Aircraft of the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain (German: Luftschlacht um England) was an effort by the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) during the summer and autumn of 1940 to gain air superiority over the Royal Air Force (RAF) of the United Kingdom in preparation for the planned amphibious and airborne forces invasion of Britain by Operation Sea Lion. Neither the German leader Adolf Hitler nor his High Command of the Armed Forces (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, or OKW) believed it was possible to carry out a successful amphibious assault on Britain until the RAF had been neutralised. Secondary objectives were to destroy aircraft production and ground infrastructure, to attack areas of political significance, and to terrorise the British people into seeking an armistice or surrender.

| Aircraft of the Battle of Britain | |

|---|---|

| |

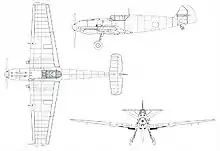

| R4118 flew 49 sorties while on 605 Squadron during the Battle of Britain, and is currently the only Battle of Britain Hurricane still flying.[1] |

The British date the battle from 10 July to 31 October 1940, which represented the most intense period of daylight bombing. German historians usually place the beginning of the battle in mid-August 1940 and end it in May 1941, on the withdrawal of the German bomber units in preparation for Operation Barbarossa, the campaign against the Soviet Union.

The Battle of Britain was the first major campaign to be fought entirely by air forces; the British in the defensive were mainly using fighter aircraft, the Germans used a mixture of bombers with fighter protection. It was the largest and most sustained bombing campaign attempted up until that date. The failure of Nazi Germany to destroy Britain's air defence or to break British morale is considered its first major setback.[2]

Fighter aircraft

Main types: Hurricane, Spitfire and Bf 109

The most famous fighter aircraft used in the Battle of Britain were the British Hawker Hurricane and Supermarine Spitfire Mk I and the German Messerschmitt Bf 109 E variant (Emil) single-engined fighters. Although the Spitfire has attracted more attention,[3] the Hurricanes were more numerous and were responsible for most of the German losses, especially in the early part of the battle. The turn-around time (re-arm and refuel) for the Spitfire was 26 minutes, while the Hurricane's was 9 minutes, which increased its effectiveness.

Many of the Spitfires used in the battle were purchased privately. Money raised by towns, companies, clubs or individuals was used to buy Spitfires for £5,000 each with the purchaser having naming rights. Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands donated £215,000 to purchase 43 Spitfires.

The Spitfire and Bf 109E were well-matched in speed and agility, and both were somewhat faster than the Hurricane.[4] The slightly larger Hurricane was regarded as an easier aircraft to fly and was effective against Luftwaffe bombers.[5] The Royal Air Force's preferred tactic was to deploy the Hurricanes against formations of bombers and to use the Spitfires against the fighter escorts. The view from the "blown" clear cockpit hood of the Spitfire was considered fair, while upwards good; view to the rear was considered fair for a covered cockpit. The curved plexiglass windscreen however was very bad optically and caused considerable distortion, which made long-distance visual scanning difficult. Spitfire pilot Jeffrey Quill made recommendations for the installation of "optically true" glass into the side panels to solve the problem.[6] The Hurricane had a higher seating position, which gave the pilot a better view over the nose than the Spitfire. The upper canopy panels of the Bf 109 through its E-3 subtype were curved, while the E-4 and later Emil subtypes were modified for better visibility with flat panels and the new design was often retrofitted to earlier 109s.

Handling and general overview

Each of the three main fighters had advantages and disadvantages in their control characteristics; much of the air combat during the battle occurred at about 20,000 feet or lower. Due to its sensitive elevators, if the stick was pulled back too far on the Spitfire in a tight turn:

stalling incidence may be reached and a high speed stall induced. When this occurs, there is a violent shudder and clattering noise throughout the aeroplane which tends to flick over laterally and, unless the control column is put forward instantly a rapid roll and spin will result.[7]

During tight turns the "twist" or washout designed into the wing by Reginald Mitchell meant that the wing root would stall before the wingtips, creating the shuddering and clattering referred to. This noise was a form of stall warning, reminding the pilot to ease up on the turn.[8] British testing in September 1940 revealed that some Bf 109 pilots succeeded in keeping on the tail of the Spitfire, despite the latter aircraft's superior turning performance, because a number of the Spitfire pilots failed to tighten up the turn sufficiently.[9] The gentle stall and good control under "g" of the Bf 109 were of some importance, as they enabled the Luftwaffe' pilot to get the most out of the aircraft in a circling dog-fight by flying very near the stall. The Bf 109 used leading edge slats which automatically deployed prior to stalling, but also made it much more difficult to continue chasing either a Hurricane or Spitfire with a tight turn in aerial combat manoeuvres, from the slats intermittently opening in tight turns (on the wing to the "inside" of a turn) during dogfights, even causing problems during a takeoff if they opened unevenly.[10]

The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine of the British fighters had the drawback of being equipped with a float-type carburettor which cut out under negative "g" forces. The direct-fuel injected Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine gave the 109 an advantage over the carburettor-equipped engine; when an RAF fighter attempted to "bunt" (the diving entry into an outside loop) and dive away from an opponent as the 109 could, their engines would temporarily cut out for the duration of the negative-g forces. This ability to perform negative-g manoeuvres without the engine cutting out gave a 109 pilot better ability to disengage at will.[11]

On the question of comparative turning circles in combat, Spitfires and Hurricanes benefited from their lower wing loading compared with the Bf 109: the Royal Aircraft Establishment estimated the Spitfire's turning circle – without height loss – as 212 m (700 ft) in radius (the Hurricane's would be slightly tighter) while the 109E's was estimated as 270 m (890 ft) radius at 3,657 m (12,000 ft).[9] Other sources variously list a turn radius of between 125 m (410 ft) and 170 m (558 ft)at ground level and 230 m (754 ft) at 6,000 m (19,690 ft) for the 109E.[12][13] The Emil was smaller than either RAF fighter, and it was more difficult to land and take off than the Spitfire and Hurricane.[14] At high speeds controls tightened considerably, and the Bf 109E needed more strength to manoeuvre than either of its main opponents. Of all three fighters, the Bf 109E would possess the highest roll rate, with the aileron controls being brisk and responsive; the Spitfire had the highest aileron forces, but both the Spitfire and the Messerschmitt's rate of roll suffered at high speed.

Overall the differences in performance between the Bf 109 and Spitfire were marginal and in combat they were surmounted by tactical considerations such as which side had seen the other first, which side had the advantage of altitude, numbers, pilot ability etc. with the main difference between the two aircraft being the Spitfire's tighter turning ability and the Bf 109's faster climb rate.[4]

Armament

Both RAF fighters were armed with eight .303 Browning machine guns in the wings, harmonised by the squadrons to allow the bullets to converge at a distance. The Brownings had a high rate of fire and even a short burst from the eight machine guns sent out a large number of bullets. Although efficient against many aircraft, the small calibre bullets were often unable to penetrate the armour plating which was being increasingly used in Luftwaffe aircraft to protect crew and vital areas. An incendiary round, called the "De Wilde" was available, and this could do more damage than the standard "ball" rounds.[15]

During the battle at least one Hurricane was experimentally armed with a single Hispano 20 mm cannon in a pod under each wing although it proved to be too slow and sluggish on the controls to be effective.[16] Several Spitfires, designated Spitfire Mk. IBs, were also modified to carry a Hispano cannon in each wing panel. 19 Squadron was equipped with this version in June 1940. On entering combat in August this first cannon armed Spitfire failed to create an impact, with the guns often jamming and unable to fire. When it did work, however, the Hispano was an effective weapon, with its shells easily able to penetrate the armour plating and self-sealing fuel tanks of Luftwaffe aircraft.[17]

The Emil's main armament depended on the subtype. The E-1 was armed with four MG 17 7.92mm machine guns; two cowl guns above the engine with 1,000 rounds per gun, and two in the wings with 500 rounds per gun. The E-3, E-4 and E-7s retained the fuselage armament of the E-1 but replaced the MG 17 wing guns with two 20 mm cannons, one in each wing with 60 rpg; either MG FFs (E-3) or the more advanced MG FF/M (E-4 and E-7) that could fire the new German steel-cartridge Minengeschoß mine shell ammunition. Although the explosive shells had greater destructive power than the bullets of the Brownings, these cannon's low muzzle velocity and the limited ammunition capacity of their sixty-round drum magazines meant that the armament was not markedly superior to the RAF fighter's eight machine guns.

Three or four hits from the cannons were usually enough to bring down an enemy fighter and, even if the fighter was able to return to base, it would often be written off.[18] For example, on 18 August a brand new Spitfire of 602 Squadron was hit by 20 mm shells which exploded in the structure of the rear fuselage. Although the crippled aircraft was successfully landed back at its airfield it was subsequently deemed to be unrepairable.[19]

The MG FF/M, used in the Bf 109E-4, was modified to fire the more destructive, high-capacity mine-shells propelling the lighter shells at greater velocities than the MG FF.[20][21] The early shells of this type had contact fusing, detonating on contact with the skin of the airframe rather than penetrating, then exploding.[22] The more streamlined Bf 109 F-1, issued in small numbers starting in October, carried two cowl MG-17s and a single 20mm MG FF/M in the fuselage as an engine-mounted Motorkanone, firing through the propeller hub.

Fuel tanks

A drawback of the Hurricane was the presence of a fuel tank just behind the engine firewall, which could catch fire and within a few seconds severely burn the pilot before he managed to bail out. This was later partly solved by fitting a layer of "Linatex" fire-resistant material to the tank, and an armoured panel forward of the instrument panel. Another hazard was presented by the main wing root mounted fuel tanks of the Hurricane, which were vulnerable to bullets fired from behind.[23] The main fuel tanks of the Spitfire, which were mounted in the fuselage forward of the cockpit, were better protected than that of the Hurricane; the lower tank was self-sealing and a panel of 3 mm thick aluminium, sufficient to deflect small calibre bullets, was wrapped externally over the top tanks. Internally they were coated with layers of "Linatex" and the cockpit bulkhead was fireproofed with a thick panel of asbestos.[23][24] On all the German fighters and bombers, the fuel tanks were self-sealing, and although capable of sealing leaks from enemy rounds, this could not prevent possibly fatal damage being inflicted by the "De Wilde" incendiary round which was being used by the RAF.

German fighter fuel capacity

A much more serious issue for the Luftwaffe's single-engined fighter force during the Battle was the Bf 109E's limited fuel capacity as originally designed. The Bf 109E escorts had a limited fuel capacity resulting in only a 660 km (410 mile) maximum range solely on internal fuel,[25] and when they arrived over a British target, had only 10 minutes of flying time before turning for home, leaving the bombers undefended by fighter escorts. Its eventual stablemate, the Focke-Wulf Fw 190A, was only flying in prototype form in the summer of 1940; the first 28 Fw 190A-0 service test examples were not delivered until November 1940. The Fw 190A-1 had a maximum range of 940 km (584 miles) on internal fuel, 40% greater than the Bf 109E.[26] The Messerschmitt Bf 109E-7 corrected this deficiency by adding a ventral center-line ordnance rack to take either an SC 250 bomb for Jabo duties, or a standard 300 litre (66 Imp. gal/80 US gallon) capacity Luftwaffe drop tank to double the range to 1,325 km (820 mi). The ordnance rack was not retrofitted to earlier Bf 109Es until October 1940.

Durability and armour

The Spitfire, from about mid-1940, had 73 pounds (33 kg) of armoured steel plating in the form of head (of 6.5 mm thickness) and back protection on the seat bulkhead (4.5 mm), and covering the forward face of the glycol header tank.[24] The Hurricane had a similar armour layout to the Spitfire, and was the toughest and most durable of the three. Serviceability rates of Hawker's fighter were always higher than the complex and advanced Spitfire. The Messerschmitt Bf 109 E-3 received extra armour in late 1939, and this was supplemented with a 10 mm thick armoured plate behind the pilot's head during and after the Battle of France. Behind the fuel tank, an 8 mm armoured plate was placed in the fuselage protecting the tank and the pilot from attacks from behind.

Propeller types

By July 1940, more efficient de Havilland and Rotol constant speed propellers had begun replacing two-pitch propellers on front line RAF fighters. The new units allowed the Merlin to perform more smoothly at all altitudes and reduced the takeoff and landing runs. The majority of the front line RAF fighters were equipped with these propellers by mid-August.[24] The Bf 109E also used a constant speed Vereinigte Deutsche Metallwerke (VDM) three-blade unit with automatic pitch control.

100 octane aviation fuel

As early as 1938 Roy Fedden, who designed most of the Bristol Engine Company's most successful aero engines, pressed for the introduction of 100 octane aviation fuel from the US, and later that year the British aero engine manufacturers Bristol and Rolls-Royce demonstrated variants of their 'Mercury' and 'Merlin' engines rated for 100 octane fuel.[27][28] A memorandum by the "Department of Defence Co-Ordination", 'Proposals for securing adequate supplies of 100 octane fuel to meet war requirements', 23 December 1938, noted that there was a need to increase supplies of 100 octane fuel and discussed ways in which this could be achieved.[29]

A meeting was held on 16 March 1939 to consider the question of when the 100 octane fuel should be introduced to general use for all RAF aircraft, and what squadrons, number and type, were to be supplied. The decision taken was that there would be an initial delivery to 16 fighter and two twin-engined bomber squadrons by September 1940.[30] However, this was based on a pre-war assumption that US supplies would be denied to Britain in wartime, which would limit the numbers of front-line units able to use the fuel.[31] On the outbreak of war this problem disappeared; production of the new fuel in the US, and in other parts of the world, increased more quickly than expected with the adoption of new refining techniques.[32] As a result, 100 octane fuel was able to be issued to all front-line Fighter Command aircraft starting in the spring of 1940.[33] [N 1]

Although U-boats and surface raiders had begun to take a heavy toll of tankers, in the summer of 1940 there was a surplus of these ships because of the incorporation into the British merchant marine of tanker fleets from countries overrun by Germany.[35] The combination of CS propellers and 100 octane fuel put the British fighters on par with the Luftwaffe.[30][36][37] Throughout 1940 the supply situation and distribution of the fuel to the front line services was discussed by the "Co-ordination of Oil Policy Committee".[38]

With 100 octane fuel the supercharger of the Merlin III engine could be "boosted" to +12 lbs/sq.in., producing 1,310 hp (977 kW) at 3,000 rpm at 9,000 feet (2,743 m) with a time limit of five minutes.[39] This increased power substantially improved the rate of climb, especially at low to medium altitudes, and increased the top speed by 25–34 mph up to 10,000 feet.[24][N 2] During the Battle of France and over Dunkirk RAF Hurricanes and Spitfires were able to use the emergency boost.[40][41] "In the first half of 1940 the RAF transferred all Hurricane and Spitfire squadrons to 100 octane fuel."[42]

In the opinion of a pre-war paper by the British Air Ministry, Germany, as a large producer of synthetic fuel, was thought to be in a favourable position to produce 100 octane fuel in large quantities.[43] The German supply of aviation fuels was largely based on the hydrogenation of coal, due to their limited supplies of natural crude oil. At the outbreak of the war, Germany already had seven destructive hydrogenation plants in operation, with a total installed capacity of 1,400,000 t/year of oil.[44]

At the start of the war the Luftwaffe standardized on 87 octane aviation gasoline, called "B4", made from leaded hydro-petrol extracted from brown coal.[45] In 1940 an improved fuel, designated "C2" was introduced having a higher aromatic content of 35–38% and giving performance equivalent to Allied 100 octane grade of that time.[45] C2 was used in small quantities by aircraft such as the Messerschmitt Bf 109E-4/N and E-7/N and the Messerschmitt Bf 110C when equipped with the DB 601N engine, that entered series production in October 1939.[46] The power was increased by 20% over that of the DB 601A, to 1,260 hp at 6,900 feet (2,100 m) at 1.35 atm boost pressure and 2,400 rpm.[46][47] By July, nine Bf 110 and three Bf 109 fighter Staffeln (squadrons) were equipped with the new engines,[47] By the end of October around 1,200 DB 601N engines had been delivered.[48] and the number of aircraft equipped with the improved engine gradually increased through the second half of the year.[49] However, due to leaking valves there was relatively high wear on the 601N-engines, which had a life of about 40 hours.[50][51]

Other fighter aircraft

In addition to the Hurricane, Spitfire, and the Bf 109, several other fighter aircraft — mostly twin-engined heavy fighters — took part in the Battle of Britain.

Messerschmitt Bf 110

At the start of the battle, the twin-engine Messerschmitt Bf 110 long range "destroyer" (German: Zerstörer) was expected to engage in air-to-air combat while escorting the Luftwaffe bomber fleet. Although the aircraft was well designed and the best of its class, being reasonably fast (Bf 110C-3 about 340 mph [547 km/h]) and possessing a respectable combat radius, the concept that the Bf 110 could defend bombers against a concerted attack by a force of fast single-seat, single-engined fighters was flawed. When pitted against the Hurricane and Spitfire the Bf 110s began to experience heavy losses through being only slightly more manoeuvrable than the bombers they were meant to escort and suffering from poor acceleration.[52]

A variant of the 110 was the Bf 110D-1, nicknamed "Dachshund-belly" (Dackelbauch) because of the fixed, wooden, 1,050 litre (277 U.S. gal) fuel tank fitted under the fuselage.[N 3] I./ZG 76, based in Norway, was equipped with this version in order to provide air cover for convoys sailing along the Norwegian coast. On 15 August, in the belief that all of the RAF fighter units were concentrated far to the south, Luftflotte 5 launched its first and only bomber attack against North Eastern England. Seven out of the 21 I.ZG 76 aircraft being used as bomber escorts were destroyed, including that of the Gruppenkommandeur ("Group Commander").[53]

The casualty rates for all of the Zerstörergeschwader wings using the Bf 110Cs were extremely high throughout the battle, and they were unable to fulfill the high aspirations of Hermann Göring, who had referred to them as his "Ironsides" (Eisenseiten)."[54]

The most successful role of the Bf 110 during the Battle was as a "fast bomber" (Schnellbomber), the same role that the Junkers Ju 88A had been designed for in the mid-1930s. One unit, Test Group 210" (Erprobungsgruppe 210) — originally meant to service test the Bf 110's intended (but ill-fated) replacement, the Messerschmitt Me 210 — proved it could carry a greater bomb load over a greater range than a Ju 87 and deliver it with similar accuracy, while its much higher maximum speed, especially at lower altitudes, meant it was far more capable of evading RAF fighters.[54][55]

The Bf 110 possessed a heavy armament of two 20 mm MG FF/M cannon and four 7.92 mm MG 17s concentrated in the forward fuselage, along with a single 7.92 mm MG 15 for rear defence in the rear cockpit.

Boulton Paul Defiant

For the British, the most disappointing fighter was the Boulton-Paul Defiant. This aircraft was intended to be used as a "bomber destroyer" because it was thought:

The speed of modern bombers is so great that it is only worthwhile to attack them under conditions which allow no relative motion between the fighter and its target. The fixed-gun fighter with guns firing ahead can only realise these conditions by attacking the bomber from dead astern...[56]

However, between the medium bomber types used by the Luftwaffe — the Do 17Z, the He 111P & H, and the Ju 88A, none of these had a manned tail-gunner's position in the rear fuselage as part of their designs, as used during the Battle.

By 1940, it was clear to both the RAF and the Luftwaffe that the deadliest opponents of bombers were single-engine, single-seat fighters with fixed, forward firing armament. Apart from the extra weight and drag imposed by the four-gun turret and second crew member, the Defiant lacked any directly forward-firing armament. Should the gunner need to escape from the turret in an emergency, the only way he could do this was to traverse the turret to one side and bail out through the escape hatch — but if the aircraft's electric system was disabled, immobilizing the all-electric turret due to its power source being knocked out, there was no escape. After the strong intervention of Dowding, who realised the Defiant was designed to an unworkable concept, there were only two units equipped with this aircraft, 141 and 264 squadrons. On 19 July, after encountering Bf 109s of III./JG 51, 141 Sqn had four Defiants shot down, one written off and one damaged, with 10 crew members killed or missing.[57] Just over a month later, on 24 August 264 Sqn suffered the loss of four Defiants shot down and three badly damaged with seven crew members killed.[58] Both units were withdrawn from 11 Group, reequipped, and took no further part in daytime operations.[59][60] However, the Defiant was found to be more effective as a night fighter. It equipped four squadrons and during the winter Blitz on London of 1940–41, Defiants shot down more enemy aircraft than any other type.[61]

Italian fighter aircraft

The Fiat CR.42 was a biplane fighter used by the Italian Air Corps (Corpo Aereo Italiano). They only made one mission during the battle itself when on 29 October they provided a bomber escort on a raid on Ramsgate.[62] Following the end of the battle, the Italian force continued to carry out limited raids on England, and on 11 November 1940, four CR.42s acting as escorts were destroyed by RAF Hurricanes with no loss to the RAF. German Luftwaffe aircraft had difficulty flying in formation with the biplanes, which also proved to be poor match for the more modern British fighters, and the CR.42s were transferred back to the Mediterranean theatre.[63]

The Italians also fielded a small number of Fiat G.50 monoplane fighters. Similar to the Luftwaffe's Bf 109E, this fighter was restricted by its short range of barely 400 miles (640 km), likely due to limited internal fuel, but unlike the German mainstay fighter, the lack of a radio unit in most participating aircraft also challenged its usability. It is not known for certain if an additional number of Macchi C.200 Saetta monoplane fighters escorting formations of Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero medium bombers ever participated in the Battle.

Other British fighters

The Bristol Blenheim was used by both Bomber and Fighter Commands. Some 200 Mk. I bombers were modified into Mk. IF long-range fighters with 600 (Auxiliary Air Force) Squadron based at Hendon, the first squadron to take delivery of these variants in September 1938. By 1939, at least seven squadrons were operating these twin-engined fighters and within a few months some 60 squadrons had transitioned to the type. The Mk. IF proved to be slower and less nimble than expected and by June 1940, daylight Blenheim losses were to cause concern for Fighter Command. It was then decided that the IF would be relegated mainly to night fighter duties where No. 23 Squadron RAF who had already operated the type under night time conditions had better success.

In the German night bombing raid on London, 18 June 1940, Blenheim night fighters accounted for five German bombers thus proving they were better suited in the nocturnal role. In July, No. 600 Squadron, by then based at RAF Manston, had some of its IFs equipped with Airborne Interception (AI) Mk. III radar. With this radar equipment, a Blenheim from the Fighter Interception Unit (FIU) at RAF Ford achieved the first success on the night of 2/3 July 1940, accounting for a Dornier Do 17 bomber. More successes came and, before long, the Blenheim was to prove invaluable in the night fighter role. Gradually, with the introduction of the Bristol Beaufighter in 1940–41, its role was supplanted by its faster, better armed progeny.[64]

The first Beaufighters entered service in early September 1940, at first delivered in standard day fighter camouflage schemes although the type was intended for a night fighting role. The first night operations took place in September and October 1940 and on the night of 19/20 November 1940, a Beaufighter IF, equipped with AI radar downed a Ju 88. The aircraft from 604 Squadron was flown by Flt Lt. John Cunningham, scoring the first of his 20 victories.[65]

The only British biplane fighter in operational service was the Gloster Gladiator which equipped No. 247 Squadron RAF, stationed in RAF Robourgh, Devon. Although no combat sorties took place at the height of the aerial battles, No. 247 Gladiators intercepted a He 111 in late October 1940, without result. No. 239 Squadron RAF using Gladiators in an army cooperation role and No. 804 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm outfitted with Sea Gladiators were also operational during the Battle of Britain.[66]

The British had a cannon-armed fighter coming into service, the twin-engined Westland Whirlwind, but problems with its engines and slow production meant it did not enter service until December 1940.

Bomber aircraft

The majority of the bomber aircraft involved in the Battle of Britain were German although the Italians fielded a small number.

German bomber aircraft

The Luftwaffe in 1940 primarily relied on three twin-engined medium bombers: the Dornier Do 17, the Heinkel He 111 and the Junkers Ju 88. Despite the Luftwaffe being in the possession of advanced gyroscopic bomb sights, the Lotfernrohr 7 for daylight bombing and electronic navigational aids like the Knickebein, X-Gerät and Y-Gerät for nocturnal bombing, there were some very fundamental limitations to the accuracy of bombing from level flight, and there was no guarantee that such attacks could achieve success on small or difficult targets such as radar stations.[67]

For precision attack emphasis was placed on the development of aircraft which could utilise the technique of dive bombing for which the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka was specifically designed. The Junkers Ju 88 was fitted with external dive brakes and a control system, similar to those of the Ju 87 and could carry out a dive bombing role, although it was primarily used as a level bomber. The light bomb loads carried by the Ju 87 had been used to great effect during the Battle of France. However, the Ju 87 was slow and possessed an inadequate degree of defensive weaponry, with only a single, 7.92mm calibre MG 15 machine gun at the rear of the cockpit for rearward defense. Furthermore, it could not be effectively protected by fighters, because of its low speed and the very low altitudes at which it ended its dive bomb attacks. The Stuka depended on air superiority, the very thing being contested over Britain. It was therefore withdrawn from attacks on Britain in August after prohibitive losses, leaving the Luftwaffe short of precision ground-attack aircraft.[67]

Another constraint was imposed by the light armament carried by the Luftwaffe bombers. At the start of the battle they were still armed with an average of three hand held MG 15 light machine guns, which were supplied by 75 round "saddle drum" magazines. When faced with concentrated attacks by modern fighters such as the Hurricane and Spitfire this proved totally inadequate. Although many of the Luftwaffe gunners were well trained and capable of hitting a fast moving fighter the damage done was seldom enough to stop the attack in time to prevent heavy damage being done to the bomber. The high rate of fire of the MG 15 meant that the small magazines emptied quickly; the time taken to reload often gave a fighter the time it needed to make a successful attack. Efforts had been made to increase the number of defensive weapons, but this also meant that because the weapons were hand-held either more crew members were needed in each aircraft, or the existing crew members could be overworked. It was a problem which was never to be fully resolved and the Luftwaffe bombers had to rely on the ability of their fighters to protect their formations.[67]

The bombers did enjoy some advantages. As more armour plate was added in vital areas, crew members became less vulnerable. Their fuel tanks were also well protected by layers of self-sealing rubber, although the incendiary and tracer ammunition which was carried by RAF fighters could sometimes ignite fuel vapour in empty tanks.

The He 111 was nearly 100 mph slower than the Spitfire and didn't present much of a challenge to catch, although the heavy armour for the crew stations, self-sealing fuel tanks and progressively uprated defensive armament meant that it was still a challenge to shoot down. It was the most numerous German bomber type during the Battle, and was capable of delivering 2000 kg of bombs to the target, carried in an internal bomb bay – usually eight 250 kg bombs, stored vertically. Subsequent variants allowed further increase in the bomb load and the maximum size of bombs carried, with external bomb racks. The state-of-the art Lotfernrohr 7 gyroscoping bomb sight fitted to the Heinkel allowed for reasonable accuracy, for a level bomber. The main versions of the He 111 in use were the Jumo engined H-1, H-2 and H-3 and the DB 601 powered P-2 and P-4. Small numbers of the aircraft, called H-1x and H-3x, were equipped with Knickebein and X-Gerät and were used by Kampfgruppe 100 (KGr. 100) at night during the closing stages of the battle. Y-Gerät equipped H-5y of III. Gruppe Kampfgeschwader 26 began to take part in the Blitz of the winter of 1940–1941.[68]

The Do 17Z was an older type of German bomber that was no longer in production by the start of the Battle. Still, many Kampfgeschwadern still operated the Dornier, known as "the flying pencil" due to its sleek fuselage. Its air-cooled radial BMW engines meant that many of these aircraft were able to survive fighter attack because there was no vulnerable cooling system to disable.[69] The Dornier was also manoeuvrable, and as a result was popular in the Luftwaffe. The main problem with the Dornier was its limited 200 mile combat range, when fully loaded with bombs. Its bomb carrying capacity was also limited to 2,205 lbs.[70] Older versions of the Do 17, mainly the E-1, were still used for weather reconnaissance duties.

Of the four types of bomber used by the Luftwaffe the Ju 88 (the original Schnellbomber) was considered to be the most difficult to shoot down. As a bomber it was relatively manoeuvrable and, especially at low altitudes with no bomb load, it was fast enough to ensure that a Spitfire engaged in a tail-chase would be hard pressed to catch up. It could carry up to 3,000 kg of bombs. However, only small sized 50 and 70 kg bombs, up to a total weight of 1,400 kg, could be carried internally, while larger bombs had to be carried on external racks, causing considerable drag. The Ju 88 was also extremely versatile, being fitted with both the Lotfernrohr 7 gyroscopic bomb sight and Stuvi dive sight as well as retractable dive brakes. The front MG 15 machine gun could be locked with an ingenious retracting clamp just forward of the windscreen to lock it for forwards firing, and could be used for strafing runs. Thus the Ju 88, dubbed as the "Big Stuka", was equally at home when it came to level or dive bombing or low-level attacks. The versions of the Ju 88 used during the battle were the small-wingtipped A-1 and the A-5; the latter incorporated several improvements, including the A-4's increased 20.08 meter wingspan and uprated armament.[71] The Ju 88 C-1 heavy fighter version, with a sheet metal nose replacing the bombers' "beetle's-eye" faceted glazing, was also used in small numbers.

In reality, the Ju 88, although operating in smaller numbers than the Do 17 and He 111, suffered the highest losses of the three German bomber types. Losses of Do 17 and He 111s amounted to 132 and 252 machines destroyed respectively, while 313 Ju 88s were lost.[72][73]

I./KG 40 was equipped with a small number of the four-engined Focke-Wulf Fw 200 converted airliners, which were used to attack shipping and to provide long-range reconnaissance around the British Isles and out into the Atlantic Ocean.[74]

Italian bomber aircraft

The Corpo Aereo Italiano (CAI) was an expeditionary force of the Regia Aeronautica that participated in the very late stages of the Battle of Britain.

The bomber element consisted of some 70 Fiat BR.20 twin engined bombers of 13° Stormo and 43° Stormo. based in Belgium. The Italian BR.20 was a bomber capable of carrying 1600 kg (3,528 lb) of bombs.

Supporting aircraft included five CANT Z.1007 used for reconnaissance duties and several Caproni Ca.133 transports. The Italian bomber force flew limited operations, undertaken towards the end of the battle. The CAI's bombers flew about 102 sorties, only one of which attained any notable success— severe damage being caused to a canning factory in Lowestoft by a raid on 29 November 1940, which killed three people.[75]

The first mission on 25 October,[62] a night attack of 16 aircraft on Harwich led to three bombers being lost, with one crashing on takeoff and two becoming lost on their return. On 11 November a formation of 10 BR.20s escorted by Fiat CR.42 biplane fighters on a daylight raid on Harwich, was intercepted by RAF Hurricanes. Three bombers were downed and three CR.42s destroyed with four damaged, with no loss to the Hurricanes.[63] In early January 1941 all of the bombers were redeployed.

Full list of aircraft

United Kingdom

Only the squadrons listed as Battle of Britain RAF squadrons were counted as being part of the Battle of Britain for the award of a campaign medal

- Bristol Blenheim

- Blenheim Mk. IF – Fighter Command (night fighter)

- Blenheim Mk IVF – Coastal Command

- Bristol Beaufighter Mk. I – Fighter Command

- Boulton Paul Defiant Mk. I – Fighter Command

- Gloster Gladiator – Fighter Command (limited numbers)

- also Gloster Sea Gladiator (limited numbers, operated by 804 Naval Air Squadron)

- Hawker Hurricane Mk. I and Mk IIA series I – Fighter Command

- Supermarine Spitfire Mk. I and Mk. II – Fighter Command

- Westland Lysander (limited numbers) (Opening days)

- Grumman Martlet Mk. I (limited numbers, operated by 804 Naval Air Squadron late in battle)

- Fairey Fulmar (limited numbers, operated by 808 Naval Air Squadron)

Germany

- Breguet 521 Bizerte

- Dornier Do 17

- Do 17M-1

- Do 17P-1

- Do 17Z-2

- Do 17Z-3

- Dornier Do 18D-1 (Air-Sea rescue)

- Focke-Wulf Fw 200C-3

- Heinkel He 59C-2 (Air-Sea rescue)

- Heinkel He 111

- He 111H-1

- He 111H-2

- He 111H-3

- He 111P-2

- He 111P-4

- Heinkel He 115 B-1 (Air-Sea rescue)

- Heinkel He 115 B-2 (Air-Sea rescue)

- Junkers Ju 87

- Ju 87B-1

- Ju 87B-2

- Junkers Ju 88

- Ju 88A-1

- Ju 88A-5

- Messerschmitt Bf 109

- Bf 109E-1

- Bf 109E-1B

- Bf 109E-3

- Bf 109E-4

- Bf 109E-4/B

- Bf 109E-4/N

- Bf 109E-4/BN

- Bf 109E-7

- Bf 109E-7/N

- Bf 109F-1

- Messerschmitt Bf 110

- Bf 110C-4

- Bf 110C-4/B

- Bf 110C-5

See also

References

Notes

- In September 1939, Bristol Blenheim Mk IVs of several squadrons of Bomber Command (18, 21, 57, 82, 90, 101, 107, 110, 114 and 139 Squadrons) were being converted to use Bristol Mercury XVs, and to carry additional fuel tanks for 100 octane fuel in their outer wings. This work was completed by 7 October.[34]

- If the pilot resorted to emergency boost, he had to report this on landing and it had to be noted in the engine log book.

- It was intended that this tank could be jettisoned when empty or when threatened with fighter attack. In practice the mechanism usually failed to work.

Citations

- Hurricane R4118 Archived 14 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 25 February 2014

- Bungay 2000, p. 388.

- "Retrieved: 7 February 2016". Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Price 2002, p. 78.

- Bungay 2000, p. 74.

- Delve 2007, p. 24.

- Air Ministry 1940/1972, p. 18, Section 11 (II).

- Bungay 2000, p. 78.

- Green 1980, p. 70.

- Brown, Eric (1977–1978). Wings of the Luftwaffe. UK: Pilot Press, Ltd. pp. 151 & 155. ISBN 0-385-13521-1.

- McKinstry 2007, p. 205.

- Baubeschreibung für das Flugzeugmuster Messerschmitt Me 109 mit DB 601, 1939. Reprint: Luftfahrt-Archiv Hafner.

- Radinger and Schick 1999.

- Bungay 2000, p. 199.

- Bungay 2000, p. 176.

- Price 1980, pp. 22, 41, 156.

- Price 1996, pp. 20–21, 53.

- Price 1982, p. 76.

- Price 1980, pp. 132–133, photo section between pp. 150–151.

- Williams and Gustin 2003, p. 23.

- Williams and Gustin 2003, p. 313.

- Bungay 2000, p. 197.

- Bungay 2000

- Price 1996, pp. 18–21.

- Wagner, Ray; Nowarra, Heinz (1971). German Combat Planes: A Comprehensive Survey and History of the Development of German Military Aircraft from 1914 to 1945. New York City: Doubleday & Company. p. 229.

- Wagner, Ray; Nowarra, Heinz (1971). German Combat Planes: A Comprehensive Survey and History of the Development of German Military Aircraft from 1914 to 1945. New York City: Doubleday & Company. p. 235.

- Warner 2005, pp. 99, 112.

- Flight 1938, p. 528.

- "Proposals for securing adequate supplies of 100 octane fuel to meet war requirements." Archived 12 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine naa12.naa.gov.au. Retrieved: 2 January 2010.

- Morgan and Shacklady 2000, pp. 55–56.

- Peyton-Smith 1971, p. 259.

- Payton-Smith 1971, pp. 259–260.

- Price 1996, p. 19.

- Warner 2005, p. 135.

- Payton-Smith 1971, pp. 128–130.

- Society of Automotive Engineers 1997, p. 11.

- Wood and Dempster 1990, p. 87.

- "10/282 Minutes of Oil Policy Committee meetings." Archived 11 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine National Archives AVIA. Retrieved: 15 June 2009.

- Harvey-Bailey 1995, p. 155.

- Beamont 1989, p. 30.

- Gray 1990, p. 27.

- Lloyd, p.139

- "Proposals for securing adequate supplies of 100 octane fuel to meet war requirements." Annex 1, p. 8. Archived 12 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved: 7 April 2012

- Report on the Petroleum and Synthetic Oil Industry of Germany. London: The Ministry of Fuel and Power, 1947. p. 47.

- Archived Fischer-Tropsch.org pdf file (extract) pp.119–120. Retrieved:27 March 2019.

- Griehl 1999, p. 8.

- Mankau and Petrick 2001, p. 24.

- Mankau and Petrick 2001, p. 28.

- Mankau and Petrick 2001, pp. 24–29.

- Starr 2005, pp. 43–47.

- van Ishoven 1977, p. 107.

- Bungay 2000, pp. 52–53.

- Weal 1999, p. 48.

- Weal 1999, pp. 42–51.

- Bungay 2000, pp. 257–258.

- Air Staff memorandum, June 1938, Quoted in Bungay 2000, p. 84.

- Ramsay 1989, pp. 326–327.

- Ramsay 1989, pp. 376–377.

- Bungay 2000, pp. 84, 178, 269–273.

- Ansell 2005, pp. 712–714.

- Taylor 1969, p. 326.

- Wood and Dempster 1969, p. 299.

- Green and Swanborough 1982, p. 308.

- Rimell 1990, p. 23.

- Rimell 1990, p. 17.

- Rimell 1990, p. 27.

- Bungay 2000, pp. 251–257"

- Ramsay 1988, pp. 25–27.

- Price 1980, pp. 7–8.

- Goss 2005, p. 12.

- Filley 1988, pp. 10–19.

- "Aircraft Strength and Losses." tripod.com. Retrieved: 2 January 2010.

- "Aircraft Strength and Losses in WW II" (Information based on Cooksley, Peter Battle of Britain, 1990). Archived 4 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Patriot Files. Retrieved: 17 October 2011.

- Ramsay 1989, pp. 605, 655, 680, 693.

- Harvey 2003, p. 607.

- Green and Swanborough 1982, pp. 311–312.

Bibliography

- Ansell, Mark. Boulton Paul Defiant: Technical Details and History of the Famous British Night Fighter. Redbourn, Herts, UK: Mushroom Model Publications, 2005, pp. 712–714. ISBN 83-89450-19-4.

- Beamont, Roland. My Part of the Sky. London: Patrick Stephens, 1989. ISBN 1-85260-079-9

- Bungay, Stephen. The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain. London: Aurum Press 2000. ISBN 1-85410-721-6 (hardcover), ISBN 1-85410-801-8 (paperback 2002).

- Cooper, Matthew. The German Air Force 1933–1945: An Anatomy of Failure. New York: Jane's Publishing Incorporated, 1981. ISBN 0-531-03733-9.

- Delve, Ken. The Story of the Spitfire: An Operational and Combat History. London: Greenhill books, 2007. ISBN 978-1-85367-725-0.

- Feist, Uwe. The Fighting Me 109. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1993. ISBN 1-85409-209-X.

- Filley, Brian. Junkers Ju 88 in action: Part 1. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1988. ISBN 0-89747-201-2.

- Foreman, John. Battle of Britain: The Forgotten Months, November And December 1940. Wythenshawe, Lancashire, UK: Crécy Publishing, 1989. ISBN 1-871187-02-8.

- Goss, Chris. Dornier 17 (In Focus). Surrey, UK: Red Kite Books, 2005. ISBN 0-9546201-4-3.

- Gray, Colin. Spitfire Patrol. London: Hutchinson, 1990. ISBN 1-86941-083-1.

- Halpenny, Bruce Barrymore. Fight for the Sky: Stories of Wartime Fighter Pilots. Cambridge, UK: Patrick Stephens, 1986. ISBN 0-85059-749-8.

- Green, William. Messerschmitt Bf 109: The Augsburg Eagle; A Documentary History. London: Macdonald and Jane's Publishing Group Ltd., 1980. ISBN 0-7106-0005-4.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough, eds. "Fiat BR.20... Stork à la mode". Air International Volume 22, No. 6, June 1982, pp. 290–294, 307–312. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Griehl, Manfred. Messerschmitt Bf 109F (Flugzeug Profile 28) (in German with captions in German/English). Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-7643-0912-9.

- Halpenny, Bruce Barrymore. Fighter Pilots in World War II: True Stories of Frontline Air Combat . Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Books Ltd, 2004. ISBN 1-84415-065-8 (paperback).

- Halpenny, Bruce Barrymore. Action Stations: Military Airfields of Greater London v. 8 (hardcover). Cambridge, UK: Patrick Stephens, 1984. ISBN 0-85039-885-1.

- Harvey-Bailey, A. The Merlin in Perspective: The Combat Years. Derby, UK: Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, 1995 (4th edition). ISBN 1-872922-06-6.

- Harvey, A. Collision of Empires: Britain in Three World Wars, 1793–1945 London: Hambledon Continuum, 2003. ISBN 978-1-85285-078-4

- History of Aircraft Lubricants. SAE International, Society of Automotive Engineers, 1997. ISBN 0-7680-0000-9.

- Holmes, Tony. Spitfire vs Bf 109: Battle of Britain. Oxford, London: Osprey Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84603-190-8.

- Hooton, E.R. Luftwaffe at War: Blitzkrieg in the West, Vol. 2, London: Chevron/Ian Allan, 2007. ISBN 978-1-85780-272-6.

- Lloyd, Sir Ian and Pugh, Peter., Hives and the Merlin. Cambridge : Icon Books, 2004. ISBN 1840466448.

- Mankau, Heinz and Peter Petrick. Messerschmitt Bf 110, Me 210, Me 410. Raumfahrt, Germany: Aviatic Verlag, 2001. ISBN 3-925505-62-8.

- Morgan, Eric B. and Edward Shacklady. Spitfire: The History. Stamford, UK: Key Books Ltd, 2000. ISBN 0-946219-48-6.

- Olson, Lynne and Stanley Cloud. A Question of Honor. The Kosciuszko Squadron: Forgotten Heroes of World War II. New York: Knopf, 2003. ISBN 0-375-41197-6.

- Overy, Richard. The Battle of Britain: The Myth and the Reality. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001 (hardcover, ISBN 0-393-02008-8); 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-393-32297-1).

- Payton-Smith, D J. Oil: A Study of War-time Policy and Administration. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1971. (no ISBN) SBN 1-1630074-4

- Price, Alfred. The Hardest Day: 18 August 1940. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1980. ISBN 0-684-16503-1.

- Price, Alfred. Spitfire Mark I/II Aces 1939–41 (Aircraft of the Aces 12). London: Osprey Books, 1996, ISBN 1-85532-627-2.

- Price, Alfred. The Spitfire Story. London: Jane's Publishing Company Ltd., 1982. ISBN 0-86720-624-1.

- Price, Alfred. The Spitfire Story: Revised second edition. Enderby, Leicester, UK: Siverdale Books, 2002.

- Prien, Jochen and Peter Rodeike.Messerschmitt Bf 109 F,G, and K: An Illustrated Study. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 1995. ISBN 0-88740-424-3.

- Quill, Jeffrey. Spitfire: A Test Pilot's Story. London: John Murray (Publishers) Ltd, 1993. ISBN 0-7195-3977-3.

- Ramsay, Winston, ed. The Blitz Then and Now, Volume 2. London: Battle of Britain Prints International Ltd, 1988. ISBN 0-900913-54-1.

- Ramsay, Winston, ed. The Battle of Britain Then and Now, Mk V. London: Battle of Britain Prints International Ltd, 1989. ISBN 0-900913-46-0.

- Rimell, Ray. Battle of Britain Aircraft. Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, UK: Argus Books, 1990. ISBN 1-85486-014-3.

- Scutts, Jerry. Messerschmitt Bf 109: The Operational Record. Sarasota, Florida: Crestline Publishers, 1996. ISBN 978-0-7603-0262-0.

- "Some Trends in engine design (article and photos)." Flight No. 1563, Volume XXXIV, 8 December 1938.

- Starr, Chris. "Developing Power: Daimler-Benz and the Messerschmitt Bf 109." Aeroplane magazine, Volume 33, No. 5, Issue No. 385, May 2005. London: IPC Media Ltd.

- Taylor, A.J.P. and S.L. Mayer, eds. A History Of World War Two. London: Octopus Books, 1974. ISBN 0-7064-0399-1.

- Taylor, John W. R. "Boulton Paul Defiant." Combat Aircraft of the World from 1909 to the present. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. ISBN 0-425-03633-2.

- Warner, G. The Bristol Blenheim: A Complete History. London: Crécy Publishing, 2nd edition 2005. ISBN 0-85979-101-7.

- Weal, John. Messerschmitt Bf 110 'Zerstōrer' (Aces of World War 2). Botley, Oxford UK: Osprey Publishing, 1999. ISBN 1-85532-753-8.

- Williams, Anthony G. and Dr. Emmanuel Gustin. Flying Guns: World War II. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-84037-227-3.

- Wood, Derek and Derek Dempster. The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain and the Rise of Air Power. London: Arrow Books, second revised illustrated edition, 1969. ISBN 978-0-09-002160-4.

- Wood, Derek and Derek Dempster. The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain and the Rise of Air Power. London: Tri-Service Press, third revised edition, 1990. ISBN 1-85488-027-6.

External links

- Royal Air Force history

- Battle Of Britain Historical Society

- Battle of Britain in the Words of Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding (despatch to the Secretary of State, August 1941)

- Map of UK Airfields and squadrons.

- RAF Battle of Britain Roll of Honour

- Battle-Of-Britain Website in Dutch.

- Battle of Britain Memorial

- Shoreham Aircraft Museum

- Tangmere Military Aviation Museum

- Kent Battle of Britain Museum

- Battle of Britain from the German perspective (Lt Col Earle Lund, USAF): Pdf file

- Battle of Britain from the German perspective (Lt Col Earle Lund, USAF)

- YouTube Video on the subject of the "Messerschmitt Bf 109, Why Such Short Range?"