Syrian civil war

The Syrian civil war (Arabic: الحرب الأهلية السورية, al-ḥarb al-ʾahlīyah as-sūrīyah) is an ongoing multi-sided civil war in Syria fought between the Ba'athist Syrian Arab Republic led by Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, along with domestic and foreign allies, and various domestic and foreign forces opposing both the Syrian government and each other in varying combinations.[109]

| Syrian civil war | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Spring, the Arab Winter, and the spillover of the Iraqi conflict | |||||||||||

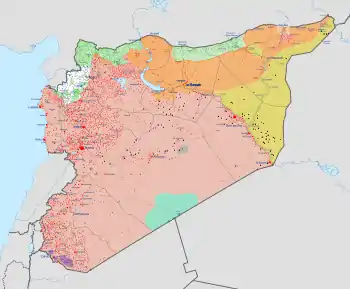

Military situation in February 2021: Syrian Arab Republic (SAA) Syrian Arab Republic & Rojava (SAA & SDF) Rojava (SDF) Syrian Interim Government (SNA) & Turkish occupation Syrian Salvation Government (HTS[a]) Revolutionary Commando Army & United States' occupation Opposition groups in reconciliation ISIL (full list of combatants, detailed map) | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Main belligerents | |||||||||||

|

|

Support:

Support:

|

Support:

|

Support:

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||||

Killed:

|

Killed:

Killed:

Killed:

|

Killed:

|

Killed:

| ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||||

| See order | See order | See order | See order | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||||

|

Syrian Armed Forces: 142,000 (2019)[68] General Security Directorate: 8,000[69] National Defense Force: 80,000[70] Liwa Fatemiyoun: 10,000 – 20,000(2018)[71] Liwa Abu al-Fadhal al-Abbas: 10,000+(2013)[72] Ba'ath Brigades: 7,000 Hezbollah: 6,000–8,000[73] Liwa Al-Quds: 4,000–8,000 Russia: 4,000 troops[74] & 1,000 contractors[75] Iran: 3,000–5,000[73][76] Other allied groups: 20,000+ |

Free Syrian Army: 20,000–32,000[77] (2013) Ahrar al-Sham: 18,000–20,000+[83][84] (March 2017) Tahrir al-Sham: 20,000-30,000 (per U.S., late 2018)[85] | ~3,000 (per Russia, mid 2019)[86][87] |

SDF: 60,000–75,000 (2017 est.)[88]

600[94] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||||

|

129,710–178,710 killed (68,049–103,049 soldiers & 52,391–66,391 militiamen) 4,100 soldiers/militiamen & 1,800 supporters captured[95] 1,703–2,000 killed[95][97] 133–156 soldiers[98] & 183–283 PMCs killed[99] Other non-Syrian fighters: 8,198 killed[95] (2,300–3,500+ IRGC-led)[100][101] |

230–285 killed (2016–20 incursions)[102] |

40,161 killed[95] |

13 killed[103] ( | ||||||||

|

116,911[95]–117,967[104] civilian deaths documented by opposition Total killed: 387,118–593,000 (per SOHR)[95] Estimated ≥7,600,000 internally displaced & ≥5,116,097 refugees (July 2015/2017)[105] a Formerly al-Nusra Front. b Since early 2013, the FSA has been decentralized. Its name is arbitrarily used by various rebels. c Turkey provided arms support to rebels (2011–unknown, Aug. 2016 – present) & fought alongside the TFSA in the Aleppo governorate vs. SDF, ISIL and Syrian gov. d Sep.–Nov. 2016: U.S. fought with the TFSA in Aleppo governorate solely vs. ISIL.[106][107] In 2017–18, the U.S. purposely attacked the Syrian gov. 10 times, & in Sep. 2016 it accidentally hit a Syrian base, killing ≥100 SAA soldiers. Syria maintains this as intentional.[108] e Predecessors of HTS (al-Nusra Front) & ISIL (ISI) were allied al-Qaeda branches until April 2013. Al-Nusra Front rejected an ISI-proposed merger into ISIL & al-Qaeda cut all affiliation with ISIL in February 2014. f Predecessors of Ahrar al-Sham (Syrian Liberation Front) & HTS (al-Nusra Front), were allied under the Army of Conquest (Mar. 2015 – Jan. 2017). g Number incl. all anti-government forces, except ISIL and SDF, which are listed in their separate columns. h Iraq's involvement was coordinated with the Syrian gov. & limited to airstrikes vs. ISIL.[2] | |||||||||||

The unrest in Syria, which began on 15 March 2011 as part of the wider 2011 Arab Spring protests, grew out of discontent with the Syrian government and escalated to an armed conflict after protests calling for Assad's removal were violently suppressed.[110][111][112] The war is being fought by several factions: the Syrian Armed Forces and its domestic and international allies, a loose alliance of mostly Sunni opposition rebel groups (such as the Free Syrian Army), Salafi jihadist groups (including al-Nusra Front and Tahrir al-Sham), the mixed Kurdish-Arab Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). A number of foreign countries, such as Iran, Israel, Russia, Turkey, and the United States, have either directly involved themselves in the conflict or provided support to one or another faction.

Iran, Russia, and Hezbollah support the Syrian Arab Republic and the Syrian Armed Forces militarily, with Russia conducting airstrikes and other military operations since September 2015. The U.S.-led international coalition, established in 2014 with the declared purpose of countering ISIL, has conducted airstrikes primarily against ISIL as well as some against government and pro-government targets. They have also deployed special forces and artillery units to engage ISIL on the ground. Since 2015, the U.S. has supported the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and its armed wing, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), materially, financially, and logistically. At different times, the Turkish state has fought the SDF, ISIL, and the Syrian government since 2016, but has also actively supported the Syrian opposition and occupied large swaths of northwestern Syria while engaging in significant ground combat. Between 2011 and 2017, fighting from the Syrian civil war spilled over into Lebanon as opponents and supporters of the Syrian government traveled to Lebanon to fight and attack each other on Lebanese soil, with ISIL and Al-Nusra also engaging the Lebanese Army. Furthermore, while officially neutral, Israel has exchanged fire with Hezbollah and Iranian forces, whose presence in southwestern Syria it views as a threat.[113] It has also carried out repeated strikes in the rest of Syria since the start of the war, mainly targeting alleged Iranian and Hezbollah militants.[114]

International organizations have criticized virtually all sides involved, including the Ba'athist Syrian government, ISIL, opposition rebel groups, Russia,[115] Turkey,[116] and the U.S.-led coalition[117] of severe human rights violations and massacres.[118] The conflict has caused a major refugee crisis. Over the course of the war, a number of peace initiatives have been launched, including the March 2017 Geneva peace talks on Syria led by the United Nations, but fighting has continued.[119]

| Part of a series on |

| Baathism |

|---|

|

|

Background

Assad government

The secular Ba'ath Syrian Regional Branch government came to power through a coup d'état in 1963. For several years Syria went through additional coups and changes in leadership,[120] until in March 1971, Hafez al-Assad, an Alawite, declared himself President. The secular Syrian Regional Branch remained the dominant political authority in what had been a one-party state until the first multi-party election to the People's Council of Syria was held in 2012.[121] On 31 January 1973, Hafez al-Assad implemented a new constitution, which led to a national crisis. Unlike previous constitutions, this one did not require that the president of Syria be a Muslim, leading to fierce demonstrations in Hama, Homs and Aleppo organized by the Muslim Brotherhood and the ulama. The government survived a series of armed revolts by Islamists, mainly members of the Muslim Brotherhood, from 1976 until 1982.

Upon Hafez al-Assad's death in 2000, his son Bashar al-Assad was elected as President of Syria. Bashar and his wife Asma, a Sunni Muslim born and educated in Britain,[122] initially inspired hopes for democratic reforms; however, according to his critics, Bashar failed to deliver on promised reforms.[123] President Al-Assad maintained in 2017 that no 'moderate opposition' to his rule exists, and that all opposition forces are jihadists intent on destroying his secular leadership; his view was that terrorist groups operating in Syria are 'linked to the agendas of foreign countries'.[124]

Demographics

The total population in July 2018 was estimated at 19,454,263 people; ethnic groups – approximately Arab 50%, Alawite 15%, Kurd 10%, Levantine 10%, other 15% (includes Druze, Ismaili, Imami, Assyrian, Turkmen, Armenian); religions – Muslim 87% (official; includes Sunni 74% and Alawi, Ismaili, and Shia 13%), Christian 10% (mainly of Eastern Christian churches[125] – may be smaller as a result of Christians fleeing the country), Druze 3% and Jewish (few remaining in Damascus and Aleppo).[126]

Socioeconomic background

Socioeconomic inequality increased significantly after free market policies were initiated by Hafez al-Assad in his later years, and it accelerated after Bashar al-Assad came to power. With an emphasis on the service sector, these policies benefited a minority of the nation's population, mostly people who had connections with the government, and members of the Sunni merchant class of Damascus and Aleppo.[127] In 2010, Syria's nominal GDP per capita was only $2,834, comparable to Sub-Saharan African countries such as Nigeria and far lower than its neighbors such as Lebanon, with an annual growth rate of 3.39%, below most other developing countries.[128]

The country also faced particularly high youth unemployment rates.[129] At the start of the war, discontent against the government was strongest in Syria's poor areas, predominantly among conservative Sunnis.[127] These included cities with high poverty rates, such as Daraa and Homs, and the poorer districts of large cities.

Drought

This coincided with the most intense drought ever recorded in Syria, which lasted from 2006 to 2011 and resulted in widespread crop failure, an increase in food prices and a mass migration of farming families to urban centers.[130] This migration strained infrastructure already burdened by the influx of some 1.5 million refugees from the Iraq War.[131] The drought has been linked to anthropogenic global warming.[132][133][134] Adequate water supply continues to be an issue in the ongoing civil war and it is frequently the target of military action.[135]

Human rights

The human rights situation in Syria has long been the subject of harsh critique from global organizations.[136] The rights of free expression, association and assembly were strictly controlled in Syria even before the uprising.[137] The country was under emergency rule from 1963 until 2011 and public gatherings of more than five people were banned.[138] Security forces had sweeping powers of arrest and detention.[139] Despite hopes for democratic change with the 2000 Damascus Spring, Bashar al-Assad was widely reported as having failed to implement any improvements. A Human Rights Watch report issued just before the beginning of the 2011 uprising stated that he had failed to substantially improve the state of human rights since taking power.[140]

Timeline

Protests, civil uprising, and defections (March–July 2011)

Initial armed insurgency (July 2011 – April 2012)

.svg.png.webp)

Kofi Annan ceasefire attempt (April–May 2012)

Third phase of the war starts: escalation (2012–2013)

Rise of the Islamist groups (January–September 2014)

US intervention (September 2014 – September 2015)

Russian intervention (September 2015 – March 2016), including first partial ceasefire

Aleppo recaptured; Russian/Iranian/Turkish-backed ceasefire (December 2016 – April 2017)

Syrian-American conflict; de-escalation Zones (April 2017 – June 2017)

ISIL siege of Deir ez-Zor broken; CIA program halted; Russian forces permanent (July 2017–Dec. 2017)

Army advance in Hama province and Ghouta; Turkish intervention in Afrin (January–March 2018)

Douma chemical attack; U.S.-led missile strikes; Southern Syria offensive (April 2018 – August 2018)

Idlib demilitarization; Trump announces US withdrawal; Iraq strikes ISIL targets (September–December 2018)

.svg.png.webp)

ISIL attacks continue; US states conditions of withdrawal; Fifth inter-rebel conflict (January–May 2019)

Demilitarization agreement falls apart; 2019 Northwestern Syria offensive; Northern Syria Buffer Zone established (May–October 2019)

U.S. forces withdraw from buffer zone; Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria (October 2019)

Northwestern offensive; Baylun airstrikes; Operation Spring Shield; Daraa clashes; Afrin bombing (late 2019; 2020)

Belligerents

Syrian factions

There are numerous factions, both foreign and domestic, involved in the Syrian civil war. These can be divided in four main groups. First, the Syrian Armed Forces and its allies. Second, the opposition composed from the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army,[141] the Free Syrian Army and the jihadi Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.[142] Third, the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces.[143] Fourth, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.[144] The Syrian government, the opposition and the SDF have all received support, militarily and diplomatically, from foreign countries, leading the conflict to often be described as a proxy war.[145]

Foreign involvement

The major parties supporting the Syrian Government are Iran,[146] Russia[147] and the Lebanese Hezbollah. Syrian rebel groups received political, logistic and military support from the United States,[148][149] Turkey,[150] Saudi Arabia,[151] Qatar,[152] Britain, France,[153] Israel,[154] and the Netherlands.[155] Under the aegis of operation Timber Sycamore and other clandestine activities, CIA operatives and U.S. special operations troops have trained and armed nearly 10,000 rebel fighters at a cost of $1 billion a year since 2012.[156][157] Iraq had also been involved in supporting the Syrian government, but mostly against ISIL.[158]

On August 6, 2020, Saad Aljabri, in a complaint filed in a federal court in the Washington accused Mohammed Bin Salman of secretly inviting Russia to intervene in Syria at a time when Bashar al-Assad was close to falling in 2015.[159]

Spillover

In June 2014, members of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) crossed the border from Syria into northern Iraq, and took control of large swaths of Iraqi territory as the Iraqi Army abandoned its positions. Fighting between rebels and government forces also spilled over into Lebanon on several occasions. There were repeated incidents of sectarian violence in the North Governorate of Lebanon between supporters and opponents of the Syrian government, as well as armed clashes between Sunnis and Alawites in Tripoli.[160]

Starting on 5 June 2014, ISIL seized swathes of territory in Iraq. As of 2014, the Syrian Arab Air Force used airstrikes targeted against ISIL in Raqqa and al-Hasakah in coordination with the Iraqi government.[161]

Advanced weaponry and tactics

Destruction of chemical weapons

Sarin, mustard agent and chlorine gas have been used during the conflict. Numerous casualties led to an international reaction, especially the 2013 Ghouta attacks. A UN fact-finding mission was requested to investigate reported chemical weapons attacks. In four cases UN inspectors confirmed the use of sarin gas.[162] In August 2016, a confidential report by the United Nations and the OPCW explicitly blamed the Syrian military of Bashar al-Assad for dropping chemical weapons (chlorine bombs) on the towns of Talmenes in April 2014 and Sarmin in March 2015 and ISIS for using sulfur mustard on the town of Marea in August 2015.[163]

The United States and the European Union have said the Syrian government has conducted several chemical attacks. Following the 2013 Ghouta attacks and international pressure, the destruction of Syria's chemical weapons began. In 2015 the UN mission disclosed previously undeclared traces of sarin compounds in a "military research site".[164] After the April 2017 Khan Shaykhun chemical attack, the United States launched its first attack against Syrian government forces.

In June 2019, United States Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Michael Mulroy stated that the United States "will respond quickly and appropriately,” if the government uses chemical weapons again. He added that Bashar al-Assad has done more than any other to destabilize the region by "murdering his own people" and that both Russia and the Syrian government have shown no concern for the suffering of the Syrian people creating one of the "worst humanitarian tragedies in history".[165]

On April 15, the UN Security Council briefing was held on the findings of a global chemical weapons watchdog, Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), which claimed that the Syrian air force used sarin and chlorine for multiple attacks, in 2017. The close allies of Syria, Russia and European countries debated on the issue, where the claims were dismissed by Moscow and the Europeans called for accountability for government's actions.[166] The UN Deputy ambassador from Britain, Jonathan Allen stated that report by OPCW's Investigation Identification Team (IIT) revealed that the Assad government is responsible for using chemical weapons against its own people, on at least four occasions. The information was also exposed in two UN-mandated investigations.[167]

Cluster bombs

Syria is not a party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions and does not recognize the ban on the use of cluster bombs. The Syrian Army is reported to have begun using cluster bombs in September 2012. Steve Goose, director of the Arms Division at Human Rights Watch said "Syria is expanding its relentless use of cluster munitions, a banned weapon, and civilians are paying the price with their lives and limbs", "The initial toll is only the beginning because cluster munitions often leave unexploded bomblets that kill and maim long afterward".[168]

Thermobaric weapons

Russian thermobaric weapons, also known as "fuel-air bombs", were used by the government side during the war. On 2 December 2015, The National Interest reported that Russia was deploying the TOS-1 Buratino multiple rocket launch system to Syria, which is "designed to launch massive thermobaric charges against infantry in confined spaces such as urban areas".[169] One Buratino thermobaric rocket launcher "can obliterate a roughly 200 by 400 metres (660 by 1,310 feet) area with a single salvo".[170] Since 2012, rebels have said that the Syrian Air Force (government forces) is using thermobaric weapons against residential areas occupied by the rebel fighters, such as during the Battle of Aleppo and also in Kafr Batna.[171] A panel of United Nations human rights investigators reported that the Syrian government used thermobaric bombs against the strategic town of Qusayr in March 2013.[172] In August 2013, the BBC reported on the use of napalm-like incendiary bombs on a school in northern Syria.[173]

Anti-tank missiles

Several types of anti-tank missiles are in use in Syria. Russia has sent 9M133 Kornet, third-generation anti-tank guided missiles to the Syrian Government whose forces have used them extensively against armour and other ground targets to fight Jihadists and rebels.[174] U.S.-made BGM-71 TOW missiles are one of the primary weapons of rebel groups and have been primarily provided by the United States and Saudi Arabia.[175] The U.S. has also supplied many Eastern European sourced 9K111 Fagot launchers and warheads to Syrian rebel groups under its Timber Sycamore program.[176]

Ballistic missiles

In June 2017, Iran attacked ISIL targets in the Deir ez-Zor area in eastern Syria with Zolfaghar ballistic missiles fired from western Iran,[177] in the first use of mid-range missiles by Iran in 30 years.[178] According to Jane's Defence Weekly, the missiles travelled 650–700 kilometres.[177]

Media coverage

The Syrian civil war is one of the most heavily documented wars in history, despite the extreme dangers that journalists face while in Syria.[179]

ISIL and al-Qaeda executions

On 19 August 2014, American journalist James Foley was executed by ISIL, who said it was in retaliation for the United States operations in Iraq. Foley was kidnapped in Syria in November 2012 by Shabiha militia.[180] ISIL also threatened to execute Steven Sotloff, who was kidnapped at the Syrian-Turkish border in August 2013.[181] There were reports ISIS captured a Japanese national, two Italian nationals, and a Danish national as well.[182] Sotloff was later executed in September 2014. At least 70 journalists have been killed covering the Syrian war, and more than 80 kidnapped, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.[183] On 22 August 2014, the al-Nusra Front released a video of captured Lebanese soldiers and demanded Hezbollah withdraw from Syria under threat of their execution.[184]

International reactions

.jpg.webp)

During the early period of the civil war, The Arab League, European Union, the United Nations,[185] and many Western governments quickly condemned the Syrian government's violent response to the protests, and expressed support for the protesters' right to exercise free speech.[186] Initially, many Middle Eastern governments expressed support for Assad, but as the death toll mounted, they switched to a more balanced approach by criticizing violence from both government and protesters. Both the Arab League and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation suspended Syria's membership. Russia and China vetoed Western-drafted United Nations Security Council resolutions in 2011 and 2012, which would have threatened the Syrian government with targeted sanctions if it continued military actions against protestors.[187]

Sectarian threats

The successive governments of Hafez and Bashar al-Assad have been closely associated with the country's minority Alawite religious group,[188] an offshoot of Shia, whereas the majority of the population, and most of the opposition, is Sunni. Alawites started to be threatened and attacked by dominantly Sunni rebel fighting groups like al-Nusra Front and the FSA since December 2012 (see Sectarianism and minorities in the Syrian Civil War#Alawites).

A third of 250,000 Alawite men of military age have been killed fighting in the Syrian civil war.[189] In May 2013, SOHR stated that out of 94,000 killed during the war, at least 41,000 were Alawites.[190]

Many Syrian Christians reported that they had fled after they were targeted by the anti-government rebels.[191] (See: Sectarianism and minorities in the Syrian Civil War#Christians.)

The Druze community in Syria has been divided by the civil war, and has experienced persecution by Islamist rebels, ISIL, the government and the government's Hezbollah allies. (See: Sectarianism and minorities in the Syrian Civil War#Druze.)

As militias and non-Syrian Shia—motivated by pro-Shia sentiment rather than loyalty to the Assad government—have taken over fighting the opposition from the weakened Syrian Army, fighting has taken on a more sectarian nature. One opposition leader has said that the Shia militias often "try to occupy and control the religious symbols in the Sunni community to achieve not just a territorial victory but a sectarian one as well"[192]—reportedly occupying mosques and replacing Sunni icons with pictures of Shia leaders.[192] According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, human rights abuses have been committed by the militias including "a series of sectarian massacres between March 2011 and January 2014 that left 962 civilians dead".[192]

Crime wave

As the conflict has expanded across Syria, many cities have been engulfed in a wave of crime as fighting caused the disintegration of much of the civilian state, and many police stations stopped functioning. Rates of theft increased, with criminals looting houses and stores. Rates of kidnappings increased as well. Rebel fighters were seen stealing cars and, in one instance, destroying a restaurant in Aleppo where Syrian soldiers had been seen eating.[193]

Local National Defense Forces commanders often engaged "in war profiteering through protection rackets, looting, and organized crime". NDF members were also implicated in "waves of murders, robberies, thefts, kidnappings, and extortions throughout government-held parts of Syria since the formation of the organization in 2013", as reported by the Institute for the Study of War.[194]

Criminal networks have been used by both the government and the opposition during the conflict. Facing international sanctions, the Syrian government relied on criminal organizations to smuggle goods and money in and out of the country. The economic downturn caused by the conflict and sanctions also led to lower wages for Shabiha members. In response, some Shabiha members began stealing civilian properties and engaging in kidnappings.[195] Rebel forces sometimes rely on criminal networks to obtain weapons and supplies. Black market weapon prices in Syria's neighboring countries have significantly increased since the start of the conflict. To generate funds to purchase arms, some rebel groups have turned towards extortion, theft, and kidnapping.[195]

Cultural heritage

In January 2018 Turkish air strikes have seriously damaged an ancient Neo-Hittite temple in Syria's Kurdish-held Afrin region. It was built by the Arameans in the first millennium BC.[196]

As of March 2015, the war has affected 290 heritage sites, severely damaged 104, and completely destroyed 24. Five of the six UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Syria have been damaged.[197] Destruction of antiquities has been caused by shelling, army entrenchment, and looting at various tells, museums, and monuments.[198] A group called Syrian Archaeological Heritage Under Threat is monitoring and recording the destruction in an attempt to create a list of heritage sites damaged during the war and to gain global support for the protection and preservation of Syrian archaeology and architecture.[199]

UNESCO listed all six Syria's World Heritage sites as endangered but direct assessment of damage is not possible. It is known that the Old City of Aleppo was heavily damaged during battles being fought within the district, while Palmyra and Krak des Chevaliers suffered minor damage. Illegal digging is said to be a grave danger, and hundreds of Syrian antiquities, including some from Palmyra, appeared in Lebanon. Three archeological museums are known to have been looted; in Raqqa some artifacts seem to have been destroyed by foreign Islamists due to religious objections.[200]

In 2014 and 2015, following the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, several sites in Syria were destroyed by the group as part of a deliberate destruction of cultural heritage sites. In Palmyra, the group destroyed many ancient statues, the Temples of Baalshamin and Bel, many tombs including the Tower of Elahbel, and part of the Monumental Arch.[201] The 13th-century Palmyra Castle was extensively damaged by retreating militants during the Palmyra offensive in March 2016.[202] ISIL also destroyed ancient statues in Raqqa,[203] and a number of churches, including the Armenian Genocide Memorial Church in Deir ez-Zor.[204]

According to a September 2019 Syrian Network for Human Rights reports more than 120 Christian churches have been destroyed or damaged in Syria since 2011.[205]

The war has inspired its own particular artwork, done by Syrians. A late summer 2013 exhibition in London at the P21 Gallery showed some of this work, which had to be smuggled out of Syria.[206]

Human toll

| Population 21 ±.5: Displaced 6 ±.5, Refugee 5.5 ±.5, Casualty 0.5 ±.1 (millions) | |

| Syrian refugees | |

| By country | Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt |

| Settlements | Camps: (Jordan) |

| Displaced Syrians | |

| Casualties of the war | |

| Crimes | Human rights violations, massacres, rape |

| Return of refugees · Refugees as weapons · Prosecution of war criminals | |

Refugees

As of 2015, 3.8 million have been made refugees.[197] As of 2013, 1 in 3 of Syrian refugees (about 667,000 people) sought safety in Lebanon (normally 4.8 million population).[207] Others have fled to Jordan, Turkey, and Iraq. Turkey has accepted 1,700,000 (2015) Syrian refugees, half of whom are spread around cities and a dozen camps placed under the direct authority of the Turkish Government. Satellite images confirmed that the first Syrian camps appeared in Turkey in July 2011, shortly after the towns of Deraa, Homs, and Hama were besieged.[208] In September 2014, the UN stated that the number of Syrian refugees had exceeded 3 million.[209] According to the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, Sunnis are leaving for Lebanon and undermining Hezbollah's status. The Syrian refugee crisis has caused the "Jordan is Palestine" threat to be diminished due to the onslaught of new refugees in Jordan. Greek Catholic Patriarch Gregorios III Laham says more than 450,000 Syrian Christians have been displaced by the conflict.[210] As of September 2016, the European Union has reported that there are 13.5 million refugees in need of assistance in the country.[211] Australia is being appealed to rescue more than 60 women and children stuck in Syria's Al-Hawl camp ahead of a potential Turkish invasion.[212]

Internally displaced

The violence in Syria caused millions to flee their homes. As of March 2015, Al-Jazeera estimate 10.9 million Syrians, or almost half the population, have been displaced.[197] Violence erupted due to the ongoing crisis in northwest Syria has forced 6,500 children to flee every day over the last week of January 2020. The recorded count of displaced children in the area has reached more than 300,000 since December 2019.[213]

Casualties

.png.webp)

On 2 January 2013, the United Nations stated that 60,000 had been killed since the civil war began, with UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay saying "The number of casualties is much higher than we expected, and is truly shocking".[215] Four months later, the UN's updated figure for the death toll had reached 80,000.[216] On 13 June 2013, the UN released an updated figure of people killed since fighting began, the figure being exactly 92,901, for up to the end of April 2013. Navi Pillay, UN high commissioner for human rights, stated that: "This is most likely a minimum casualty figure". The real toll was guessed to be over 100,000.[217][218] Some areas of the country have been affected disproportionately by the war; by some estimates, as many as a third of all deaths have occurred in the city of Homs.[219]

One problem has been determining the number of "armed combatants" who have died, due to some sources counting rebel fighters who were not government defectors as civilians.[220] At least half of those confirmed killed have been estimated to be combatants from both sides, including 52,290 government fighters and 29,080 rebels, with an additional 50,000 unconfirmed combatant deaths.[95] In addition, UNICEF reported that over 500 children had been killed by early February 2012,[221] and another 400 children have been reportedly arrested and tortured in Syrian prisons;[222] both of these reports have been contested by the Syrian government. Additionally, over 600 detainees and political prisoners are known to have died under torture.[223] In mid-October 2012, the opposition activist group SOHR reported the number of children killed in the conflict had risen to 2,300,[224] and in March 2013, opposition sources stated that over 5,000 children had been killed.[225] In January 2014, a report was released detailing the systematic killing of more than 11,000 detainees of the Syrian government.[226]

On 20 August 2014, a new U.N. study concluded that at least 191,369 people have died in the Syrian conflict.[227] The UN thereafter stopped collecting statistics, but a study by the Syrian Centre for Policy Research released in February 2016 estimated the death toll to be 470,000, with 1.9m wounded (reaching a total of 11.5% of the entire population either wounded or killed).[228] A report by the pro-opposition SNHR in 2018 mentioned 82000 victims that had been forcibly disappeared by the Syrian government, added to 14.000 confirmed deaths due to torture.[229]

On April 15, 2017 a convoy of buses carrying evacuees from the besieged Shia towns of al-Fu'ah and Kafriya, which were surrounded by the Army of Conquest,[230] was attacked by a suicide bomber west of Aleppo,[231] killing more than 126 people, including at least 80 children.[232]

On January 1, 2020, at least eight civilians, including four children, were killed in a rocket attack on a school in Idlib by Syrian government forces, the Syrian Human Rights Observatory (SOHR) said.[233]

In January 2020, UNICEF warned that children were bearing the brunt of escalating violence in northwestern Syria. More than 500 children were wounded or killed during the first three quarters of 2019, and over 65 children fell victim to the war in December alone.[234]

Over 380,000 people were killed since the war in Syria started nine years ago, war monitor Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said on January 4, 2020. The death toll comprises civilians, government soldiers, militia members and foreign troops.[235]

In an airstrike by Russian forces loyal to the Syrian government, at least five civilians were killed, out of which four belonged to the same family. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights claimed that the death toll included three children following the attack in the Idlib region on January 18, 2020.[236]

On January 30, 2020, Russian air strikes on a hospital and a bakery killed over 10 civilians in Syria's Idlib region. Moscow immediately rejected the allegation.[237]

On 23 June 2020, Israeli raids killed seven fighters, including two Syrian in a central province. State media cited a military official as saying the attack targeted posts in rural areas of Hama province.[238]

Human rights violations

According to various human rights organizations and United Nations, human rights violations have been committed by both the government and the rebels, with the "vast majority of the abuses having been committed by the Syrian government".[239]

According to three international lawyers,[240] Syrian government officials could face war crimes charges in the light of a huge cache of evidence smuggled out of the country showing the "systematic killing" of about 11,000 detainees. Most of the victims were young men and many corpses were emaciated, bloodstained and bore signs of torture. Some had no eyes; others showed signs of strangulation or electrocution.[241] Experts said this evidence was more detailed and on a far larger scale than anything else that had emerged from the then 34-month crisis.[242]

The UN also reported in 2014 that "siege warfare is employed in a context of egregious human rights and international humanitarian law violations. The warring parties do not fear being held accountable for their acts". Armed forces of both sides of the conflict blocked access of humanitarian convoys, confiscated food, cut off water supplies and targeted farmers working their fields. The report pointed to four places besieged by the government forces: Muadamiyah, Daraya, Yarmouk camp and Old City of Homs, as well as two areas under siege of rebel groups: Aleppo and Hama.[243][244] In Yarmouk Camp 20,000 residents faced death by starvation due to blockade by the Syrian government forces and fighting between the army and Jabhat al-Nusra, which prevents food distribution by UNRWA.[243][245] In July 2015, the UN removed Yarmouk from its list of besieged areas in Syria, despite not having been able deliver aid there for four months, and declined to say why it had done so.[246] After intense fighting in April/May 2018, Syrian government forces finally took the camp, its population now reduced to 100–200.[247]

ISIS forces have been criticized by the UN of using public executions and killing of captives, amputations, and lashings in a campaign to instill fear. "Forces of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham have committed torture, murder, acts tantamount to enforced disappearance and forced displacement as part of attacks on the civilian population in Aleppo and Raqqa governorates, amounting to crimes against humanity", said the report from 27 August 2014.[248] ISIS also persecuted gay and bisexual men.[249]

Enforced disappearances and arbitrary detentions have also been a feature since the Syrian uprising began.[250] An Amnesty International report, published in November 2015, stated the Syrian government has forcibly disappeared more than 65,000 people since the beginning of the Syrian civil war.[251] According to a report in May 2016 by the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, at least 60,000 people have been killed since March 2011 through torture or from poor humanitarian conditions in Syrian government prisons.[252]

In February 2017, Amnesty International published a report which stated the Syrian government murdered an estimated 13,000 persons, mostly civilians, at the Saydnaya military prison. They stated the killings began in 2011 and were still ongoing. Amnesty International described this as a "policy of deliberate extermination" and also stated that "These practices, which amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity, are authorised at the highest levels of the Syrian government".[253] Three months later, the United States State Department stated a crematorium had been identified near the prison. According to the U.S., it was being used to burn thousands of bodies of those killed by the government's forces and to cover up evidence of atrocities and war crimes.[254] Amnesty International expressed surprise at the reports about the crematorium, as the photographs used by the US are from 2013 and they did not see them as conclusive, and fugitive government officials have stated that the government buries those its executes in cemeteries on military grounds in Damascus.[255] The Syrian government said the reports were not true.

By July 2012, the human rights group Women Under Siege had documented over 100 cases of rape and sexual assault during the conflict, with many of these crimes reported to have been perpetrated by the Shabiha and other pro-government militias. Victims included men, women, and children, with about 80% of the known victims being women and girls.[256] A report by the United Nations Human Rights Council states that "women and girls as young as nine are being sold as slaves to ISIS soldiers who regularly beat them and rape them, re-sell them, and, if they try to escape, kill them".[257]

On September 11, 2019, the UN investigators said that air strikes conducted by the US-led coalition in Syria have killed or wounded several civilians, denoting that necessary precautions were not taken leading to potential war crimes.[258]

In late 2019, as the violence intensified in north-west Syria, thousands of women and children were reportedly kept under "inhumane conditions" in a remote camp, said UN-appointed investigators.[259] In October 2019, Amnesty International stated that it had gathered evidence of war crimes and other violations committed by Turkish and Turkey-backed Syrian forces who are said to "have displayed a shameful disregard for civilian life, carrying out serious violations and war crimes, including summary killings and unlawful attacks that have killed and injured civilians".[116]

According to a new report by U.N.-backed investigators into the Syrian civil war, young girls aged nine and above, have been raped and inveigled into sexual slavery. While, boys have been put through torture and forcefully trained to execute killings in public. Children have been attacked by sharp shooters and lured by bargaining chips to pull out ransoms.[260]

On April 6, 2020, the United Nations published its investigation into the attacks on humanitarian sites in Syria. The council in its reports said, it had examined 6 sites of attacks and concluded that the airstrikes had been carried out by the "Government of Syria and/or its allies.” However, the report was criticized for being partial towards Russia and not naming it, despite proper evidence. "The refusal to explicitly name Russia as a responsible party working alongside the Syrian government … is deeply disappointing,” the HRW quoted.[261]

On 27 April 2020, the Syrian Network for Human Rights reported continuation of multiple crimes in the month of March and April in Syria. The rights organization billed that Syrian regime decimated 44 civilians, including six children, during the unprecedented times of COVID-19. It also said, Syrian forces held captive 156 people, while committing a minimum of four attacks on vital civilian facilities. The report further recommended that the UN impose sanctions on the Bashar al-Assad regime, if it continues to commit human rights violation.[262]

On May 8, 2020, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, raised serious concern that rebel groups, including ISIL terrorist fighters, may be using the COVID-19 pandemic as “an opportunity to re-group and inflict violence in the country”.[263]

On 21 July 2020, the Syrian government forces carried out an attack and killed two civilians with four Grad rockets in western al-Bab sub-district.[264]

Epidemics

The World Health Organization has reported that 35% of the country's hospitals are out of service. Fighting makes it impossible to undertake the normal vaccination programs. The displaced refugees may also pose a disease risk to countries to which they have fled.[265] 400,000 civilians were isolated by the Siege of Eastern Ghouta from April 2013 to April 2018, resulting in acutely malnourished children according to the United Nations Special Advisor, Jan Egeland, who urged the parties for medical evacuations. 55,000 civilians are also isolated in the Rukban refugee camp between Syria and Jordan, where humanitarian relief access is difficult due to the harsh desert conditions. Humanitarian aid reaches the camp only sporadically, sometimes taking three months between shipments.[266][267]

Formerly rare infectious diseases have spread in rebel-held areas brought on by poor sanitation and deteriorating living conditions. The diseases have primarily affected children. These include measles, typhoid, hepatitis, dysentery, tuberculosis, diphtheria, whooping cough and the disfiguring skin disease leishmaniasis. Of particular concern is the contagious and crippling Poliomyelitis. As of late 2013 doctors and international public health agencies have reported more than 90 cases. Critics of the government complain that, even before the uprising, it contributed to the spread of disease by purposefully restricting access to vaccination, sanitation and access to hygienic water in "areas considered politically unsympathetic".[268]

In June 2020, the United Nations reported that after more than nine years of war, Syria was falling into an even deeper crisis and economic deterioration as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. As of June 26, a total of 248 people were infected by COVID-19, out of which nine people lost their lives. Restrictions on the importation of medical supplies, limited access to essential equipment, reduced outside support and ongoing attacks on medical facilities left Syria's health infrastructure in peril, and unable to meet the needs of its population. Syrian communities were additionally facing an unprecedented levels of hunger crisis.[269]

Humanitarian aid

The conflict holds the record for the largest sum ever requested by UN agencies for a single humanitarian emergency, $6.5 billion worth of requests of December 2013.[270] The international humanitarian response to the conflict in Syria is coordinated by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) in accordance with General Assembly Resolution 46/182.[271] The primary framework for this coordination is the Syria Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP) which appealed for US$1.41 billion to meet the humanitarian needs of Syrians affected by the conflict.[272] Official United Nations data on the humanitarian situation and response is available at an official website managed by UNOCHA Syria (Amman).[273] UNICEF is also working alongside these organizations to provide vaccinations and care packages to those in need. Financial information on the response to the SHARP and assistance to refugees and for cross-border operations can be found on UNOCHA's Financial Tracking Service. As of 19 September 2015, the top ten donors to Syria were United States, European Commission, United Kingdom, Kuwait, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Japan, UAE, and Norway.[274]

The difficulty of delivering humanitarian aid to people is indicated by the statistics for January 2015: of the estimated 212,000 people during that month who were besieged by government or opposition forces, 304 were reached with food.[275] USAID and other government agencies in US delivered nearly $385 million of aid items to Syria in 2012 and 2013. The United States has provided food aid, medical supplies, emergency and basic health care, shelter materials, clean water, hygiene education and supplies, and other relief supplies.[276] Islamic Relief has stocked 30 hospitals and sent hundreds of thousands of medical and food parcels.[277]

Other countries in the region have also contributed various levels of aid. Iran has been exporting between 500 and 800 tonnes of flour daily to Syria.[278] Israel supplied aid through Operation Good Neighbor, providing medical treatment to 750 Syrians in a field hospital located in Golan Heights where rebels say that 250 of their fighters were treated.[279] Israel established two medical centers inside Syria. Israel also delivered heating fuel, diesel fuel, seven electric generators, water pipes, educational materials, flour for bakeries, baby food, diapers, shoes and clothing. Syrian refugees in Lebanon make up one quarter of Lebanon's population, mostly consisting of women and children.[280] In addition, Russia has said it created six humanitarian aid centers within Syria to support 3000 refugees in 2016.[281]

On April 9, 2020, the UN dispatched 51 truckloads of humanitarian aid to Idlib. The organization said that the aid would be distributed among civilians stranded in the north-western part of the country.[282]

On April 30, 2020, Human Rights Watch condemned the Syrian authorities for their longstanding restriction on the entry of aid supplies.[283] It also demanded the World Health Organization to keep pushing the UN to allow medical aid and other essentials to reach Syria via the Iraq border crossing, to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the war-torn nation. The aid supplies, if allowed, will allow the Syrian population to protect themselves from contracting the COVID-19 virus.[284]

Return of refugees

Another aspect of the post war years will be how to repatriate the millions of refugees. The Syrian government has put forward a law commonly known as "law 10", which could strip refugees of property, such as damaged real estate. There are also fears among some refugees that if they return to claim this property they will face negative consequences, such as forced conscription or prison. The Syrian government has been criticized for using this law to reward those who have supported the government. However, the government said this statement was false and has expressed that it wants the return of refugees from Lebanon.[285][286] In December 2018, it was also reported that the Syrian government has started to seize property under an anti-terrorism law, which is affecting government opponents negatively, with many losing their property. Some people's pensions have also been cancelled.[287]

Erdogan said that Turkey expects to resettle about 1 million refugees in the "buffer zone" that it controls.[288][289][290][291] Erdogan claimed that Turkey had spent billions on approximately five million refugees now being housed in Turkey; and called for more funding from wealthier nations and from the EU.[292][293][294][295][296][297] This plan raised concerns amongst Kurds about displacement of existing communities and groups in that area.

Destruction and reconstruction

United Nations authorities have estimated that the war in Syria has caused destruction reaching to about $400 billion.[298]

While the war still ongoing, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad said that Syria would be able to rebuild the war-torn country on its own. As of July 2018, the reconstruction is estimated to cost a minimum of US$400 billion. Assad said he would be able to loan this money from friendly countries, Syrian diaspora and the state treasury.[299] Iran has expressed interest in helping rebuild Syria.[300] One year later this seems to be materializing, Iran and the Syrian government signed a deal where Iran would help rebuild the Syrian energy grid, which has taken damage to 50% of the grid.[301] International donors have been suggested as one financier of the reconstruction.[302] As of November 2018, reports emerged that rebuilding efforts had already started. It was reported that the biggest issue facing the rebuilding process is the lack of building material and a need to make sure the resources that do exist are managed efficiently. The rebuilding effort have so far remained at a limited capacity and has often been focused on certain areas of a city, thus ignoring other areas inhabited by disadvantaged people.[303]

According to a Syrian war monitor, over 120 Churches have been damaged or demolished by all sides in Syrian war since 2011.[304]

Various efforts are proceeding to rebuild infrastructure in Syria. Russia says it will spend $500 million to modernize Syria's port of Tartus. Russia also said it will build a railway to link Syria with the Persian Gulf.[305][306] Russia will also contribute to recovery efforts by the UN.[307] Syria awarded oil exploration contracts to two Russian firms.[308]

Syria announced it is in serious dialogue with China to join China's "Belt and Road Initiative" designed to foster investment in infrastructure in over one-hundred developing nations worldwide.[309][310]

Peace process and de-escalation zones

.jpg.webp)

During the course of the war, there have been several international peace initiatives, undertaken by the Arab League, the United Nations, and other actors.[311] The Syrian government has refused efforts to negotiate with what it describes as armed terrorist groups.[312] On 1 February 2016, the UN announced the formal start of the UN-mediated Geneva Syria peace talks[313] that had been agreed on by the International Syria Support Group (ISSG) in Vienna. On 3 February 2016, the UN Syria peace mediator suspended the talks.[314] On 14 March 2016, Geneva peace talks resumed. The Syrian government stated that discussion of Bashar-al-Assad's presidency "is a red line", however Syria's President Bashar al-Assad said he hoped peace talks in Geneva would lead to concrete results, and stressed the need for a political process in Syria.[315]

A new round of talks between the Syrian government and some groups of Syrian rebels concluded on 24 January 24, 2017 in Astana, Kazakhstan, with Russia, Iran and Turkey supporting the ceasefire agreement brokered in late December 2016.[316] The Astana Process talks was billed by a Russian official as a complement to, rather than replacement, of the United Nations-led Geneva Process talks.[316] On 4 May 2017, at the fourth round of the Astana talks, representatives of Russia, Iran, and Turkey signed a memorandum whereby four "de-escalation zones" in Syria would be established, effective of 6 May 2017.[317][318]

On September 18, 2019, Russia stated the United States and Syrian rebels were obstructing the evacuation process of a refugee camp in southern Syria.[319]

On September 28, 2019, Syria's top diplomat demanded the foreign forces, including that of US and Turkey, to immediately leave the country, saying that the Syrian government holds the right to protect its territory in all possible ways if they remain.[320]

President RT Erdogan said Turkey was left with no choice other than going its own way on Syria 'safe zone' after deadline to co-jointly establish a "safe zone” with the US in northern Syria expired in September.[321] The U.S. indicated it will withdraw its forces from northern Syria after Turkey warned of incursion in the region that could instigate fighting with American-backed Kurds.[322]

Agreement to buffer zone on Turkish border, October 2019

In October 2019, in response to the Turkish offensive, Russia arranged for negotiations between the Syrian government in Damascus and the Kurdish-led forces.[323] Russia also negotiated a renewal of a cease-fire between Kurds and Turkey that was about to expire.[324]

Russia and Turkey made an agreement via the Sochi Agreement of 2019 to set up a Second Northern Syria Buffer Zone. Syrian President Assad expressed full support for the deal, as various terms of the agreement also applied to the Syrian government.[325][326] The SDF stated that they consider themselves as "Syrian and a part of Syria", adding that they will agree to work with the Syrian Government.[327] The SDF officially announced their support for the deal on October 27.[328][329][330]

The agreement reportedly included the following terms:[331][332][325][333][334][335]

- A buffer zone would be established in Northern Syria. The zone would be around 30 kilometres (19 mi) deep,[lower-alpha 1] stretching from Euphrates River to Tall Abyad and from Ras al-Ayn to the Iraq-Syria border, but excluding the town of Qamishli, the Kurds' de facto capital.[336]

- The buffer zone would be controlled jointly by the Syrian Army and Russian Military Police.

- All YPG forces, which constitute the majority of the SDF, must withdraw from the buffer zone entirely, along with their weapons, within 150 hours from the announcement of the deal. Their withdrawal would be overseen by Russian Military Police and the Syrian Border Guards, which would then enter the zone.

Refugees status

A major statement from NGO ACT Alliance found that millions of Syrian refugees remain displaced in countries around Syria. this includes around 1.5 million refugees in Lebanon. Also the report found that refugees in camps in north-eastern Syria have tripled this year.[337]

Numerous refugees remain in local refugee camps. Conditions there are reported to be severe, especially with winter approaching.[338][339]

4,000 people are housed at the Washokani Camp. No organizations are assisting them other than the Kurdish Red Cross. Numerous camp residents have called for assistance from international groups.[340][341]

Refugees in Northeast Syria report they have received no help from international aid organizations.[342]

On December 30, 2019, over 50 Syrian refugees, including 27 children, were welcomed in Ireland, where they started afresh in their new temporary homes at the Mosney Accommodation Centre in Co Meath. The migrant refugees were pre-interviewed by Irish officials under the Irish Refugee Protection Programme (IRPP).[343]

United Nations dispute

As of December 2019, a diplomatic dispute is occurring at the UN over re-authorization of cross-border aid for refugees. China and Russia oppose the draft resolution that seeks to re-authorize crossing points in Turkey, Iraq, and Jordan; China and Russia, as allies of Assad, seek to close the two crossing points in Iraq and Jordan, and to leave only the two crossing points in Turkey active.[344] The current authorization expires on January 10, 2020.[345]

All of the ten individuals representing the non-permanent members of the Security Council stood in the corridor outside of the chamber speaking to the press to state that all four crossing points are crucial and must be renewed.[344]

United Nations official Mark Lowcock is asking the UN to re-authorize cross-border aid to enable aid to continue to reach refugees in Syria. He says there is no other way to deliver the aid that is needed. He noted that four million refugees out of the over eleven million refugees who need assistance are being reached through four specific international crossing points. Lowcock serves as the United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator and the Head of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.[346]

Russia, aided by China's support, has vetoed the resolution to retain all four border crossings. An alternate resolution also did not pass.[347][348] The US strongly criticized the vetoes and opposition by Russia and China.[349][350]

Economic sanctions against Syria

US sanctions

The US Congress has enacted punitive sanctions on the Syrian government for its actions during the Civil War. These sanctions would penalize any entities lending support to the Syrian government, and any companies operating in Syria.[351][352][353][354] US President Donald Trump tried to protect the Turkish President Erdogan from the effect of such sanctions.[355]

Some activists welcomed this legislation.[356] Some critics contend that these punitive sanctions are likely to backfire or have unintended consequences; they argue that ordinary Syrian people will have fewer economic resources due to these sanctions (and will thus need to rely more the Syrian government and its economic allies and projects) while the sanctions' impact on ruling political elites will be limited.[351][357][358]

Mohammed al-Abdallah, Executive Director of Syria Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC), said that the sanctions will likely hurt ordinary Syrian people, saying, "it is an almost unsolvable unfeasible equation. If they are imposed, they will indirectly harm the Syrian people, and if they are lifted, they will indirectly revive the Syrian regime;" he attributed the sanctions to "political considerations, as the United States does not have weapons and tools in the Syrian file, and sanctions are its only means."[359]

Peter Ford, the former UK Ambassador to Syria, said "...going forward, we're seeing more economic warfare. It seems that the US, having failed to change the regime in Syria by military force or by proxies, is tightening the economic screws and the main reason why the US is keeping hold of the production facilities in eastern Syria. So, the economic situation is becoming more and more serious and dire in Syria and it's a major reason why refugees are not going back."

In June, US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo announced new economic sanctions on Syria targeting foreign business relations with the Syian government. Under the Caesar Act, the latest sanctions were to be imposed on 39 individuals and entities, including Asma al-Assad, wife of the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.[360]

On June 17, 2020, James F. Jeffrey, Special Representative for Syria Engagement has signalled that the UAE could soon be hit with sanctions if it pushes ahead with normalisation efforts with the Syrian regime, under Caesar Act.[361]

Syrian Constitutional Committee

In late 2019, a new Syrian Constitutional Committee began operating in order to discuss a new settlement and to draft a new constitution for Syria.[362][363] This committee comprises about 150 members. It includes representatives of the Syrian government, opposition groups, and countries serving as guarantors of the process such as e.g. Russia. However, this committee has faced strong opposition from the Assad government. 50 of the committee members represent the government, and 50 members represent the opposition.[363] It is unclear if the third round of talks will proceed on a firm schedule, until the Assad government provides its assent to participate.[363]

In December 2019, the EU held an international conference which condemned any suppression of the Kurds, and called for the self-declared Automnomous Administration in Rojava to be preserved and to be reflected in any new Syrian Constitution. The Kurds are concerned that the independence of their declared Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES) in Rojava might be severely curtailed.[364]

Status of Kurdish autonomous area in Rojava

The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES), also known as Rojava,[lower-alpha 2] is a de facto autonomous region in northeastern Syria.[368][369] The region does not state to pursue full independence but rather autonomy within a federal and democratic Syria.[370]

In March 2015, the Syrian Information Minister announced that his government considered recognizing the Kurdish autonomy "within the law and constitution".[371] While the region's administration is not invited to the Geneva III peace talks on Syria,[372] or any of the earlier talks, Russia in particular calls for the region's inclusion and does to some degree carry the region's positions into the talks, as documented in Russia's May 2016 draft for a new constitution for Syria.[373][374]

An analysis released in June 2017 described the region's "relationship with the government fraught but functional" and a "semi-cooperative dynamic".[375] In late September 2017, Syria's Foreign Minister said that Damascus would consider granting Kurds more autonomy in the region once ISIL is defeated.[376]

Depictions

Films

- Ladder to Damascus (2013)

- Sniper: Legacy (2014)

- Phantom (2015)

- The Father (2016)

- Insyriated (2017)

- Damascus Time (2018)

- A Private War (2018)

Documentaries

- The Return to Homs (2013)

- Red Lines (2014)

- Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait (2014)

- 7 Days in Syria (2015)

- 50 Feet from Syria (2015)

- Our War (2016)

- Salam Neighbor (2016)

- The War Show (2016)

- The White Helmets (2016), which won the 2017 Oscar for Best Documentary Short.

- The battle for Syria. Sources: TV air footage (video documentary + English subtitles The battle for Syria on YouTube, official video documentary and the official text of the VGTRK).[377]

- Syrian diary. Sources: TV air footage (video documentary + English subtitles Syrian diary on YouTube), official video documentary of the VGTRK.[378]

- Last Men in Aleppo (2017), nominated for Best Documentary Feature at the 90th Academy Awards.

- For Sama (2019)

- The Cave (2019)

Video games

- Endgame: Syria (2012)

- 1000 Days of Syria (2014)

- Syrian Warfare (2017)

- Holy Defence (2018)[379]

See also

Events within Syrian society

Historical aspects

Lists and statistical records

Specific offensives

- Northwestern Syria offensive (April–June 2015) ("Battle of Victory")

Peace efforts and civil society groups

History of other local conflicts

Notes

- Starting from the Syrian-Turkish border and going south into Syria.

- The name "Rojava" ("The West") was initially used by the region's PYD-led government, before its usage was dropped in 2016.[365][366][367] Since then, the name is still used by some locals and international observers.

References

- Syria-Irak-Yemen-Libya maps

- References:

- Damascus allows Iraq to hit ISIL targets in Syria: State media, Al Jazeera, Dec 30, 2018.

- Assad gives Iraq green light to launch attacks in Syria without approval, Al-Masdar News, Dec 30, 2018.

- Assad Authorizes Iraq to Attack ISIS in Syria , Haaretz, Dec 30, 2018.

- Iraqi jets strike ISIS target in Syria a day after Damascus carte blanche, The National, Dec 31, 2018.

- Iraqi Air Force bombs ISIS command meeting in Syria, Al-Masdar News, Jan 3, 2019.

- Iraq’s Air Force will begin bombing ISIS in Syria, NewsRep, Jan 1, 2019.

- "Iraq conducts first airstrikes against ISIS in Syria". CNN. 24 February 2017.

- Finn, William Maclean, Tom (27 November 2016). "Qatar will help Syrian rebels even if Trump ends U.S. role" – via www.reuters.com.

- https://ecfr.eu/special/mena-armed-groups/hayat-tahrir-al-sham-syria/

- "Trump ends CIA arms support for anti-Assad Syria rebels: U.S. officials". Reuters. 19 July 2017.

- "Victory for Assad looks increasingly likely as world loses interest in Syria". The Guardian. 31 August 2017.

Returning from a summit in the Saudi capital last week, opposition leaders say they were told directly by the foreign minister, Adel al-Jubeir, that Riyadh was disengaging.

- "Britain withdraws last of troops training Syrian rebels as world powers distance themselves from opposition". Daily Telegraph. 2 September 2017.

- "Hollande confirms French delivery of arms to Syrian rebels". AFP. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Chivers, C. J.; Schmitt, Eric; Mazzetti, Mark (21 June 2013). "In Turnabout, Syria Rebels Get Libyan Weapons". The New York Times.

- Watson, Ivan; Tuysuz, Gul (29 October 2014). "Meet America's newest allies: Syria's Kurdish minority". CNN. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- A. Jaunger (30 July 2017). "US increases military support to Kurdish-led forces in Syria". ARA News. Retrieved 1 January 2018 – via Inside Syria Media Center.

- Jamie Dettmer (9 June 2016). "France Deploys Special Forces in Syria as IS Loses Ground". VOA. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- "U.S.-backed fighters poised to cut key ISIS supply line". CBS News. 9 June 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- Irish, John (13 November 2013). "Syrian Kurdish leader claims military gains against Islamists". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

Muslim said the PYD had received aid, money and weapons from the Iraq-based Kurdistan Democratic Party and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan...

- Ranj Alaaldin (16 December 2014). "A Dangerous Rivalry for the Kurds". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

Once again, the P.U.K. saw a chance to seize the initiative, by suggesting that it, rather than the Kurdistan regional government or the K.D.P., was providing weapons and supplies to the Syrian Kurdish fighters, who belong to a party that has historically been at odds with the K.D.P.

- Jack Murphy (23 March 2017). "Did Kurdistan's Counter-Terrorist Group assault the Tabqa Dam in Syria?". SOFREP. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- Alexander Whitcomb (30 October 2014). "Peshmerga advance team in Kobane". Rudaw Media Network. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- "France Says Its Airstrikes Hit an ISIS Camp in Syria". The New York Times. 28 September 2015.

- "The UAE has it in for the Muslim Brotherhood". Al-Araby Al-Jadeed. 22 February 2017.

Along with their American counterparts, Emirati special forces are said to be training elements of the opposition. They constitute a kind of Arab guarantee among the Syrian Democratic Forces – an umbrella group dominated by the Kurds of the PYD, on whom the US are relying to fight IS on the ground.

- "Saudi Arabia, UAE send troops to support Kurds in Syria". Middle East Monitor. 22 November 2018.

- "Australia to end air strikes in Iraq and Syria, bring Super Hornets home". Reuters. 21 December 2017.

- Barton, Rosemary (26 November 2015). "Justin Trudeau to pull fighter jets, keep other military planes in ISIS fight". CBC News. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Leading Syrian regime figures killed in Damascus bomb attack". The Guardian. July 2012.

- "Syria defence minister killed in Damascus bomb". The Daily Telegraph. 18 July 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "No sign of Assad after bomb kills kin, rebels close in". Reuters. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "Syria Remains Silent on Intelligence Official's Death". The New York Times. 24 April 2015.

- "Syrian military spy chief killed in battle". al-Jazeera. 18 October 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- (Head of National Defence Forces)"Assad cousin killed in Syria's Latakia". Al Jazeera. 8 October 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Qasem Soleimani: US kills top Iranian general in Baghdad air strike". The BBC. 3 January 2020.

- "Iranian comdr. Brigadier General Hossein Hamedani killed by Isis while advising Syrian regime". The Independent. 8 October 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Iranian General Is Killed in Syria". The Wall Street Journal. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Obituary: Hezbollah military commander Mustafa Badreddine". BBC. 14 May 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Al-Nusra Front claims responsibility for Hezbollah fighters' death". Middle East Monitor. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Commander of Hezbollah Freed by Israel Is Killed in Syria". BBC. 20 December 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Thousands mourn Hezbollah fighter killed in Israeli attack". Reuters. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Analysis: Shiite Afghan casualties of the war in Syria". FDD's Long War Journal. 12 March 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Update 1-Moscow blames 'two-faced U.S. policy' for Russian general's Syria death -RIA". Reuter. 25 September 2017.

- "Body of senior Russian officer killed in Syria delivered to Moscow". TASS. 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- "Turkish Special Forces: From stopping a coup to the frontline of the ISIL fight". Hürriyet Daily News. 24 August 2016.

- sitesi, milliyet.com.tr Türkiye'nin lider haber. "Son dakika: Afrin harekatını Korgeneral İsmail Metin Temel yönetecek!". Milliyet. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "Top Syrian rebel commander dies from wounds". Reuters. 17 November 2013.

- "Leading Syrian rebel groups form new Islamic Front". BBC. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- "Suicide bombing kills head of Syrian rebel group". The Daily Star.

- "Al Qaeda's chief representative in Syria killed in suicide attack". FDD's Long War Journal. 23 February 2014.

- "Russian raids kill prominent Syrian rebel commander". Al Jazeera. 25 December 2015.

- Nic Robertson & Paul Cruickshank (5 March 2015). "Source: Syrian warplanes kill leaders of al-Nusra". CNN.

- "Senior Nusra Front commander killed in Syria air strike". Al Jazeera. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- "Nusra Front spokesman killed by air strike in Syria". Al Jazeera. 4 April 2016.

- "Syria's Qaeda spokesman, 20 jihadists dead in strikes: monitor". AFP. 3 April 2016 – via Yahoo!.

- "Air strike kills top commander of former Nusra group in Syria". Reuters. 9 September 2016.

- "Leader of Qaeda Cell in Syria, Muhsin al-Fadhli, Is Killed in Airstrike, U.S. Says". The New York Times. 2 July 2015.

- Laporta, James; O'Connor, Tom; Jamali, Naveed (26 October 2019). "Trump Approves Special Ops Raid Targeting ISIS Leader Baghdadi, Military Says He's Dead". Newsweek. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "ISIS confirms death of senior leader in Syria". FDD's Long War Journal. February 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Alessandria Masi (11 November 2014). "If ISIS Leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi Is Killed, Who Is Caliph Of The Islamic State Group?". International Business Times. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Schmidt, Michael S.; Mazzetti, Mark (25 March 2016). "A Top ISIS Leader Is Killed in an Airstrike, the Pentagon Says". The New York Times.

- Starr, Barbara (14 March 2016). "U.S. assesses ISIS operative Omar al-Shishani is dead". CNN.

- Ryan, Missy (3 July 2015). "U.S. drone strike kills a senior Islamic State militant in Syria". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Starr, Barbara; Conlon, Kevin (19 May 2015). "U.S. names ISIS commander killed in raid". CNN. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Starr, Barbara; Acosta, Jim (22 August 2015). "U.S.: ISIS No.2 killed in US drone strike in Iraq". CNN.

- Sherlock, Ruth (9 July 2014). "Inside the leadership of Islamic State: how the new 'caliphate' is run". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Isis: US-trained Tajik special forces chief Gulmurod Khalimov becomes Isis war minister". International Business Times. 6 September 2016 – via Yahoo News.

- "Top ISIL leaders killed in southern Syria". The National. 9 June 2017.

- Sands, Phil; Maayeh, Suha web (17 November 2015), "Death of 'ISIL commander' in southern Syria a blow to the group", The National

- "The Syrian Democratic Council concludes its work by issuing the final communiqué". Hawar News Agency. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "New Operation Inherent Resolve commander continues fight against ISIL". Army Worldwide News. 22 August 2016.

- "Top Syrian Kurdish commander Abu Layla killed by Isis sniper fire". The Independent. 5 June 2016.

- Hisham Arafat (31 August 2017). "Senior SDF commander lost his life in Raqqa fighting IS". Kurdistan 24.

- "Syria military strength". Global Fire Power. 8 July 2019.

- "Syria's diminished security forces". Agence France-Presse. 28 August 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ISIS’ Iraq offensive could trigger Hezbollah to fill gap left in Syria The Daily Star, 16 June 2014

- Ahmad Shuja Jamal (13 February 2018). "Mission Accomplished? What's Next for Iran's Afghan Fighters in Syria". War on the Rocks. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- "Syrian war widens Sunni-Shia schism as foreign jihadis join fight for shrines". The Guardian. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- "Iran 'Foreign Legion' Leads Battle in Syria's North". The Wall Street Journal. 17 February 2016.

- "Russia's Syria force has reportedly grown to 4,000 people". Business Insider.

- Grove, Thomas (18 December 2015). "Up to Nine Russian Contractors Die in Syria, Experts Say". Wall Street Journal.

- "State-of-the-art technology is giving Assad's army the edge in Syria". 26 February 2016.

- "Here's The Extremist-To-Moderate Spectrum Of The 100,000 Syrian Rebels". Business Insider.

- "Front to Back". Foreign Policy.

- Cockburn, Patrick (11 December 2013). "West suspends aid for Islamist rebels in Syria, underlining their disillusionment with those forces opposed to President Bashar al-Assad". The Independent.

- Who are these 70,000 Syrian fighters David Cameron is relying on?. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Şafak, Yeni (5 January 2017). "8 bin asker emir bekliyor". Yeni Şafak.

- "US Assistant Secretary of Defense tells Turkey only ISIS is a target, not Kurds". ARA News. 16 January 2017.

- "Is Syria's Idlib being groomed as Islamist killing ground?". Asia Times.

- "Al Qaeda Is Starting to Swallow the Syrian Opposition". Foreign Policy. 15 March 2017.

- Stewart, Phil (4 September 2018). "Top U.S. general warns against major assault on Syria's Idlib". Reuters.

- Rida, Nazeer (30 January 2017). "Syria: Surfacing of 'Hai'at Tahrir al-Sham' Threatens Truce". Asharq Al-Awsat.

- "IS 'caliphate' defeated but jihadist group remains a threat". BBC. 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Rashid (2018), p. 7.

- Rashid (2018), p. 16.

- Rashid (2018), p. 53.

- "US coalition spokesman: Arabs are leading Manbij campaign, not Kurds". ARA News. 4 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- "US-backed fighters close in on IS Syria bastion". AFP. 6 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Rodi Said (25 August 2017). "U.S.-backed forces to attack Syria's Deir al-Zor soon: SDF official". Reuters.

- Sisk, Richard (10 November 2019). "Up to 600 Troops Now Set to Remain in Syria Indefinitely, Top General Says". Military.com.

- "On International Human Rights Day: Millions of Syrians robbed of "rights" and 593 thousand killed in a decade". SOHR. 9 December 2020.

- "Tantalizing promises of Bashar al- Assad kill more than 11000 fighters of his forces during 5 months". SOHR. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "On Balance, Hezbollah Has Benefited from the Syrian Conflict". The Soufan Group. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- "Syria Daily: Russia Acknowledges Deaths of 3 Troops". 26 March 2019.

- 151–201 killed (2015-17), 14–64 killed (Battle of Khasham, Feb. 2018), 18 killed (May 2018-June 2019), total of 183–283 reported dead

- "IRGC Strategist Hassan Abbasi Praises Iranian Parents Who Handed Over Their Oppositionist Children For Execution: Educating People To This Level Is The Pinnacle Of The Islamic Republic's Achievement; Adds: 2,300 Iranians Have Been Killed In Syria War". MEMRI.

- الشامية, محرر الدرر (30 August 2017). "عميد إيراني يكشف عن إحصائية بأعداد قتلى بلاده في سوريا". الدرر الشامية. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- 72 killed in Operation Euphrates Shield, 61–96 killed in Operation Olive Branch, 67–81 killed in Idlib buffer zone, 16 killed in Operation Peace Spring, 11–17 killed in post-OPS operations, 1 killed in post-OES operations, total of 228–283 reported killed (for more details see here)

- "Pilot killed as U.S. F-16 crashes in Jordan".

"Jordan pilot murder: Islamic State deploys asymmetry of fear". BBC News. 4 February 2015.

"US service member killed in Syria identified as 22-year-old from Georgia". ABC News. 27 May 2017.

"US identifies American service member killed by IED in Syria". ABC News. 27 May 2017.

"French soldier killed in Iraq-Syria military zone, Élysée Palace says". France24. 27 May 2017.

"4 Americans among those killed in Syria attack claimed by ISIS". CNN. 27 May 2017.

"Mystery surrounds the killing of a US soldier in the countryside of Ayn al-Arab (Kobani) amid accusations against Turkey of targeting him". Syrian Observatory of Human Rights. 2 May 2019.

"US service member killed in Syria identified as 22-year-old from Georgia". ABC News. 27 May 2017.

"Army identifies U.S. soldier killed in Syria". The Washington Times. 27 January 2020.

"Pentagon identifies US soldier killed in Syria". The Hill. 23 July 2020. - "Violations Documenting Center". Violations Documenting Center. 23 February 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- (UNHCR), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response".

- Thomas Gibbons-Neff (16 September 2016). "U.S. Special Operations forces begin new role alongside Turkish troops in Syria". The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Andrew Tilghman (16 November 2016). "U.S. halts military support for Turkey's fight in key Islamic State town". Military Times. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- Fadel, Leith (27 September 2016). "US Coalition knew they were bombing the Syrian Army in Deir Ezzor".