Agriculture in Mesoamerica

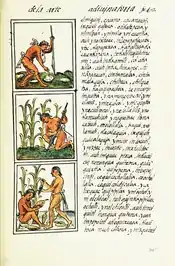

Agriculture in Mesoamerica dates to the Archaic period of Mesoamerican chronology (8000–2000 BC).[1] At the beginning of the Archaic period, the Early Hunters of the late Pleistocene era (50,000–10,000 BC) led nomadic lifestyles, relying on hunting and gathering for sustenance. However, the nomadic lifestyle that dominated the late Pleistocene and the early Archaic slowly transitioned into a more sedentary lifestyle as the hunter gatherer micro-bands in the region began to cultivate wild plants. The cultivation of these plants provided security to the Mesoamericans, allowing them to increase surplus of "starvation foods" near seasonal camps; this surplus could be utilized when hunting was bad, during times of drought, and when resources were low. The cultivation of plants could have been started purposefully, or by accident. The former could have been done by bringing a wild plant closer to a camp site, or to a frequented area, so it was easier access and collect. The latter could have happened as certain plant seeds were eaten and not fully digested, causing these plants to grow wherever human habitation would take them.

As the Archaic period progressed, cultivation of plant foods became increasingly important to the people of Mesoamerica. The reliability of cultivated plants allowed hunting and gathering micro-bands to establish permanent settlements and to increase in size. These larger settlements required a greater quantity of food, consequently leading to an even greater reliance on domesticated crops. Eventually, the Mesoamerican people established a sedentary lifestyle based on plant domestication and cultivation, supplemented with small game hunting. This sedentary lifestyle reliant on agriculture allowed permanent settlements to grow into villages and provided the opportunity for division of labor and social stratification.

The most important plant in ancient Mesoamerica, is, unarguably, maize. Squash and beans are also important staples of the ancient Mesoamerican agricultural diet and along with maize, are often referred to as the "Three Sisters".

Early and Culturally Significant Domesticated Plants

Richard S. MacNeish completed an extensive archaeological survey of Mesoamerica, during which he found the maize cobs in caves in Tehuacan, Puebla. It was originally suspected that these cobs date back to circa 5000 BC, however after radiocarbon dating it was determined that these finds date to 3500 BC.[1] The earliest dated maize cob was discovered in Guilá Naquitz cave in Oaxaca and dates back to 4300 BC.[1] Maize arrived at this point through the catastrophic sexual transmutation of Teosinte,[2] the ancestor of maize. It became the single most important crop in all of Mesoamerica. Maize is storable for long periods of time, it can be ground into flour, and it easily turns into surplus for future use. Maize became vital to the survival of the people of Mesoamerica; this is reflected in their origin myths, artwork, and rituals. The Maize God is depicted throughout Mesoamerica in stone figurines, carvings on altars, and even on temples, further signifying the importance of maize to the Mesoamerican peoples.

Another important crop in Mesoamerican agriculture is squash. Bruce D. Smith discovered evidence of domesticated squash (Cucurbita pepo), in Guilá Naquitz cave in Oaxaca.[1] These finds date back to 8000 BC, the beginning of the Archaic period, and are related to today's pumpkin. Another important squash that was domesticated in the early Archaic period was the bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria).[1] The bottle gourd provided storage space for collecting seeds for grinding or planting as well as a means of carrying water. Squashes provided an excellent source of protein to the ancient Mesoamericans, as well as to people today.

Another major food source in Mesoamerica are beans. Maize, beans, and squash form a triad of products, commonly referred to as the "Three Sisters". Growing these three crops together helps to retain nutrients in the soil.

Rubber trees and cotton plants were useful for making culturally significant products such as rubber balls for Mesoamerican ball games and textiles, respectively. Evidence of these ball games is found throughout Mesoamerica, and the performance of these games is related to many origin myths of the Mesoamerican people. The game had a ritualistic significance and was often accompanied with human sacrifice. The domestication of cotton allowed for textiles of vibrant colors to be created. These textiles are evidence of the Mesoamerican peoples' fascination with adornment and the cultural value they placed on appearance.

Another culturally important plant was cacao (ancient Mesoamerican chocolate). Cacao was used in rituals (as a drink) and was also used as currency in trade.

The crops above are only a few of the domesticated plants important to the ancient peoples of Mesoamerica. Please see the section below for a more comprehensive list of ancient Mesoamerican domesticated plants.

Domesticated Plants

Main source: Pre-Columbian Foodways A list of Mesoamerican cultivars and staples:

- Agave* - also known as the Century plant

- Anona – this fruit is also called the "Custard Apple"

- Avocado* - large, green, egg-shaped berry with a single seed

- Cacao* - the main ingredient in chocolate.

- Cassava* - edible starchy root also known as manioc; also used to make tapioca

- Chaya – large fast growing leafy shrub whose uses are similar to spinach

- Cherimoya* (fruit)

- Chicle* (Manilkara chicle) – sap made into chewing gum

- Chili peppers* - many varieties

- Copal – incense used by the Maya for religious practices [3]

- Cotton* - a shrub that is used mainly to create textiles

- Epazote (Dysphania ambrosioides) – aromatic herb

- Guayaba* - guava fruit

- Huautli* (Amaranthus cruentus, Amaranthus hypochondriacus) – grain

- Jícama* (Pachyrhizus erosus)

- Maize* - domesticated from teosinte grasses in southern Mexico)

- Mamey sapote* (Pouteria sapota) – fruit, other parts of plants have noted uses

- Mora (Rubus blackberry)

- Nopales* - stem segments of Opuntia species, such as Opuntia ficus-indica

- Papaya* (Carica papaya)

- Pineapple – cultivated extensively

- Pinto bean - "painted/speckled" bean; nitrogen-fixer traditionally planted in conjunction with the "two sisters", maize and squash, to help condition soil; runners grew on maize

- Potato* - a starch of the family Solanaceae

- Squash* (Cucurbita spp.) – pumpkins, zucchini, acorn squash, others

- Strawberry (Fragaria spp.) – various cultivars

- Sunflower seeds – under cultivation in Mexico and Peru for thousands of years, also source of essential oils

- Tobacco* - a dried leaf used as a trade commodity and peace-making.

- Tomato* - red berry-type fruit of the family Solanaceae

- Tunas* - fruits of Opuntia species, also called the prickly pear

- Vanilla – orchids grown for their culinary flavor

* Asterisk indicates a common English or Spanish word derived from an indigenous word

Farming Techniques

One of the greatest challenges in Mesoamerica for farmers is the lack of usable land, and the poor condition of the soil. The two main ways to combat poor soil quality, or lack of nutrients in the soil, are to leave fields fallow for a period of time in a milpa cycle, and to use slash-and-burn techniques.[3] In slash and burn agriculture, trees are cut down and left to dry for a period of time. The dry wood and grasses are then set on fire, and the resulting ash adds nutrients to the soil. These two techniques are often combined to retain as many nutrients as possible. However, in the jungle environment, no matter how careful a farmer is, nutrients are often hard to retain. To combat the lack of large tracts of usable land, farmers in Mesoamerica have found ways to create more land.

The first way to create land is to form terraces along the slopes of mountain valleys. Terraces allow farmers to use more land on the mountain slopes, and to move further up the mountain than they normally would be able to. Some terraces were made out of walls of stones, and others were created by cutting down large trees, and mounding soil around them. There is evidence that the Maya and the Aztecs used raised fields in some of the swampy areas, and onto the flood plains. However, the Aztecs also created floating plots of land called chinampas. These were plots of mud and soil, placed on top of layers of thick water vegetation. This farming style was imperative to the growth and survival of the city of Tenochtitlan, due to its location.[1]

Much of the Maya food supply was grown in gardens, known as pet kot.[4] The system takes its name from the low wall of stones (pet meaning circular and kot wall of loose stones) that characteristically surrounds the forest garden plot.[5] The earliest dated maize cobs was discovered in Guilá Naquitz cave in Oaxaca and dates back to 4300 BC. Maize arose through domestication of teosinte, which is considered to be the ancestor of maize. Maize can be stored for lengthy periods of time, it can be ground into flour, and it easily provides surplus for future use. Maize was vital to the survival of the Mesoamerican people. Its cultural significance is reflected in Mesoamerican origin myths, artwork, and rituals.

The Mesoamerican natives also used irrigation techniques not unlike other early agricultural societies in early Mesopotamia. However, unlike the arid plains of the Fertile Crescent, the Mesoamerican area has a rougher terrain, therefore making irrigation less effective than terraced farming and slash-and-burn techniques.[3]

Slash-and-burn techniques are a type of extensive farming, where the amount of labor is minimal in taking care of farmland. Extensive farming uses less labor but had a larger mark on the area around them. In opposition, intensive agriculture refers to agriculture that requires large amounts of labor however yields continuous results from the same land, thus making it better suited for a sedentary lifestyle.

See also

Notes

- Coe, Michael D.; Koontz, Rex (2013). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs (Seventh ed.). Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29076-7.

- Iltis, Hugh H. (25 November 1983). "From Teosinte to Maize: the Catastrophic Sexual Transmutation". Science. Lancaster, PA: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 222 (4626): 886–894. doi:10.1126/science.222.4626.886. PMID 17738466. S2CID 23247509.

- Coe, Michael D. (2011). The Maya (Eighth ed.). Thames &Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28902-0.

- Michael Ernest Smith; Marilyn A. Masson (2000). The Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-631-21116-7.

- David L. Lentz, ed. (2000). Imperfect Balance: Landscape Transformations in the Precolumbian Americas. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-231-11157-7.

References

- Atran, Scott; Lois, Ximena; Ucan Ek', Edilberto (2004). Plants of the Peten Itza Maya. Memoirs of the Museum of Anthropology, 38. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum.

- Schlesinger, Victoria (2001). Animals and Plants of the Ancient Maya: A Guide. Juan C. Chab-Medina (illus.), foreword by Carlos Galindo-Leal. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Piperno, Dolores R. (October 2011). "The Origins of Plant Cultivation and Domestication in the New World Tropics: Patterns, Process, and New Developments". Current Anthropology. 52: S453–S470. doi:10.1086/659998. JSTOR 10.1086/659998. S2CID 83061925.

- McLeay, P. (January 1980). "Review". Geography. 65: 75. JSTOR 40570293.

- Brown, Cecil H. (2010). Staller, John; Carrasco, Michael (eds.). Pre-Columbian Foodways. New York: Springer. pp. 71–100. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0471-3_3. ISBN 978-1-4419-0470-6.

- Coe, Michael D. (2011). The Maya (Eighth ed.). Thames &Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28902-0.

- Coe, Sophie D. (March 1994). America's First Cuisines (First ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71155-6.

- Harrington, S. P. M. 1997. Earliest Agriculture in the New World.

- Coe, Michael D.; Koontz, Rex (2013). From the Olmecs to the Aztecs (Seventh ed.). Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29076-7.

- Iltis, Hugh H. (25 November 1983). "From Teosinte to Maize: the Catastrophic Sexual Transmutation". Science. Lancaster, PA: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 222 (4626): 886–894. doi:10.1126/science.222.4626.886. PMID 17738466. S2CID 23247509.