Afrin District

Afrin District (Arabic: منطقة عفرين, romanized: manṭiqat Afrīn) is a district of Aleppo Governorate in northern Syria. The administrative centre is the city of Afrin. At the 2004 census, the district had a population of 172,095.[1] Syria's Afrin District fell under the control of the People's Protection Units (YPG) around 2012 and an "Afrin Canton" was declared in 2014, followed by an "Afrin Region" in 2017. During Operation Olive Branch, the entire district was captured by Turkey and its allies.[2]

Afrin District

منطقة عفرين | |

|---|---|

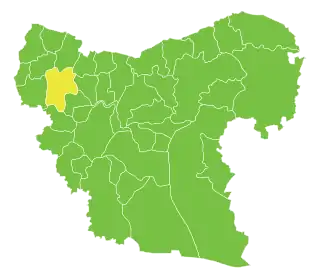

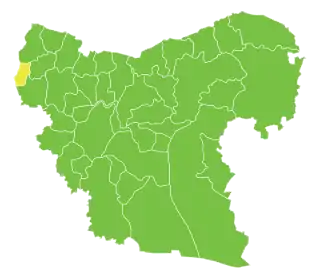

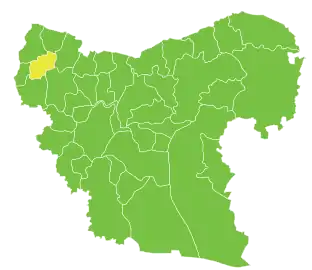

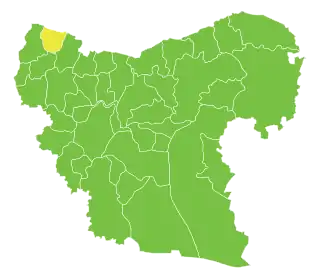

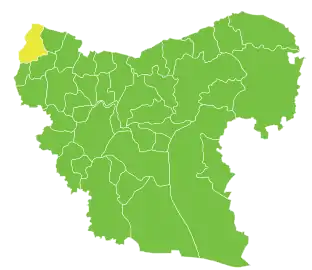

Location of Afrin District within Aleppo Governorate | |

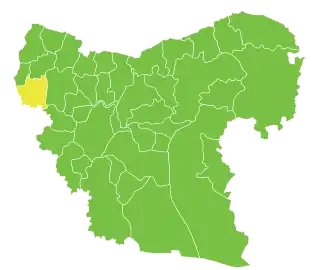

Afrin District Location in Syria | |

| Coordinates (Afrin): 36.51°N 36.8678°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aleppo |

| Seat | Afrin |

| Control | |

| Subdistricts | 7 nawāḥī |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,840.85 km2 (710.76 sq mi) |

| Population (2004)[1] | 172,095 |

| Geocode | SY0203 |

History

According to René Dussaud, the area of Kurd-Dagh and the plain near Antioch were settled by Kurds since antiquity.[3][4] Stefan Sperl says that there is reason to believe that Kurdish settlements in the Kurd Mountains go back to the Seleucid Empire, since those regions stood in the path to Antioch; Kurds in the early periods served as mercenaries and mounted archers.[5] In any case, the Kurd Mountains were already Kurdish-inhabited when the Crusades broke out at the end of the 11th century.[6]

The area around Afrin developed as the center of a distinctive Sufi "Kurdish Islam".[7] In modern post-independence Syria, the Kurdish society of the district was subject to heavy-handed Arabization policies by the Damascus government.[8]

Syrian civil war

In the course of the Syrian civil war, Damascus government forces pulled back from the district in spring 2012 to give way to the People's Protection Units (YPG) and autonomous self-governemnt under the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, which was formally declared on 29 January 2014.[9] Until 2018, violence in Afrin was minor, involving artillery shelling by Islamist rebel groups[10] as well as by Islamist-governed Turkey.[11][9][12][13]

Afrin was captured by the Turkish Land Forces and Syrian National Army (SNA) as a result of the 2018 Afrin offensive. Tens of thousands of Kurdish refugees fled from Afrin City before its capture by the SNA in March 2018,[14][15] and the YPG vowed to retake it. The YPG subsequently announced its intention to start a guerrilla war in Afrin,[16][17] leading to the SDF insurgency in Northern Aleppo.

Ethnic cleansing

After the Turkish-led forces had captured Afrin in early 2018, they began to implement a resettlement policy by moving their mostly Arab fighters[18] and refugees from southern Syria[19] into the empty homes that belonged to displaced locals.[20] The previous owners, most of them Kurds or Yazidis, were often prevented from returning to Afrin.[18][19] Though some Kurdish militias of the SNA and the Turkish-backed civilian councils opposed these resettlement policies, most SNA units fully supported them.[19] Refugees from Eastern Ghouta, Damascus, said that they were part of "an organised demographic change" which was said to replace the Kurdish population of Afrin with an Arab majority.[18]

Kidnapping of women

Over 150 Yazidi and other Kurdish women and girls have been kidnapped by the SNA since the occupation of Afrin began in early 2018, either for ransom, rape, forced marriage, or because of perceived links to the Democratic Union Party.[21][22][23] Many of them were later killed.[24][25] This activity has been interpreted as part of an Islamist policy of discouraging women from leaving their homes and to remove them from the civic activity they had been encouraged to take part in under the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria,[26] as well as part of a broader plan to discourage the return of Yazidi and other Kurdish refugees who fled Afrin in 2018.[27][28]

Demographics

In the 1930s, Kurdish Alevis who fled the persecution of the Turkish Army during the Dersim Massacre, settled in Maabatli in the Afrin District.[29] Prior to the Syrian Civil War, the population of the Afrin District area was overwhelmingly ethnic Kurdish, to the degree that the district had been described as "homogeneously Kurdish".[30] The overall population of Afrin Canton, based on the 2004 Syrian census, was about 200,000.[31]

Cities and towns with more than 10.000 inhabitants according to the 2004 Syrian census are Afrin (36,562) and Jandairis (13,661).

Throughout the course of the Syrian Civil War, the Afrin District served as a safe haven for inbound refugees of all ethnicities, fleeing violence and destruction from civil war factions, in particular the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and the diverse more or less Islamist rebel groups of the Syrian opposition.[32][33] According to a June 2016 estimate from the International Middle East Peace Research Center, about 316,000 displaced Syrians of Kurdish, Yazidi, Arab and Turkmen ethnicity lived in Afrin Canton at the time.[34]

Economy

A diverse agricultural production was at the heart of the Afrin District's economy,[35] traditionally olives in particular, and more recently there was a focus on increasing wheat production.[36] A well-known product from the area is Aleppo soap, a hard soap made from olive oil and lye, distinguished by the inclusion of laurel oil. While the Afrin District has been the source of olive oil for Aleppo soap since antiquity, the destruction caused by the Syrian Civil War to other parts of Aleppo governorate increasingly made the entire production chains locate in Afrin District.[37][38] At the height of the fighting for Aleppo, up to 50 percent of the city's industrial production was moved to the Afrin District.[39] As of early 2016, two million pairs of jeans were produced per month and exported across Syria.[39] In January 2017, 400 textile industry workshops counted 17,000 employees, supplying the whole of Syria.[40]

In 2015 there were 32 tons of Aleppo soap produced and exported to other parts of Syria, but also to international markets.[39]

Tourism

Afrin District also served as a center for domestic tourism due to its beautiful landscapes. The tourism was however somewhat constricted due to the YPG's tight control of the borders, and the war; local tourism mostly collapsed during the Turkish invasion of 2018.[41]

Subdistricts

The district of Afrin is divided into seven subdistricts or nawāḥī (population as of 2004[1]):

| Code | Name | Area | Population | Seat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SY020300 | Afrin Subdistrict | 427.73 km² | 66,188 | Afrin |

| SY020301 | Bulbul Subdistrict | 203.36 km² | 12,573 | Bulbul |

| SY020302 | Jindires Subdistrict | 319.43 km² | 32,947 | Jindires |

| SY020303 | Rajo Subdistrict | 283.12 km² | 21,955 | Rajo |

| SY020304 | Sharran Subdistrict | 305.18 km² | 13,632 | Sharran |

| SY020305 | Shaykh al-Hadid Subdistrict | 93.52 km² | 13,871 | Shaykh al-Hadid |

| SY020306 | Maabatli Subdistrict | 208.51 km² | 11,741 | Maabatli |

The administrative center of Afrin Subdistrict shown above is the city of Afrin.

The administrative center of Afrin Subdistrict shown above is the city of Afrin. The administrative center of Jindires Subdistrict shown above is the city of Jindires.

The administrative center of Jindires Subdistrict shown above is the city of Jindires. The administrative center of Shaykh al-Hadid Subdistrict shown above is the city of Shaykh al-Hadid.

The administrative center of Shaykh al-Hadid Subdistrict shown above is the city of Shaykh al-Hadid. The administrative center of Maabatli Subdistrict shown above is the city of Maabatli.

The administrative center of Maabatli Subdistrict shown above is the city of Maabatli. The administrative center of Sharran Subdistrict shown above is the city of Sharran.

The administrative center of Sharran Subdistrict shown above is the city of Sharran. The administrative center of Bulbul Subdistrict shown above is the city of Bulbul.

The administrative center of Bulbul Subdistrict shown above is the city of Bulbul. The administrative center of Rajo Subdistrict shown above is the city of Rajo.

The administrative center of Rajo Subdistrict shown above is the city of Rajo.

References

- "General Census of Population and Housing 2004" (PDF) (in Arabic). Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015. Also available in English: "2004 Census Data". UN OCHA. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "Turkey takes full control of Syria's Afrin region, reports say". Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Dussaud, René (1927). Topographie historique de la Syrie antique et médiévale. Geuthner. pp. 425.

- Chaliand, Gérard (1993). A People Without a Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan. Zed Books. p. 196. ISBN 9781856491945.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (2005). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-134-90766-3.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (2005). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-134-90766-3.

- Tejel, Jordi; Welle, Jane (2009). Syria's kurds history, politics and society (PDF) (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 100–101. ISBN 0-203-89211-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04.

- "SYRIA: The Silenced Kurds; Vol. 8, No. 4(E)". Human Rights Watch. 1996.

- Thomas Schmidinger (24 February 2016). "Afrin and the Race for the Azaz Corridor". Newsdeeply. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- "Nusra militants shell Kurdish areas in Syria's Afrin, Kurds respond". ARA News. 30 August 2015. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- "Turkish forces shell Afrin countryside, killing and injuring about 16 most of them from the self-defense forces and Asayish". SOHR. 9 July 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- "Turkey strikes Kurdish city of Afrin northern Syria, civilian casualties reported". ARA News. 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2016-10-23.

- "US and Russian military units patrol Kurdish-controlled areas in northern Syria". Al-Masdar. May 1, 2017.

- https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/kurds-locked-out-afrin-ghouta-refugees-take-their-place

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/07/too-many-strange-faces-kurds-fear-forced-demographic-shift-in-afrin

- Al Jazeera (16 March 2018). "Syrian civilians flee embattled Eastern Ghouta and Afrin". Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera Media Network. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "11 killed in bomb blast as Syria's Afrin falls to pro-Turkish forces". Middle East Eye. 19 March 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- Patrick Cockburn (18 April 2018). "Yazidis who suffered under Isis face forced conversion to Islam amid fresh persecution in Afrin". The Independent. Archived from the original on 13 June 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- Ammar Hamou; Barrett Limoges (1 May 2018). "Seizing lands from Afrin's displaced Kurds, Turkish-backed militias offer houses to East Ghouta families". SYRIA:direct. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Syria's war of ethnic cleansing: Kurds threatened with beheading by Turkey's allies if they don't convert to extremism". The Independent. 12 March 2018. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- https://missingafrinwomen.org/

- https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/06/syria-afrin-kidnappings-investigation-turkey-backed-rebels.html

- https://anfenglishmobile.com/features/dozens-of-girls-missing-in-afrin-25829

- https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/kurdish-woman-reported-murdered-in-turkish-occupied-afrin-630705

- https://www.voanews.com/extremism-watch/rights-groups-concerned-about-continued-abuses-afrin

- https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/kurdish-woman-reported-murdered-in-turkish-occupied-afrin-630705

- https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/erdogan-turkey-kurds-border-syria-war-trump-ethnic-cleansing-a9204581.html

- https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/looming-genocide-against-kurds-history-should-not-repeat-itself/

- "derStandard.at". DER STANDARD.

- "Rojava's Sustainability and the YPG's Regional Strategy". Washington Institute. 2 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Serious allegations against the Turkish government". Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker. 2 August 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- "1,150 emigrants enter Afrin canton". Hawar News Agency. 18 October 2016. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Will Afrin be the next Kobani?". Al-Monitor. 9 June 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

- "Afrin is building its economy on agriculture". Hawar News Agency. 8 August 2016. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "Agriculture Commission is Looking at the Process of Receiving Wheat from Farmers". Afrin Canton. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "Famous Aleppo soap victim of Syria's conflict". YourMiddleEast. 4 October 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Will Syria's Kurds succeed at self-sufficiency?". Al-Monitor. 3 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Will Syria's Kurds succeed at self-sufficiency?". Al-Monitor. 3 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- "Rojava: The Economic Branches in Detail". cooperativeeconomy.info. 14 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Khaled al-Khateb (26 July 2018). "Day trippers flock to Afrin's orchards as Aleppo restores security". al-Monitor. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

External links

![]() Media related to Afrin District at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Afrin District at Wikimedia Commons