Adverse possession

Adverse possession, sometimes colloquially described as "squatter's rights",[lower-alpha 1] is a legal principle under which a person who does not have legal title to a piece of property — usually land (real property) — acquires legal ownership based on continuous possession or occupation of the property without the permission of its legal owner.[1]

| Property law |

|---|

| Part of the common law series |

| Types |

| Acquisition |

| Estates in land |

| Conveyancing |

| Future use control |

| Nonpossessory interest |

| Related topics |

| Other common law areas |

|

Higher category: Law and Common law |

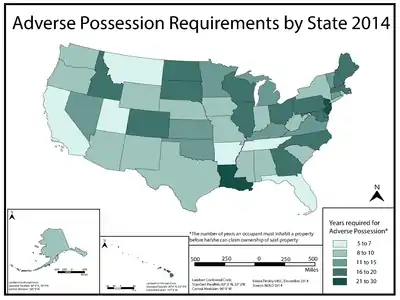

In general, a property owner has the right to recover possession of their property from unauthorised possessors through legal action such as ejectment. However, in the English common law tradition, courts have long ruled that when someone occupies a piece of property without permission and the property's owner does not exercise their right to recover their property for a significant period of time, not only is the original owner prevented from exercising their right to exclude, but an entirely new title to the property "springs up" in the adverse possessor. In effect, the adverse possessor becomes the property's new owner.[2][lower-alpha 2] Over time, legislatures have created statutes of limitations that specify the length of time that owners have to recover possession of their property from adverse possessors. In the United States, for example, these time limits vary widely between individual states, ranging from as low as three years to as long as 40 years.[3]

Although the elements of an adverse possession action are different in every jurisdiction, a person claiming adverse possession is usually required to prove non-permissive use of the property that is actual, open and notorious, exclusive, adverse and continuous for the statutory period.[4][lower-alpha 3]

Personal property, traditionally known as 'chattel', may also be adversely possessed, but owing to the differences in the nature of real and chattel property, the rules governing such claims are rather more stringent, and favour the legal owner rather than the adverse possessor. Claims for adverse possession of chattel often involve works of art.

History

In Roman law, usucapio laws allowed someone who was in possession of a good without title to become the lawful proprietor if the original owner did not appear after some time (one or two years), unless the good was obtained illegally (by theft or force). Stemming from Roman law and its successor, the Napoleonic Code, adopted as the basis of law in France, Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, and also, in part, by the Netherlands and Germany, adverse possession generally recognises two time periods for the acquisition of property: 30 years and some lesser time period, depending on the bona fides of the possessor and the location of the parties involved.

Parliament passed England's first general statute limiting the right to recover possession of land in 1623.[5] At common law, if entitlement to possession of land was in dispute (originally only in what were known as real actions), the person claiming a right to possession was not allowed to allege that the land had come into their possession in the past (in older terminology that he had been 'put into seisin') at a time before the reign of Henry I. The law recognised a cutoff date going back into the past, before which date the law would not be interested. There was no requirement for a defendant to show any form of adverse possession. As time went on, the date was moved by statute—first to the reign of Henry II, and then to the reign of Richard I. No further changes were made of this kind. By the reign of Henry VIII the fact that there had been no changes to the cutoff date had become very inconvenient. A new approach was taken whereby the person claiming possession had to show possession of the land for a continuous period, a certain number of years (60, 50 or 30 depending on the kind of claim made) before the date of the claim. Later statutes have shortened the limitation period in most common law jurisdictions.

At traditional English common law, it was not possible to obtain title to property of the Crown by means of adverse possession. This principle was embodied by the Latin maxim nullum tempus occurrit regi ('no time runs against the king'). In the United States, this privilege was carried over to the federal and state governments; government land is immune from loss by adverse possession.[6] Land with registered title in some Torrens title systems is also immune, for example, land that has been registered in the Hawaii Land Court system.[7][8]

In the common law system of England and its historical colonies, local legislatures—such as Parliament in England or American state legislatures—generally create statutes of limitations that bar the owners from recovering the property after a certain number of years have passed.[3]

England and Wales

Adverse possession is one of the most contentious methods of acquiring property, albeit one that has played a huge role in the history of English land. Historically, if someone possessed land for long enough, it was thought that this in itself justified acquisition of a good title. This meant that while English land was continually conquered, pillaged, and stolen by various factions, lords or barons throughout the Middle Ages, those who could show they possessed land long enough would not have their title questioned.

A more modern function has been that land which is disused or neglected by an owner may be converted into another's property if continual use is made. Squatting in England has been a way for land to be efficiently utilised, particularly in periods of economic decline. Before the Land Registration Act 2002, if a person had possessed land for 12 years, then at common law, the previous owner's right of action to eject the "adverse possessor" would expire. The common legal justification was that under the Limitation Act 1623, just like a cause of action in contract or tort had to be used within a time limit, so did an action to recover land. This promoted the finality of litigation and the certainty of claims.[9] Time would start running when someone took exclusive possession of land, or part of it, and intended to possess it adversely to the interests of the current owner. Provided the common law requirements of "possession" that was "adverse" were fulfilled, after 12 years, the owner would cease to be able to assert a claim. Different rules are in place for the limitation periods of adverse possession in unregistered land[10] and registered land.[11] However, in the Land Registration Act 2002 adverse possession of registered land became much harder.

In recent times the Land Registry has made the process of claiming Adverse Possession and being awarded “title absolute” more difficult. Simply occupying or grazing the land will no longer justify the grant of title, instead the person in adverse possession must demonstrate commitment to own and utilise to the exclusion of all other the land intended to be claimed.

Land Registration Act 2002

This legislation received Royal Assent on the 26th of February 2002.[12] The rules for unregistered land remained as before. But under the LRA 2002 Schedule 6, paragraphs 1 to 5, after 10 years the adverse possessor is entitled to apply to the registrar to become the new registered owner. The registrar then contacts the registered title holder and notifies him of the application. If no proceedings are launched for two years to eject the adverse possessor, only then would the registrar transfer title. Prior to the 2002 Act, a land owner could simply lose title without being aware of it or notified. This was the rule because it indicated the owner had never paid sufficient attention to how the land was in fact being used, and therefore the former owner did not deserve to keep it. Before 2002, time was seen to cure everything. The rule's function was to ensure land was used efficiently.[13]

Requirements

Before the considerable hurdle of giving a registered owner notice was introduced in the LRA 2002, the particular requirements of adverse possession were reasonably straight forward. First, under Schedule 1, paragraphs 1 and 8 of the Limitation Act 1980, the time when adverse possession began was when "possession" was taken. This had to be more than something temporary or transitory, such as simply storing goods on a land for a brief period.[14] But "possession" did not require actual occupation. So in Powell v McFarlane,[15] it was held to be "possession" when Mr Powell, from age 14, let his cows roam into Mr McFarlane's land. The second requirement, however, was that there needed to be an intention to possess the land. Mr Powell lost his claim because simply letting his cows roam was an equivocal act: it was only later that there was evidence he intended to take possession, for instance by erecting signs on the land and parking a lorry. But this had not happened long enough for the 12-year time limit on McFarlane's claim to have expired. Third, possession is not considered "adverse" if the person is there with the owner's consent. For example, in BP Properties Ltd v Buckler, Dillon LJ held that Mrs Buckler could not claim adverse possession over land owned by BP because BP had told her she could stay rent free for life.[16] Fourth, under the Limitation Act 1980 sections 29 and 30, the adverse possessor must not have acknowledged the title of the owner in any express way, or the clock starts running again. However, the courts have interpreted this requirement flexibly.

Human Rights challenges

In JA Pye (Oxford) Ltd v Graham, Mr and Mrs Graham had been let a part of Mr Pye's land, and then the lease had expired. Mr Pye refused to renew a lease, on the basis that this might disturb getting planning permission. In fact the land remained unused, Mr Pye did nothing, while the Grahams continued to retain a key to the property and used it as part of their farm. At the end of the limitation period, they claimed the land was theirs. They had in fact offered to buy a licence from Mr Pye, but the House of Lords held that this did not amount to an acknowledgement of title that would deprive them of a claim. Having lost in the UK courts, Mr Pye took the case to the European Court of Human Rights, arguing that his business should receive £10 million in compensation because it was a breach of his right under ECHR Protocol 1, article 1 to "peaceful enjoyment of possessions".[17] The Court rejected this, holding that it was within a member state's margin of appreciation to determine the relevant property rules.[18] Ofulue v Bossert[19] confirmed this. Otherwise, a significant limit on the principle in the case of leases is that adverse possession actions will only succeed against the leaseholder, and not the freeholder once the lease has expired.[20] However the main limitation remains that the 2002 legislation appears to have emasculated the principle of adverse possession, because the Registrar now effectively informs owners of the steps to be taken to prevent adverse possession.

Timing

For registered land, adverse possession claims completed before 13 October 2003 (the date the 2002 Act came into force)[21] are governed by section 75(1) and 75(2) of the Land Registration Act of 1925. The limitation period remains the same (12 years) but instead of the original owner's title to the land being extinguished, the original owner holds the land on trust for the adverse possessor.[22] The adverse possessor can then apply to be the new registered proprietor of the land.[23]

For registered land, adverse possession claims completed after 13 October 2003 follow a different procedure. Where land is registered, the adverse possessor may henceforth apply to be registered as owner after 10 years[24] of adverse possession and the Land Registry must give notice to the true owner of this application.[25] This gives the landowner a statutory period of time [65 business days] to object to the adverse possession, object to the application on the ground that there has not actually been the necessary 10 years' adverse possession, and/or to serve a "counter-notice". If a counter-notice is served, then the application fails unless

- it would be unconscionable because of an equity by estoppel for the registered proprietor to seek to dispossess the squatter and the squatter ought in the circumstances to be registered as proprietor, or

- the squatter is for some other reason entitled to be registered as proprietor, or

- the squatter has been in adverse possession of land adjacent to their own under the mistaken but reasonable belief that they are the owner of it, the exact line of the boundary with this adjacent land has not been determined and the estate to which the application relates was registered more than a year prior to the date of the application.

Otherwise, the squatter becomes the registered proprietor according to the land registry. If the true owner is unable to evict the squatter in the two years following the first [unsuccessful] application, the squatter can apply again after this period and be successful despite the opposition of the owner. The process effectively prevents the removal of a landowner's right to property without their knowledge, while ensuring squatters have a fair way of exercising their rights.

Where a tenant adversely possesses land, there is a presumption that they are doing so in a way that will benefit the landlord at the end of their term. If the land does not belong to their landlord, the land will become part of both the tenancy and the reversion. If the land does belong to their landlord, it would seem that it will be gained by the tenant but only for the period of their term.[26]

Since September 2012, squatting in a residential building is a criminal offence, but this does not prevent title being claimed by reason of adverse possession even if the claimant is committing a criminal offence.[27][28] This was confirmed in Best v Chief Land Registrar,[29] where it was held that criminal and land law should be kept separate.

United States

Requirements

The party seeking title by adverse possession may be called the disseisor, meaning one who dispossesses the true owner of the property.[30] Although the elements of an adverse possession claim may be different in a number of states, adverse possession requires at a minimum five basic conditions being met to perfect the title of the disseisor. These are that the disseisor must openly occupy the property exclusively, in a manner that is open and notorious, continuously, and use it as if it were their own in a manner expected for the type of property.[31] Some states impose additional requirements. Many of the states have enacted statutes regulating the rules of adverse possession.[32] Some states require a hostility requirement to secure adverse possession. While most states take an objective approach to the hostility requirement, some states require a showing of good faith. Good faith means that claimants must demonstrate that they had some basis to believe that they actually owned the property at issue. Four states east of the Mississippi that require good faith in some form are Georgia, Illinois, New York, and Wisconsin.[32]

Actual possession

The disseisor must physically use the land as a property owner would, in accordance with the type of property, location, and uses (merely walking or hunting on land does not establish actual possession). The actions of the disseisor must change the state of the land (in the case of non-residential property, taking such actions as clearing, mowing, planting, harvesting fruit of the land, logging or cutting timber, mining, fencing, pulling tree stumps, running livestock and constructing buildings or other improvements) or, if the property is residential, maintaining the property for its intended use (taking such actions as mowing the yard, trimming trees and hedges, changing locks, repairing or replacing fixtures such as a swimming pool, sprinkler system, or appliances), all to the exclusion of its true owner.

In Cone v. West Virginia Pulp & Paper, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit held that Cone failed to establish actual possession by occasionally visiting the land and hunting on it, because his actions did not change the land from a wild and natural state.

Hostile possession

The disseisor must have entered or used the land without permission from the true owner. The disseisor's motivations may be interpreted by the court in several ways, depending upon state law and precedent:

- Objective view – the land was used without true owner's permission and in a manner inconsistent with true owner's rights;

- Bad faith or intentional trespass view – the land was used with the adverse possessor's subjective intent to disregard or violate the actual property owner's rights;

- Good faith view – a few states require that the party claiming adverse possession must have mistakenly believed that it is their land.

Some jurisdictions permit accidental adverse possession, as might occur as the result of a surveying error that places the boundary line between properties in the wrong location.

Renters, hunters or others who enter the land with permission are not taking possession that is hostile to the title owner's rights. (mistaken possession in some jurisdictions does not constitute hostility)

Open and notorious use

The disseisor must possess the property in a manner that is capable of being seen. That is, the disseisor's use of the property must be sufficiently visible and apparent that it gives notice to the legal owner that someone may assert claim, and must be of such character that would give notice to a reasonable person. If legal owner has actual knowledge of the use, this element is met; it can be also met by fencing, opening or closing gates or an entry to the property, posted signs, crops, buildings, or animals that a diligent owner could be expected to know about.

Continuous use

The disseisor claiming adverse possession must hold that property continuously for the entire statute of limitations period, and use it as a true owner would for that time.

Generally, the disseisor's openly hostile possession must be continual (although not necessarily constant) without challenge or permission from the lawful owner, but breaks in use that are consistent with how an owner would use the property will not prevent an adverse possession claim. Occasional activity on the land with long gaps in activity fail the test of continuous possession; courts have ruled that merely cutting timber at intervals, when not accompanied by other actions that demonstrate actual and continuous possession, fails to demonstrate continuous possession. If at any time during the statute of limitations period, the true owner ejects the disseisor from the land either verbally or through legal action, and the disseisor then returns and dispossesses him again, then the statute of limitations period begins anew.

The statute of limitations applies only to the disseisor's time on the property, not how long the true owner may have been dispossessed of it (by, say, another disseisor who then left the property). However, if adverse possession is continuous between two or more successive disseisors without interruption, it may be possible for the second disseisor to claim adverse possession for the entire period based upon a legal doctrine known as tacking.

Exclusive use

The disseisor holds the land to the exclusion of the true owner. There may be more than one adverse possessor, taking as tenants in common, so long as the other elements are met. Adverse possession claims may potentially be defeated by the title owner's use of the land during the statutory period.

Additional requirements

In addition to the basic elements of an adverse possession case, state law may require one or more additional elements to be proved by a person claiming adverse possession. Depending upon the state, additional requirements may include:

- Color of title, claim of title, or claim of right. Color of title and claim of title involve a legal document that appears (incorrectly) to give the disseisor title.[33] In some jurisdictions the mere intent to take the land as one's own may constitute "claim of right", with no documentation required. Other cases have determined that a claim of right exists if the person believes they have rightful claim to the property, even if that belief is mistaken.[34] A negative example would be a timber thief who sneaks onto a property, cuts timber not visible from the road, and hauls the logs away at night. Their actions, though they demonstrate actual possession, also demonstrate knowledge of guilt, as opposed to claim of right.

- Good faith (in a minority of states) or bad faith (sometimes called the "Maine Doctrine" although it is now abolished in Maine)[35]

- Improvement, cultivation, or enclosure[33][36]

- Payment of property taxes. This may be required by statute, such as in California,[37] or just a contributing element to a court's determination of possession. Both payment by the disseisor and by the true owner are relevant.

- Dispossession of land owned by a governmental entity: Generally, a disseisor cannot dispossess land legally owned by a government entity even if all other elements of adverse possession are met. One exception is when the government entity is acting like a business rather than a government entity.[30]

Consequences

A disseisor will be committing a civil trespass on the property he has taken and the owner of the property could cause him to be evicted by an action in trespass ("ejectment") or by bringing an action for possession. All common law jurisdictions require that an ejectment action be brought within a specified time, after which the true owner is assumed to have acquiesced. The effect of a failure by the true landowner to evict the adverse possessor depends on the jurisdiction, but will eventually result in title by adverse possession.

In 2008, due to the volume of adverse possession and boundary dispute cases throughout New York City, the New York State Legislature amended and limited the ability of land to be acquired by adverse possession.[40] Prior to the 2008 amendment, to acquire property by adverse possession, all that was required was a showing that the possession constituted an actual invasion of or infringement upon the owner's rights.[41] Approximately eight (8) years after the 2008 amendment, on 30 June 2016, the New York State Appellate Division, First Department (i.e., the appellate court covering the territory of Manhattan) determined the legal questions concerning the scope of rights acquired by adverse possession and how the First Department would treat claims of adverse possession where title had vested prior to 2008.[42] The Court specifically held that title to the adversely possessed property vested when the plaintiff "[S]atisfie[d] the requirement of the statute in effect at the relevant time."[42] In other words, if title had vested at some time "after" the 2008 amendment, a plaintiff would have to satisfy the adverse possession standards amended by the New York State Legislature in 2008; however, if title vested at some time "before" the 2008 amendment, a plaintiff would have lawfully acquired title to the disputed area by satisfying the pre-amendment standard for adverse possession. Hudson Square Hotel also resolved two often highly litigated issues in adverse possession cases where the air rights are more valuable than the underlying land itself: (a) "where" (i.e., in three-dimensional physical space) is an encroachment required in order for such encroachment to have any relevant operative effect or consequences under the law of adverse possession, and (b) "what" property rights are acquired as a result of title to the ground floor area (i.e., the land) vesting with the plaintiff. In Hudson Square Hotel the defendant argued that the plaintiff had only acquired title to the underlying land, but not the air rights, because the plaintiff never encroached above the two-story building. This argument was motivated, in part, by the fact that the zoning laws at the time permitted the owner of the land to build (i.e., develop) up to six (6) times the square footage of the ground floor area. For example, if the disputed area was 1,000 square feet, there would be 6,000 square feet of buildable square footage to potentially be won or lost by adverse possession. The Court clarified, "It is the encroachment on the land ... that allows title to pass to the adverse possessor."[42] In other words, the plaintiff did not need to encroach upon all six stories in order to adversely possess the air rights above the land. The Court also held, "With title to land come air rights."[42] In other words, by acquiring title to the land (i.e., ground floor area), the plaintiff also acquired ownership of the more valuable air rights that were derivative of title to the underlying land.

In other jurisdictions, the disseisor acquires merely an equitable title; the landowner is considered to be a trustee of the property for the disseisor.

Adverse possession extends only to the property actually possessed. If the original owner had a title to a greater area (or volume) of property, the disseisor does not obtain all of it. The exception to this is when the disseisor enters the land under a color of title to an entire parcel, their continuous and actual possession of a small part of that parcel will perfect their title to the entire parcel defined in their color of title. Thus a disseisor need not build a dwelling on, or farm on, every portion of a large tract in order to prove possession, as long as their title does correctly describe the entire parcel.

In some jurisdictions, a person who has successfully obtained title to property by adverse possession may (optionally) bring an action in land court to "quiet title" of record in their name on some or all of the former owner's property. Such action will make it simpler to convey the interest to others in a definitive manner, and also serves as notice that there is a new owner of record, which may be a prerequisite to benefits such as equity loans or judicial standing as an abutter. Even if such action is not taken, the title is legally considered to belong to the new titleholder, with most of the benefits and duties, including paying property taxes to avoid losing title to the tax collector. The effects of having a stranger to the title paying taxes on property may vary from one jurisdiction to another. (Many jurisdictions have accepted tax payment for the same parcel from two different parties without raising an objection or notifying either party that the other had also paid.)

Adverse possession does not typically work against property owned by the public.

The process of adverse possession would require a thorough analysis if private property is taken by eminent domain, after which control is given to a private corporation (such as a railroad), and then abandoned.

Where land is registered under a Torrens title registration system or similar, special rules apply. It may be that the land cannot be affected by adverse possession (as was the case in England and Wales from 1875 to 1926, and as is still the case in the state of Minnesota[43]) or that special rules apply.

Adverse possession may also apply to territorial rights. In the United States, Georgia lost an island in the Savannah River to South Carolina in 1990, when South Carolina had used fill from dredging to attach the island to its own shore. Since Georgia knew of this yet did nothing about it, the U.S. Supreme Court (which has original jurisdiction in such matters) granted this land to South Carolina, although the Treaty of Beaufort (1787) explicitly specified that the river's islands belonged to Georgia.[44]

Civil law states

Some non-common law jurisdictions have laws similar to adverse possession. For example, Louisiana has a legal doctrine called acquisitive prescription, which is derived from French law.

Squatter's rights

Most cases of adverse possession deal with boundary line disputes between two parties who hold clear title to their property. The term "squatter's rights" has no precise and fixed legal meaning. In some jurisdictions the term refers to temporary rights available to squatters that prevent them, in some circumstances, from being removed from property without due process. For example, in England and Wales reference is usually to section 6 of the Criminal Law Act 1977. In the United States, no ownership rights are created by mere possession, and a squatter may only take possession through adverse possession if the squatter can prove all elements of an adverse possession claim for the jurisdiction in which the property is located.[45]

As with any adverse possession claim, if a squatter abandons the property for a period, or if the rightful owner effectively removes the squatter's access even temporarily during the statutory period, or gives their permission, the "clock" usually stops. For example, if the required period in a given jurisdiction is twenty years and the squatter is removed after only 15 years, the squatter loses the benefit of that 15-year possession (i.e., the clock is reset at zero). If that squatter later retakes possession of the property, that squatter must, to acquire title, remain on the property for a full 20 years after the date on which the squatter retook possession. In this example, the squatter would have held the property for a total of 35 years (the original 15 years plus the later 20 years) to acquire title.

Depending on the jurisdiction, one squatter may or may not pass along continuous possession to another squatter, known as "tacking". Tacking is defined as "The joining of consecutive periods of possession by different persons to treat the periods as one continuous period; esp., the adding of one's own period of land possession to that of a prior possessor to establish continuous adverse possession for the statutory period."[46] There are three types of Privity: Privity of Contract; Privity of Possession; and Privity of Estate.[46] One of the three types of privity is required in order for one adverse possessor to "tack" their time onto another adverse possessor in order to complete the statutory time period. One way tacking occurs is when the conveyance of the property from one adverse possessor to another is founded upon a written document (usually an erroneous deed), indicating "color of title." A lawful owner may also restart the clock at zero by giving temporary permission for the occupation of the property, thus defeating the necessary "continuous and hostile" element. Evidence that a squatter paid rent to the owner would defeat adverse possession for that period.

England and Wales

'Squatting' became a criminal offence in England/Wales under Section 144 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012.[47]

This section also inserted an immediate power of entry to the premises into Section 17 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984.

United States

In the United States, the concept of squatter's rights is generally used to refer to a specific form of adverse possession where the disseisor holds no title to any properties adjoining the property under dispute. In most jurisdictions of the United States, few squatters can meet the legal requirements for adverse possession.

Comparison to homesteading

Adverse possession is in some ways similar to homesteading. Like the disseisor, the homesteader may gain title to property by using the land and fulfilling certain other conditions. In homesteading, however, the possession of the property is not hostile; the land is either considered to have no legal owner or is owned by the government. The government allows the homesteader to use the land with the expectation that the homesteader who fulfills the requirements necessary for the homestead will gain title to the property.

The principles of homesteading and squatter's rights embody the most basic concept of property and ownership, which can be summarized by the adage "possession is nine-tenths of the law," meaning the person who uses the property effectively owns it. Likewise, the adage, "use it or lose it," applies. The principles of homesteading and squatter's rights predate formal property laws; to a large degree, modern property law formalizes and expands these simple ideas.

The principle of homesteading is that if no one is using or possessing property, the first person to claim it and use it consistently over a specified period owns the property. Squatter's rights embodies the idea that if one property owner neglects property and fails to use it, and a second person starts to tend and use the property, then after a certain period the first person's claim to the property is lost and ownership transfers to the second person, who is actually using the property.

The legal principle of homesteading, then, is a formalization of the homestead principle in the same way that the right of adverse possession is a formalization of the pre-existing principle of squatter's rights.

The essential ideas behind the principles of homesteading and squatter's rights hold generally for any type of item or property of which ownership can be asserted by simple use or possession. In modern law, homesteading and the right of adverse possession refer exclusively to real property. In the realm of personal property, the same impulse is summarized by the adage "finders, keepers" and is formalized by laws and conventions concerning abandoned property.

Adverse possession of easements

Some jurisdictions merge the concept of adverse possession with that of prescription, so that adverse possession may be used to gain various incorporeal rights to land as well as land itself.

Under this theory, adverse possession grants only those rights in the disseized property that are 'taken' by the disseisor. For example, a disseisor might choose to take an easement rather than the entire fee title to the property. In this manner, it is possible to disseize an easement, under the legal doctrine of prescription. This must also be done openly but need not be exclusive. Prescription is governed by different statutory and common law time limits to adverse possession. It is common practice in cities such as New York, where builders often leave sidewalk space or plazas in front of their buildings to meet zoning requirements, to close public areas they own periodically to prevent the creation of a permanent easement that would cloud their exclusive property rights. For the same reason, city sidewalks may have embedded markers along the property line around a plaza or open area announcing "This Space Not Dedicated" to indicate that although the public may use the space within the markers, it is still private property.

If a property owner interferes with an easement upon their property in a manner that satisfies the requirements for adverse prescription (e.g. locking the gates to a commonly used area, and nobody does anything about it), he will successfully extinguish the easement. This is another reason to quiet title after a successful adverse possession or adverse prescription: it clarifies the record of who should take action to preserve the adverse title or easement while evidence is still fresh.

For example, given a deeded easement to use someone else's driveway to reach a garage, if a fence or permanently locked gate prevents the use, nothing is done to remove and circumvent the obstacle, and the statutory period expires, then the easement ceases to have any legal force, although the deed held by the fee-simple owner stated that the owner's interest was subject to the easement.

Strictly speaking, prescription works in a different way to adverse possession. Adverse possession is concerned with the extinction of the title of the original owner by a rule of limitation of actions. Prescription, on the other hand, is concerned with acquiring a right that did not previously exist.

In the law of England and Wales, adverse possession and prescription are treated as being entirely different doctrines. The former being entirely statutory deriving from the Limitation Act 1980, the latter being possible under purely common law principles.

Theory and scholarship

Utilitarianism

Scholars have identified four utilitarian policies which justify adverse possession. The first is that it exists to cure potential or actual defects in real estate titles by putting a statute of limitations on possible litigation over ownership and possession. Because of the doctrine of adverse possession, a landowner can be secure in title to their land. Otherwise, long-lost heirs of any former owner, possessor or lien holder of centuries past could come forward with a legal claim on the property. The second theory is that adverse possession is "a useful method for curing minor title defects".[48] For example, someone may have had the intention to sell all of a parcel of land but mistakenly excluded a portion of it on the title. Thus, adverse possession allows the purchaser of the land to maintain ownership of the parcel which they believed was theirs from the impressions given by the seller. The third theory is that adverse possession encourages and rewards productive use of land. Essentially, "by vesting title in the industrious settler -rather than the absentee landowner- adverse possession promote[s] rapid development". The fourth and final theory is that the adverse possessor places a high personal value on the land while the real title holder has effectively abandoned it, thus on principles of personhood and efficiency it makes sense to allow the change in title.[48]

Copyright scholarship

Some legal scholars have proposed the extension of the concept of adverse possession to intellectual property law, in particular to reconcile intellectual property and antitrust law[49] or to unify copyright law and property law.[50]

See also

- Appropriation (economics)

- Informal settlement

- Title (property)

- Pedis possessio ("possession of the foot"): ownership by first occupier

- Squatting: unauthorized use of abandoned property with no implied ownership or right to use

- Usucaption: acquisitive prescription ownership after defined period of unauthorized occupation

- Uti possidetis

- Preemption Act of 1841: acquisitive prescription law in USA

- Rights of way in England and Wales

- Usufruct: acquired right to use but not own property

- Revised statute 2477: highways & paths law in USA

- Easement: for related adverse rights

- Lien: right of others to hold or sell to solve debt

- List of real estate topics

- Possession is nine-tenths of the law

- Property law

- Property rights

- Deed: legal document defining interest or ownership

- Adverse abandonment

References

Notes

- Squatting refers specifically to land ("real property") and is by far the most common form of adverse possession. Some jurisdictions have additional differences between "squatting" and adverse possession.

- As described in the various "Requirements" sections, a number of conditions must be met in order for the adverse possessor to actually acquire title.

- Adverse possession is a method of acquiring complete title to land as against all others, including the record owner, through certain acts over an uninterrupted period of time, as prescribed by statute. Gifis, Steven H. (1984) Barron's Law Dictionary, page 14; "An open, notorious, exclusive and adverse possession for twenty years operates to convey a complete title...not only an interest in the land...but complete dominion over it." Sir William Blackstone (1759) Commentaries on the Laws of England, Volume 2, page 418.

Citations

- "Adverse possession". Wex. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Merrill & Smith (2016), p. 161.

- Merrill & Smith (2016), p. 170.

- Black, Henry T. (1979). Black's Law Dictionary, 5th ed. St. Paul: West Publishing Co. p. 49. ISBN 0829920455.

- Merrill (1985), p. 1128.

- Merrill & Smith (2016), p. 174.

- "HI Rev Stat § 501-87". Hawaii Revised Statutes. Hawaii State Legislature. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- United States v. Fullard-Leo, 66 F.Supp. 782 (D.C. Haw. 1944), affirmed 331 U.S. 256 (1947).

- Law Reform Committee, 21st Report, Final Report on Limitation of Actions (1977) Cmnd 6923, para 1.7.

- Limitation Act 1980 ss 15 and 17.

- Land Registration Act 1925 s 75 or Land Registration Act 2002 Sch 6, depending on when the limitation period is completed.

- Explanatory Notes to the Land Registration Act 2002, para. 1

- See generally JE Stake, 'The Uneasy Case for Adverse Possession' (2000–2001) 89 Georgetown Law Journal 2419.

- e.g. Leigh v Jack (1879) 5 Ex D 264.

- (1979) 38 P&CR 352.

- (1988) 55 P&CR 337.

- The point has been made by O Jones, Out with the Owners: The Eurasian Sequels to "J A Pye (Oxford) Ltd v. United Kingdom" (2008) 27 Civil Justice Quarterly 260–276, that adverse possession should be incapable of infringing the ECHR's concept of the right to property precisely because the person deprived has given up "possession".

- [2008] 1 EHRLR 132.

- "Ofulue & Anor v Bossert [2009] UKHL 16 (11 March 2009)". www.bailii.org. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- Fairweather v St Marylebone Property Co Ltd [1963] AC 510.

- Section 1 The Land Registration Act 2002 (Transitional Provisions) (No 2) Order 2003).

- Section 75(1) Land Registration Act 1925.

- Section 75(2) Land Registration Act 1925.

- Schedule 6 Paragraph 1 Land Registration Act 2002.

- Schedule 6 Paragraph 2 Land Registration Act 2002.

- Smirk v Lyndale Developments Ltd [1974] 3 WLR 91.

- Blake, Joseph (31 August 2012). "Criminalising squatting hurts the poor and benefits the rich". The Guardian.

- "Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012". The National Archives.

- "Best v The Chief Land Registrar & Anor [2014] EWHC 1370 (Admin) (07 May 2014)". www.bailii.org. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- "Adverse possession". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Larson, Aaron (17 January 2015). "Adverse Possession". Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "Analyzing Adverse Possession Laws and Cases of the States East of the Mississippi River". American Land Title Association. 1 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "California Code of Civil Procedure § 323". California Legislative Information. California Office of Legislative Counsel. 1872. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- See, e.g., "North American Oil Consol. v. Burnet, 286 US 417 (1932)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "Dombkowski v. Ferland, 2006 ME 24, 893 A.2d 599 (2006)". Google Scholar. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "California Code of Civil Procedure § 325". California Legislative Information. California Office of Legislative Counsel. 9 July 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- California Code of Civil Procedure Section 325.

- Jordan, Cora; Randolph, Mary (1994). "Easements Acquired by Use of Property" (PDF). Neighbor law : fences, trees, boundaries, and noise (2nd ed.). Berkeley: Nolo Press. ISBN 9780873372664. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- Dunlap, David W. (30 October 2011). "Lever House Closes Once a Year to Maintain Its Ownership Rights". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Mavidis, Andriana (Summer 2011). "Retrospective Application of the 2008 Amendments to New York's Adverse Possession Laws". St. John's Law Review. 85 (3): 1057–1103.

- "Bayshore Gardens Owners, Inc. v Meersand 2008 NY Slip Op 51770(U) [20 Misc 3d 1137(A)] Decided on August 18, 2008". Google Scholar. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "Hudson Sq. Hotel, LLC v Stathis Enters., LLC 2016 NY Slip Op 05232". New York State Law Reporting Bureau. 30 June 2016.

- Minn. Stat. 508.02.

- Georgia v. South Carolina, 497 U.S. 376 (1990) see Georgia v. South Carolina.

- Estrin, Michael (27 July 2012). "Adverse possession: Can you squat to own?". BankRate. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- TACKING, Black's Law Dictionary (10th ed. 2014)

- "Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Sprankling, John G. (2017). Understanding property law (Fourth ed.). Durham, North Carolina: Carolina Academies Press. pp. 480–481. ISBN 978-1-5221-0557-2. OCLC 960940360.

- Constance E. Bagley and Gavin Clarkson, "Adverse Possession for Intellectual Property: Adapting an Ancient Concept to Resolve Conflicts between Antitrust and Intellectual Property Laws in the Information Age" Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 16:2 (Spring 2003) full text.

- Michael James Arrett, "Adverse Possession of Copyright: A Proposal to Complete Copyright's Unification with Property Law", Journal of Corporation Law 31:1 (October 2005) abstract; full text (pay).

Works cited

- Merrill, Thomas W. (1985). "Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Adverse Possession". Northwestern University Law Review. 79 (5 & 6): 1122–54.

- Merrill, Thomas W.; Smith, Henry E. (2017). Property: Principles and Policies. University Casebook Series (3rd ed.). St. Paul: Foundation Press. ISBN 978-1-62810-102-7.

Further reading

- O Jones, 'Out with the Owners: The Eurasian Sequels to J A Pye (Oxford) Ltd v. United Kingdom' (2008) 27 Civil Justice Quarterly 260–276