Arabization

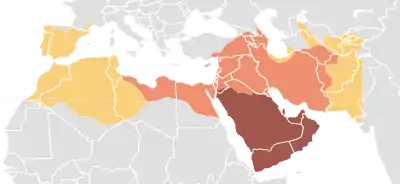

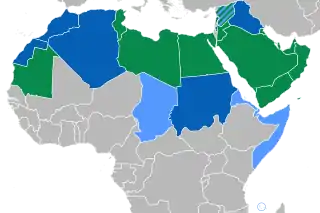

Arabization or Arabisation (Arabic: تعريب taʻrīb) describes both the process of growing Arab influence on non-Arab populations, causing a language shift by their gradual adoption of the Arabic language and their incorporation of the culture, as well as the Arab nationalist policies of some governments in modern Arab countries toward non-Arab minorities, including Lebanon, Iraq,[1] Syria, Sudan,[2] Mauritania, Algeria,[2] Libya, and (when it governed territory) the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

.jpg.webp)

Historically, aspects of the culture of the Arabian Peninsula were combined in various forms with the cultures of conquered regions and ultimately denominated "Arab". After the rise of Islam in the Hejaz, Arab culture and language were spread outside the Arabian Peninsula through conquest, trade and intermarriages between members of the non-Arab local population and the peninsular Arabs. The Arabic language began to serve as a lingua franca in these areas and dialects were formed. Although Yemen is traditionally held to be the homeland of the Qahtanite Arabs who, according to Arab tradition, are pure Arabs, most of the Yemeni population in fact did not speak Old Arabic prior to the spread of Islam, but Old South Semitic languages instead.[3][4]

The influence of Arabic has been profound in many other countries whose cultures have been influenced by Islam. Arabic was a major source of vocabulary for various languages. This process reached its zenith between the 10th and 14th centuries, the high point of Arab culture.

Early Arab expansion in the Near East

After Alexander the Great, the Nabataean kingdom emerged and ruled a region extending from north of Arabia to the south of Syria. the former originating from the Arabian peninsula, who came under the influence of the earlier Aramaic culture, the neighbouring Hebrew culture of the Hasmonean kingdom, as well as the Hellenistic cultures in the region (especially with the Christianization of Nabateans in 3rd and 4th centuries). The pre-modern Arabic language was created by Nabateans, who developed the Nabataean alphabet which became the basis of modern Arabic script. The Nabataean language, under heavy Arab influence, amalgamated into the Arabic language.

The Arab Ghassanids were the last major non-Islamic Semitic migration northward out of Yemen in late classic era. They were Greek Orthodox Christian, and clients of the Byzantine Empire. They arrived in Byzantine Syria which had a largely Aramean population. They initially settled in the Hauran region, eventually spreading to entire Levant (modern Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan), briefly securing governorship of parts of Syria and Transjordan away from the Nabataeans.

The Arab Lakhmid Kingdom was founded by the Lakhum tribe that emigrated from Yemen in the 2nd century and ruled by the Banu Lakhm, hence the name given it. They adopted the religion of the Church of the East, founded in Assyria/Asōristān, opposed to the Ghassanids Greek Orthodox Christianity, and were clients of the Sasanian Empire.

The Byzantines and Sasanians used the Ghassanids and Lakhmids to fight proxy wars in Arabia against each other.

History of Arabization

Arabization during the early Caliphate

The earliest and most significant instance of "Arabization" was the early Muslim conquests of Muhammad and the subsequent Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates. They built a Muslim Empire that grew well beyond the Arabian Peninsula, eventually reaching as far as Spain in the West and Central Asia to the East.

Southern Arabia

South Arabia is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it also included Najran, Jizan, and 'Asir, which are presently in Saudi Arabia, and the Dhofar of present-day Oman.

Old South Arabian was driven to extinction by the Islamic expansion, being replaced by Classical Arabic which is written with the Arabic script. The South Arabian alphabet which was used to write it also fell out of use. A separate branch of south semitic, the Modern South Arabian languages still survive today as spoken languages in southern of present-day Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Dhofar in present-day Oman.

Although Yemen is traditionally held to be the homeland of Arabs, most[5][6] of the sedentary Yemeni population did not speak Arabic (but instead Old South Arabian languages) prior to the spread of Islam.

Eastern Arabia

The sedentary people of pre-Islamic Eastern Arabia were mostly Aramaic speakers and to some degree Persian speakers, while Syriac functioned as a liturgical language.[7][8] According to Serjeant, the indigenous Bahrani people are the Arabized "descendants of converts from the original population of Christians (Aramaeans), Jews and ancient Persians (Majus) inhabiting the island and cultivated coastal provinces of Eastern Arabia at the time of the Arab conquest".[9] In pre-Islamic times, the population of eastern Arabia consisted of partially Christianized Arabs, Aramean agriculturalists and, Persian-speaking Zoroastrians.[10][7][9]

Zorastarianism was one of the major religions of pre-Islamic eastern Arabia; the first monotheistic religion in the history of eastern Arabia were known as Majoos in pre-Islamic times.[11]

The Fertile Crescent and Syria (region)

After the rise of Islam, the Arab tribes unified under the banner of Islam and conquered modern Jordan, Israel, Palestinian territories, Iraq and Syria. However, even before the emergence of Islam, the Levant was already a home for several pre-Islamic Arabian kingdoms. The Nabateans kingdom of Petra which was based in Jordan, the Ghassanids kingdom which was based in the Syrian desert. Some of these kingdoms were under the indirect influence of the Romans, Byzantines, and the Persian Sassanids. The Nabateans transcript developed in Petra was the base for the current Arabic transcript while the Arab heritage is full of poetry recording the wars between the Ghassanids and Lakhmids Arabian tribes in Syria. In the 7th century, and after the dominance of Arab Muslims within a few years, the major garrison towns developed into the major cities. The local Arabic and Aramaic speaking population, which shared a very close Semitic linguistic/genetic ancestry with the Qahtani and Adnani Arabs, was somewhat Arabized. The indigenous Assyrians largely resisted Arabization in Upper Mesopotamia, the Assyrians of the north continued to speak Akkadian influenced Neo-Aramaic dialects descending from the Imperial Aramaic of the Assyrian Empire, together with Syriac which was founded in Assyria in the 5th century BC, and retaining Assyrian Church of the East and Syriac Orthodox Church Christianity. These linguistic and religious traditions still persist to the present day. The Gnostic Mandeans also retained their ancient culture, religion and Mandaic-Aramaic language after the Arab Islamic conquest, and these too still survive today.

Egypt

Since the foundation of the Ptolemaic kingdom in Alexandria, Egypt had been under the influence of Greek culture. Before Alexander the Great it had been ruled by the Achaemenid Empire. Greek influence remained strong after Egypt's conquest by the Roman Empire in 30BC. Eventually it was conquered from the Eastern Romans by the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate in the 7th century CE. The Coptic language, which was written using the Coptic variant of the Greek alphabet, was spoken in Egypt before the Islamic conquest. As a result of Egypt's cultural Arabization, the adopted Arabic language began to serve as a lingua franca. The Egyptian Arabic dialect has retained a number of Coptic words, and the grammar takes some influence from Coptic, as well. Currently the Ancient Coptic language only survives as a liturgical language of the Coptic Church and is fluently spoken by many Egyptian priests.

North Africa and Iberia

Neither North Africa nor the Iberian Peninsula were strangers to Semitic culture: the Phoenicians and later the Carthaginians dominated parts of the North African and Iberian shores for more than eight centuries until they were suppressed by the Romans and by the following Vandal and Visigothic invasions, and the Berber incursions. After the Arab invasion of North Africa, The Berber tribes allied themselves with the Umayyad Arab Muslim armies in invading the Iberian Peninsula. Later, in 743 AD, the Berbers defeated the Arab Umayyad armies and expelled them for most of West North Africa (al-Maghreb al-Aqsa) during the Berber Revolt, but not the territory of Ifriqiya which stayed Arab (East Algeria, Tunisia, and West-Libya). Centuries later some migrating Arab tribes settled in some plains while the Berbers remained the dominant group mainly in desert areas including mountains. The Inland North Africa remained exclusively Berber until the 11th century; the Iberian Peninsula, on the other hand, remained Arabized, particularly in the south, until the 16th century.

After finishing the establishment of the Arab city of Al Mahdiya in Tunisia and spreading the Islamic Shiite faith, some of the many Arab Fatimids left Tunisia and parts of eastern Algeria to the local Zirids (972–1148).[12] The invasion of Ifriqiya by the Banu Hilal, a warlike Arab Bedouin tribe encouraged by the Fatimids of Egypt to seize North Africa, sent the region's urban and economic life into further decline.[12] The Arab historian Ibn Khaldun wrote that the lands ravaged by Banu Hilal invaders had become completely arid desert.[13][14]

Arabization in Islamic Iberia

After the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, under the Arab Muslim rule Iberia (al-Andalus) incorporated elements of Arabic language and culture. The Mozarabs were Iberian Christians who lived under Arab Islamic rule in Al-Andalus. Their descendants remained unconverted to Islam, but did however adopt elements of Arabic language and culture and dress. They were mostly Roman Catholics of the Visigothic or Mozarabic Rite. Most of the Mozarabs were descendants of Hispano–Gothic Christians and were primarily speakers of the Mozarabic language under Islamic rule. Many were also what the Arabist Mikel de Epalza calls "Neo-Mozarabs", that is Northern Europeans who had come to the Iberian Peninsula and picked up Arabic, thereby entering the Mozarabic community.

Besides Mozarabs, another group of people in Iberia eventually came to surpass the Mozarabs both in terms of population and Arabization. These were the Muladi or Muwalladun, most of whom were descendants of local Hispano-Basques and Visigoths who converted to Islam and adopted Arabic culture, dress, and language. By the 11th century, most of the population of al-Andalus was Muladi, with large minorities of other Muslims, Mozarabs, and Sephardic Jews. It was the Muladi, together with the Berber, Arab, and other (Saqaliba and Zanj) Muslims who became collectively termed in Christian Europe as "Moors".

The Andalusian Arabic language was spoken in Iberia during Islamic rule.

Arabization in Islamic Sicily, Malta, and Crete

A similar process of Arabization and Islamization occurred in the Emirate of Sicily (as-Siqilliyyah), Emirate of Crete (al-Iqritish), and Malta (al-Malta), albeit for a much shorter time span than al-Andalus. However, this resulted in the now defunct Sicilian Arabic language to develop, from which the modern Maltese language derives.

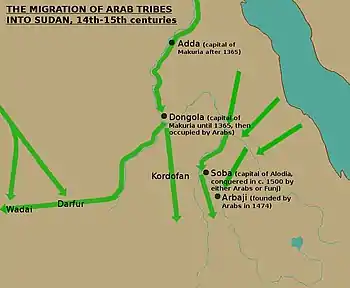

Arabization in Sudan

In the 12th century, the Arab Ja'alin tribe migrated into Nubia and Sudan and formerly occupied the country on both banks of the Nile from Khartoum to Abu Hamad. They trace their lineage to Abbas, uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. They are of Arab origin, but now of mixed blood mostly with Northern Sudanese and Nubians.[15][16] They were at one time subject to the Funj kings, but their position was in a measure independent. Johann Ludwig Burckhardt said that the true Ja'alin from the eastern desert of Sudan are exactly like the Bedouin of eastern Arabia.

In 1846, many Arab Rashaida migrated from Hejaz in present-day Saudi Arabia into what is now Eritrea and north-east Sudan after tribal warfare had broken out in their homeland. The Rashaida of Sudan and Eritrea live in close proximity with the Beja people. Large numbers of Bani Rasheed are also found on the Arabian Peninsula. They are related to the Banu Abs tribe.[17] The Rashaida speak Hejazi Arabic.

In 1888, the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain claimed that the Arabic spoken in Sudan was "a pure but archaic Arabic". The pronunciation of certain letters was like Syrian and Khaleeji Arabic, and not like the Egyptian Arabic which is very different from both. In Sudanese Arabic, the g letter is being the pronunciation for Kaph and J letter is being the pronunciation for Jim.[18]

Arabization in Sahel

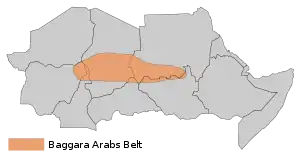

In Medieval times, the Baggara Arabs a grouping of Arab ethnic groups who speak Shuwa Arabic (which is one of the regional varieties of Arabic in Africa) migrated into Africa, mainly between Lake Chad and southern Kordofan.

Currently, they live in a belt stretching across Sudan, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic and South Sudan and numbering over six million people. Like other Arabic speaking tribes in the Sahara and the Sahel, Baggara tribes have origin ancestry from the Juhaynah Arab tribes who migrated directly from the Arabian peninsula or from other parts of north Africa. [19]

Arabic is an official language of Chad and Sudan as well as a national language in Niger, Mali, Senegal and South Sudan. In addition, Arabic dialects are spoken of minorities in Nigeria, Cameroon and Central African Republic.

Arabization in modern times

Arabization in Algeria

Arabization is the process of developing and promoting Arabic into a nation's education system, government, and media in order to replace a former language that was enforced into a nation due to colonization.[20] Algeria had been conquered by France and even made to be part of its metropolitan core for 132 years, a significantly longer timespan compared to Morocco and Tunisia, and it was also more influenced by Europe due to the contiguity with French settlers in Algeria: both Algerian and French nationals used to live in the same towns, resulting in the cohabitation of the two populations.[21] Based on these facts, one might be induced to believe that Algeria's Arabization process would have been the hardest to achieve, but on the contrary it was the smoothest in the Maghreb region. While trying to build an independent and unified nation-state after the Evian Accords, the Algerian government under Ahmed Ben Bella’s rule began a policy of “Arabization”. Indeed, due to the lasting and deep colonization, French was the major administrative and academic language in Algeria, even more so than in neighboring countries. The unification and pursuit of a single Algerian identity was to be found in the Arab language and religion, as stated in the 1963 constitution: La langue arabe est la langue nationale et officielle de l’État ("Arabic is the national and official state language") and L'islam est la religion de l'État [...] ("Islam is the state religion") and confirmed in 1969, 1976, 1989, 1996 and 2018. According to Abdelhamid Mehri, the decision of Arabic as an official language was the natural choice for Algerians,[22] even though Algeria is a plurilingual nation with a minority, albeit substantial, number of Berbers within the nation, and the local variety of Arabic used in every-day life was distinct from MSA Arabic. However, the process of Arabization was meant not only to promote Islam, but to fix the gap and decrease any conflicts between the different Algerian ethnic groups and promote equality through monolingualism.[23] In 1964 the first practical measure was the Arabization of primary education and the introduction of religious education, the state relying on Egyptian teachers – belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood and therefore particularly religious[24] – due to its lack of literary Arabic-speakers. In 1968, during the Houari Boumediene regime, Arabization was extended, and a law[25] tried to enforce the use of Arabic for civil servants, but again, the major role played by French was only diminished. Many laws followed, trying to ban French, Algerian Arabic and Berber from schools, administrative acts and street signs, but this revived Berber opposition to the state and created a distinction between those educated in Arabic and those in French, the latter still being favored by elites.

The whole policy was ultimately not as effective as anticipated: French had kept its importance[26] and Berber opposition kept growing, contributing to the 1988 October Riots. Some Berber groups, like the Kabyles, felt that their ancestral culture and language were threatened and the Arab identity was given more focus at the expense of their own. After the Algerian Civil War, the government tried to enforce even more the use of Arabic,[27] but the relative effect of this policy after 1998 (the limit fixed for complete Arabization) forced the heads of state to make concessions towards Berber, recognizing it in 2002[28] as another national language that will be promoted. However, because of literary Arabic's symbolic advantage, as well as being a single language as opposed to the fragmented Berber languages, Arabization is still a goal for the state, for example with laws on civil and administrative procedures.[29]

After the Algerian school system completed its transition to Arabic in 1989, James Coffman made a study of the difference between Arabized and non-Arabized students at the Université des Sciences et de la Technologie Houari Boumediene (USTHB) and at the University of Algiers. Interviewing students he found

Arabized students show decidedly greater support for the Islamist movement and greater mistrust of the West. Arabized students tend to repeat the same ... stories and rumors that abound in the Arabic-language press, particularly Al-Munqidh, the newspaper of the Islamic Salvation Front. They tell about sightings of the word "Allah" written in the afternoon sky, the infiltration into Algeria of Israeli women spies infected with AIDS, the "disproving" of Christianity on a local religious program,[30] and the mass conversion to Islam by millions of Americans. ... When asked if the new, Arabized students differed from the other students, many students and faculty answered an emphatic yes.[31]

Arabization in Morocco

Following 44 years of colonization by France,[21] Morocco began promoting the use of Arabic (MSA Arabic) to create a united Moroccan national identity, and increase literacy throughout the nation away from any predominant language within the administration and educational system. Unlike Algeria, Morocco did not encounter with the French as strongly due to the fact that the Moroccan population was scattered throughout the nation and major cities, which resulted in a decrease of French influence compared to the neighboring nations.[21] According to these facts, one could consider that Morocco would lay an easier path to Arabization and attain it at a faster rate than its neighboring country Algeria, although the results were on the contrary. First and foremost, educational policy was the main focus within the process, debates surfaced between officials who preferred a "modern and westernized" education with enforcement of bilingualism while others fought for a traditional route with a focus of "Arabo-Islamic culture".[32] Once the Istiqal Party took power, the party focused on placing a language policy siding with the traditional ideas of supporting and focusing on Arabic and Islam.[32] The Istiqal Party implemented the policy rapidly and by the second year after gaining independence, the first year of primary education was completely Arabized, and a bilingual policy was placed for the remaining primary education decreasing the hours of French being taught in a staggered manner.[32] Arabization in schools had been more time-consuming and difficult than expected due to the fact that the first 20 years following independence, politicians (most of which were educated in France or French private school in Morocco) were indecisive as to if Arabization was best for the country and its political and economic ties with European nations.[21] Regardless, complete Arabization can only be achieved if Morocco becomes completely independent from France in all aspects; politically, economically, and socially. Around 1960, Hajj Omar Abdeljalil the education minister at the time reversed all the effort made to Arabize the public school and reverted to pre-independent policies, favoring French and westernized learning.[21] Another factor that reflected the support of reversing the Arabization process in Morocco, was the effort made by King Hassan II, who supported the Arabization process but in contrary increased political and economic dependence with France.[21] Due to the fact that Morocco remained dependent to France and wanted to keep strong ties with the western world, French was supported by the elites more than Arabic for the development of Morocco.[21]

Arabization in Tunisia

The Arabization process in Tunisia theoretically should have been the easiest within the North African region because it has less than 1% of Berber speaking population, and practically 100% of the nation is a native Tunisian Darija speaker.[21][33] Although, it was the least successful due to its dependence on European nations and belief in westernizing the nation for future development of the people and the country. Much like Morocco, Tunisian leaders' debate consumed of traditionalists and modernists, traditionalists claiming that Arabic (specifically Classical Arabic) and Islam are the core of Tunisia and its national identity, while modernists believed that westernized development distant from "Pan- Arabist ideas" are crucial for Tunisia's progress.[33] Modernists had the upper hand, considering elites supported their ideals, and after the first wave of graduates that had passed their high school examinations in Arabic were not able to find jobs nor attend a university because they did not qualify due to French preference in any upper-level university or career other than Arabic and Religious Studies Department.[33] There were legitimate efforts made to Arabize the nation from the 1970s up until 1982, though the efforts came to an end and the process of reversing all the progress of Arabization began and French implementation in schooling took effect.[33] The Arabization process was criticized and linked with Islamic extremists, resulting in the process of "Francophonie" or promoting French ideals, values, and language throughout the nation and placing its importance above Arabic.[33] Although Tunisia gained its independence, nevertheless the elites supported French values above Arabic, the answer to developing an educated and modern nation, all came from westernization. The constitution stated that Arabic was the official language of Tunisia but nowhere did it claim that Arabic must be utilized within the administrations or every-day life, which resulted in an increase of French usage not only in science and technology courses, but major media channels were French, and government administrations were divided while some were in Arabic others were in French.[33]

Arabization in Sudan

Sudan is an ethnically-mixed country that is economically and politically dominated by the society of central northern Sudan, where many strongly identify as Arabs and Muslims. The population in southern Sudan consists mostly of Christian and Animist Nilotic people. The Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005) is typically characterized as a conflict between these two groups of people. In the 2011 Southern Sudanese independence referendum, the latter voted for secession and became independent.

The unrelated War in Darfur was an uprising in the western Darfur region of Sudan, caused by oppression of Darfur's non-Arab Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit ethnic groups.[34][35] The Sudanese government responded to the armed resistance by carrying out a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Darfur's non-Arabs. This resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians, in mass displacements and coercive migrations, and in the indictment of Sudan's president Omar al-Bashir for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court.[36] Former US Secretary of State Colin Powell described the situation as a genocide or acts of genocide.[37] The perpetrators were Sudanese military and police and the Janjaweed, a Sudanese militia group recruited mostly among arabized indigenous Africans and a small number of Bedouin of the northern Rizeigat.[38][39][40][41]

Arabization in Mauritania

Mauritania is an ethnically-mixed country that is economically and politically dominated by those who identify as Arabs and/or Arabic-speaking Berbers. About 30% of the population is considered "Black African", and the other 40% are Arabized Blacks, both groups suffer high levels of discrimination.[42] Recent Black Mauritanian protesters have complained of "comprehensive Arabization" of the country.[43]

Arabization in Iraq

Saddam Hussein's Ba'ath Party had aggressive Arabization policies involving driving out many pre-Arab and non-Arab races – mainly Kurds, Assyrians, Yezidis, Shabaks, Armenians, Turcomans, Kawliya, Circassians and Mandeans – replacing them with Arab families.

In the 1970s, Saddam Hussein exiled between 350,000 to 650,000 Shia Iraqis of Iranian ancestry (Ajam).[44] Most of them went to Iran. Those who could prove an Iranian/Persian ancestry in Iran's court received Iranian citizenship (400,000) and some of them returned to Iraq after Saddam.[44]

During the Iran-Iraq War, the Anfal campaign destroyed many Kurdish, Assyrian and other ethnic minority villages and enclaves in North Iraq, and their inhabitants were often forcibly relocated to large cities in the hope that they would be Arabized.

This policy drove out 500,000 people in the years 1991–2003. The Baathists also pressured many of these ethnic groups to identify as Arabs, and restrictions were imposed upon their languages, cultural expression and right to self-identification.

Arabization in Syria

Since the independence of Syria in 1946, the ethnically diverse Rojava region in northern Syria suffered grave human rights violations, because all governments pursued a most brutal policy of Arabization.[45] While all non-Arab ethnic groups within Syria, such as Assyrians, Armenians, Turcomans and Mhallami have faced pressure from Arab Nationalist policies to identify as Arabs, the most archaic of it was directed against the Kurds. In his report for the 12th session of the UN Human Rights Council titled Persecution and Discrimination against Kurdish Citizens in Syria, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights held:[46] "Successive Syrian governments continued to adopt a policy of ethnic discrimination and national persecution against Kurds, completely depriving them of their national, democratic and human rights — an integral part of human existence. The government imposed ethnically-based programs, regulations and exclusionary measures on various aspects of Kurds’ lives — political, economic, social and cultural."

The Kurdish language was not officially recognized, it had no place in public schools.[45][46][47] A decree from 1989 prohibited the use of Kurdish at the workplace as well as in marriages and other celebrations. In September 1992 another government decree that children be registered with Kurdish names.[48] Also businesses could not be given Kurdish names.[45][46] Books, music, videos and other material could not be published in Kurdish language.[45][47] Expressions of Kurdish identity like songs and folk dances were outlawed[46][47] and frequently prosecuted under a purpose-built criminal law against "weakening national sentiment".[49] Celebrating the Nowruz holiday was often constrained.[45][47]

In 1973 the Syrian authorities confiscated 750 square kilometers of fertile agricultural land in Al-Hasakah Governorate, which were owned and cultivated by tens of thousands of Kurdish citizens, and gave it to Arab families brought in from other provinces.[46][50] In 2007 in another such scheme in Al-Hasakah governate, 6,000 square kilometers around Al-Malikiyah were granted to Arab families, while tens of thousands of Kurdish inhabitants of the villages concerned were evicted.[46] These and other expropriations of ethnic Kurdish citizens followed a deliberate masterplan, called "Arab Belt initiative", attempting to depopulate the resource-rich Jazeera of its ethnic Kurdish inhabitants and settle ethnic Arabs there.[45]

After the Turkish-led forces had captured Afrin District in early 2018, they began to implement a resettlement policy by moving Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army fighters and Sunni Arab refugees from southern Syria into the empty homes that belonged to displaced locals.[51] The previous owners, most of them Kurds or Yazidis, were often prevented from returning to Afrin.[51] Refugees from Eastern Ghouta, Damascus, said that they were part of "an organised demographic change" which was supposed to replace the Kurdish population of Afrin with an Arab majority.[51]

Arabization in Islamic State of Iraq and Levant campaign

While formally committed to Islamism and polyethnicity, the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL) has frequently targeted non-Arab groups such as such as Kurds, Assyrians, Armenians, Turcomans, Shabaks and Yezidis.[52][53] It has often been claimed that these (ISIL) campaigns were a part of an organized Arabization plan.[52][53] A Kurdish official in Iraqi Kurdistan claimed that in particular the ISIL campaign in Sinjar was a textbook case of Arabization.[54]

It has been suggested in academia that modern Islamism in general and the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL) in particular would be motivated and driven by a desire to reinforce Arab cultural dominion over the religion of Islam.[55]

Reversing Arabization

Invasion of Malta (1091)

The invaders besieged Medina (modern Mdina), the main settlement on the island, but the inhabitants managed to negotiate peace terms. The Muslims freed Christian captives, swore an oath of loyalty to Roger and paid him an annual tribute. Roger's army then sacked Gozo and returned to Sicily with the freed captives.

The attack did not bring about any major political change, but it paved the way for the re-Christianization of Malta, which began in 1127. Over the centuries, the invasion of 1091 was romanticized as the liberation of Christian Malta from oppressive Muslim rule, and a number of traditions and legends arose from it, such as the unlikely claim that Count Roger gave his colours red and white to the Maltese as their national colours.

Reconquista (1212-1492)

The Reconquista in the Iberian Peninsula is the most notable example for a historic reversion of Arabization. The process of Arabization and Islamization was reversed as the mostly Christian kingdoms in the north of the peninsula conquered Toledo in 1212 and Cordoba in 1236.[56] As Granada was conquered in January 1492 also the last remaining Emirate on the Peninsula was conquered.[57] The re-conquered territories later were Romanized and Christianized, although the culture, languages and religious traditions imposed differed from those of the previous Visigothic kingdom.

Reversions in modern times

In modern times, there have been various political developments to reverse the process of Arabization. Notable among these are:

- The 1929 introduction of the Latin Alphabet instead of the Arabic Abjad in Turkey as part of the Kemalist reforms.

- The 1992 establishment of Kurdish-dominated polity in the Mesopotamia as Iraqi Kurdistan.

- The 2012 establishment of multi-ethnic Democratic Federation of Northern Syria.[58]

- Berberism, a Berber political-cultural movement of ethnic, geographic, or cultural nationalism present in Algeria, Morocco and broader North Africa including Mali. The Berberist movement is in opposition to Islamist-driven cultural Arabization and the pan-Arabist political ideology and also associated with secularism.

- Arabization of Malays was criticized by Sultan Ibrahim Ismail of Johor.[59] He urged the retention of Malay culture instead of introducing Arab culture.[60] He called on people to not mind unveiled women, mixed sex handshaking and to using Arabic words in place of Malay words.[61] He suggested Saudi Arabia as a destination for those who wanted Arab culture.[62][63] He said that he was going to adhere to Malay culture himself.[64][65] Abdul Aziz Bari said that Islam and Arab culture are intertwined and criticized the Johor Sultan for what he said.[66] Datuk Haris Kasim also criticized the Sultan for his remarks, he leads the Selangor Islamic Religious Department.[67]

See also

Notes

- Iraq, Claims in Conflict: Reversing Ethnic Cleansing in Northern Iraq.

- Reynolds, Dwight F. (2 April 2015). The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521898072.

- Nebes, Norbert, "Epigraphic South Arabian," in Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 335

- Leonid Kogan and Andrey Korotayev: Sayhadic Languages (Epigraphic South Arabian) // Semitic Languages. London: Routledge, 1997, p[. 157-183.

- Nebes, Norbert, "Epigraphic South Arabian," in Uhlig, Siegbert, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005), p. 335

- Leonid Kogan and Andrey Korotayev: Sayhadic Languages (Epigraphic South Arabian) // Semitic Languages. London: Routledge, 1997, pp. 157-183.

- Smart, J. R.; Smart, J. R. (2013). Tradition and Modernity in Arabic Language And Literature. J R Smart, J. R. Smart. ISBN 9781136788123.

- Cameron, Averil (1993). The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity. Averil Cameron. p. 185. ISBN 9781134980819.

- Holes, Clive (2001). Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia: Glossary. Clive Holes. pp. XXIV–XXVI. ISBN 9004107630.

- Houtsma, M. Th (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 5. M. Th. Houtsma. p. 98. ISBN 9004097910.

- Zanaty, Anwer Mahmoud. "Glossary Of Islamic Terms". Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Stearns, Peter N.; Leonard Langer, William (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged (6 ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 129–131. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

- Singh, Nagendra Kr (2000). International encyclopaedia of islamic dynasties. 4: A Continuing Series. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. pp. 105–112. ISBN 81-261-0403-1.

- "Populations Crises and Population Cycles, Claire Russell and W.M.S. Russell". Galtoninstitute.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 103.

- Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization) (1888). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17. p. 16. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- "Eritrea: The Rashaida People". Madote.com. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization) (1888). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17. p. 11. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- deWaal and Flint 2006, pp. 9.

- Daoud, Mohamed (30 June 1991). "Arabization in Tunisia: The Tug of War". Issues in Applied Linguistics. 2 (1): 7–29.

- Sirles, Craig A. (1 January 1999). "Politics and Arabization: the evolution of postindependence North Africa". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 137 (1). doi:10.1515/ijsl.1999.137.115. ISSN 0165-2516. S2CID 145218630.

- Mehri, Abdelhamid (January 1972). "Arabic language takes back its place". Le Monde Diplomatique.

- Benrabah, Mohamed (10 August 2010). "Language and Politics in Algeria". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 10: 59–78. doi:10.1080/13537110490450773. S2CID 144307427.

- Abu-Haidar, Farida. 2000. ‘Arabisation in Algeria’. International Journal of Francophone Studies 3 (3): 151–163.

- ordonnance n° 68-92 du 26 avril rendant obligatoire, pour les fonctionnaires et assimilés, la connaissance de la langue nationale (1968)

- Benrabah, Mohamed. 2007. ‘Language Maintenance and Spread: French in Algeria’. International Journal of Francophone Studies 10 (1–2): 193–215

- http://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/afrique/algerie_loi-96.htm

- article 3bis in the 2002 constitutional revision

- loi du 25 fevrier 2008 Bttp://www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca/afrique/algerie_loi-diverses.htm#Loi_n°_08-09_du_25_février_2008_portant_code_de_procédure_civile_et_administrative_

- When Ahmed Deedat, a South African Muslim scholar, debated Jimmy Swaggart (described as the "leader of Christianity") on the veracity of the Bible. Swaggart was widely believed to have been "trounced", and to have admitted that the Bible had been altered throughout history. "For many millions of Algerians, this constituted proof of the superiority of Islam over Christianity".

- Coffman, James (December 1995). "Does the Arabic Language Encourage Radical Islam?". Middle East Quarterly. 2 (4): 51–57. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- Redouane, Rabia (May 1998). "Arabisation in the Moroccan Educational System: Problems and Prospects". Language, Culture and Curriculum. 11 (2): 195–203. doi:10.1080/07908319808666550. ISSN 0790-8318.

- Daoud, Mohamed (30 June 1991). Arabization in Tunisia: The Tug of War. eScholarship, University of California. OCLC 1022151126.

- "Q&A: Sudan's Darfur conflict". BBC News. 8 February 2010. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- "Reuters AlertNet – Darfur conflict". Alertnet.org. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- "The Prosecutor v. Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir". International Criminal Court. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- Adam Jones (27 September 2006). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. p. 373. ISBN 978-1-134-25980-9.

- de Waal, Alex (25 July 2004). "Darfur's Deep Grievances Defy All Hopes for An Easy Solution". The Observer. London. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- "Rights Group Says Sudan's Government Aided Militias". Washington Post. 20 July 2004. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- "Darfur – Meet the Janjaweed". American Broadcasting Company. 3 June 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia, Sudan, one-sided conflict, Janjaweed – civilians Archived 22 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 2 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Alicia Koch, Patrick K. Johnsson (8 April 2010). "Mauritania: Marginalised Black populations fight against Arabisation - Afrik-news.com : Africa news, Maghreb news - The African daily newspaper". Afrik-news.com. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- "Hamshahri Newspaper (In Persian)". hamshahri.org. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "SYRIA: The Silenced Kurds; Vol. 8, No. 4(E)". Human Rights Watch. 1996.

- "Persecution and Discrimination against Kurdish Citizens in Syria, Report for the 12th session of the UN Human Rights Council" (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2009.

- Tejel, Jordi; Welle, Jane (2009). Syria's kurds history, politics and society (PDF) (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. pp. X. ISBN 978-0-203-89211-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Gunter, Michael M. (2014). Out of Nowhere: The Kurds of Syria in Peace and War. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 9781849044356.

- "HRW World Report 2010". Human Rights Watch. 2010.

- "A murder stirs Kurds in Syria". The Christian Science Monitor.

- Patrick Cockburn (18 April 2018). "Yazidis who suffered under Isis face forced conversion to Islam amid fresh persecution in Afrin". The Independent. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic: Twenty-seventh session". UN Human Rights Council.

- "Selected testimonies from victims of the Syrian conflict: Twenty-seventh session" (PDF). UN Human Rights Council.

- "Unviability of Islamic Caliphate: Ethnic Barriers - Part 1". Huffington Post. 7 January 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- Carr, Karen (3 August 2017). "The Reconquista - Medieval Spain". Quatr.us Study Guides. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "The Conquest of Granada". www.spanishwars.net. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "After 52-year ban, Syrian Kurds now taught Kurdish in schools". Al-Monitor. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "Stop aping Arabs, Johor Sultan tells Malays". Malay Mail Online. KUALA LUMPUR. 24 March 2016.

- "Stop trying to be like Arabs, Johor ruler tells Malays". The Straits Times. JOHOR BARU. 24 March 2016.

- "Johor Sultan Says Be Malay Not Arab". Asia Sentinel. 28 March 2016.

- Zainuddin, Abdul Mursyid (24 March 2016). "Berhenti Cuba Jadi 'Seperti Arab' – Sultan Johor". Suara TV. JOHOR BAHRU. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017.

- "Sultan Johor Ajak Malaysia Jaga Tradisi Melayu, Bukan Arab". TEMPO.CO. TEMPO.CO , Kuala Lumpu. 24 March 2016.

- wong, chun wai (24 March 2016). "Stop trying to be like Arabs, Ruler advises Malays". The Star Online. JOHOR BARU.

- "Stop aping Arabs, Johor Sultan tells Malays". TODAYonline. KUALA LUMPUR. 24 March 2016.

- "Arab culture integral to Islam, Johor sultan advised". malaysiakini. 24 March 2016.

- Irsyad, Arief (7 April 2016). "Is "Arabisation" A Threat To The Malay Identity As Claimed By The Johor Sultan? Here's What Some Malays Have To Say". Malaysian Digest.

References

- Attribution

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 103.

This article incorporates text from Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17, by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17, by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States. This article incorporates text from Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17, by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 17, by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, JSTOR (Organization), a publication from 1888, now in the public domain in the United States.