Melkite

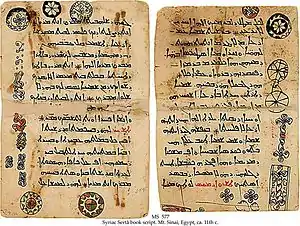

The term Melkite (/ˈmɛlkaɪt/), also written Melchite, refers to various Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in the Middle East. The term comes from the common Central Semitic root M-L-K,[lower-alpha 1] meaning "royal", and by extension "imperial" or loyal to the Byzantine Emperor.[1][2] The Melkites accepted the Council of Chalcedon. Originally they used Greek and, to a lesser extent, Aramaic in worship, but later incorporated Arabic in parts of their liturgy.

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

Today, when used in an ecclesiastical sense it typically refers specifically to the Melkite Greek Catholic Church. It can also refer to the church's membership as an ethnoreligious group.[3] The several Greek Orthodox churches formerly known as Melkite are not commonly so called today.

Background

Melkites view themselves as the first Christian community, dating the Melkite Church back to the time of the Apostles.[4] This first community is said to have been a mixed one made up of individuals who were Greek, Roman, Syriac, and Jewish.

Hellenistic Judaism and the Judeo-Greek "wisdom" literature popular in the late Second Temple era amongst both Hellenized Jews (known as Mityavnim) and gentile Greek proselyte converts to Judaism played an important part in the formation of the Melkite tradition.

After the Islamic conquests of the Levant in the 7th century, the Melkite community started incorporating Arabic language in the liturgical traditions as the Middle East became gradually Arabized.[4]

Orthodox Melkites

The term Melkite was originally used as a pejorative term after the acrimonious division that occurred in Eastern Christianity after the Council of Chalcedon (451). It was used by non-Chalcedonians to refer to those who backed the council and the Byzantine Emperor (malko and its cognates are Semitic words for "king"). The Melkites were generally Greek-speaking city-dwellers living in the west of the Levant and in Egypt, as opposed to the more provincial Syriac- and Coptic-speaking non-Chalcedonians. The Melkite Church was organised into three historic patriarchates—Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem—in union with the Patriarch of Constantinople. After the Council of Chalcedon, over the ensuing centuries those Churches which rejected this council recognised different patriarchs in Alexandria (Coptic Orthodox Church) and Antioch (Syriac Orthodox Church). The Nubian kingdom of Makuria (in modern Sudan) in contrast to their Non-Chalcedonian Ethiopian Orthodox neighbours, was also Chalcedonian, from c. 575 until c. 710 and still had a large Melkite minority until the 15th century.

Main Melkite Orthodox Churches are:

- Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria

- Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch

- Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem

Some typically Grecian "Ancient Synagogal" priestly rites and hymns have survived partially to the present, notably in the distinct church services of the Melkite and Greek Orthodox communities of the Hatay Province of Southern Turkey, Syria and Lebanon. Members of these communities still call themselves Rûm which literally means "Roman" in Arabic (that is, those of the (Eastern) Roman Empire, what English speakers often call "Byzantine"). The term "Rûm" is used in preference to "Ionani" or "Yāvāni" which means "Greek" or Ionian in Classical Arabic and Biblical Hebrew.

Catholic Melkites

From 1342, Roman Catholic clergy were based in Damascus and other areas, and worked toward a union between Rome and the Orthodox. At that time, the nature of the East-West Schism, normally dated to 1054, was undefined, and many of those who continued to worship and work within the Melkite Church became identified as a pro-Western party. In 1724, Cyril VI (Seraphim Tanas) was elected in Damascus by the Synod as Patriarch of Antioch. Considering this to be a Catholic takeover attempt, Jeremias III of Constantinople imposed a deacon, the Greek monk Sylvester to rule the patriarchate instead of Cyril. After being ordained a priest, then bishop, he was given Turkish protection to overthrow Cyril. Sylvester's heavy-handed leadership of the church encouraged many to re-examine the validity of Cyril's claim to the patriarchal throne.

The newly elected Pope Benedict XIII (1724–1730) also recognised the legitimacy of Cyril's claim and recognized him and his followers as being in communion with Rome. From that point onwards, the Melkite Church was divided between the Greek Orthodox (Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch), who continued to be appointed by the authority of the Patriarch of Constantinople until the late 19th century, and the Greek Catholics (Melkite Greek Catholic Church), who recognize the authority of the Pope of Rome. However, it is now only the Catholic group who continue to use the title Melkite; thus, in modern usage, the term applies almost exclusively to the Arabic-speaking Greek Catholics from the Middle East.

Notes

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Melchites. |

References

- Meyendorff 1989, p. 190.

- Dick 2004, p. 9.

- Sebastian P. Brock (2006). An introduction to Syriac studies (2, revised, illustrated ed.). Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 9781593333492.

- David Little, Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious Understanding (8 January 2007). Peacemakers in action: profiles of religion in conflict resolution (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780521853583.

References

- Dick, Iganatios (2004). Melkites: Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholics of the Patriarchates of Antioch, Alexandria and Jerusalem. Roslindale, MA: Sophia Press.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.