Nitrogen fixation

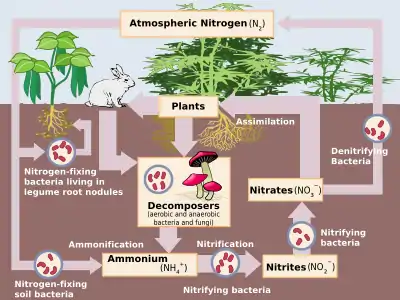

Nitrogen fixation is a process by which molecular nitrogen in the air is converted into ammonia (NH

3) or related nitrogenous compounds in soil.[1] Atmospheric nitrogen is molecular dinitrogen, a relatively nonreactive molecule that is metabolically useless to all but a few microorganisms. Biological nitrogen fixation converts N

2 into ammonia, which is metabolized by most organisms.

Nitrogen fixation is essential to life because fixed inorganic nitrogen compounds are required for the biosynthesis of all nitrogen-containing organic compounds, such as amino acids and proteins, nucleoside triphosphates and nucleic acids. As part of the nitrogen cycle, it is essential for agriculture and the manufacture of fertilizer. It is also, indirectly, relevant to the manufacture of all nitrogen chemical compounds, which includes some explosives, pharmaceuticals, and dyes.

Nitrogen fixation is carried out naturally in soil by microorganisms termed diazotrophs that include bacteria such as Azotobacter and archaea. Some nitrogen-fixing bacteria have symbiotic relationships with plant groups, especially legumes.[2] Looser non-symbiotic relationships between diazotrophs and plants are often referred to as associative, as seen in nitrogen fixation on rice roots. Nitrogen fixation occurs between some termites and fungi.[3] It occurs naturally in the air by means of NOx production by lightning.[4][5]

All biological reactions involving the process of nitrogen fixation are catalysed by enzymes called nitrogenases.[6] These enzymes contain iron, often with a second metal, usually molybdenum but sometimes vanadium.

Fixation

Non-biological

.jpg.webp)

2 starting the formation of nitrous acid.

Nitrogen can be fixed by lightning that converts nitrogen gas (N

2) and oxygen gas (O

2) present in the atmosphere into NO

x (nitrogen oxides). NO

x may react with water to make nitrous acid or nitric acid, which seeps into the soil, where it makes nitrate, which is of use to plants. Nitrogen in the atmosphere is highly stable and nonreactive due to the triple bond between atoms in the N

2 molecule.[7] Lightning produces enough energy and heat to break this bond[7] allowing nitrogen atoms to react with oxygen, forming NO

x. These compounds cannot be used by plants, but as this molecule cools, it reacts with oxygen to form NO

2.[8] This molecule in turn reacts with water to produce HNO

3 (nitric acid), or its ion NO−

3 (nitrate), which is usable by plants.[9][7]

Biological

Biological nitrogen fixation was discovered by Jean-Baptiste Boussingault in 1838.[10] Later, in 1880, the process by which it happens was discovered by German agronomist Hermann Hellriegel and Hermann Wilfarth[11] and was fully described by Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck.[12]

"The protracted investigations of the relation of plants to the acquisition of nitrogen begun by Saussure, Ville, Lawes and Gilbert and others culminated in the discover of symbiotic fixation by Hellriegel and Wilfarth in 1887."[13]

"Experiments by Bossingault in 1855 and Pugh, Gilbert & Lawes in 1887 had shown that nitrogen did not enter the plant directly. The discovery of the role of nitrogen fixing bacteria by Herman Hellriegel and Herman Wilfarth in 1886-8 would open a new era of soil science."[14]

In 1901 Beijerinck showed that azotobacter chroococcum was able to fix atmospheric nitrogen. This was the first species of the azotobacter genus, so-named by him. It is also the first known diazotroph, the species that use diatomic nitrogen as a step in the complete nitrogen cycle.

Biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) occurs when atmospheric nitrogen is converted to ammonia by a nitrogenase enzyme.[1] The overall reaction for BNF is:

The process is coupled to the hydrolysis of 16 equivalents of ATP and is accompanied by the co-formation of one equivalent of H

2.[15] The conversion of N

2 into ammonia occurs at a metal cluster called FeMoco, an abbreviation for the iron-molybdenum cofactor. The mechanism proceeds via a series of protonation and reduction steps wherein the FeMoco active site hydrogenates the N

2 substrate.[16] In free-living diazotrophs, nitrogenase-generated ammonia is assimilated into glutamate through the glutamine synthetase/glutamate synthase pathway. The microbial nif genes required for nitrogen fixation are widely distributed in diverse environments.[17]

For example decomposing wood which has generally low content of nitrogen was shown to host diazotrophic community.[18][19] Bacteria through fixation enrich wood substrate with nitrogen thus enabling deadwood decomposition by fungi.[20]

Nitrogenases are rapidly degraded by oxygen. For this reason, many bacteria cease production of the enzyme in the presence of oxygen. Many nitrogen-fixing organisms exist only in anaerobic conditions, respiring to draw down oxygen levels, or binding the oxygen with a protein such as leghemoglobin.[1]

Microorganisms

Diazotrophs are widespread within domain Bacteria including cyanobacteria (e.g. the highly significant Trichodesmium and Cyanothece), as well as green sulfur bacteria, Azotobacteraceae, rhizobia and Frankia. Several obligately anaerobic bacteria fix nitrogen including many (but not all) Clostridium spp. Some archaea also fix nitrogen, including several methanogenic taxa, which are significant contributors to nitrogen fixation in oxygen-deficient soils.[21]

Cyanobacteria inhabit nearly all illuminated environments on Earth and play key roles in the carbon and nitrogen cycle of the biosphere. In general, cyanobacteria can use various inorganic and organic sources of combined nitrogen, such as nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, urea, or some amino acids. Several cyanobacteria strains are also capable of diazotrophic growth, an ability that may have been present in their last common ancestor in the Archean eon.[22] Nitrogen fixation by cyanobacteria in coral reefs can fix twice as much nitrogen as on land—around 660 kg/ha/year. The colonial marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium is thought to fix nitrogen on such a scale that it accounts for almost half of the nitrogen fixation in marine systems globally.[23]

Marine surface lichens and non-photosynthetic bacteria belonging in Proteobacteria and Planctomycetes fixate significant atmospheric nitrogen.[24]

Root nodule symbioses

Legume family

Plants that contribute to nitrogen fixation include those of the legume family—Fabaceae— with taxa such as kudzu, clover, soybean, alfalfa, lupin, peanut and rooibos. They contain symbiotic rhizobia bacteria within nodules in their root systems, producing nitrogen compounds that help the plant to grow and compete with other plants.[25] When the plant dies, the fixed nitrogen is released, making it available to other plants; this helps to fertilize the soil.[1][26] The great majority of legumes have this association, but a few genera (e.g., Styphnolobium) do not. In many traditional farming practices, fields are rotated through various types of crops, which usually include one consisting mainly or entirely of clover.

Fixation efficiency in soil is dependent on many factors, including the legume and air and soil conditions. For example, nitrogen fixation by red clover can range from 50 to 200 lb./acre.[27]

Non-leguminous

Other nitrogen fixing families include:

- Parasponia, a tropical genus in the family Cannabaceae, which are able to interact with rhizobia and form nitrogen-fixing nodules[28]

- Actinorhizal plants such as alder and bayberry can form nitrogen-fixing nodules, thanks to a symbiotic association with Frankia bacteria. These plants belong to 25 genera[29] distributed across eight families.

The ability to fix nitrogen is present in other families that belong to the orders Cucurbitales, Fagales and Rosales, which together with the Fabales form a clade of eurosids. The ability to fix nitrogen is not universally present in these families. For example, of 122 Rosaceae genera, only four fix nitrogen. Fabales were the first lineage to branch off this nitrogen-fixing clade; thus, the ability to fix nitrogen may be plesiomorphic and subsequently lost in most descendants of the original nitrogen-fixing plant; however, it may be that the basic genetic and physiological requirements were present in an incipient state in the most recent common ancestors of all these plants, but only evolved to full function in some of them.

| Family: Genera

Betulaceae: Alnus (alders) |

|

|

Several nitrogen-fixing symbiotic associations involve cyanobacteria (such as Nostoc):

Endosymbiosis in diatoms

Rhopalodia gibba, a diatom alga, is a eukaryote with cyanobacterial N

2-fixing endosymbiont organelles. The spheroid bodies reside in the cytoplasm of the diatoms and are inseparable from their hosts.[31][32]

Eukaryotic Nitrogenase Engineering

Some scientists are working towards introducing the genes responsible for nitrogen fixation directly into plant DNA. As all known examples of nitrogen fixation takes place in prokaryotes, transferring the functionality to eukaryotes such as plant is a challenge; one team is using yeast as their eukaryotic test organism. A major problem to overcome is the oxygen-sensitivity of the produced enzymes, as well as the energy requirements. Having the process taking place inside of mitocondria or chloroplasts is being considered.[33]

Industrial processes

The possibility that atmospheric nitrogen reacts with certain chemicals was first observed by Desfosses in 1828. He observed that mixtures of alkali metal oxides and carbon react at high temperatures with nitrogen. With the use of barium carbonate as starting material, the first commercial process became available in the 1860s, developed by Margueritte and Sourdeval. The resulting barium cyanide could be reacted with steam yielding ammonia.

History

Prior to 1900, Tesla experimented with industrial nitrogen fixation "by using currents of extremely high frequency or rate of vibration".[34][35]

Frank-Caro process

In 1898 Frank and Caro decoupled the process and produced calcium carbide and in a subsequent step reacted it with nitrogen to calcium cyanamide. The Ostwald process for the production of nitric acid was discovered in 1902. The Frank-Caro and Ostwald processes dominated industrial fixation until the discovery of the Haber process in 1909.[36][37]

Haber process

The most common ammonia production method is the Haber process. Fertilizer production is now the largest source of human-produced fixed nitrogen in the terrestrial ecosystem. Ammonia is a required precursor to fertilizers, explosives, and other products. The Haber process requires high pressures (around 200 atm) and high temperatures (at least 400 °C), which are routine conditions for industrial catalysis. This process uses natural gas as a hydrogen source and air as a nitrogen source.[38]

Much research has been conducted on the discovery of catalysts for nitrogen fixation, often with the goal of reducing energy requirements. However, such research has thus far failed to approach the efficiency and ease of the Haber process. Many compounds react with atmospheric nitrogen to give dinitrogen complexes. The first dinitrogen complex to be reported was Ru(NH

3)

5(N

2)2+.[39]

Ambient nitrogen reduction

Achieving catalytic chemical nitrogen fixation at ambient conditions is an ongoing scientific endeavor. Guided by the example of nitrogenase, this area of homogeneous catalysis is ongoing, with particular emphasis on hydrogenation.[40]

Metallic lithium burns in an atmosphere of nitrogen and then converts to lithium nitride. Hydrolysis of the resulting nitride gives ammonia. In a related process, trimethylsilyl chloride, lithium and nitrogen react in the presence of a catalyst to give tris(trimethylsilyl)amine. This can then be used for reaction with α,δ,ω-triketones to give tricyclic pyrroles.[41] Processes involving lithium metal are however of no practical interest since they are non-catalytic and re-reducing the Li+

ion residue is difficult.

Beginning in the 1960s several homogeneous systems were identified that convert nitrogen to ammonia, sometimes catalytically, but often operating via ill-defined mechanisms. The original discovery is described in an early review:

"Vol'pin and co-workers, using a non-protic Lewis acid, aluminium tribromide, were able to demonstrate the truly catalytic effect of titanium by treating dinitrogen with a mixture of titanium tetrachloride, metallic aluminium, and aluminium tribromide at 50 °C, either in the absence or in the presence of a solvent, e.g. benzene. As much as 200 mol of ammonia per mol of TiCl

4 was obtained after hydrolysis.…"[42]

The quest for well-defined intermediates led to the characterization of many transition metal dinitrogen complexes. While few of these well-defined complexes function catalytically, their behavior illuminated likely stages in nitrogen fixation. Fruitful early studies focused on (MN20−

2)(dppe)2 (M = Mo, W), which protonates to give intermediates with ligand M=N−N

2. In 1995, a molybdenum(III) amido complex was discovered that cleaved N

2 to give the corresponding molybdenum (VI) nitride.[44] This and related terminal nitrido complexes have been used to make nitriles.[45]

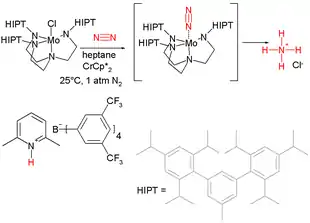

In 2003 a molybdenum amido complex was found to catalyze the reduction of N

2, albeit with few turnovers.[43][46][47][48] In these systems, like the biological one, hydrogen is provided to the substrate heterolytically, by means of protons and a strong reducing agent rather than with H

2.

In 2011, another molybdenum-based system was discovered, but with a diphosphorus pincer ligand.[49] Photolytic nitrogen splitting is also considered.[50][51][52][53][54]

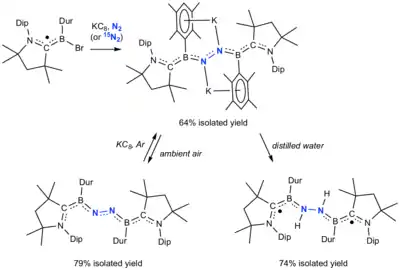

Nitrogen fixation at a p-block element was published in 2018 whereby one molecule of dinitrogen is bound by two transient Lewis-base-stabilized borylene species.[55] The resulting dianion was subsequently oxidized to a neutral compound, and reduced using water.

Photochemical and electrochemical nitrogen reduction

With the help of catalysis and energy provided by electricity and light, NH

3 can be produced directly from nitrogen and water at ambient temperature and pressure.

Research

As of 2019 research was considering alternate means of supplying nitrogen in agriculture. Instead of using fertilizer, researchers were considering using different species of bacteria and separately, coating seeds with probiotics that encourage the growth of nitrogen-fixing bacteria.[56]

See also

- Birkeland–Eyde process: an industrial fertiliser production process

- George Washington Carver: an American botanist

- Denitrification: an organic process of nitrogen release

- Heterocyst

- Nitrification: biological production of nitrogen

- Nitrogen cycle: the flow and transformation of nitrogen through the environment

- Nitrogen deficiency

- Nitrogen fixation package for quantitative measurement of nitrogen fixation by plants

- Nitrogenase: enzymes used by organisms to fix nitrogen

- Ostwald process: a chemical process for making nitric acid (HNO

3) - Push–pull technology: the use of both repellent and attractive organisms in agriculture

References

- Postgate, J. (1998). Nitrogen Fixation (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zahran, HH (December 1999). "Rhizobium-legume symbiosis and nitrogen fixation under severe conditions and in an arid climate". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 63 (4): 968–89, table of contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.63.4.968-989.1999. PMC 98982. PMID 10585971.

- Sapountzis, P (2016). "Potential for Nitrogen Fixation in the Fungus-Growing Termite Symbiosis". Frontiers in Microbiology. 7: 1993. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01993. PMC 5156715. PMID 28018322.

- Slosson, Edwin (1919). Creative Chemistry. New York, NY: The Century Co. pp. 19–37.

- Hill, R. D.; Rinker, R. G.; Wilson, H. Dale (1979). "Atmospheric Nitrogen Fixation by Lightning". J. Atmos. Sci. 37 (1): 179–192. Bibcode:1980JAtS...37..179H. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1980)037<0179:ANFBL>2.0.CO;2.

- Wagner SC (2011). "Biological Nitrogen Fixation". Nature Education Knowledge. 3 (10): 15. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- Tuck, A. F. (October 1976). "Production of nitrogen oxides by lightning discharges". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 102 (434): 749–755. Bibcode:1976QJRMS.102..749T. doi:10.1002/qj.49710243404. ISSN 0035-9009.

- Hill, R.D. (August 1979). "Atmospheric Nitrogen Fixation by Lightning". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 37: 179–192. Bibcode:1980JAtS...37..179H. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1980)037<0179:ANFBL>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0469.

- LEVIN, JOEL S (1984). "Tropospheric Sources of NOx: Lightning And Biology". Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- Smil, V. (2001). Enriching the Earth. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Hellriegel, H.; Wilfarth, H. (1888). Untersuchungen über die Stickstoffnahrung der Gramineen und Leguminosen [Studies on the nitrogen intake of Gramineae and Leguminosae]. Berlin: Buchdruckerei der "Post" Kayssler & Co.

- Beijerinck, M. W. (1901). "Über oligonitrophile Mikroben" [On oligonitrophilic microbes]. Centralblatt für Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde, Infektionskrankheiten und Hygiene. 7 (2): 561–582.

- Howard S. Reed (1942) A Short History of Plant Science, page 230, Chronic Publishing

- Margaret Rossiter (1975) The Emergence of Agricultural Science, page 146, Yale University Press

- Chi Chung, Lee; Markus W., Ribbe; Yilin, Hu (2014). "Chapter 7. Cleaving the N,N Triple Bond: The Transformation of Dinitrogen to Ammonia by Nitrogenases". In Kroneck, Peter M. H.; Sosa Torres, Martha E. (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 14. Springer. pp. 147–174. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_7. PMID 25416394.

- Hoffman, B. M.; Lukoyanov, D.; Dean, D. R.; Seefeldt, L. C. (2013). "Nitrogenase: A Draft Mechanism". Acc. Chem. Res. 46 (2): 587–595. doi:10.1021/ar300267m. PMC 3578145. PMID 23289741.

- Gaby, J. C.; Buckley, D. H. (2011). "A global census of nitrogenase diversity". Environ. Microbiol. 13 (7): 1790–1799. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02488.x. PMID 21535343.

- Rinne, Katja T.; Rajala, Tiina; Peltoniemi, Krista; Chen, Janet; Smolander, Aino; Mäkipää, Raisa (2017). "Accumulation rates and sources of external nitrogen in decaying wood in a Norway spruce dominated forest". Functional Ecology. 31 (2): 530–541. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12734. ISSN 1365-2435.

- Hoppe, B.; Kahl, T.; Karasch, P.; Wubet, T.; Bauhus, J.; Buscot, F.; Krüger, D. (2014). "Network analysis reveals ecological links between N-fixing bacteria and wood-decaying fungi". PLOS ONE. 9 (2): e88141. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...988141H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088141. PMC 3914916. PMID 24505405.

- Tláskal, Vojtěch; Brabcová, Vendula; Větrovský, Tomáš; Jomura, Mayuko; López-Mondéjar, Rubén; Monteiro, Lummy Maria Oliveira; Saraiva, João Pedro; Human, Zander Rainier; Cajthaml, Tomáš; Rocha, Ulisses Nunes da; Baldrian, Petr (23 February 2021). "Complementary Roles of Wood-Inhabiting Fungi and Bacteria Facilitate Deadwood Decomposition". mSystems. 6 (1). doi:10.1128/mSystems.01078-20. ISSN 2379-5077. PMID 33436515.

- Bae, Hee-Sung; Morrison, Elise; Chanton, Jeffrey P.; Ogram, Andrew (1 April 2018). "Methanogens Are Major Contributors to Nitrogen Fixation in Soils of the Florida Everglades". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 84 (7): e02222–17. doi:10.1128/AEM.02222-17. PMC 5861825. PMID 29374038.

- Latysheva, N.; Junker, V. L.; Palmer, W. J.; Codd, G. A.; Barker, D. (2012). "The evolution of nitrogen fixation in cyanobacteria". Bioinformatics. 28 (5): 603–606. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts008. PMID 22238262.

- Bergman, B.; Sandh, G.; Lin, S.; Larsson, H.; Carpenter, E. J. (2012). "Trichodesmium – a widespread marine cyanobacterium with unusual nitrogen fixation properties". FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37 (3): 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00352.x. PMC 3655545. PMID 22928644.

- "Large-scale study indicates novel, abundant nitrogen-fixing microbes in surface ocean". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Kuypers, MMM; Marchant, HK; Kartal, B (2011). "The Microbial Nitrogen-Cycling Network". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 1 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2018.9. PMID 29398704. S2CID 3948918.

- Smil, Vaclav (2000). Cycles of Life. Scientific American Library.

- "Nitrogen Fixation and Inoculation of Forage Legumes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2016.

- Op den Camp, Rik; Streng, A.; De Mita, S.; Cao, Q.; Polone, E.; Liu, W.; Ammiraju, J. S. S.; Kudrna, D.; Wing, R.; Untergasser, A.; Bisseling, T.; Geurts, R. (2010). "LysM-Type Mycorrhizal Receptor Recruited for Rhizobium Symbiosis in Nonlegume Parasponia". Science. 331 (6019): 909–912. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..909O. doi:10.1126/science.1198181. PMID 21205637. S2CID 20501765.

- Dawson, J. O. (2008). "Ecology of actinorhizal plants". Nitrogen-fixing Actinorhizal Symbioses. Nitrogen Fixation: Origins, Applications, and Research Progress. 6. Springer. pp. 199–234. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-3547-0_8. ISBN 978-1-4020-3540-1.

- Rai, A. N. (2000). "Cyanobacterium-plant symbioses". New Phytologist. 147: 449–481. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00720.x.

- Prechtl, Julia; Kneip, Christoph; Lockhart, Peter; Wenderoth, Klaus; Maier, Uwe-G. (2004). "Intracellular spheroid bodies of Rhopalodia gibba have nitrogen-fixing apparatus of cyanobacterial origin". Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 (8): 1477–81. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh086. PMID 14963089.

- Nakayama, Takuro; Inagaki, Yuji (2014). "Unique genome evolution in an intracellular N

2-fixing symbiont of a rhopalodiacean diatom". Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 83 (4): 409–413. doi:10.5586/asbp.2014.046. - Stefan Burén and Luis M. R (2018), "State of the Art in Eukaryotic Nitrogenase Engineering", FEMS Microbiology Letters, 365 (2), doi:10.1093/femsle/fnx274, PMC 5812491, PMID 29240940, archived from the original on 2 June 2018, retrieved 26 November 2019CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ""The Problem of Increasing Human Energy" by Nikola Tesla". Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Tesla, Nikola (1900). "The Problem of Increasing Human Energy". The Century Magazine. 60 (n.s. v. 38) (1900 May–Oct): 175. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- Heinrich, H.; Nevbner, Rolf (1934). "Die Umwandlungsgleichung Ba(CN)

2 → BaCN

2 + C im Temperaturgebiet von 500 bis 1000 °C" [The conversion reaction Ba(CN)

2 → BaCN

2 + C in the temperature range from 500 to 1,000 °C]. Z. Elektrochem. Angew. Phys. Chem. 40 (10): 693–698. doi:10.1002/bbpc.19340401005 (inactive 17 January 2021). Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link) - Curtis, Harry Alfred (1932). Fixed nitrogen.

- Vitousek, Peter M.; Aber, John; Howarth, Robert W.; Likens, Gene E.; Matson, Pamela A.; Schindler, David W.; Schlesinger, William H.; Tilman, G. David. "Human Alteration of the Global Nitrogen Cycle: Causes and Consequences" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- Allen, A. D.; Senoff, C. V. (1965). "Nitrogenopentammineruthenium(II) complexes". J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. (24): 621. doi:10.1039/C19650000621.

- Schrock, Richard R. (2006). "Reduction of dinitrogen" (PDF). PNAS. 103 (46): 17087. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317087S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603633103. PMC 1859893. PMID 17088548. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Brook, Michael A. (2000). Silicon in Organic, Organometallic, and Polymer Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 193–194.

- Chatt, J.; Leigh, G. J. (1972). "Nitrogen Fixation". Chem. Soc. Rev. 1: 121. doi:10.1039/cs9720100121.

- Yandulov, Dmitry V.; Schrock, Richard R.; Rheingold, Arnold L.; Ceccarelli, Christopher; Davis, William M. (2003). "Synthesis and Reactions of Molybdenum Triamidoamine Complexes Containing Hexaisopropylterphenyl Substituents". Inorg. Chem. 42 (3): 796–813. doi:10.1021/ic020505l. PMID 12562193.

- Laplaza, Catalina E.; Cummins, Christopher C. (1995). "Dinitrogen Cleavage by a Three-Coordinate Molybdenum(III) Complex". Science. 268 (5212): 861–863. Bibcode:1995Sci...268..861L. doi:10.1126/science.268.5212.861. PMID 17792182. S2CID 28465423.

- Curley, John J.; Sceats, Emma L.; Cummins, Christopher C. (2006). "A Cycle for Organic Nitrile Synthesis via Dinitrogen Cleavage". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (43): 14036–14037. doi:10.1021/ja066090a. PMID 17061880.

- Yandulov, Dmitry V.; Schrock, Richard R. (2003). "Catalytic Reduction of Dinitrogen to Ammonia at a Single Molybdenum Center". Science. 301 (5629): 76–78. Bibcode:2003Sci...301...76Y. doi:10.1126/science.1085326. PMID 12843387. S2CID 29046992.

- The catalyst is derived from molybdenum(V) chloride and tris(2-aminoethyl)amine N-substituted with three bulky hexa-isopropylterphenyl (HIPT) groups. Nitrogen adds end-on to the molybdenum atom, and the bulky HIPT substituents prevent the formation of the stable and nonreactive Mo−N=N−Mo dimer. In this isolated pocket is the Mo−N

2. The proton donor is a pyridinium salt of weakly coordinating counter anion. The reducing agent is decamethylchromocene. All ammonia formed is collected as the HCl salt by trapping the distillate with a HCl solution. - Although the dinitrogen complex is shown in brackets, this species can be isolated and characterized. The brackets do not indicate that the intermediate is not observed.

- Arashiba, Kazuya; Miyake, Yoshihiro; Nishibayashi, Yoshiaki (2011). "A molybdenum complex bearing PNP-type pincer ligands leads to the catalytic reduction of dinitrogen into ammonia". Nature Chemistry. 3 (2): 120–125. Bibcode:2011NatCh...3..120A. doi:10.1038/nchem.906. PMID 21258384.

- Rebreyend, C.; de Bruin, B. (2014). "Photolytic N

2 Splitting: A Road to Sustainable NH

3 Production?". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (1): 42–44. doi:10.1002/anie.201409727. PMID 25382116. - Solari, E.; Da Silva, C.; Iacono, B.; Hesschenbrouck, J.; Rizzoli, C.; Scopelliti, R.; Floriani, C. (2001). "Photochemical Activation of the N≡N Bond in a Dimolybdenum–Dinitrogen Complex: Formation of a Molybdenum Nitride". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 40 (20): 3907–3909. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20011015)40:20<3907::AID-ANIE3907>3.0.CO;2-#. PMID 29712125.

- Huss, Adam S.; Curley, John J.; Cummins, Christopher C.; Blank, David A. (2013). "Relaxation and Dissociation Following Photoexcitation of the (μ-N

2)[Mo(N[t-Bu]Ar)3]2 Dinitrogen Cleavage Intermediate". J. Phys. Chem. B. 117 (5): 1429–1436. doi:10.1021/jp310122x. PMID 23249096. - Kunkely, H.; Vogler, A. (2010). "Photolysis of Aqueous [(NH

3)5Os(μ-N

2)Os(NH

3)5]5+: Cleavage of Dinitrogen by an Intramolecular Photoredox Reaction". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (9): 1591–1593. doi:10.1002/anie.200905026. PMID 20135653. - Miyazaki, T.; Tanaka, H.; Tanabe, Y.; Yuki, M.; Nakajima, K.; Yoshizawa, K.; Nishibayashi, Y. (2014). "Cleavage and Formation of Molecular Dinitrogen in a Single System Assisted by Molybdenum Complexes Bearing Ferrocenyldiphosphine". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (43): 11488–11492. doi:10.1002/anie.201405673. PMID 25214300.

- Broere, Daniël L. J.; Holland, Patrick L. (23 February 2018). "Boron compounds tackle dinitrogen". Science. 359 (6378): 871. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..871B. doi:10.1126/science.aar7395. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 6101238. PMID 29472470.

- Grist (3 October 2018). "Billionaires and Bacteria Are Racing to Save Us From Death by Fertilizer". Medium. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

External links

- Hirsch, Ann M. (2009). "A Brief History of the Discovery of Nitrogen-fixing Organisms" (PDF). University of California, Los Angeles.

- "Marine Nitrogen Fixation laboratory". University of Southern California.

- "Travis P. Hignett Collection of Fixed Nitrogen Research Laboratory Photographs // Science History Institute Digital Collections". digital.sciencehistory.org. Retrieved 16 August 2019. Science History Institute Digital Collections (Photographs depicting numerous stages of the nitrogen fixation process and the various equipment and apparatus used in the production of atmospheric nitrogen, including generators, compressors, filters, thermostats, and vacuum and blast furnaces).