schism when a Qaysi general in Ibn Ziyad's army, Umayr ibn al-Hubab al-Sulami, defected with his men mid-battle to join Zufar's rebellion.[38] Umayr's subsequent campaign against the large Christian Banu Taghlib tribe in the Jazira sparked a series of tit-for-tat raids and further deepened Arab tribal divisions, the previously neutral Taghlib throwing in its lot with the Yaman and the Umayyads.[41] The Taghlib killed Umayr in 689 and delivered his head to Abd al-Malik.[42]

Byzantine attacks and the treaty of 689

Along Syria's northern frontier, the Byzantines had been on the offensive since the failure of the First Arab Siege of Constantinople in 678.[43] In 679, a thirty-year peace treaty was concluded, obliging the Umayyads to pay an annual tribute of 3,000 gold coins, 50 horses and 50 slaves, and withdraw their troops from the forward bases they had occupied on the Byzantine coast.[44] The outbreak of the Muslim civil war allowed the Byzantine emperor Constantine IV (r. 668–685) to extort territorial concessions and enormous tribute from the Umayyads. In 685, the emperor led his army to Mopsuestia in Cilicia, and prepared to cross the border into Syria, where the Mardaites, an indigenous Christian group,[lower-alpha 5] were already causing considerable trouble. With his own position insecure, Abd al-Malik concluded a treaty whereby he would pay a tribute of 1,000 gold coins, a horse and a slave for every day of the year.[46]

Under Justinian II (r. 685–695, 705–711), the Byzantines became more aggressive, though it is unclear whether they intervened directly as reported by the 9th-century Muslim historian al-Baladhuri or used the Mardaites to mount pressure on the Muslims:[47] Mardaite depredations extended throughout Syria, as far south as Mount Lebanon and the Galilee uplands.[48] These raids culminated with the short-lived Byzantine recapture of Antioch in 688.[49] The setbacks in Iraq had weakened the Umayyads, and when a new treaty was concluded in 689, it greatly favoured the Byzantines: according to the 9th-century Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor, the treaty repeated the tribute obligations of 685, but now Byzantium and the Umayyads established a condominium over Cyprus, Armenia and Caucasian Iberia (modern Georgia), the revenue from which was to be shared between the two states. In exchange, Byzantium undertook to resettle the Mardaites in its own territory. The 12th-century Syriac chronicler Michael the Syrian, however, mentions that Armenia and Adharbayjan were to come under full Byzantine control. In reality, as the latter regions were not held by the Umayyads at this point, the agreement probably indicates a carte blanche by Abd al-Malik to the Byzantines to proceed against Zubayrid forces there. This arrangement suited both sides: Abd al-Malik weakened his opponent's forces and secured his northern frontier, and the Byzantines gained territory and reduced the power of the side that was apparently winning the Muslim civil war.[50] About 12,000 Mardaites were indeed resettled in Byzantium, but many remained behind, only submitting to the Umayyads in the reign of al-Walid I (r. 705–715). Their presence disrupted Umayyad supply lines and obliged them to permanently keep troops on standby to guard against their raids.[51]

The Byzantine counteroffensive represented the first challenge against a Muslim power by a people defeated in the early Muslim conquests.[43] Moreover, the Mardaite raids demonstrated to Abd al-Malik and his successors that the state could no longer depend on the quiescence of Syria's Christian majority, which until then had largely refrained from rebellion.[43] The modern historian Khalid Yahya Blankinship described the treaty of 689 as "an onerous and completely humiliating pact" and surmised that Abd al-Malik's ability to pay the annual tribute in addition to financing his own wartime army relied on treasury funds accrued during the campaigns of his Sufyanid predecessors and revenues from Egypt.[52]

Revolt of al-Ashdaq and end of the Qaysi rebellion

In 689/90, Abd al-Malik used the respite from the truce to initiate a campaign against the Zubayrids of Iraq, but was forced to return to Damascus when al-Ashdaq and his loyalists abandoned the army's camp and seized control of the city.[53] Al-Ashdaq viewed Abd al-Malik's accession as a violation of the caliphal succession agreement reached in Jabiya.[29] Abd al-Malik besieged his kinsman for sixteen days and promised him safety and significant political concessions if he relinquished the city.[11][53] Though al-Ashdaq agreed to the terms and surrendered, Abd al-Malik remained distrustful of the former's ambitions and executed him personally.[11]

Zufar's control of al-Qarqisiya, despite earlier attempts to dislodge him by Ibn Ziyad in 685/86 and the caliph's governor in Homs, Aban ibn al-Walid ibn Uqba, in 689/90, remained an obstacle to the caliph's ambitions in Iraq.[54] In revenge for Umayr's slaying, Zufar had intensified his raids and inflicted heavy casualties on the caliph's tribal allies in the Jazira.[55] Abd al-Malik resolved to command the siege of al-Qarqisiya in person in the summer of 691, and ultimately secured the defection of Zufar and the pro-Zubayrid Qays in return for privileged positions in the Umayyad court and army.[11][56][57] The integration of the Qaysi rebels strongly reinforced the Syrian army, and Umayyad authority was restored in the Jazira.[11] From then onward, Abd al-Malik and his immediate successors attempted to balance the interests of the Qays and Yaman in the Umayyad court and army.[58] This represented a break from the preceding seven years, during which the Yaman, and particularly the Kalb, were the dominant force of the army.[59]

Defeat of the Zubayrids

With threats in Syria and the Jazira neutralized, Abd al-Malik was free to focus on the reconquest of Iraq.[11][56] While Mus'ab had been bogged down fighting Kharijite rebels and contending with disaffected Arab tribesmen in Basra and Kufa, Abd al-Malik was secretly contacting and winning over these same Arab nobles.[41] Thus, by the time Abd al-Malik led the Syrian army into Iraq in 691, the struggle to recapture the province was virtually complete.[41] Command of the army was held by members of his family, his brother Muhammad leading the vanguard and Yazid I's sons Khalid and Abd Allah leading the right and left wings, respectively.[41] Many Syrian nobles held reservations about the campaign and counseled Abd al-Malik not to participate in person.[41] Nonetheless, the caliph was at the head of the army when it camped opposite Mus'ab's forces at Maskin, along the Dujayl Canal.[56] In the ensuing Battle of Maskin, most of Mus'ab's forces, many of whom were resentful at the heavy toll he had exacted on al-Mukhtar's Kufan partisans, refused to fight and his leading commander, Ibn al-Ashtar, fell at the beginning of hostilities.[56][60][61] Abd al-Malik invited Mus'ab to surrender in return for the governorship of Iraq or any other province of his choice, but the latter refused and was killed in action.[62]

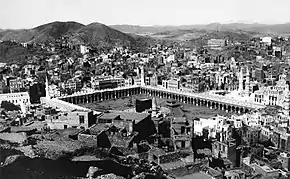

Following his victory, Abd al-Malik received the allegiance of Kufa's nobility and appointed governors to the Caliphate's eastern provinces.[63][lower-alpha 6] Afterward, he dispatched a 2,000-strong Syrian contingent to subdue Ibn al-Zubayr in the Hejaz.[66][67] The commander of the expedition, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, had risen through the ranks and would become a highly competent and efficient supporter of the caliph.[58] Al-Hajjaj remained encamped for several months in Ta'if, east of Mecca, and fought numerous skirmishes with Zubayrid loyalists in the plain of Arafat.[68] Abd al-Malik sent him reinforcements led by his mawlā, Tariq ibn Amr, who had earlier captured Medina from its Zubayrid governor.[69] In March 692, al-Hajjaj besieged Ibn al-Zubayr in Mecca and bombarded the Ka'aba, the holiest sanctuary in Islam, with catapults.[66][69] Though 10,000 of Ibn al-Zubayr's supporters, including his sons, eventually surrendered and received pardons, Ibn al-Zubayr and a core of his loyalists held out in the Ka'aba and were killed by al-Hajjaj's troops in September or October.[66][69] Ibn al-Zubayr's death marked the end of the civil war and the reunification of the Caliphate under Abd al-Malik.[66][70][71] In a panegyric that the literary historian Suzanne Stetkevych asserts was intended to "declare" and "legitimize" Abd al-Malik's victory, the caliph's Christian court poet al-Akhtal eulogized him on the eve or aftermath of Ibn al-Zubayr's fall as follows:

To a man whose gifts do not elude us, whom God has made victorious, so let him in his victory long delight!

He who wades into the deep of battle, auspicious his augury, the Caliph of God through whom men pray for rain.

When his soul whispers its intention to him it sends him resolutely forth, his courage and his caution like two keen blades.

In him the common weal resides, and after his assurance no peril can seduce him from his pledge.

— Al-Akhtal (640–708), Khaffat al-qaṭīnu ("The tribe has departed")[72]

After his victory, Abd al-Malik aimed to reconcile with the Hejazi elite, including the Zubayrids and the Alids, the Umayyads' rivals within the Quraysh.[73] He relied on the Banu Makhzum, another Qurayshi clan, as his intermediaries in view of the Umayyad family's absence in the region due to their exile in 683.[73] Nevertheless, he remained wary of the Hejazi elite's ambitions and kept a vigilant eye on them through his various governors in Medina.[73] The first of these was al-Hajjaj, who was also appointed governor of Yemen and the Yamama (central Arabia) and led the Hajj pilgrim caravans of 693 and 694.[66] Though he maintained peace in the Hejaz, the harshness of his rule led to numerous complaints from its residents and may have played a role in his transfer from the post by Abd al-Malik.[66] A member of the Makhzum and Abd al-Malik's father-in-law, Hisham ibn Isma'il, was ultimately appointed. During his tenure in 701–706 he was also known for brutalizing Medina's townspeople.[16]

Consolidation in Iraq and the east

Despite his victory, the control and governance of Iraq, a politically turbulent province from the time of the Muslim conquest in the 630s, continued to pose a major challenge for Abd al-Malik.[58] He had withdrawn the Syrian army and entrusted to the Iraqis the defense of Basra from the Kharijite threat.[41][74] Most Iraqis had become "weary of the conflict" with the Kharijites, "which had brought them little but hardship and loss", according to Gibb.[11] Those from Kufa, in particular, had grown accustomed to the wealth and comfort of their lives at home and their reluctance to undertake lengthy campaigns far from their families was an issue that previous rulers of Iraq had consistently encountered.[75][76] Initially, the caliph appointed his brother Bishr governor of Kufa and another kinsman, Khalid ibn Abdallah, to Basra before the latter too was put under Bishr's jurisdiction.[31] Neither governor was up to the task, but the Iraqis eventually defeated the Najdiyya Kharijites in the Yamama in 692/93.[74][77] The Azariqa Kharijites in Persia were more difficult to rein in,[77] and following Bishr's death in 694, the Iraqi troops deserted the field against them at Ramhormoz.[78]

Abd al-Malik's attempt at family rule in Iraq had proven unsuccessful, and he installed al-Hajjaj in the post instead in 694.[58] Kufa and Basra were combined into a single province under al-Hajjaj, who, from the start of his rule, displayed a strong commitment to governing Iraq effectively.[58] Against the Azariqa, al-Hajjaj backed al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra al-Azdi, a Zubayrid holdover with long experience combating the Kharijite rebels. Al-Muhallab finally defeated the Azariqa in 697.[58] Concurrently, a Kharijite revolt led by Shabib ibn Yazid al-Shaybani flared up in the heart of Iraq, resulting in the rebel takeover of al-Mada'in and siege of Kufa.[77] Al-Hajjaj responded to the unwillingness or inability of the war-weary Iraqis to face the Kharijites by obtaining from Abd al-Malik Syrian reinforcements led by Sufyan ibn al-Abrad al-Kalbi.[41][77] A more disciplined force, the Syrians repelled the rebel attack on Kufa and killed Shabib in early 697.[77][79] By 698, the Kharijite revolts had been stamped out.[80] Abd al-Malik attached to Iraq Sistan and Khurasan, thus making al-Hajjaj responsible for a super-province encompassing the eastern half of the Caliphate.[58] Al-Hajjaj made al-Muhallab deputy governor of Khurasan, a post he held until his death in 702, after which it was bequeathed to his son Yazid.[80][81] During his term, al-Muhallab recommenced the Muslim conquests in Central Asia, though the campaign reaped few territorial gains during Abd al-Malik's reign.[77]

Upon becoming governor, al-Hajjaj immediately threatened with death any Iraqi who refused to participate in the war efforts against the Kharijites.[58] In an effort to reduce expenditure, he had lowered the Iraqis' pay to less than that of their Syrian counterparts in the province.[58] By his measures, al-Hajjaj appeared "almost to have goaded the Iraqis into rebellion, as if looking for an excuse to break them", according to the historian Hugh Kennedy.[58] Indeed, conflict with the muqātila (Arab tribal forces who formed Iraq's garrisons) came to a head beginning in 699 when al-Hajjaj ordered Ibn al-Ash'ath to lead an expedition against Zabulistan.[80][82] Ibn al-Ash'ath and his commanders were wealthy and leading noblemen and bristled at al-Hajjaj's frequent rebukes and demands and the difficulties of the campaign.[82] In response, Ibn al-Ash'ath and his army revolted in Sistan, marched back and defeated al-Hajjaj's loyalists in Tustar in 701, and entered Kufa soon after.[82] Al-Hajjaj held out in Basra with his Banu Thaqif kinsmen and Syrian loyalists, who were numerically insufficient to counter the unified Iraqi front led by Ibn al-Ash'ath.[82] Alarmed at events, Abd al-Malik offered the Iraqis a pay raise equal to the Syrians and the replacement of al-Hajjaj with Ibn al-Ash'ath.[82] Due to his supporters' rejection of the terms, Ibn al-Ash'ath refused the offer, and al-Hajjaj took the initiative, routing Ibn al-Ash'ath's forces at the Battle of Dayr al-Jamajim in April.[82][83] Many of the Iraqis had defected after promises of amnesty if they disarmed, while Ibn al-Ash'ath and his core supporters fled to Zabulistan, where they were dispersed in 702.[82]

The suppression of the revolt marked the end of the Iraqi muqātila as a military force and the beginning of Syrian military domination of Iraq.[77][83] Iraqi internal divisions, and the utilization of disciplined Syrian forces by Abd al-Malik and al-Hajjaj, voided the Iraqis' attempt to reassert power in the province.[82] Determined to prevent further rebellions, al-Hajjaj founded a permanent Syrian garrison in Wasit, situated between the long-established Iraqi garrisons of Kufa and Basra, and instituted a more rigorous administration in the province.[82][83] Power thereafter derived from the Syrian troops, who became Iraq's ruling class, while Iraq's Arab nobility, religious scholars and mawālī were their virtual subjects.[82] Furthermore, the surplus taxes from the agriculturally rich Sawad lands were redirected from the muqātila to Abd al-Malik's treasury in Damascus to pay the Syrian troops in the province.[83][84] This reflected a wider campaign by the caliph to institute greater control over the Caliphate.[84]

Renewal of Byzantine wars in Anatolia, Armenia and North Africa

Despite the ten-year truce of 689, war with Byzantium resumed following Abd al-Malik's victory against Ibn al-Zubayr in 692.[77] The decision to resume hostilities was taken by Emperor Justinian II, ostensibly because of his refusal to accept payment of the tribute in the Muslim currency introduced that year rather than the Byzantine nomisma (see below).[77][85] This is reported solely by Theophanes and issues of chronology make this suspect; not all modern scholars accept its veracity.[86] The real casus belli, according to both Theophanes and the later Syriac sources, was Justinian's attempt to enforce his exclusive jurisdiction over Cyprus, and to move its population to Cyzicus in northwestern Anatolia, contrary to the treaty.[86][87] Given the enormous advantages secured by the treaty for Byzantium, Justinian's decision has been criticized by Byzantine and modern historians alike. However, the historian Ralph-Johannes Lilie points out that with Abd al-Malik emerging victorious from the civil war, Justinian may have felt it was only a matter of time until the caliph broke the treaty, and resolved to strike first, before Abd al-Malik could consolidate his position further.[88]

The Umayyads decisively defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Sebastopolis in 692 and parried a Byzantine counter-attack in 693/94 in the direction of Antioch.[77][89] Over the following years, the Umayyads launched constant raids against the Byzantine territories in Anatolia and Armenia, led by the caliph's brother Muhammad, and his sons al-Walid, Abd Allah, and Maslama, laying the foundation for further conquests in these areas under Abd al-Malik's successors, which would culminate in the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople in 717–718.[77][90] The military defeats inflicted on Justinian II contributed to the downfall of the emperor and his Heraclian dynasty in 695, ushering in a 22-year period of instability, in which the Byzantine throne changed hands seven times in violent revolutions, further aiding the Arab advance.[91][92] In 698/99, Emperor Tiberios III (r. 698–705) secured a treaty with the caliph for the return of the Cypriots, both those moved by Justinian II, as well as those subsequently deported by the Arabs to Syria, to their island.[93][94] Beginning in 700, Abd al-Malik's brother Muhammad subdued Armenia in a series of campaigns. The Armenians rebelled in 703 and received Byzantine aid, but Muhammad defeated them and sealed the failure of the revolt by executing the rebel princes in 705. As a result, Armenia was annexed into the Caliphate along with the principalities of Caucasian Albania and Iberia as the province of Arminiya.[95][96][97]

Meanwhile, in North Africa, a Byzantine–Berber alliance had reconquered Ifriqiya and slain its governor, Uqba ibn Nafi, in the Battle of Vescera in 682.[98] Abd al-Malik charged Uqba's deputy, Zuhayr ibn Qays, to reassert the Arab position in 688, but after initial gains, including the slaying of the Berber ruler Kasila at the Battle of Mams, Zuhayr was driven back to Barqa (Cyrenaica) by Kasila's partisans and slain by Byzantine naval raiders.[99] In 695, Abd al-Malik dispatched Hassan ibn al-Nu'man with a 40,000-strong army to retake Ifriqiya.[99][100] Hassan captured Byzantine-held Kairouan, Carthage and Bizerte.[99] With the aid of naval reinforcements sent by Emperor Leontios (r. 695–698), the Byzantines recaptured Carthage by 696/97.[99] After the Byzantines were repelled, Carthage was captured and destroyed by Hassan in 698,[77][100] signaling "the final, irretrievable end of Roman power in Africa", according to Kennedy.[101] Kairouan was firmly secured as a launchpad for later conquests, while the port town of Tunis was founded and equipped with an arsenal on the orders of Abd al-Malik, who was intent on establishing a strong Arab fleet.[77][100] Hassan continued his campaign against the Berbers, defeating them and killing their leader, the warrior queen al-Kahina, between 698 and 703.[99] Afterward, Hassan was dismissed by Abd al-Aziz, and replaced by Musa ibn Nusayr,[100] who went on to lead the Umayyad conquests of western North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula during the reign of al-Walid.[102]

Final years

The last years of Abd al-Malik's reign were generally characterized by the sources as a domestically peaceful and prosperous consolidation of power.[77] The blood feuds between the Qays and Yaman, which persisted despite the former's reconciliation with the Umayyads in 691, had dissipated toward the end of his rule.[103] Dixon credits this to Abd al-Malik's success at "harnessing tribal feeling to the interests of the government, [while] at the same time suppressing its violent manifestations".[103][lower-alpha 7]

The remaining principal issue faced by the caliph was ensuring the succession of his eldest son, al-Walid, in place of the designated successor, Abd al-Aziz.[77] The latter consistently refused Abd al-Malik's entreaties to step down from the line of succession, but potential conflict was avoided when Abd al-Aziz died in May 705.[77] He was promptly replaced as governor of Egypt by the caliph's son Abd Allah.[107] Abd al-Malik died five months later, on 9 October.[108] The cause of his death was attributed by the historian al-Asma'i (d. 828) to the 'Plague of the Maidens', so-called because it originated with the young women of Basra before spreading across Iraq and Syria.[109] He was buried outside of the Bab al-Jabiya gate of Damascus.[108]

Legacy

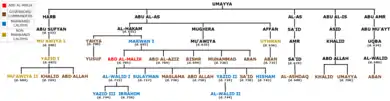

Abd al-Malik is considered the most "celebrated" Umayyad caliph by the historian Julius Wellhausen.[110] "His reign had been a period of hard-won successes", in the words of Kennedy.[81] The 9th-century historian al-Yaqubi described Abd al-Malik as "courageous, shrewd and sagacious, but also ... miserly".[34] His successor, al-Walid, continued his father's policies and his rule likely marked the peak of Umayyad power and prosperity.[75][111] Abd al-Malik's key administrative reforms, reunification of the Caliphate and suppression of all active domestic opposition enabled the major territorial expansion of the Caliphate during al-Walid's reign.[112] Three other sons of Abd al-Malik, Sulayman, Yazid II and Hisham, would rule in succession until 743, interrupted only by the rule of Abd al-Aziz's son, Umar II (r. 717–720).[75] With the exceptions of the latter and Marwan II (r. 744–750), all the Umayyad caliphs who came after Abd al-Malik were directly descended from him, hence the references to him as the "father of kings" in the traditional Muslim sources.[110] The Umayyad emirs and caliphs who ruled in the Iberian Peninsula between 756 and 1031 were also his direct descendants.[113] In the assessment of his biographer Chase F. Robinson, "Mu'awiya may have introduced the principle of dynastic succession into the ruling tradition of early Islam, but Abd al-Malik made it work".[113]

Abd al-Malik's concentration of power into the hands of his family was unprecedented; at one point, his brothers or sons held nearly all governorships of the provinces and Syria's districts.[114][115] Likewise, his court in Damascus was filled with far more Umayyads than under his Sufyanid predecessors, a result of the clan's exile to the city from Medina in 683.[116] He maintained close ties with the Sufyanids through marital relations and official appointments, such as according Yazid I's son Khalid a prominent role in the court and army and wedding to him his daughter A'isha.[31][117] Abd al-Malik also married Khalid's sister Atika, who became his favorite and most influential wife.[31]

After his victory in the civil war, Abd al-Malik embarked on a far-reaching campaign to consolidate Umayyad rule over the Caliphate.[84][118] The collapse of Umayyad authority precipitated by Mu'awiya I's death made it apparent to Abd al-Malik that the decentralized Sufyanid system was unsustainable.[84] Moreover, despite the defeat of his Muslim rivals, his dynasty remained domestically and externally insecure, prompting a need to legitimize its existence, according to Blankinship.[43] Abd al-Malik's solution to the fractious tribalism which defined his predecessors' caliphate was to centralize power.[77] At the same time, his response to the Byzantine–Christian resurgence and the criticism of Muslim religious circles, which dated from the beginning of Umayyad rule and culminated with the outbreak of the civil war, was to implement Islamization measures.[43][119] The centralized administration he established became the prototype of later medieval Muslim states.[84] In Kennedy's assessment, Abd al-Malik's "centralized, bureaucratic empire ... was in many ways an impressive achievement", but the political, economic and social divisions that developed within the Islamic community during his reign "was to prove something of a difficult inheritance for the later Umayyads".[120]

According to Wellhausen, government "evidently became more technical and hierarchical" under Abd al-Malik, though not nearly to the extent of the later Abbasid caliphs.[121] As opposed to the freewheeling governing style of the Sufyanids, Abd al-Malik ruled strictly over his officials and kept interactions with them largely formal.[122] He put an end to the provinces' retention of the lion's share of surplus tax revenues, as had been the case under the Sufyanids, and had them redirected to the caliphal treasury in Damascus.[123] He supported al-Hajjaj's policy of collecting the poll tax, traditionally imposed on the Caliphate's non-Muslim subjects, from the mawālī of Iraq and instructed Abd al-Aziz to implement this measure in Egypt, though the latter allegedly disregarded the order.[124] Abd al-Malik may have inaugurated several high-ranking offices, and Muslim tradition generally credits him with the organization of the barīd (postal service), whose principal purpose was to efficiently inform the caliph of developments outside of Damascus.[125] He built and repaired roads that connected Damascus with Palestine and linked Jerusalem to its eastern and western hinterlands, as evidenced by seven milestones found throughout the region,[126][127][128] the oldest of which dates to May 692 and the latest to September 704.[129][lower-alpha 8] The road project formed part of Abd al-Malik's centralization drive, special attention being paid to Palestine due to its critical position as a transit zone between Syria and Egypt and Jerusalem's religious centrality to the caliph.[132][133]

Institution of Islamic currency and Arabization of the bureaucracy

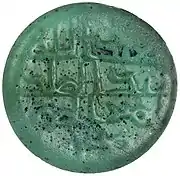

A major component of Abd al-Malik's centralization and Islamization measures was the institution of an Islamic currency.[43][84] The Byzantine gold solidus was discontinued in Syria and Egypt,[43][77] the likely impetus being the Byzantines' addition of an image of Christ on their coins in 691/92, which violated Muslim prohibitions on images of prophets.[134] To replace the Byzantine coins, he introduced an Islamic gold currency, the dinar, in 693.[77][135] Initially, the new coinage contained depictions of the caliph as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community and its supreme military commander.[43] This image proved no less acceptable to Muslim officialdom and was replaced in 696 or 697 with image-less coinage inscribed with Qur'anic quotes and other Muslim religious formulas.[135] In 698/99, similar changes were made to the silver dirhams issued by the Muslims in the former Sasanian Persian lands in the eastern Caliphate.[134] Depictions of the Sasanian king were consequently removed from the coinage,[134] though Abd al-Malik's new dirham retained its characteristically Sasanian silver fabric and wide flan.[136]

Shortly after the overhaul of the Caliphate's currency, in circa 700, Abd al-Malik is generally credited with the replacement of Greek with Arabic as the language of the dīwān in Syria.[135][137][138] The transition was carried out by his scribe Sulayman ibn Sa'd.[139] Al-Hajjaj had initiated the Arabization of the Persian dīwān in Iraq, three years before.[138] Though the official language was changed, Greek and Persian-speaking bureaucrats who were versed in Arabic kept their posts.[140] The Arabization of the bureaucracy and currency was the most consequential administrative reform undertaken by the caliph.[77] Arabic ultimately became the sole official language of the Umayyad state,[134] but the transition in faraway provinces, such as Khurasan, did not occur until the 740s.[141] According to Gibb, the decree was the "first step towards the reorganization and unification of the diverse tax-systems in the provinces, and also a step towards a more definitely Muslim administration".[77] Indeed, it formed an important part of the Islamization measures that lent the Umayyad Caliphate "a more ideological and programmatic coloring it had previously lacked", according to Blankinship.[142] In tandem, Abd al-Malik began the export of papyri containing the Muslim statement of belief in Greek to spread Islamic teachings in the Byzantine realm.[134] This was a further testament to the ideological expansion of the Byzantine–Muslim struggle.[134]

The increasingly Muslim character of the state under Abd al-Malik was partly a reflection of Islam's influence in the lives of the caliph and the chief enforcer of his policies, al-Hajjaj, both of whom belonged to the first generation of rulers born and raised as Muslims.[77] Having spent most of their lives in the Hejaz, the theological and legal center of Islam where Arabic was spoken exclusively and administrative offices were held solely by Arab Muslims, Abd al-Malik and his viceroy only understood Arabic and were unfamiliar with the Syrian and Greek Christian and Persian Zoroastrian officials of the dīwān.[143] They stood in stark contrast to the Sufyanid caliphs and their governors in Iraq, who had entered these regions as youths and whose children were as acquainted with the native majority as with the Arab Muslim newcomers.[143] According to Wellhausen, Abd al-Malik was careful not to offend his pious subjects "in the careless fashion of [Caliph] Yazid", but from the time of his accession "he subordinated everything to policy, and even exposed the Ka'ba to the danger of destruction", despite the piety of his upbringing and early career.[16] Dixon challenges this view, attributing the Abbasid-era Muslim sources' portrayal of Abd al-Malik's transformation in character after his accession and the consequent abandonment of his piety to their general hostility to Abd al-Malik, whom they variously "accused of being a mean, treacherous and blood-thirsty person".[24] Dixon nonetheless concedes that the caliph disregarded his early Muslim ideals when he felt political circumstances necessitated it.[24]

Reorganization of the army

Abd al-Malik shifted away from his predecessors' use of Arab tribal masses in favor of an organized army.[118][144] Likewise, Arab noblemen who had derived their power solely through their tribal standing and personal relations with a caliph were gradually replaced with military men who had risen through the ranks.[118][144] These developments have been partially obscured by the medieval sources due to their continued usage of Arab tribal terminology when referencing the army, such as the names of the tribal confederations Mudar, Rabi'a, Qays and Yaman.[118] According to Hawting, these do not represent the "tribes in arms" utilized by earlier caliphs; rather, they denote army factions whose membership was often (but not exclusively) determined by tribal origin.[118] Abd al-Malik also established a Berber-dominated private militia called al-Waḍḍāḥiya after their original commander, the caliph's mawlā al-Waddah, which helped enforce the authority of Umayyad caliphs through the reign of Marwan II.[145]

Under Abd al-Malik, loyalist Syrian troops began to be deployed throughout the Caliphate to keep order, which came largely at the expense of the tribal nobility of Iraq.[118] The latter's revolt under Ibn al-Ash'ath demonstrated to Abd al-Malik the unreliability of the Iraqi muqātila in securing the central government's interests in the province and its eastern dependencies.[118] It was following the revolt's suppression that the military became primarily composed of the Syrian army.[81] Consecrating this transformation was a fundamental change to the system of military pay, whereby salaries were restricted to those in active service. This marked an end to the system established by Caliph Umar (r. 634–644), which paid stipends to veterans of the earlier Muslim conquests and their descendants.[81] While the Iraqi tribal nobility viewed the stipends as their traditional right, al-Hajjaj viewed them as a handicap restricting his and Abd al-Malik's executive authority and financial ability to reward loyalists in the army.[81] Stipends were similarly stopped to the inhabitants of the Hejaz, including the Quraysh.[146] Thus, a professional army was established during Abd al-Malik's reign whose salaries derived from tax proceeds.[81] The dependence on the Syrian army of his successors, especially Hisham (r. 724–743), scattered the army among the Caliphate's multiple and isolated war fronts, most of them distant from Syria.[147] The growing strain and heavy losses inflicted on the Syrians by the Caliphate's external enemies and increasing factional divisions within the army contributed to the weakening and downfall of Umayyad rule in 750.[147][148]

Foundation of the Dome of the Rock

In 685/86 or 688, Abd al-Malik began planning the construction of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.[149] Its dedication inscription mentions the year 691/92, which most scholars agree is the completion date of the building.[150][151] It is the earliest archaeologically-attested religious structure to be built by a Muslim ruler and the building's inscriptions contain the earliest epigraphic proclamations of Islam and of the prophet Muhammad.[152] The inscriptions proved to be a milestone, as afterward they became a common feature in Islamic structures and almost always mention Muhammad.[152] The Dome of the Rock remains a "unique monument of Islamic culture in almost all respects", including as a "work of art and as a cultural and pious document", according to historian Oleg Grabar.[153]

-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Chain_(south_exposure).jpg.webp)

Narratives by the medieval sources about Abd al-Malik's motivations in building the Dome of the Rock vary.[153] At the time of its construction, the caliph was engaged in war with Christian Byzantium and its Syrian Christian allies on the one hand and with the rival caliph Ibn al-Zubayr, who controlled Mecca, the annual destination of Muslim pilgrimage, on the other hand.[153][154] Thus, one series of explanations was that Abd al-Malik intended for the Dome of the Rock to be a religious monument of victory over the Christians that would distinguish Islam's uniqueness within the common Abrahamic religious setting of Jerusalem, home of the two older Abrahamic faiths, Judaism and Christianity.[153][155] The other main explanation holds that Abd al-Malik, in the heat of the war with Ibn al-Zubayr, sought to build the structure to divert the focus of the Muslims in his realm from the Ka'aba in Mecca, where Ibn al-Zubayr would publicly condemn the Umayyads during the annual pilgrimage to the sanctuary.[153][154][155] Though most modern historians dismiss the latter account as a product of anti-Umayyad propaganda in the traditional Muslim sources and doubt that Abd al-Malik would attempt to alter the sacred Muslim requirement of fulfilling the pilgrimage to the Ka'aba, other historians concede this cannot be conclusively dismissed.[153][154][155] A last explanation has been to interpret the creation of the Haram al-Sharif complex as a monumental profession of faith, intended to proclaim the role of intercessor that the Prophet Muhammad was supposed to play on the day of the resurrection. The site was presented as the scene of the Last Judgement. The Dome of the Chain featured the divine courthouse, before which the deceased would appear before entering Heaven, represented by the Dome of the Rock.[156]

While his sons commissioned numerous architectural works, Abd al-Malik's known building activities were limited to Jerusalem.[157] As well as the Dome of the Rock, he is credited with constructing the adjacent Dome of the Chain,[158] expanding the boundaries of the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif) to include the Foundation Stone around which the Dome of the Rock was built and building two gates of the Temple Mount (possibly the Mercy Gate and the Prophet's Gate).[157][159] Theophanes, possibly conserving an original Syro-Palestinian Melkite source, reports that Abd al-Malik sought to remove some columns from a Christian shrine at Gethsemane to rebuild the Ka'aba, but he was dissuaded by his Christian treasurer, Sarjun ibn Mansur (the father of John of Damascus), and another leading Christian, called Patrikios, from Palestine, who successfully petitioned Emperor Justinian II to supply other columns instead.[93][160]

Family and residences

Abd al-Malik had children with several wives and ummahāt awlād (slave concubines; sing: umm walad). He was married to Wallada bint al-Abbas ibn al-Jaz, a fourth-generation descendant of the prominent Banu Abs chieftain Zuhayr ibn Jadhima.[161] She bore Abd al-Malik the sons al-Walid I, Sulayman, Marwan al-Akbar and a daughter, A'isha.[161] From Caliph Yazid I's daughter Atika, he had his sons Yazid II, Marwan al-Asghar, Mu'awiya and a daughter, Umm Kulthum.[117][161] His wife A'isha bint Hisham ibn Isma'il, whom he divorced,[162] belonged to the Makhzum clan and mothered Abd al-Malik's son Hisham.[161] He had a second wife from the Makhzum, Umm al-Mughira bint al-Mughira ibn Khalid, a fourth-generation descendant of the pre-Islamic leader of the Quraysh Hisham ibn al-Mughira, with whom he had a daughter, Fatima, who would later wed Umar II.[161][163] From his marriage to Umm Ayyub bint Amr, a granddaughter of Caliph Uthman, Abd al-Malik had his son al-Hakam,[161][164] who, according to the medieval Arab genealogists, died at a young age, contradicting a number of contemporary Arabic poems which suggest he lived into adulthood.[165] Abd al-Malik also married A'isha bint Musa, a granddaughter of one of the Islamic prophet Muhammad's leading companions, Talha ibn Ubayd Allah, and together they had a son, Bakkar, who was also known as Abu Bakr.[161][166] Abd al-Malik married and divorced during his caliphate Umm Abiha, a granddaughter of Ja'far ibn Abi Talib,[161][167][168] and Shaqra bint Salama ibn Halbas, a woman of the Banu Tayy.[161] Abd al-Malik's sons from his ummahāt awlād were Abd Allah, Maslama, Sa'id al-Khayr, al-Mundhir, Anbasa, Muhammad and al-Hajjaj,[161] the last named after the caliph's viceroy.[169] At the time of his death, fourteen of Abd al-Malik's sons had survived him, according to al-Yaqubi.[34]

Abd al-Malik divided his time between Damascus and seasonal residences in its general vicinity.[170][171] He spent the winter mostly in Damascus and Sinnabra near Lake Tiberias, then to Jabiya in the Golan Heights and Dayr Murran, a monastery village on the slopes of Mount Qasyoun overlooking the Ghouta orchards of Damascus.[170][171] He would typically return to the city in March and leave again in the heat of summer to Baalbek in the Beqaa Valley before heading back to Damascus in early autumn.[170][171]

Notes

- Amīr al-muʾminīn (commander of the faithful) is the most referenced formal title of Abd al-Malik in coins, inscriptions and the early Muslim literary tradition.[1][2][3] He is also referred to as khalīfat Allāh (caliph of God) in a number of coins minted in the mid-690s, correspondence from his viceroy al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf and poetic verses by his contemporaries al-Akhtal, Jarir and al-Farazdaq.[4][5]

- The general view among historians and numismatists is that the human figure depicted in the coins minted by Abd al-Malik between 693 and 697, which have come to be known as the "standing caliph" issue, represent Abd al-Malik.[6] The historian Robert Hoyland, however, argues that this may be a near-contemporary depiction of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[7]

- The consensus in the Islamic tradition is that Abd al-Malik was born in the Islamic calendar month of Ramadan, though no day is specified.[9] One set of traditional sources, including Khalifa ibn Khayyat (d. 854), al-Tabari (d. 923) citing al-Mada'ini (d. 843), al-Baladhuri (d. 892) and Ibn Asakir (d. 1175), hold Abd al-Malik was born in the year 23 AH, while another set of accounts, including Ibn Sa'd (d. 845), al-Tabari citing al-Waqidi (d. 823), Ibn Asakir, Ibn al-Athir (d. 1233) and al-Suyuti (d. 1505) hold he was born in 26 AH.[10]

- Abd al-Malik's counterpart in the Syrian naval unit during the winter sea campaign against the Byzantine Empire in c. 662 was Busr ibn Abi Artat or Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid ibn al-Walid.[19] According to the historian Marek Jankowiak, Abd al-Malik's military role against the Byzantines during the reign of Caliph Mu'awiya I (r. 661–680) was "expunged" from the generally anti-Umayyad, Abbasid-era Islamic tradition, but preserved in other Islamic traditions transmitted by the 10th-century Arabic Christian chronicler Agapius of Hierapolis.[20]

- The home of the Mardaites, a Christian people of unclear ethnic origins, known in Arabic as the "Jarājima", was the mountainous spine along the Syrian coast, namely the Amanus, Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon ranges. There, they held a significant degree of autonomy and shifted their nominal allegiance between the Byzantine Empire and the Caliphate, depending on political circumstances along the Arab–Byzantine front.[45]

- The semi-independent, pro-Zubayrid governor of Khurasan, Abd Allah ibn Khazim, rejected Abd al-Malik's entreaties in early 692 to recognize his caliphate in return for a confirmation of Ibn Khazim's governorship.[64] Ibn Khazim was soon after slain in a mutiny led by one his commanders, Bahir ibn Warqa, and his head was sent to the caliph by the lieutenant governor of Merv, Bukayr ibn Wishah, to whom Abd al-Malik subsequently conferred the governorship of Khurasan.[65]

- After the reconciliation of 691, violence between the Banu Kalb and the Qaysi Banu Fazara of the Hejaz flared up until 692–694.[104] The blood feud between the Qaysi Banu Sulaym and the Yamani-allied Banu Taghlib persisted until 692.[105] Abd al-Malik intervened in both cases and put a definitive end to the tit-for-tat raids by means of financial compensation, threat of force and executions of tribal chieftains.[106]

- The milestones, all containing inscriptions crediting Abd al-Malik for the road works, were found, from north to south, in or near Fiq, Samakh, St. George's Monastery of Wadi Qelt, Khan al-Hathrura, Bab al-Wad and Abu Ghosh. The milestone found in Samakh dates to 692, the two milestones at Fiq both date to 704 and the remaining milestones are undated.[130] The fragment of an eighth milestone, likely produced soon after Abd al-Malik's death, was found at Ein Hemed, immediately west of Abu Ghosh.[131]

References

- Crone & Hinds 1986, p. 11.

- Marsham 2018, pp. 7–8.

- Anjum 2012, p. 47.

- Crone & Hinds 1986, pp. 7–8.

- Marsham 2018, p. 7.

- Hoyland 2007, p. 594.

- Hoyland 2007, pp. 593–596.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 80.

- Dixon 1971, p. 15.

- Dixon 1971, p. 15, notes 1–2.

- Gibb 1960, p. 76.

- Ahmed 2010, p. 111.

- Della Vida 2000, p. 838.

- Donner 1981, pp. 77–78.

- Dixon 1971, p. 20.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 215.

- Dixon 1971, p. 16.

- Dixon 1971, p. 17.

- Jankowiak 2013, p. 264.

- Jankowiak 2013, p. 273.

- Kennedy 2016, pp. 78–79.

- Hawting 2000, p. 48.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 79.

- Dixon 1971, p. 21.

- Dixon 1971, p. 18.

- Mayer 1952, p. 185.

- Crone 1980, pp. 100, 125.

- Elad 1999, p. 24.

- Hawting 2000, p. 59.

- Hawting 2000, pp. 58–59.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 222.

- Hawting 1995, p. 466.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 35.

- Biesterfeldt & Günther 2018, p. 986.

- Crone 1980, p. 163.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 81.

- Streck 1978, pp. 654–655.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 32.

- Kennedy 2016, pp. 80–81.

- Bosworth 1991, p. 622.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 33.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 204.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 28.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 81–82.

- Eger 2015, pp. 295–296.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 101–102.

- Lilie 1976, p. 102.

- Eger 2015, p. 296.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 102–103.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 103–106, 109.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 106–107, note 13.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 27–28.

- Dixon 1971, p. 125.

- Dixon 1971, pp. 92–93.

- Dixon 1971, p. 102.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 84.

- Dixon 1971, p. 93.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 87.

- Kennedy 2016, pp. 86–87.

- Fishbein 1990, p. 181.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 195–196.

- Dixon 1971, pp. 133–134.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 197.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 420.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 421.

- Dietrich 1971, p. 40.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 197–198.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 198.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 199.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 200.

- Dixon 1971, p. 140.

- Stetkevych 2016, pp. 129, 136–137, 141.

- Ahmed 2010, p. 152.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 227.

- Hawting 2000, p. 58.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 229.

- Gibb 1960, p. 77.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 228–229.

- Kennedy 2001, pp. 33–34.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 231.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 89.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 88.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 34.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 85.

- Mango & Scott 1997, p. 509.

- Mango & Scott 1997, p. 510, note 1.

- Ditten 1993, pp. 308–314.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 107–110.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 110–112.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 112–116.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 31.

- Lilie 1976, p. 140.

- PmbZ, 'Abd al-Malik (#18/corr.).

- Ditten 1993, pp. 314–317.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 107.

- Ter-Ghewondyan 1976, pp. 20–21.

- Lilie 1976, pp. 113–115.

- Kaegi 2010, pp. 13–14.

- Kaegi 2010, p. 14.

- Talbi 1971, p. 271.

- Kennedy 2007, p. 217.

- Lévi-Provençal 1993, p. 643.

- Dixon 1971, p. 120.

- Dixon 1971, pp. 96–98.

- Dixon 1971, pp. 103–104.

- Dixon 1971, pp. 96–98, 103–104.

- Becker 1960, p. 42.

- Hinds 1990, pp. 125–126.

- Conrad 1981, p. 55.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 223.

- Kennedy 2002, p. 127.

- Dixon 1971, p. 198.

- Robinson 2005, p. 124.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 221–222.

- Bacharach 1996, p. 30.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 167, 222.

- Ahmed 2010, p. 118.

- Hawting 2000, p. 62.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 78.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 90.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 220–221.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 221.

- Kennedy 2016, pp. 72, 76, 85.

- Crone 1994, p. 14, note 63.

- Hawting 2000, p. 64.

- Sharon 1966, pp. 368, 370–372.

- Sharon 2004, p. 95.

- Elad 1999, p. 26.

- Bacharach 2010, p. 7.

- Sharon 2004, pp. 94–96.

- Cytryn-Silverman 2007, pp. 609–610.

- Sharon 1966, pp. 370–372.

- Sharon 2004, p. 96.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 94.

- Blankinship 1994, pp. 28, 94.

- Darley & Canepa 2018, p. 367.

- Hawting 2000, p. 63.

- Duri 1965, p. 324.

- Sprengling 1939, pp. 212–213.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 219–220.

- Hawting 2000, pp. 63–64.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 95.

- Sprengling 1939, pp. 193–195.

- Robinson 2005, p. 68.

- Athamina 1998, p. 371.

- Elad 2016, p. 331.

- Blankinship 1994, p. 236.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 30.

- Elad 1999, pp. 24, 44.

- Johns 2003, pp. 424–426.

- Elad 1999, p. 45.

- Johns 2003, p. 416.

- Grabar 1986, p. 299.

- Johns 2003, pp. 425–426.

- Hawting 2000, p. 60.

- Tillier, Mathieu. ‘Abd al-Malik, Muḥammad et le Jugement dernier : le dôme du Rocher comme expression d’une orthodoxie islamique, inLes vivants et les morts dans les sociétés médiévales. Actes du XLVIIIe Congrès de la SHMESP (Jérusalem, 2017), Éditions de la Sorbonne, Paris, 2018, p. 341-365. https://books.openedition.org/psorbonne/53878

- Bacharach 1996, p. 28.

- Elad 1999, p. 47.

- Elad 1999, pp. 25–26.

- Mango & Scott 1997, p. 510, note 5.

- Hinds 1990, p. 118.

- Blankinship 1989, pp. 1–2.

- Hinds 1991, p. 140.

- Ahmed 2010, p. 116.

- Ahmed 2010, p. 116, note 613.

- Ahmed 2010, p. 160.

- Ahmed 2010, p. 128.

- Madelung 1992, pp. 247, 260.

- Chowdhry 1972, p. 155.

- Kennedy 2016, p. 96.

- Bacharach 1996, p. 38.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Asad Q. (2010). The Religious Elite of the Early Islamic Ḥijāz: Five Prosopographical Case Studies. Oxford: University of Oxford Linacre College Unit for Prosopographical Research. ISBN 978-1-900934-13-8.

- Anjum, Ovamir (2012). Politics, Law, and Community in Islamic Thought: The Taymiyyan Moment. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01406-0.

- Athamina, Khalil (1998). "Non-Arab Regiments and Private Militias during the Umayyād Period". Arabica. Brill. 45 (3): 347–378. doi:10.1163/157005898774230400. JSTOR 4057316.

- Bacharach, Jere L. (1996). "Marwanid Umayyad Building Activities: Speculations on Patronage". Muqarnas Online. Brill. 13: 27–44. doi:10.1163/22118993-90000355. ISSN 2211-8993. JSTOR 1523250.

- Bacharach, Jere L. (2010). "Signs of Sovereignty: The "Shahāda", the Qurʾanic Verses, and the Coinage of ʿAbd al-Malik". Muqarnas Online. Brill. 27: 1–30. doi:10.1163/22118993_02701002. ISSN 2211-8993. JSTOR 25769690.

- Becker, C. H. (1960). "ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAbd al-Malik". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 42. OCLC 495469456.

- Biesterfeldt, Hinrich; Günther, Sebastian (2018). The Works of Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (Volume 3): An English Translation. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35621-4.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXV: The End of Expansion: The Caliphate of Hishām, A.D. 724–738/A.H. 105–120. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-569-9.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1991). "Marwān I b. al-Ḥakam". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 621–623. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Chowdhry, Shiv Rai (1972). Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf (An Examination of His Works and Personality) (Thesis). University of Delhi.

- Conrad, Lawrence I. (1981). "Arabic Plague Chronologies and Treatises: Social and Historical Factors in the Formation of a Literary Genre". Studia Islamica. 54 (54): 51–93. doi:10.2307/1595381. JSTOR 1595381. PMID 11618185.

- Crone, Patricia (1980). Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- Crone, Patricia; Hinds, Martin (1986). God's Caliph: Religious Authority in the First Centuries of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-32185-9.

- Crone, Patricia (1994). "Were the Qays and Yemen of the Umayyad Period Political Parties?". Der Islam. Walter de Gruyter and Co. 71 (1): 1–57. doi:10.1515/islm.1994.71.1.1. ISSN 0021-1818. S2CID 154370527.

- Cytryn-Silverman, Katia (2007). "The Fifth Mīl from Jerusalem: Another Umayyad Milestone from Southern Bilād al-Shām". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. Cambridge University Press. 70 (3): 603–610. doi:10.1017/S0041977X07000857. JSTOR 40378940.

- Darley, Rebecca; Canepa, Matthew (2018). "coinage, Persian". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Della Vida, Giorgio Levi (2000). "Umayya b. ʿAbd Shams". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 837–838. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Dietrich, Albert (1971). "Al-Ḥadjdjādj b. Yūsuf". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 39–43. OCLC 495469525.

- Ditten, Hans (1993). Ethnische Verschiebungen zwischen der Balkanhalbinsel und Kleinasien vom Ende des 6. bis zur zweiten Hälfte des 9. Jahrhunderts (in German). Berlin: Akademie Verlag. ISBN 3-05-001990-5.

- Dixon, 'Abd al-Ameer (1971). The Umayyad Caliphate, 65–86/684–705: (A Political Study). London: Luzac. ISBN 978-0718901493.

- Donner, Fred M. (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05327-8.

- Duri, Abd al-Aziz (1965). "Dīwān". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 323–327. OCLC 495469475.

- Eger, A. Asa (2015). The Islamic-Byzantine Frontier: Interaction and Exchange Among Muslim and Christian Communities. London and New York: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-157-2.

- Elad, Amikam (1999). Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10010-5.

- Elad, Amikam (2016). The Rebellion of Muḥammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya in 145/762: Ṭālibīs and Early ʿAbbāsīs in Conflict. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-22989-1.

- Fishbein, Michael, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXI: The Victory of the Marwānids, A.D. 685–693/A.H. 66–73. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0221-4.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960). "ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 76–77. OCLC 495469456.

- Grabar, O. (1986). "Kubbat al-Ṣakhra". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 298–299. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Hoyland, Robert (2007). "Writing the Biography of Muhammad". History Compass. 5: 581–602. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2007.00395.x.

- Hawting, G. R. (1995). "Rawḥ b. Zinbāʿ". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 466. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hinds, Martin, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIII: The Zenith of the Marwānid House: The Last Years of ʿAbd al-Malik and the Caliphate of al-Walīd, A.D. 700–715/A.H. 81–95. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-721-1.

- Hinds, M. (1991). "Makhzum". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 137–140. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Jankowiak, Marek (2013). "The First Arab Siege of Constantinople". In Zuckerman, Constantin (ed.). Travaux et mémoires, Vol. 17: Constructing the Seventh Century. Paris: Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance. pp. 237–320.

- Johns, Jeremy (January 2003). "Archaeology and the History of Early Islam: The First Seventy Years". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 46 (4): 411–436. doi:10.1163/156852003772914848. S2CID 163096950.

- Kaegi, Walter E. (2010). Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2002). "Al-Walīd (I)". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2007). The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81740-3.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Third ed.). Oxford and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-78761-2.

- Lévi-Provençal, E. (1993). "Mūsā b. Nuṣayr". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 643–644. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes (1976). Die byzantinische Reaktion auf die Ausbreitung der Araber. Studien zur Strukturwandlung des byzantinischen Staates im 7. und 8. Jhd (in German). Munich: Institut für Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie der Universität München. OCLC 797598069.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes; Ludwig, Claudia; Pratsch, Thomas; Zielke, Beate (2013). "'Abd al-Malik". Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit Online. Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Nach Vorarbeiten F. Winkelmanns erstellt (in German). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1992). Religious and Ethnic Movements in Medieval Islam. Aldershot, Hants: Variorum. ISBN 0-86078-310-3.

- Mango, Cyril; Scott, Roger (1997). The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor: Byzantine and Near Eastern History, AD 284–813. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822568-7.

- Marsham, Andrew (2018). ""God's Caliph" Revisited: Umayyad Political Thought in its Late Antique Context". In George, Alain; Marsham, Andrew (eds.). Power, Patronage, and Memory in Early Islam: Perspectives on Umayyad Elites. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-049893-1.

- Mayer, L. A. (1952). "As-Sinnabra". Israel Exploration Society. 2 (3): 183–187. JSTOR 27924483.

- Robinson, Chase F. (2005). Abd al-Malik. London: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-85168-361-1.

- Sharon, Moshe (June 1966). "An Arabic Inscription from the Time of the Caliph 'Abd al-Malik". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 29 (2): 367–372. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00058900.

- Sharon, Moshe (2004). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae (CIAP): D-F. Volume Three. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-04-13197-3.

- Sprengling, Martin (April 1939). "From Persian to Arabic". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. The University of Chicago Press. 56 (2): 175–224. doi:10.1086/370538. JSTOR 528934.

- Stetkevych, Suzanne Pinckney (2016). "Al-Akhṭal at the Court of ʿAbd al-Malik: The Qaṣīda and the Construction of Umayyad Authority". In Borrut, Antoine; Donner, Fred M. (eds.). Christians and Others in the Umayyad State. Late Antique and Medieval Islamic Near East. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 129–156. ISBN 978-1-614910-31-2.

- Streck, Maximilian (1978). "Karkīsiyā". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 654–655. OCLC 758278456.

- Talbi, M. (1971). "Ḥassān b. al-Nuʿmān al-Ghassānī". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 271. OCLC 495469525.

- Ter-Ghewondyan, Aram (1976) [1965]. The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. Translated by Nina G. Garsoïan. Lisbon: Livraria Bertrand. OCLC 490638192.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.

Further reading

- Clarke, Nicola (2018). "'Abd al-Malik b. Marwān". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Pezeshk, Manouchehr; Negahban, Farzin; Miller, Isabel (2008). "ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica Online. Brill Online. ISSN 1875-9831.

Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan Born: 646/47 Died: 9 October 705 | ||

| Preceded by Marwan I |

Caliph of Islam Umayyad Caliph 12 April 685 – 9 October 705 |

Succeeded by Al-Walid I |